Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

This is an attempt to address the complexities and paradoxes surrounding other forms of gender identity beyond the physical. These other forms of identities are considered metaphysical and practised within belief systems, cultures and traditions. A postmodern approach lazed on the theoretical framework of inter-subjectivity is used to examine these women’s metaphysical identities from Igbo and Yoruba perspectives especially how it has been patterned along gender social relations within these socio-cultural worlds. The argument is how can a non-physical forms of identity raise complex gendered stereotypes and deep rooted stigmatizations which affects the women’s social relationships and identity. What is objectionable about paradoxical stereotype is not that they are never true, but rather they are not always true since there is no scientific or universal methodology to either affirm or falsify them. Women metaphysical identities are trapped in cultural religion. Thus, the authors’ discussion will focus on the deconstruction of these belief systems since it is germane to appropriate the metaphysical belief as well as develop an epistemic territory and re-orientate the historical, existential and phenomenological meaning of women identities. This will help in managing gendered social relations; correct the distorted understanding of women’s identity and enhance proper understanding of being woman and human in our cultural worlds.

Key words: Women, Igbo, Yoruba, metaphysics, spiritual identity, culture postmodernism.

INTRODUCTION

The exploitation of women’s sexuality through metaphysical identities is one of the perceptions which still keep women in derogatory status within the trado-cultural consciousness in Africa. In ancient Africa, beliefs were birth out of ignorance, though governed by tradition and confirmed by strange coincidence. In post-colonial era, beliefs are entrenched through mental poisoning which inaugurates attitudes of uncontrollable fear and premonition. Women’s sexuality has been given negative attributes in African societies. The conceptions of witchcraft, spirit-child were all attributes of negative women metaphysical identity. Metaphysical identity gives women a sort of stereotype that affects them in their social relations. Mbiti writes that witches who are mainly women are people with inherit power by means of which they can abandon their bodies at night and go to meet similar people or suck or eat away the life of their victims. It is widely believed in most African cultures that women women are usually blamed for experiences of evil in the society (Ogungbemi, 2007:128; Parrinder, 1974:124; Lawson, 1984:23-4). Among the Ga people of Guinea Coast of West Africa, women are usually possessed by evil demons, which live in them and passed to their daughters at death. The implication of the above perspective is that a woman has two identities: the physical and the metaphysical. The two identities are presented one after the other in the next sub-sections.

Physical identity

Identity can be understood from the perspective of sameness and otherness. Sameness connotes the nature of something without reference to another thing (Amaku, 2004:105). It connotes the autonomy of being as well as the point of departure and return in discussion of the nature of a particular being (ibid). The authors’ daily experience and observation are such that teaches people that identity is connected by resemblance, contingency or causation (Hume, 1978:251-263). In this work identity here has to do with gender; anatomy or biological resemblance. Identity is inextricably linked to the sense of belonging. People perceive themselves through identity, and others see them, as belonging to certain groups and not others. Being part of a group entails active engagement (Díaz-Andreu et al., 2005:2). This resemblance necessitates the classification of one as a woman. Research reveals that human is made up of physical as earlier mention and spiritual otherwise referred to as metaphysical identity. The concept of metaphysical identity is point of discussion in the next sub-section.

Metaphysical identity

Metaphysics has to do with the study of what lies beyond the physical world of sensory experience (Popkin and Stroll, 2008:116). These metaphysical explanation of human identity includes the most general and fundamental characteristics of gendered identities both physical mental and spiritual. In this study the authors shall adopt spiritual to include the metaphysical. Spiritual has to do with connections with the human spirit (Hornby, 2000:1147), whereas identity means who or what someone is. (Hornby, 2000:953). Identity, therefore, is not a static thing, but a continual process (literally, that of identification (Hall and Du Gay, 1996). Identities are constructed through interaction between people, and the process by which people acquire and maintain their identities requires choice and agency. Through agency people define who they are. They are potentially able to choose the groups they want to identify with, although this selection is always constrained by structures beyond their control such as boundaries and their own body. The active role of the individual leads to identities being historical, fluid, subject to persisting change. They are also socially mediated, linked to the broader cultural discourse and are performed through embodiment and action. The concept of identity deployed in this volume, therefore, is not an essentialist, but a strategic and positional one (Díaz-Andreu et al., 2005:3). Identities can be hybrid or multiple and the intersection between different types of identities is one of the most enriching aspects of this study.

It means that metaphysical identity is what someone is in relation to his /her spirit. This is contrasted from physical identity. Women’s spiritual and metaphysical identity means what women are in connection with their human spirits. It is thus described as a complex and challenging interactions between internal (self) and external (spiritual or supernatural) forces within an individual. This issue of spiritual identity may be properly considered as a phenomenon of human nature, worthy of examination. If we can determine its cause, an addition is made to human wealth of knowledge; if not, it must be held as part of our usual constitution.

African concept of identity

Within African traditional belief systems, it is generally believed that humans are both biological and spiritual beings; the biological is expressed in the physical world whereas the spiritual is expresses in the non-physical world. There are also two ontological realms of existences; the supernatural (invisible realm) and the natural (visible realm) (Nwala, 2010:46).

The belief is allied with the ontological conviction that life exists beyond the physical and extends to the spiritual. In order words, the ontology of any distinctively African world-view is replete with spirit: spirit is the animating, sustaining creative life-force of the universe. Spirit is real. It is as real as matter. It reality is primordial and it is if not superior at least as primitive as that of matter. In its pure state it is unembodied (Idonibiye, 1973:83).

