ABSTRACT

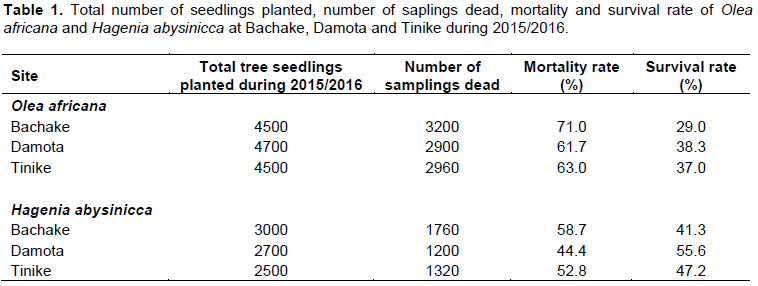

The study was conducted to explore the growth and survival rate of the native tree species of Ethiopia, Olea africana and Hagenia abysinicca in Lake Haramaya Watershed, Eastern Ethiopia. Three sub watersheds of Lake Haramaya Watershed, namely, Bachake, Damota, and Tinike were selected purposefully on the basis of their extreme degradation and nearby vanished Lake Haramaya. In each sub watersheds, a total of about 12 main standard quadrats have been applied and the required data has been recorded. The result of the study indicated that O. africana performs well at Damota sub watershed, accounting 38% of survival rate followed by Tinike sub watershed having a survival rate of 37%. Only 29% of the total planted O. africana were survived at Bachake sub watershed. Furthermore, it has been revealed via this study that about 55.6% of H. abysinicca survived at Damota sub watershed. Comparing the survival rate of the two species, H. abysinicca better withstand and grow under an extreme pressure of local peoples intervention at all sub watersheds. Therefore, the study shows that growing and maintaining of these two endemic trees in all sub watersheds were difficult task unless much awareness will be made. Lastly, the study encourages mega projects on growth and survival rate of other native trees species and explores the challenges associated with growing these trees in the study area in specific and in Ethiopia in general.

Key words: Survival rate, endemic trees, sub watershed.

Ethiopia is very known by its heterogeneous higher plant species estimated to be around 6500 to 7000, of which more than 12 to 19% are native (WCMC, 1992; Teketay, 2001; Hurni, 2007; CBD, 2008). This is due to the fact that the country has a wide variety of ecological characteristics associated with ample diversity of plant and animal species (Alemayehu, 2002). However, a number of studies indicated that almost all of the natural vegetation of Ethiopia is under an extreme pressure of an thropogenic threats (Yirdaw, 1996; Million, 2001; Tesfaye et al., 2015; Newton and Cantarello, 2015). Given about 85% of the population Ethiopia is living in the rural areas, their livelihood system is either directly or indirectly depended on agriculture, which provides about 52% of the country’s GDP (World Bank, 2000; CIA, 2001).

The speedy decline of forest resources in Ethiopia has resulted in reduction of their biodiversity and on the verge of extinction of certain tree species (Tekle and Hedlund, 2000; WRI, 2001; Alemayehu, 2002a). Olea africana and Hagenia abysinicca are the major endemic tree species mainly found in Ethiopia, basically on the highland areas of the country. Currently, these tree species are under a big threat of human influences. The local name of O. africana is Ejersa in Afan Oromo and Weyira in Amharic. This species is well known by the local people for its traditional medicine preparation, tooth brush and sometimes for charcoal production. Moreover, Hagenia abysinicca is locally known as Muka Heexoo in Afan Oromo and Yekoso Zaf in Amharic and well known for its medicinal value.

The climate of Ethiopia has been changing as a result of global and local effects of vegetation degradation. Loss of forest cover and biodiversity owing to human-induced activities is a growing arena of many parts of the world including our country, Ethiopia (Demissew, 1980). Thus, frequent drought, crop failure and famine are becoming common events in the highlands, like eastern Hararghe which are the symbols of desertification (Demel, 2001).

In line with this, Haramaya University, Ethiopia via Lake Haramaya Watershed project has given deep attention to these endemic trees and grows the seedlings to use them as a main rehabilitation tree of the degraded lands of Lake Haramaya sub watersheds. This is for the sake of maintaining the species into the environment, though it was a challenging task. Therefore, this study was undertaken to explore the growth and survival rate of the endemic tree species of O. africana and H. abysinicca, so as to put baseline information about the status of the two tree species in the watershed.

