ABSTRACT

The study, Conspicuously Absent: Women’s Role in Conflict Resolution and Peace Building in Northern Uganda in the Context of United Nations Resolution 1325. The research was carried out in war ravaged Acholi sub region covering the districts of Amuru, Gulu, Kitgum and Pader because they are located in the centre of Northern Uganda conflict between the Government and the rebels commonly known as the Lord’s Resistant Army (LRA). The main objective of the study was to locate women in conflict situations and assess their contribution. The study methodology is qualitative and builds upon a review of related literature, oral interviews, questionnaires and focus group discussions with men and women who participated in the study. The major research finding reveals that women played a big role in peace building and conflict resolution, but their involvement remained unrecognized. Worst still, the northern Uganda women appeared not linked with the growing number of women led initiatives internationally, nationally and sub-national levels. The lack of recognition of women’s roles makes women invisible actors in peace processes taking place in northern Uganda. The study concludes that including women in the formal peace process, while not a goal in itself, is symbolic and significant step in the promotion of women’s justifiable participation in peace building and conflict transformation processes. The study makes recommendations to enhance women’s capacity to contribute to peace processes formally and informally.

Key words: Conflict mitigation, conflict resolution, gender, resolution 1325, peace-building, Lord’s Resistant Army (LRA), sub- region.

The women, peace, and security agenda, first articulated in United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1325 in 2000, seeks to elevate the role of women in conflict management, conflict resolution, and sustainable peace. The agenda can be promoted in various ways, including National Action Plans (NAPs) on women, peace, and security (Roslyn et al., 2017). The above quotation suggests the inclusion of gender perspective to conflict resolution and peace building. Thus, this study investigates the theme, Conspicuously Absent: The Role

of Women in Conflict Resolution and Peace Building in Northern Uganda in the Context of Resolution 1325. The Sustainable Development Goals promoted by United Nations (UN) for meaningful growth in UN member countries and the rest of the world politically, socially, economically calls for active involvement of men and women (Nkosazana, 2013). The study recognizes that it is a human and constitutional right of women to participate in nation building processes. Therefore, the building of a harmonious, peaceful and just society is a moral duty and obligation for all the genders. The need for women to play active roles in development including conflictual circumstances, peace and security is greater in the 21st century than ever before.

In this study, women of Northern Uganda articulated and voiced their frustrations about their limited participation attributing it to Acholi culture saying, “We women are not allowed by our overly domineering husbands to take decisions. Even in the peace talks, we do not have an opportunity to decide. We wait for the men to decide although some women have now defied the rules.” Therefore, there is great necessity for women to be empowered in order that they might make direct inputs to peace building processes. Women should expect to enter the formal political and economic arena only when they acquire relevant skills through the right training and support. The views of the Acholi women expressed in this study are corroborated by Margot (2018) who argued that Culture is not an excuse for oppressing women. It is imperative for women to acquire relevant skills, capabilities and self confidence to demand for not only their human rights but also to fundamentally organize for change in the status quo.

Background to the study

Since 2009, the story of northern Uganda has greatly changed from insecurity, hunger, hostilities, violence and Internal Displaced Persons (IDP) camps, to a narrative of relative peace and post conflict reconstruction. Women and men are becoming farmers and business persons again traveling freely by night or day to and from Kampala and the rest of East Africa and beyond. The sound of (African and Western) music fills the air again at entry point into the Acholi sub region. Children are attending school at all levels. The Acholi sub region is awash with Government and Non-Governmental activities targeting post conflict reconstruction agenda makes the region a beehive of development activities. People are concerned with recovery, rebuilding and rehabilitation of war traumatized victims as well as reintegration of ex- combatants and other war returnees. Meanwhile at The Hague, the International Criminal Court (ICC)’s Headquarters, Dominic Ongwen, one of the rebel leaders closest to Joseph Kony, is facing trial for war crimes and crimes against humanity (International Refugee Rights Initiative, 2011). This trial is of great importance to women and men of northern Uganda who suffered so much as a result of the protracted violent conflict. Many people follow the proceedings of the trial via satellite waves, national television, broadcasters and radios.