The physical world is real as well as an intimate part of the spiritual world. Thus, African thought system cannot condone regimentations because there is a continuous interplay, intermingling and interdependence between spirit (forces) and material world. Okoro also emphasized that Africans consider humans and society to be embodiments of spirituality and physicality (Okoro, 2011:7), thus:

Wisdom consists in the harmonization of the compositions of man and his society. This is usually done in a hierarchized order with the singular purpose of unifying the horizontal and vertical factors in man and in the society (Okoro, 2011: 8).

Humans maintain relationship in the physical world through the human body and the unseen world of gods and spirit through their spiritual aspect. The African world could best be describes in what Nw?ga (1984:25) captured as; a multidimensional field of action admitting of three types of reality; physical, spiritual and abstract … they acknowledge that things may change their nature ... a world view that provides the framework for the goals of community and for the hopes and aspiration for the good life of the individual persons.

Thus the traditional African cultures evolved world views, which are categorised within traditional cosmology as world-views which produce a way of life based on man’s spiritual needs; a socio-religious well-ordered communally integrated way of life. There is no sharp distinction between the religious and the secular, between the natural and the supernatural. Thus cosmological relativism underlies the African worldview. It has be expressed that African traditional religion is excessively pragmatic and utilitarian, as their primary motivation of the traditional human religiosity was purely spiritual (Ekwuru, 1999:75), aimed at striking a balance in relationship, particularly with humans and spirits. The implications of these is that culture can be true and genial; it can be false and hostile (Eboh and Idika, 2019:24). But then, culture embodies morality, creativity, collection of wisdom and world-views.

Justification for the study

Contemporary study points to the fact that in this era of modernization and Christianity, maintaining a balance between humans and spirits in Igbo and Yoruba traditions is highly branded especially in dealing with spiritual identities and their rituals of healing. The identities of women are being presumed through spiritual and metaphysical stereotypes. This is so because Western religious consciousness has become the ideal and those traditional beliefs are assumed fetish, irrational and superstitious. This is in the form of positive affirmation which could affect women, men and humanity. Again, this is a way of calling for new spiritual orientation which will foster tolerance and embrace the respect and recognition among and between sexes.

The authors chose to discuss this issue of women’s spiritual identities under philosophical anthropology. This is because philosophy is distinct in its use of method of rational reflection in an attempt at discovering the most general principles underlying things. Philosophy appeals to the very nature or essence of things. One of the presuppositions of philosophy is its attempt at discovering the most fundamental or underlying and general principles of reality in its various dimensions (Ukpokolo, 2004:5). Philosophy has been described as the principle of explanation that underlines all things without exception, the element common to gods and men, animals and stars, the first ‘whence’ and the last ‘wither’ of the whole cosmic procession, the conditions of all knowing, and the most general rules of human action (James, 1970:11). This means that philosophy tries to understand what is beyond the foreground of the life situation. Philosophy by interrogating the spiritual identities of women in two cultures (Igbo and Yoruba) deals with the fundamental issues and pursues certain varied but connected inquiries; what is spiritual Identity? What are the nature and connection(s) of the spiritual with the physical? What are the grounds for valid belief in the spiritual? How do we know?

This is why the idea of women’s spiritual identity as perceived in the languages of the people is best discussed in philosophical anthropology which is a discipline that seeks to unify the several empirical investigations of human nature in an effort to understand individuals as both creatures of their environment and creators of their own values… it refers to the systematic study of man conducted within philosophy (Ukpokolo, 2004:8).

It is within this meaning that the idea of women spiritual identity has become a philosophical issue rather than religious issue. What is central here is the extent to which the study of women spiritual identities can be an object of systematic and scientific study. Philosophical anthropology involves a conceptual analysis of such issues as whether humans possess a specific human nature. Again it investigates the implications of human possessing diverse natures as in the case of spiritual identity. It is within philosophical anthropology that issues between fragmentation of knowledge and the human condition is discussed. This is why the study of women’s spiritual identities is open for serious philosophical investigations. The kind of philosophical anthropology being proposed here will therefore be based on the following assumptions; a human being is a unified biological organism, capable of action, which has evolved to produce culture and also to be shaped by it (Ukpokolo, 2004:15). This, more so, provokes some accounts on the biological ‘make-up’ and gender behaviour. It also informs the search for sociobiological ideas about women as well as differences between men and women especially of any identifiable biological basis for female (human) behaviour. It will further question the roots of those spiritual differences and their divergences in the biological makeup of the two sexes. In the following chapter, metaphysical identities will be discussed from Igbo and Yoruba perspectives. This will be followed by cross examination of those cultural stereotypes then conclusion will come last.