Description of the study area

Lake Haramaya Watershed is located in Haramaya and partly in Kombolcha districts, Eastern Hararghe Zone, Oromia National Region State, and East Ethiopia. The Watershed lies between 9°23´12.27´´- 9°31´9.85´´ N and 41°58´28.02´´- 42°8´h10.26´´ E (UTM Zone 38) (Figure 1) and covers an area of 15,329.96 ha. The elevation ranges from 1800 to 2345 m above sea level.

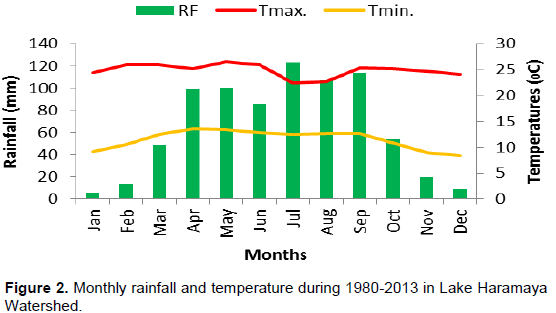

Information obtained from Ethiopian National Meteorology Agency indicates that the mean annual rainfall and mean maximum and minimum temperatures of Haramaya watershed are 847.9 mm, 24.7°C, and 11.5°C, respectively. The area received bimodal pattern of rainfall (Figure 2).

This study was conducted in particular at Bachake (3 ha), Damota (2.75 ha) and Tinike (3 ha) sub-watersheds, which are among the 28 sub watersheds of Lake Haramaya watershed. The reason for choosing the three of the sub-watersheds were due to their presence under the extreme pressure of anthropogenic factors; local communities were using these lands as a common grazing lands, expansion of agriculture to plant cash crops like Khat (Catha edulis) and to lesser extent coffee (Coffee arabica). Generally, many socio-economic activities were well notified as per the preliminary field observation of this study and key informant informal interview (not presented in this paper). Furthermore, of the 28 sub-watersheds, three of them are very nearby vanished Lake Haramaya, (on average 5 km away from the lake).

Seedlings preparation techniques

Seedling preparation has been conducted at Rare Nursery site, Haramaya University, Ethiopia. In the processes of seedlings preparation, forest soil, compost /farm yard manure, sand, and local top soil were used by mixing all the substrates at different ratios. The most used ratio is 3 local top soils: 2 forest soil/compost/farm yard manure: 1 sand (Figure 3). The mixed up media were added into a pot having a diameter size of 8 cm to support the sown seeds. Most potting mixes were soilless to avoid soil borne diseases and promote good drainage and suitable environment with sufficient water-holding capacity, nutrient content, and aeration for plant growth and development. Therefore, the pot-planted seedlings stayed on nursery site for at least six months begging from their planting time and all the required management were undertaken till plantation time. Then after, the seedlings of both O. africana and H. abysinicca were taken to the field via tractor-vehicle used for transportation of seedlings. The height of O. africana at the time of planting was estimated to be 35 cm and that of H. abysinicca was estimated to be about 45 cm, just the height above the ground.

Site preparation techniques for plantation

All the selected sub watersheds have been delineated and to lesser extent area closure has been done accordingly, though not effective. Additionally, physical soil and water conservation structures have been built by the local people with the coordination of Lake Haramaya Watershed Project, early before the main rainy season of Ethiopia (June, July, August, and September). The work of constructing the physical structure was better in Damota sub watershed. Finally, pits having an average depth of 30 cm and width of 40 cm were prepared along the physical structures across the slope within 2 m distance from one another. Majority of the pits were prepared by the respective farmers of the sub watersheds and seedlings plantation campaign was made by the local people in collaboration with Lake Haramaya Watershed Project run under Haramaya University.

Transect establishment, data collection and analysis

For each specific study site (Bachake, Damota, and Tinike), four subplots has been established systematically across the slope, one with its center located at the center of the spoke and the remaining three located at 20.5 m away from the center subplots (Figure 4). Each subplot has a 7.5 m radius. The operation has been multiplied 12 times with same transects size and design for all specific study sites at an interval of 50 m. Therefore, a total of about 12 main quadrats have been laid out for each sub watersheds and the required data has been recorded (Figure 5). Mortality rate and survival rate were calculated for both endemic tree species at all sub watersheds in the study area. The formulas used were (Megan, 2013):

Survival rate = 100 – Mortality rate

The results of the study depicted that of the transects established at all sub watersheds, O. africana performs well at Damota, accounting about 38% of survival rate, followed by Tinike sub watershed having a survival rate of 37%. However, at Bachake sub watershed little survival rate of O. africana has been recorded, only 29% (Table 1). The reasons for the variation of survival rate at all sub watersheds were due to high interference of local peoples. However, some studies are indicating that conservation and management of plants dominated by farming communities are getting attention nowadays (Garrity and Verchot, 2008; Lemenih and Kassa, 2014). Furthermore, it has been noticed during the study that the perception of local people in all sub watersheds, particularly, in Bachake sub watersheds, towards the growth of considered endemic tree species was so poor though they use these trees for traditional and other purposes (Table 2). Rather, they need to use the lands for free grazing.