This study demonstrated that Ugandan women are increasingly becoming significant actors in many spheres of everyday life and their participation in national and international issues could no longer be ignored. The numerous actors involved in working toward conflict resolution in northern region could not afford to ignore the roles played by women. Fundamentally, it is a matter of fairness and social justice because women, like men, have constitutional and human rights despite diversity of human experiences and perceptions. Therefore, it is a moral duty and obligation of women and men to work together in forging a just and peaceful Uganda. At another level women are already playing significant roles in peace building mainly at the grassroots level in northern Uganda, a region plagued by conflict between the Lord’s Resistant Army (LRA) and government of Uganda for over two decades (Angom, 2018; Musinguzi, 2019). In short, the roles that women play in peace building particularly at the grassroots communities in northern Uganda can no longer be down played or even ignored. The findings indicate that Northern Uganda women are important yet unrecognized actors in conflict transformation processes. In one sense, they contribute much to conflict mitigation and peace building using their social status as mothers of the nation as revealed by the research.

However, increasingly women in the conflict affected districts of Amuru, Gulu, Kitgum and Pader and affected areas assumed traditionally male roles which in many cases are a conscious response to social needs arising from the absence or death of men as a result of conflict and displacement. For instance, where husbands have been killed, women have taken on the duty of providing for families. Such examples challenge the patriarchal notion of women as inactive members of society and passive victims of war. Nevertheless, the voices of women living in situations of armed conflicts throughout the world have too often been excluded from decision making bodies and peace negotiations.

Sanam (2007) reflecting on “women building peace, what they do, Why it matters,” observed that “ while women remain absent or marginalized from the formal peace processes, they are conspicuously active in the informal, grassroots peace building activities. Invisibility, activity, victimhood and agency run parallel.” In her view, at the 1995 United Nations’ fourth world conference at Beijing, China the many participants were still overwhelmed by the war in Bosnia and the human tragedy of Rwandan genocide. Although information about women was still limited, the trends are alarmingly changing. The conference delegates expressed a great need to add to the exiting document, platforms for action that focus purposely on women’s experiences in armed conflict. The Beijing Conference scored big on women issues. Firstly, it mobilized global networks of women working to achieve peace and security. Secondly, the formulation of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on “Women, peace and Security” which was viewed as a milestone was a turning point. Sanam maintained that the 1995 fourth conference on women greatly empowered them to bring new energy and focus to peace building as they take on regional policy making institutions and other international organizations.

In recognition of women’s capabilities to promote peace, on 31st October 2000, the United Nations Security Council declared and adopted Resolution 1325 which became a landmark document recognizing the needs, rights, and experiences of women and girls in armed conflict (Nkosazana, 2013). Even as the resolution highlights the need for improved responsiveness to women’s protection and security concerns, women continue to face gender based violence and are often not regarded mere victims. However, the resolution recognizes the importance of increasing women’s participation in peace building, conflict and post conflict reconstruction processes as well as supporting women’s peace initiatives. At the policy level, some progress was made in exploring ways of incorporating Resolution 1325 in peace building processes internationally. For instance, the Norwegian Strategic Framework for peace building stated that “Norway is seeking to mainstream gender perspectives into all processes and at every level of conflict prevention and peace promoting efforts.

In Uganda, however where conflict and peace processes seeking to resolve the dispute were ongoing, the research findings reveal that little is known about Resolution 1325 or its aims, making its implementation difficult. This is true particularly of women’s under representation in the peace talks between the Lord’s Resistant Army and Government (2006) in Juba, South Sudan. Although South Sudan did not became a sovereign country until 11th July 2011, the ability of the autonomous Government of South Sudan to make a smooth transition of political power without major struggle for leadership from John Garang (late) to Salva Kiir Mayadit who deputized Garang earned the regional government great respect especially among other African states. This explains why Uganda’s peace talks took place in Juba, becoming the state capital of South Sudan since 2011.

This exclusion of women coupled with the apparent lack of awareness of the Resolution 1325, prompted this research work with the aim of assessing the impact of the Resolution on women in peace building and conflict resolution. It is important to note that United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM), Uganda carried out similar consultations on the impact of the Resolution 1325 in partnership with UNIFEM-Africa on Darfur and Somalia. This research concurred with UNIFEM on two major aspects:

(1) Women in Northern Uganda were tired of the war. They demanded strenuously for peace no matter the costs. As far as the women were concerned the negotiating parties in should not return to Uganda unless a peace settlement was realized.