The Igbo conception of women’s metaphysical identity

In Igbo cosmological anthropology, there are different levels of interdependence; nothing is absolute “Everything, everybody, however apparent independent, depends upon something else; interdependence exhibited as duality or reciprocity, now as ambivalence or complementarities, has always been the fundamental principle in the Igbo philosophy of life” (Ifemesia, 1979:67-8). This interdependence of everything and everybody, more so, account for the traditional belief in the interdependence of humans and spirits. Thus there are categories of spirits; (Anyanwu and Ruch, 1981:87; Iroegbu, 1995:339-41; Okoro, 2011:12) including powerful spirits, good spirits (mmuo oma), bad spirits (ajo mmuo, chi ojo) to mention but a few. Women also participate in this interdependence between the spirits and humans. However, this interaction could be negative or positive. When it is a positive interaction, it means it conforms within the ideals of communal life. But then when it is negative, it becomes problem to the society. In this situation the spirits provides opportunities for the malformation of ties forbidden in the purely human social filed. This function is discharge in two ways; first by providing non-human patterns with whom people can take up relationship forbidden with other human beings. Second, through the mechanism of possessions; by allowing people to ‘become’ spirits and so to play non-human and unacceptable roles; they are debarred from playing as ordinary human beings. This is premised on the belief that being human is metaphysics and metaphysics here is a deductive system. The Igbo women’s spiritual identity is a complex issue in Igbo culture. Sometimes, it is believed that women are usually possessed by strange and bad powers or beings that foster anti-social activities. This is traditionally understood in different ways; this manifest in their ways of life, characters and essentially behaviour. Within the Igbo traditional anthropology, humans are both social and spiritual. Being social is what distinguishes humans living within the community while being spiritual depicts that there is life beyond the physical.

Uchegbue captured this believe in the spiritual as; (Hu)man consists of physical and spiritual (or immaterial) aspects and the (hu)man is made of physical and spiritual substances … (hu)man is a biological and spiritual being … this belief logically presupposes the allied ontological conviction that life exists beyond the physical world and extends to the spiritual. The basic social understanding of existence ... is the firm belief that a community of spirits and of the dead exist alongside the community of human beings and that there is a mutual partnership between them (Uchegbue. 1995:91).

The carnal of this is that there is extra-human and supernatural dimension of life and being human. The spiritual world is very real and intimate. The Igbo cosmology sees human as having more spiritual essence than biological. Humans, therefore, maintain relationship between the physical and spiritual. This relationship between human and the spiritual world is conceived and completely expressed in the sense of the normal social interaction within the extended family, through the transcendental, invisible and enigmatic way (ibid, 92).

There are certain spiritual relationships which can endanger the goodness and fruitfulness of humans’ lives on earth; those relationships are considered negative and abnormal.

Women’s spiritual identities in classical Igbo language and culture

There are different forms of negative spiritual relationships among and within sexes and cultures. For the sake of this study, the authors shall limit their discussion on women. These negative forms of spiritual identities affect woman more than the man. It is diverse among traditions and cultures. These different forms of women spiritual identities in Igbo worldview include; the spirit-child (Nwa mmuo), the water lady (agbo mmiri), Spiritual playmates or comrades (Ogbanje, ojembe, ogbonuke), Nwanyi ihe na ákwà (woman of double personality), spiritual spouses (nwunyi mmuo / dimmuo) and witches (Amosu). These cases and categories of spiritual problems are usually dictated traditionally based on their menaces.

The concept of the spirit-child (Nwa mmuo) is observed in an instance where a child who is usually an only child, well loved by the parents and relatives develops a complex health issues that could not be treated and will surely die leaving her biological parents poorer, childless and stressed. It is believed that the spirit-child is sent to a family to punish them. The child will not allow the biological parents to have another child through her spiritual powers and will definitely die unproductive before her parents. Within the Igbo cosmology, the concept of the spirit child is understood as a psychic pact between the specific girl and the spirit world, which is celebrated by oath-taking, representing the girl’s acceptance of her mission on earth, who is the girl’s parent, friends and relatives. This pact can be broken through the expertise of a strong medicine man (Dibia).

The identity of the water-lady (agbo mmiri) is usually conceived by people who live around the river areas. The woman or young girl identified with this negative interaction is seen going to the stream or river at odd hours. She can be talking and smiling alone along or at the river. She sometimes displays negative attitudes against the normal social-cultural milieu of her traditional settings. She will definitely not get married; if she marries, she will die on the eve of her wedding day or during child-bearing or her husband will die strangely. But then, if her husband is alive, she will not bear a child. Her barrenness will defy all medications and clinical diagnosis. They are viewed as odd especially in terms differing of healing and the inability of their healer to comprehend the nature of their illness. Thus this condition is theorized as anomalous which is in opposition and conflict with normal life of the woman. It is within the cultural setting that she will be identified as possessed by water spirit and traditional prescriptions and rituals are done to separate her from such act and she begins to have her own children. Momoh expressed this reality in his doctrine of ‘existential reality’ where in an environment characterized by water, spirit-beings of the water kingdom are usually the major channel of ritual, worship, explanation of reality, or used as an ontological background to the meaning of life. Thus, Momoh wrote; the simple consideration is the pervasive and strategic role of which an existent plays or had played in one’s life. Whether the existent is natural, fabricated by man or even a superstitious existent is beside the point. The simple question is: does or has the existent played any core or central role in the life of the individual or community? If the answer is positive, chances are that the individual or community will institute a religion or a ritual in honour of that existent (Momoh, 1998:38).

This is to show that the conceptions of spiritual identity of women vary from culture to culture, from community to community. It is important also to note that the universal status of spiritual identity is always localized, generated and informed by surrounding and existential factors as well as coloured by peculiar epistemic contexts. Some things are similar with water-lady and spiritual spouses. It is believed that both case of identity will not marry since they are connected strongly with their spiritual families. It is believed that they have husbands, children and a functional family in the spiritual realm. And until they are properly cut off they will not have a good family life on earth.