Thus, of the total number of seedlings planted during 2015/2016 rainfall season, majority of them have died. Late plantation due to late onset of rainfall and early cessation, poor ways of plantation, little commitment by local people in monitoring after plantation, farmer’s preferences of other commercial trees like, Eucalyptus species, Grevillea robust and fruit trees are also another factor. Soil as a factor of seedlings growth has been kept constant in this particular work. The other negligible challenges of seedlings plantation in this work was those seedlings that died or at risk while transportation for plantation. The aforementioned constraints are similar to those facing the forest development in Ethiopia as noted by Derero et al. (2011) which include: transportation of seedlings, poor seedling quality and inappropriate silviculture, poor research extension linkage and poor coordination in the sector.

On the other hand, the study indicated that of the total H. abysinicca planted 3000 seedlings during 2015 rainfall season, about 41% survived at Bachake sub watershed, whereas it was 55.6 and 47.2% for Damota and Tinike sub watersheds, respectively. Comparing the two tree endemic species, H. abysinicca performed well at all sub watersheds. This could be due the reason that H. abysinicca has a natural ability to withstand and grow under an extreme pressure of human influence. Furthermore, Negash et al. (2012) and Tadesse et al. (2014) suggested that it may be the result of socio-culture, land use and management intensities, and farmers’ perceptions on the specified tree in the area that leads the allowance of trees to grow.

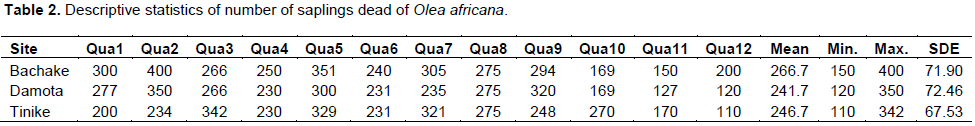

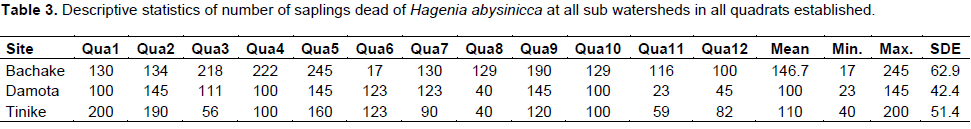

Furthermore, Table 2 shows a simple descriptive statistics of number of saplings dead for O. africana at all sub watersheds considered for this study. In all quadrats established at all sub watersheds, Bachake sub watershed shows the highest number of samplings dead, about 400 plants. However, the study revealed that the average value for samplings dead at Damota sub watershed was estimated to be lower than the other two sub watersheds, accounting for about 241.7 samplings of the planted 4700 (Table 2). The same pattern has been noticed for H. abysinicca where the average samplings dead at Damota sub watershed were less, about 100 samplings followed by Tinike sub watershed which is about 110 samplings (Table 3). The reason for this could be due to a bit commitment of the local people towards the management of the respective sub watersheds.

It has been recognized via this study that of planted samplings of O. africana 13700 at all sub watersheds considered in this paper, about 9060 have already died due to many reasons in the areas (Table 4). The average value of dead samplings of O. africana at all sub watersheds has been estimated to be 3020 (Table 4).

Moreover, of the total of the planted samplings at all sub watersheds of H. abysinicca 8200, about 4280 samplings were dead. The dead samplings at all sub watersheds considered ranges from 1200 to 1760 to have the mean value of 1427 samplings (Table 5).

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

It could be generalized from the results of the study that the growth and survival of endemic tree species, O. africana and H. abysinicca have been widely intervened by the human activities at all sub watersheds. Of three sub watersheds, both trees perform well at Damota, survival about 38 and 55.6% for O. africana and H. abysinicca, respectively. In contrast, little survival rate for both tree species have been observed at Bachake sub watershed. In line with this, much has to be done on the local communities’ awareness creation about the importance of these endemic trees. Training and participatory nursery developments are proven methods of building farmers awareness, leadership and technical skills (Carandang et al., 2006). Efforts by Haramaya University via Lake Haramaya Watershed project to rehabilitate these degraded watershed using endemic trees has been done, however, little attention has been given by Woreda administrative. Therefore, the study encourages strong linkage between the Woreda administrative and University, one to rehabilitate the degraded watersheds, two to maintain such an endemic tree species with the watershed in specific and with the country in general.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Alemayehu M (2002). Forage Production in Ethiopia: A case study with implications for livestock production. Ethiopian Society of Animal Production (ESAP), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