(2) Largely women in northern Uganda had little or no knowledge of Resolution 1325 and the ways in which it seeks to involve them in the process of conflict resolution and peace building. Therefore, although women in northern Uganda expressed deep-seated disappointment regarding their lack of representation in the formal peace process, they are generally unaware of their right to participate.

Women were conspicuously absent in the formal Peace process of Uganda back. This is in line with Sanam (2016) who argued that “women’s experiences and voices are often discarded and erased from decision-making processes and even from history.” In the case of northern Uganda, grassroots women felt excluded from the official peace processes because there was no clear avenue through which they could actively present their expectations. Furthermore, women were numerically weaker compared to their male counterparts in terms of representation and participation in the peace process.

Despite that fact that women had their fingers on the pulse of their communities, and fought to keep the fabric of their families together in the conflict situations, women in Northern Uganda were greatly concerned about their under representation. Thus, respondents to the study demanded to know how civil society organizations would make their voice heard with regards to the peace talks. Clearly Northern women had a profound personal, national interest, and commitment to the pacification of Uganda but women were marginalized in the official peace process. As people directly affected by conflict, they needed to own the proposed solutions through direct participation in peace process. However, it should be noted that concerns over the lack of women representation in the official peace process was not only about mere numerical physical presence, but more critically their capacity to discuss and articulate issues in order to influence the outcomes of the peace talks.

Significance of R 1325 to the conflict situation in Northern Uganda

The civil war in Northern Uganda appeared to have been forgotten by the international community for very long time. This research upholds contrary view. Northern Uganda was not a forgotten region. As early as 2000, the UN had begun to rethink its policies on peace building in its quest for conflict free world and identified women as the major missing link in conflict resolution and peace building and security. The declaration and adoption of the Resolution 1325 by the United Nations Security Council brought on board many governments as signatories committed to domesticate and implement the issues on “women, peace and security in their local settings in an effort to make the world peaceful conflict free.

In the Ugandan context, it was apparent that little or no concrete action plan was taken to operationalize the principles of Resolution 1325. Most policy discussions and donor efforts on conflict resolution and post conflict reconstruction lacked gender specific perspectives. In retrospect, (2004), Kofi Anan, the former UN secretary General, reported on several initiatives taking place to make the aims of Resolution 1325 practical (Ramšak, 2015). Despite significant achievements realized, there were major gaps. The said gaps included areas like women’s participation in conflict prevention, peace building, and integration of gender evaluation situation in the expected peace agreement and processes all of which could draw attention to the roles of women in post conflict reconstruction as well as women’s representation in decision making (Kimotho, 2017).

The Northern Ugandan conflict prevailed for more than 20 years. (Osborne, 2019), suggesting that the war was one of the longest conflicts in the African continent. Women and children were major victims (Andrabi, 2019). At global level, however, by 2000 the United Nations, a global organization, began to rethink its policies on peace and security and realized that women were a significant missing link in achievement of conflict resolution and peace building. The declaration and adoption of the Resolution 1325 by the United Nations Security Council led to several studies aimed at establishing the extent to which the Resolution 1325 enhanced women’s involvement in conflict resolution and peace building by Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) in selected African countries including Rwanda, Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Kenya. However, no such study was undertaken in Uganda.

Statement of the problem

Whereas the people of Northern Uganda experienced great suffering as a result of the protracted war, women and children bore the brunt of the conflict in the two decades of violent hostilities. Rape, abductions and killings were the order of day committed not only by rebel forces but also by forces loyal to the government. Despite prevailing insecurity and lack of political stability, women played significant roles with regard to the socio-economic welfare of the conflict stricken communities. However, women remained invisible actors in all this, suggesting that women are treated as insignificant beings that can nearly always be taken for granted. The active roles women played remained painfully unappreciated and unrecognized in the Ugandan context and elsewhere in the world as observed by Sanam (2007).

Objective(s) of the study

The main purpose of the study was to capture the reality of life as seen and experienced by women living in armed conflict situation in Northern Uganda and to find out women’s contributions to peace building and conflict mitigation and resolution in the light of the principles expressed in Resolution 1325. The specific objectives of the study were:

(i) To assess the contributions of women to peace initiatives at the grassroots level in mitigating conflict and promoting societal cohesion in northern Uganda.

(ii) To identify major challenges to women’s participation in resolving conflict in northern Uganda.

(iii) To identify key strategies for effective participation of women in resolving conflict according to the principles of UN Resolution 1325.