The case of Nwanyi ihe na ákwà (woman of double personality), is a situation where a young lady displays two different characters. It is believed that there are two spiritual personalities living in one body. When the first personality is in her, she behaves normally, when the second personality manifests, she behaves abnormally. This is seen in women that steal occasionally, fights furiously occasionally. And after each adventure, she apologizes and confesses that she does not know what happened to her. It is traditionally believed that there is the presence of strange personalities who did not fulfil their destinies before their lives were cut short by death; so they are in perpetual search of bodies to accomplish their destines. There are traditional means of removing the strange personality in her, and she becomes normal again.

Spiritual playmates or comrades (Ogbanje, ojembe, ogbonuke) are of different forms. An instance of ogbonuke is when young woman is identified as having spiritual playmates through some of her attitudes. As a young child she will be crying excessively, uncontrollably and spontaneously without any overt cause sometimes.

The young woman may be suffering from hysterical psychosomatic syndromes. The young woman may as well be excessively careless and causing accidents as a result of the presences of her spiritual playmates. She may still be bedwetting beyond childhood. She may find it difficult to live with others, since Igbo believe that to ‘we are therefore I am’ (Unah, 2018:4; Oni, 2019: 169).

Within the Igbo cosmology, the ogbanje is conceived as a spiritual group or association of children who are members of a group in the spiritual world. They have already taken a decision to be born in the human world in various homes.

They also decide that they will live for a short time and die, all in a group, normally before reaching puberty (Uchegbue, 1995:95). They as well cause pains and shame to any member of their spiritual association that deviates from their covenant. There are preventive and curative rituals from the medicine man.

There are also spiritual spouses (nwunye mmuo / dimmuo). The belief in marital relationship between human beings and spiritual beings abound among the Igbo. Uchegbue noted that;

This belief is inferred from the marital experience of particular individuals with spiritual entities who came to have sex with them at night, from some personal names, from certain propitiatory and matrimonial rituals performed by some individuals and from many Igbo folktales, oral and written (Uchegbue, 1995: 95-6).

There are two identified phenomenon which inform the presence of spiritual spouse in a woman. The first is the case of the wife or husband of one’s former life who either craves the continuation of the marital union from the spiritual world or seeks a redress or revenge for the injustice done to her or him in the former life by the living partner. The second is the belief that some gods or divinities have or seek to have marital relationship with human of opposite sex. Ezeanya opined that in those parts of Africa where deities are represented in human forms, male deities have their female counterparts as wives (Ezeanya, 1976:114). This is rooted in the Igbo cosmological belief that the happenings in the world of men are the reflections of the happenings in the world of the spirits. This can be seen as the thrust of the spirit-human relationship is best understood through our known human parlance. There are also preventive and curative rituals within the Igbo medical and psychological closures though it depends of what the spirit husband is asking for. For instance, in the case of an affective and love-seeking spiritual husband, two alternative rituals are performed; (a) a ritual of acceptance and (a) a ritual exchange. Both ways involve lots of demands in terms of both material and psychological.

The other form of spiritual identity is the witches (Amosu). The term witch connotes a supernatural, mysterious power devoid of scientific explanation. It has been argued that to say that something is mysterious does not necessarily mean that it is beyond explanation. So the possibility of an explanation may exist at least in the future (Oluwole, 1989). In explaining the concept of witches Mbiti (1990:253) stated as follows; Witches, who are mainly women, are people with an inherent power by means of which they can abandon their bodies at night and go to meet with similar people (other witches) or ‘suck’ or ‘eat-away’ the life of their victims (1970:263).

He also wrote that sorcery is an anti-social employment of mystical power, the use of poisonous ingredients put into the food or drink of someone to harm people and their belongings and that it is mainly women who get blamed for experiences of evil kind (Ibid, 262); and many women have suffered and continue to suffer under such accusations. Within the Igbo cosmology, there are epistemic structures of knowing, confirming, preventing and curing these spiritual identities. It is generally believed that eighty per cent of victims are women; it is only on few instances that men are victims. Most of the preventive and curative prescriptions are traditionally rooted and has no scientific bases. These days with modernity and Christianity, the practices are seen as obsolete, pagan practices and lacking in orthodox means.

One of the ways through which these spiritual identities are observed is through their behaviour, social menace, and attitude. It is generally believed that they show who they really are, that is their spiritual side through their behaviour, they as well exhibit odd attitude at unexpected times. Women with issues of spiritual identities are usually unfair to their relations, parents, spouses, friends of who that are their suppose victims (suffer misfortunes originated from them).

Space will not allow the authors to discuss all these here and the traditional explanations of these spiritual identities. This paper moves with the ontological analysis rather than mere phenomenological narrative and description; Table 1 states the categories of their menaces and curative rituals; their curative measures are traditionally accessed and are in various forms; they are living their curative and preventive measures for further research and discussions. Now let examine spiritual identity from the Yoruba perspective.

Yoruba conception of women’s spiritual identity

To understand the nature and status of women’s identity in Yoruba, people must first understand that the identity of women in traditional thought is polarised. The polarity is evident in the philosophical and mythical saying that feature women attitude and contribution to the happenings in the immediate society as well as finding solutions to societal problems. Specifically the Yoruba view of a woman as a member of the larger community is seen in Yoruba mythological explanation of the woman in ?s? ifá ‘??bàrà méjì’; who they portrayed as betrayals, untrustworthy, have no endurance and sexually weak.