|

|

|

|

Alemayehu W (2002a). Opportunities, constraints and prospects of the Ethiopian Orthodex Tewahido Churches in south Gondar, northern Ethiopia. MSc. Thesis: Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences;

|

|

|

|

|

Carandang WM, Tolentino EL, Roshetko JM (2006). Smallholder Tree Nursery Operations in Southern Philippines – Supporting Mechanisms for Timber Tree Domestication. International Tree Crops Journal (in press).

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) (2001). CIA, the World Factbook, Ethiopia. http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications /factbook/geos/et.html.

|

|

|

|

|

Convention on Biological Diversity CBD News (CBD) (2008). forest and aquatic plants genetic resources. Addis Ababa: Institute of biodiversity conservation.

|

|

|

|

|

Derero A, Gailing O, Finkeldey R (2011). Maintenance of genetic diversity in Cordia africana Lam.,a declining forest tree species in Ethiopia. Tree Genet. Genomes 7:1-9.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Demel T (2001). Deforestation, Wood Famine, and Environmental Degradation in Ethiopia's Highland Ecosystems: Urgent Need for Action. Forest Stewardship Council (FSC Africa), Kusami, Ghana. Northeast Afr. Stud. 8:53-76.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Demissew S (1980). A study on the structure of a montane forest. The Menagesha-Suba State Forest. Unpublished M.Sc Thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa.

|

|

|

|

|

Garrity D, Verchot L (2008). Meeting challenges of climate change and poverty through agroforestry. World Agroforestry Centre, Nairobi.

|

|

|

|

|

Hurni H (2007). Challenges for sustainable rural development in Ethiopia. Faculty of Technology, Addis Abeba University, Addis Abeba.

|

|

|

|

|

Lemenih M, Kassa H (2014). Re-greening Ethiopia: history, challenges and lessons. Forests 5:1896-1909.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Megan K (2013). Assessing the Plant Species, Mortality Rates and Water Availability under the Canopies in the MillionTreesNYC Plots.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Million B (2001). Forestry outlook study in Africa. Regional, sub Regional and Countries Report, opportunities and challenges towards 2020; FAO forestry paper No. 141. Synthesis Africa Forests View to 2020. Rome, Italy.

|

|

|

|

|

Newton AC, Cantarello E (2015). Restoration of forest resilience: an achievable goal? – New For. 46:645-668.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Negash M, Yirdaw E, Luukkanen O (2012). Potential of endemicmultistrata agroforests for maintaining native floristic diversity in the south-eastern Rift Valley escarpment, Ethiopia. Agrofor. Syst. 85:9-28.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Schulz BK, Bechtold WA, Zarnoch SJ (2009). Sampling and estimation procedures for the vegetation diversity and structure indicator. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-781. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 53 p.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Tadesse G, Zavaleta E, Shennan C (2014). Coffee landscapes as refugia for native woody biodiversity as forest loss continues in southwest Ethiopia. Biol. Conserv. 169:384-391.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Teketay D (2001). Deforestation, wood famine, and environmental degradation in Ethiopia's highland ecosystems: urgent need for action. Northeast Afr. Stud. 8(1):53-76.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Tesfaye MA, Bravo-Oviedo A, Bravo F, Ruiz-Peinado R (2015). Aboveground biomass equations for sustainable production of fuelwood in a native dry tropical afro-montane forest of Ethiopia. Ann For. Sci.

|

|

|

|

|

Tekle K, Hedlund L (2000). Land cover change between 1958 and 1986 in Kalu district, southern Wello, Ethiopia. Mt. Res. Dev. 20:2-51.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

United State Department of Agriculture, Forest Service (USDA) (2003). http://blogs.usda.gov/tag/fs/.

|

|

|

|

|

World Conservation Monitoring Center (WCMC) (1992). Global biodiversity: status of the earth's living resource. London: Champion and Hall.

|

|

|

|

|

World Bank (2000). The World Bank Group Countries: Ethiopia. Washington, D.C.

|

|

|

|

|

World Resources Institute (WRI) (2001). People and Ecosystems: The Frying Web of Life; WRI: Washington,DC, USA.

|

|

|

|

|

Yirdaw E (1996). Deforestation and Forest Plantations in Ethiopia. M. Palo and G. Mery (eds), Sustainable Forestry Challenges for Developing Countries, 327-342. @1996 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands.

Crossref

|

|