Justification of the study

In Uganda, private sector led mainly non-governmental organizations’ initiatives targeted grassroots community action to promote peace through reconciliation and reintegration. Although women were represented in some political levels by women cabinet ministers and members of parliament, recognition of women’s efforts at the grassroots do not seem to reflect governance structures beyond the family. This suggests that as typical patriarchal society, women’s governance tends to be perceived as important mainly at house hold levels.

Again, the war devastated properties and lives. Thousands of men, women, and children in northern Uganda perished senselessly. As mention before, women/girls were targets of rape, abductions, forced marriages and HIV/AIDS infection in the armed conflict situation (Okiror, 2016). Yet women remained conspicuously absent in the official peace processes. Thus, it is necessary to document the horrific narrative of the women of Northern Uganda for the global community to hear their voices and know their plight.

The study views women as stake holders in conflict resolution and sought to document their involvement conflict resolution and mitigation. Hence their exclusion from peace process meant that what they did, contributed and the challenges they faced in conflict situations and peace building would not capture the attention of the key actors in pacification processes. Although adopted unanimously in 2000, the implementation of Resolution 1325 met many challenges. Studies show that since the adoption to of Resolution 1325, awareness of its importance of including women in peace building and post conflict reconstruction processes grew tremendously. It is important to note that the implementation of the resolution remained erratic and unplanned, suggesting that it was systematical implemented by all UN member states. However in the last 19 years or so, some of principles of the Resolution 1325 were factored in peace processes that serve as a model for northern Uganda. For instance, the same report noted that in Liberia, some Disarmament, Demobilization and Reconstruction (DDR) assembly points met the requirement of Resolution 1325. The sites were fenced off and separate compounds were created for women, men, girls and boys. Gender specific assessments were undertaken and counseling services offered. Elsewhere in Africa, the Inter-governmental Authority responded to the mandate of Resolution 1325 by successfully advocating for women’s participation in 2002/2004 Somali peace talks. Consequently, women were involved in the agreement drafting commission. As a matter of facts one woman even signed the accord on behalf of women and civil society as well as actively participating in constitution-making processes (Sakuntala, 2019). By Comparison, in Uganda, Resolution 1325 apparently registered little impact on efforts towards peace suggesting a lack of public awareness. Therefore, this study is justified because it proposes strategies for identifying issues and challenges faced by women in peace building and conflict resolution processes and strategies for their involvement.

Significance of the study

Questions concerning the role of women and their absence in conflict resolution and peace building processes were the basis for gathering primary data. The findings was of great importance to government of Uganda, development associates including Non-Governmental Organizations, donors, civil society organizations and policy makers who influence decisions and actions plans undertaken to improve peace building with specific reference to women’s participation in issues of protection, security, conflict mitigation and resolution. The study was based on primary data and answers questions concerning the role of women in conflict resolution and peace building. Therefore, the study sought to fill a knowledge gap in the current literature by focusing on the findings of past research works appropriate to conflict resolution and peace building.

Scope of the study

The study was carried out in Acholi sub region. According to the following statistics: Amuru (20%), Gulu (20%), Kitgum (30%) and Pader (30%). A total of 230 people participated in the study. The rationale for the choice of the selected areas was because of their location in the heart of conflict ravaged region. The time period focuses on period of the conflict from 1986-2006. The thrust of the research was the roles of in conflict resolution and peace building in northern Uganda. The activities and events that took place within the specified period are given much emphasis.

The materials used in this study comprised Literature that is, journals, magazines, newspaper, and archives and books, researcher(s), sample participants and equipment such as recorder, transcribing machines, note books and pens.

Data collection methods

The research employed qualitative research method to obtain the primary data through in-depth interviews, questionnaires and focus group discussions. The use of in-depth interviews method for data collection allows greater depth of discussion and better understanding of the more subtle aspects of people’s understanding and thinking around the issues referred earlier in the study. Quick Information Capture (QIC) method was employed to rapidly collect primary data. Collection of secondary data involved review of related literature on women in journals, magazines, newspaper, and archives and books. In addition, relevant aspects of the quantitative approach such as percentage, tabulation and graphs were used in this research because they aid clarity of concepts.