Women as weaklings

Wádé Abíb??lá (1978’s) ??bàrà Méjì the mthy on how ??rúnmìlà dated ??r?? before getting married to her. ??rúnmìlà did not ha?e a plesant e?perence after the marraige.This version goes on to portray women as beings lacking in enduring spirit.

They are seen as beings that lack emotional and self-control. This is captured in the relationship between Òrúnmila and his wife, Orò, as follows;

… He consulted oracle on behalf of Òrúnmila when he intended to have Olowo’s daughter Orò as wife. Òrúnmila was away for economic reasons. Orò, the wife of Òrúnmila, after the birth of the third child, settled at Ife. Òrúnmila was invited to Olokun, before leaving Ife; he settled the wife with enough provision and told her that he will be back on the seventeenth day. He gave her provisions enough to make her comfortable for some time. But after three months Òrúnmila did not return, Orò ran out of money and the provisions. Being a big woman, she never engaged in any economic activity. The problem

became complicated with the indefinite absence of her husband. She joined women in the vicinity to collect firewood for sale to generate money. However, on one of the trips to the farm, as a beautiful woman, she befriended Ondááró who gave her a hundred thousand cowries. From their canal knowledge of each other, Oro was impregnated. Oridaro did not own up after finding out that she was Òrúnmila’s wife. She became a single mother to Agbé. She lived on the hundred thousand cowries. After exhausting the money, she had to join others again in the old business, but was deceived by Oigoosun, who paid her two hundred thousand cowries. The union resulted in another pregnancy that produced Aluko. She suffered similar fate as with that of Ondááró, she could not discipline herself as in the third attempt to find money for her upkeep. She had a union with Olúúk????l??, who gave her one million cowries. The union resulted her bringing forth Àgbìgbò, she also raise Àgbìgbò as a single mother…(Abimbola, 1978: 67-73).

Both the spiritual and physical identity of women is already biased within the traditional society portrayed above. This is so because it has been integrated into our traditional folktale and myths in such a way that she is not free in the society. The female is defined as a being that stands in antagonistic opposition and reciprocity with the male gender. The idea of stereotypical women’s identity is traditional and historical; this ideology has been transferred from one generation to another. Next is to consider women’s spiritual identity in traditional Yoruba thought.

Women as ?l?y? / Ìyà mi; (witches)

The spiritual identity of women within the Yoruba traditional thought is not very clear. Yoruba proverbs seems to be positive in the portrayal of women as witches, for example; Bóbìnrin bá pé nílé ?k? a dày? (a woman who lives long in the matrimonial home is always tagged a witch). This implies that it is not too common for a woman to endure matrimonial hardship till old aged. However the Ifa Oracle sees a woman as an ingrate and wicked spiritual being. This claim is captured in ??bàrà Méjì;

A pá ?lá nigi Áj??

O?è abìgi r??r????r??

Adíá fún ??rúnmìlà

Ifá n?l? lèé gbé ?r??

Tíì ?e ?m? Olówu níyàwó… (Ibid, 67)

Big trees are witches abode

O?è with big canopy

??rúnmìlà consulted his oracle

While on his bead to propose to ?r??

That is the daughter of Olówu …

The above quotation implies that Yoruba assumes that witches adorn big trees particularly O?è. Yoruba believed that the ?l?y? ‘witches’ were female beings that descended from heaven. They were among the four hundred and one spiritual beings recorded in Òsá Mejì, one of the Ifa verses thus;

Òòle’ ló ???yìn gùnm??lè

(The root of a house is with raise back)

Bí ?ni arìnm??rìn (Like a slow mover)

Bó bá jà kó rìn (If broken it will move)

A dúró sii (It is immovable)

A dífá fún ??kànlénú irúm?lé

(He was the oracle consultants to 401 spiritual beings)

W??n n?t??run b?? wáyé …

(On their journey from heaven to earth…) (ibid, 84-87)

On the journey of all spiritual beings to the earth, all wore clothes. The witches were naked because they were ingrate and wicked. This is captured in the verse thus;

Gbogbo w??n ló rí a?? bora

They were all wearing clothes

?ùgb??n ihòòhò ni àw?n iyàmi wà

But my mothers were naked …

Nígbà ti w?n dé bod?

On their arrival at the gate of heaven

W?n ò leè l? m??

They were unable to precede the journey

Ojú ?ti w?n …

They were feeling shy

The ?l?y? ‘witches’ pleaded with other spiritual beings to help them cover their nakedness but they all refused, only Òrúnmìlà offered assistance. But they refused to come out of Òrúnmila. They were feeding on his intestine and liver on arrival from heaven. Consequently, after consulting the Oracle, Òrúnìlà had to take them back to the gate of heaven where he met them. There are many arguments on why the female witches (?l?y?) came naked from heaven among other spiritual beings; the authors will not go into this argument in this paper.

This goes to express how the society perceives this kind of spiritual identity mostly associated with women. The above account sees the women as ingrates. However, scholars such as Ogungbemi present a defrent view of Yorùbá women spiritual identity. The scholar argues that witches in Yoruba belief were created to make Yoruba trust God and worship him; to him, without the witches, the Yoruba will not have recourse to worship the Supreme Being Deity because in Yoruba cosmology, witches are the major causes of misfortunes, illness, poverty and death. It is common to accuse old women of witchcraft. However no Yorùbá person dear addressed any woman, publicly, as witches instead, euphemism like awon iya wa (‘our mothers’), or agbalagba (‘the elders’) are used (Ogbungbemi, 2007:128).

Yoruba believe the cult of witches is mostly women who pass their witchcraft spirits to their daughters not sons. This is expressed as ‘Fi gbogbo omo bi obinrin’,

‘?y? ? yí lu ?y?’ (she gave birth to only female children, which multiplies the witchcraft spirit). It is also traditionally believed that passing the art to their daughters will enable them to increase their population and give them their control of their guilds (Ibid, 129). Even though there are good and bad witches, the tensions created in families and communities by the belief in witchcraft are polarizing the essence of human social relations and essence of communal living. This explains why witches are separated from physical human transactions in the society. The fear of attack and manipulation of innocent people informs the Yoruba believe as express in the traditional thought, that whatever belongs to witches is sacred; therefore set aside to avoid their wrath. This obedience to the wishes/the keeping of the witches taboo is captured in Òsá Mejì as;

|

Otún ?y? kangó |

The witches’ right side are hard |

|

Òsì ?y? kingo |

The left sides are hard |

|

Òòsa ló ní kéy? mó jowú òan |

The gods forbids witches from devouring its special cotton cake |

|

… A díá fún Talàbí |

He was Talàbí’s oracle consultant |

|

Om? Òòsa |

Consulted oracle on behalf of Òrúnmila |

|

?fá ?b? láàrin ip??njú |

Ifa was facing a great difficulty |

|

????rùn ló yán, Ni omí dòw??n |

It was dry season, There was drought |

|

Àwón ?l?y? gb?? odòo ti w?n síl?? |

The witches dug a well. |

|

Àw?n èèyàn náà sì gbé ti won |

Human beings also dug well. |

|

Ní àw?n ?l?y? bá lagogo káà kiri pé |

Witches made a decree, |

|

Kí aw?n èèyàn ó má ?e, dé ibi odò aw?n o |

that prohibited human beings from their water source |

|

Nígbà tí odó aw?n èèyàn ò lómi n?nú m?? |

However, human water source dried up |

|

Ní Talàbí bá l? p?nmi ní odò àwón ?l?y? |

Talàbí ventured to fetch from the witches’ water source |

|

Agbe ni aw?n ?l?l?y? sì fi ??? odò |

Agbe was employed by ?l?y? as gate man to the water source |

|

Títí tí Tàlàbí fi p?nmi tán, Agbe ò jí |

Talàbí successfully fetched water because Agbe was fast asleep. |

|

N?jé kí Talàbí ó màa gbé agbè omi náà rú |

Tàlabí’s attempted to place the gorge of water on his head |

|

Ni àdá òòsa tó mú lówó bá lu agbè náà |

But mistakenly hit the gorge with cutlass he was holding |

|

Ní Agbé bá jí |

Agbe woke up |

|

Jíjí tí Agbe jí. Igbe ló fi b?nu |

Agbé alerted the witches |

|

… Gbogbo àwón ?l?y? ba tú jéde |

All the witches came out |

|

… Talàbí h? |

Talàbí took to his heels |

|

Aw?n ?l?y? gbá. W??n fi yá a… |

The witches pursued him hard … (Abimbola, 1978: 88-9) |

The above demonstrates the ground of being a witch in Yoruba thought. The fact is that within the Yoruba cosmology, witches are separated from human endeavours. The witches are sets of beings that are always obeyed to avoid their wrath. In ??sá Méjì, every one obeyed ?l?y? by abstaining from their water source. Anyone who disobeys them always incure their wrath; as in the case of Tàlàbí, that tried to fetch water from the witches separate water source: no body including Aláàfin Abí??dún (the king) came to his rescue while he was pursued, until he got to Òrúnmìlà’s abode. This goes on to show how the idea of the witch affects the psychology of the people and their way of life. Now let us examine another form of spiritual identity in Yoruba anthropology.

The Emèrè cult

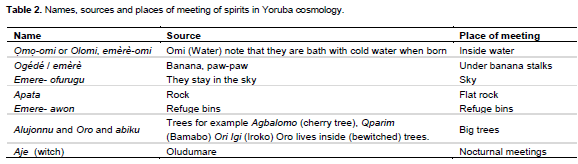

Again, within the Yoruba cosmology, there are various forms of spiritual identities. They are peculiar to both sexes but more on women and female children. It is believe within the traditional ontology that women get in contact with the spirit in many ways, which could as well affect their children. Within the Yoruba cosmology, it is believed that a pregnant woman is not supposed to be out from twelve noon to one pm since it is the time spiritual entities come and interact and could enter the pregnant woman. The Elén?re (female) and Eméré (male) depicts the spiritual identities of humans in Yoruba cosmology. The Yoruba categorized the varying spiritual identities based on their traditional sources. Table 2 shows their sources and the place they have meetings.

These are some of the various spiritual identities in Yoruba cosmology. In the case of the spirit child they usually die young. In some cases, they are given marks on their bodies when they die; and when another child is born, the child comes with the marks inscribed on the dead child. In such instances, a higher form of power is consulted so as to stop the child from untimely death.

This child is called abiku. This idea of abiku (re-occurring still birth) and spiritual identities is widely believed by Yoruba people. It has also given rise to the high attendance and patronage of the white garment churches in Yoruba land. In Yoruba land, it is widely believed that Emere is the general name for spiritual identity pertaining to those that have their source from banana. There are various types of Emere spiritual identity. There is also the alujonnu and oro: They are spiritual identities pertaining to trees. Within the Yoruba traditional cosmology, it is generally believed that alujonnu and oro do not harm people, but then there are wicked people who mix with them and use their influence to harm and initiate human beings. There are also the omo-omi (marine/ mermaid child) who does not harm people but they always have mission and thereabout to turn to females (human beings) in order to accomplish their mission. It is mostly those in the cult or who seek power or refuge from the sect who go down to the spirit world to associate with them.

Philosophy interrogates women’s spiritual identity in Igbo and Yoruba philosophy

From the exposition of the ontology, metaphysics and epistemology of women’s spiritual identities among the Igbo and the Yoruba of southern Nigeria, one can inference that although they were conscious of the difference of gender, these two African nations in the pre-colonial times did not develop stereotypes in which ideally women’s spiritual identities were outraged and mischievously exploited. The issues of spirit-child, spiritual spouses and spiritual comrades and their rituals of healing were not spitefully contrived to exploit femininity but are conceived as a way of solving social-spiritual problem. From our knowledge of spiritual identity, and from our everyday experience, we have many ideas and opinions about what these issues of spiritual identities are like. This is to say that these issues of spiritual identity and their ritual of healings were direct response to perceived theological, spiritual and metaphysical problems of typical traditional settings within a specific time in history.

Given this age of modernity, these ideas of spiritual identities reflect the need for identifying in contract to the true nature and socio-cultural ‘situatedness’ of the women. Since spiritual identities in these cultures are stereotypes, it brings to the fore the need to reshape the social behaviour of women especially those stereotyped. It more so calls for reconceptualization especially in terms of the foundations of learning, social, cultural and even legal and political relations. This is also suggestive of the idea of the comparative worth of women’s lives and personalities. Comparative worth defines women as people in need of protection because they are different from men and there is need to polish this principle of comparative worth beyond philosophical limits.

It is obvious within these cultures that there is something true about their spiritual identities, studies on them have not been systematic and comprehensive. The understanding of them is still within the epistemic closures of cultures that practice them. For a clearer philosophical analysis of the challenges of women’s spiritual identities, we will discuss them under three headings; the problem of context, women’s spiritual identities and resistant culture and finally dealing with dilemma from a postmodernist perspective.

Problem of context

This study on women’s spiritual identities is contextual and relative, creating a perceptual problem within philosophy.

The problem of women’s spiritual identity is that it is culturally oriented. Since there are variations of the conceptions of spiritual identities given these cultures, an examination of the problem of context is useful in understanding the cosmological basis these cultural practices are built on. Again, there are difficulties in attempting to use critical concepts, ideas, theories, terms to understand the nature of spiritual identities of the traditional woman. It is more so difficult to prescribe alternatives to these spiritual identity models. These create gap in understanding and dealing with issues boarding on the reality and challenges of spiritual identities. This deficiency is not grounded in women domination and oppression but serves as critiques that relates to contextualization of feminist issues. But then, it creates the ideology that sees men as fair, and more socially, spiritually and psychologically accurate. This is because the idea of spiritual identities between these two cultures pertains more to women than men. The fact that women were portrayed as oppressed stereotypes, gender minorities and inferior: Women’s spiritual identities add to this as well.

This study also presents the problem of the pluralistic nature of women’s spiritual identities. This is because it dwells within our cultural setting, showing itself in various forms and types, making the problems of women’s spiritual identities subjective and relative. What is meant as spiritual identity varies within cultural settings as exemplified in Igbo and Yoruba cultural settings. Since the spiritual identities of women are cultural, it also gives rise to the problem of methods of explanation. There is lack of concepts with equivalent meanings when translated from source language to target language. This idea has either been over-simplified or lack correct words and connotations for in English language. Most times it is dismissed as superstitions and myths (Otakpo, 2016:28-9).

Another problem generated by women’s spiritual identity is that it is controlled by a traditionally understood ‘cause-effect mechanism.’ It posits the lack of scientific method of verification, testing of hypothesis, no controlling principles, laws or theorems, and moves within the concepts of epistemic closure or secrecy. This is to say that because of the varying cultural realms it operates, its activities are explained by reference to cause and effect within the particular culture: This raises the problem of explanatory models. It is worthwhile to note that women’s spiritual identities are not accounted for in critical literature. Thus it exhibits the same proclivities of patriarchy that renders that account of human incomplete.

The explanation to this is that women’s spiritual experiences are also part of human experiences and as such should be accounted for. The issue of context presents to us the need to censure the idea of spiritual identity as premised on a notion that people are mystified by conservative cultural ideology and consequently cannot remake the world until they see how contingent such idea is. Thus, it is built on the principle of error in that their version of stereotype by consent does not present a realistic picture of women domination by men or spiritual aspects and their psychological consequences.

Women’s metaphysical identity and resistant culture

The problem of spiritual identity is challenging the confidence of the traditional woman in her development model. This is evident in the challenging population structure of traditional and cultural practitioners which vary and add to the high uncertainty in women’s movement, social, political as well as women’s rights groups. In Ekwuru’s (1999:59) words; “… one thing I must tell you is that those things which the white men (modernity and Christianity) came to destroy are still with people and shame to them if they abandon the religion and practice of their fathers.” These controversial issues for women spiritual identities are part of the problems that escalated with the clash of cultures; what may be called the traditional Igbo / Yoruba verses the modern Igbo / Yoruba? is a struggle between deculturisation and depersonalisation.

The place of women’s spiritual identities in Igbo and Yoruba cultures are evident in the art and literature of each culture. Even with the influence of Western education and religion (Christianity and Islam), the problem of women’s spiritual identities still persist. The exigence of this situation of dual cultural existence puts the woman in a state of a tragic clash of values, and unconsciously imbues in their social personality a form of schizophrenic pathology with paranoid tendencies. This has brought the woman under a stereotyped socio-anthropological surveillance. Part of the objectives of this essay is to propose a way to help women and the society at large re-think and overcome these stereotypes. This research proposed three projects;

1) Reconstruction of the existing culture (the culture of spiritual identity and its manifestations) through consolidation with a more rational culture. This is purely inventive not recovery moves.

2) To make conscious efforts to enter into this discourse of spiritual identities (discourse on this area is minimal within scholarly writing) within indigenous belief systems; that is to mix with it, transform it to make it acknowledged instead of marginalized, stereotyped or supressed or as forgotten history. This is because; some traditional women still holds this system tenaciously.

3) It is time to put resilient culture towards a more integrative view of human community

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors have not declared any conflicts of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Abimbola W (1978). Ìjinkè Ohìm Enu Ifá Apá Kejì Aw?n Ifá M lánálá (2nd Edition), Nigeria. Oxford University Press. |

|

|

Amaku EE (2004). Language as a Powerful Expression of Human Dignity and Cultural Identity. Journal of Igbo Youths and their Language. |

|

|

Anyanwu KC, Ruch EA (1981). African Philosophy: An introduction to the main philosophical trends in contemporary Africa. Rome: Catholic Book Agency. |

|

|

Díaz-Andreu M, Lucy S, Babic S, Edwards DN (2005). Archaeology of Identity. Taylor & Francis. |

|

|

Eboh MP, Idika CMN (2019). "Igbo Culture, Creative thinking and Moral Development, in African Moral Character and creative thinking Principles, Unah Jim I. (ed.), Ife: University of Ife Press pp. 23-44. |

|

|

Ekwuru EG (1999). The Pangs of an African Culture in Travail, Uwa Ndi Igbo Yaghara Ayagha, Owerri, Imo State: Totan Publishers Limited. |

|

|

Ezeanya SN (1976). Women in African Traditional Religion. Orita: Ibadan Journal of Religious Studies. 10(2):105-121. Available at: |

|

|

Idonibiye DE (1973). The Idea of African Philosophy: The Concept of Spirit in African Metaphysics in Second Order: An African Journal of Philosophy 11(1):83. |

|

|

Ifemesia C (1979). Traditional Human Living among the Igbo; A Historical Perspective, Enugu: Fourth Dimension Publishers. |

|

|

Iroegbu P (1995). The Kpim of Philosophy. Owerri: International University Press. |

|

|

James W (1970). Selected Paper on Philosophy, in History of Philosophy, London: Hodder and Stoughton. |

|

|

Lawson TE (1984). Religions in Africa, NewYork: Harper and Roll. |

|

|

Hall S, Du Gay P (1996). Questions of Cultural Identity: SAGE Publications. Sage pp. 1-17. |

|

|

Hornby AS (2000). Oxford Advances Learner's Dictionary. Sixth edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

|

|

Hume D (1978). Of Personal Identity in A Treatise of Human Nature. Selby-Bigge edition, revised by Nidditch PH. Oxford: Oxford University Press pp. 251-263. |

|

|

Mbiti JS (1990). African religions and philosophy. Heinemann. |

|

|

Momoh CS (1998). The Substance of African Philosophy, Auchi: African Philosophy Projects' Publications. |

|

|

Nwala TU (2010). Igbo Philosophy. third edition. Abuja: Niger Books and publishing Company Limited. |

|

|

Nw?ga D (1984). Nka na Nzere: The Focus of Igbo Worldwide, Ahiajoku Lectures, Owerri; Ministry of Information, Culture, Youth and Sports. |

|

|

Okoro C (2011). The notion of integrative metaphysics and its relevance to contemporary world order. Integrative Humanism Journal 2(2):3-28. |

|

|

Ogungbile DO (2015). African indigenous religious traditions in local and global contexts: perspectives on Nigeria. Malthouse Press. |

|

|

Ogungbemi S (2007). Philosophy and Development, Ibadan- Nigeria: Hope Publications. |

|

|

Oluwole S (1989). Witchcraft, Re-incarnation and God-Head. Ikeja: Excel Publication. |

|

|

Oni MO (2019). Being with Others: Metaphysical Pedagogy for Social Peace, in African Moral Character and creative thinking Principles, Unah Jim I. (ed.). Ife: University of Ife Press pp. 163-174. |

|

|

Otakpo N (2016). Idegbe: Linage Continuity through a Daughter. Benin: University of Benin Press. |

|

|

Parrinder GE (1974). African Traditional Religion, London: Sheldon Press. |

|

|

Popkin RH, Stroll A (2008). Filosofia per tutti (Vol. 17). Il saggiatore. |

|

|

Uchegbue CO (1995). The Concept of Man's Spiritual Companions in Igbo Traditional Thought" in Footmarks on African Philosophy. Uduigwomen AF (ed.). Ikeja-Lagos: Obaroh and Ogbinaka Publishers Limited. |

|

|

Ukpokolo IE (2004). Philosophy Interrogates Culture, A Discourse in Philosophical Anthropology. Ibadan: Hope Publication. |

|

|

Unah JI (2018). African Philosophy and Phenomenology of Peace. Lagos: Concept Publications. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0