Study participants (sample population)

In this study, the sample population is in fact the study participants. Both men and women were targeted to find out their perceptions of Resolution 1325 and women’s roles in conflict mitigation and security in the sub region. A total sample of 230 women (66%) and men (34%) from Amuru, Gulu, Kitgum and Pader districts took part in the study. One hundred fifty persons answered questionnaires, twenty key informants from the four districts were interviewed individually along with district women’s leaders and chair persons, while sixty people participated in focus group discussions in 20 different groups. Recognizing that leadership is important in grassroots communities’ understanding technical documents such as Resolution 1325 was critical. Interviews were conducted with community representatives and leaders. People in position of authority including women councilors and political leaders such as Local Council chairpersons, district gender officers, members of Parliament, community officers and leaders of women’s groups and other organizations were also interviewed. The goal was to consult women on their perceptions, experiences and roles in conflict resolution and peace building in northern Uganda.

To guide the data collection, research questions were formulated aimed at investigating the roles women in conflict resolution and peace building in northern Uganda. The interviews asked open ended questions and allowed people to follow their own train of thoughts thereafter. This technique tended to brings out the respondents’ personal experiences, memories, and perceptions of reality, enabling them to identify what is important and true for them in their specific context. On the bases of their personal experiences, memories and perceptions of life, the focus groups discussions allowed women to give oral testimonies that augmented individual interviews and questionnaires.

Data analysis

Data analysis involved utilization of several techniques including: transcription, compilation, recording, coding, categorization, symbolic representation, editing, and interpretation of meanings. The data collected was transcribed, recoded, and coded daily to capture the key categories of variables within the research as a basis for generating content. The data collected was then described, categorized and classified according to concepts and symbols. Naming, labeling and qualifying research variables characterized this process.

The study recognizes that little is known about the countless ways women interact with conflict at the grassroots level in relations to peace building at a community or family levels. Thus, this section presents and analyzes the field research findings, showing the actual roles played by women in a situation of armed conflict and the understanding of their roles at a more structural level in any conflict resolution processes. The findings revealed that women engaged in a variety of community activities such as: mobilization to address salient neighborhoods issues, psychosocial support networks, and active engagement in conflict resolution and livelihood support which enabled women to hold families together, as family is the basic social unit of a society which was adversely affected by the conflict in northern Uganda.

Socio-economic roles of women at a grassroots level

Here discusses the numerous ways women participated directly or indirectly in community activities that could be interpreted as peace building. The primary indications of women’s participation in conflict resolution processes were evident in various socio-economic aspects. The research highlighted a number of relevant examples outlined below:

(i) There were many instances where women played primary roles in community mobilization in activities like information dissemination and other social activities throughout the research. Women were actively involved in community activities such as burials and marriages. It should be noted that African burial and marriage ceremonies denote a sense of belonging, identify, and kinship. Hence it is always a social obligation to grief and share joy with the affected family, community which in effect minimizing personal social tension and stress arising from lack of social support. The strong sense social support could help mitigate conflict and increases opportunities for peace. However, the impact their socio-economic activities were limited to communal and domestic works like cooking and cleaning. Furthermore, women were good custodians of community resources such as boreholes, equipment ensuring that water resources were properly sustained. It is needs to be pointed out that provision of water and clean, safe water is still a scarce resource. This is even worse in conflict situations. Therefore, keeping good custody such as boreholes as sources clean water and related equipments could go al long way in peace building. Sometimes women and girls could fight at the water points over who should get water first or last. The ground rule was often first come, first served. When such rules are disregards by some individuals, fighting could break out and damages caused to property and injuries to persons. Furthermore, the use of borehole could be regulated by locking and opening at specific times. When communities were properly sensitized on when to go or not to go for water, only could everyone live in peace.

(ii) The conflict deprived men of income generating opportunities. Idleness and high rates of alcohol consumption rendered them powerless. Undoubtedly, men were traditionally responsible for holding families together. Due to the conflict, provision of food, health care, shelter and other basic needs such as education were taken over by women. Whereas, women’s roles were mainly domestic in nature, and the long-established practices were based on patriarchal systems which provided for men to be heads of households and the bread winners of their families, many women increasingly assumed the role of being bread winners and hence de facto family heads. This change came about as consequence of the conflict and displacement; they not only produced children but also looked after them and the whole families. They taught children poems, songs, and told stories and sometimes discipline them. Therefore, women effectively administered their families and gave encouragement and hope better future. As women assumed new responsibilities as head of house hold, decision makers, and providers of basic needs like food, education etc, they invariable contributed to peace building at the grassroots level. Since peace building begins with the family, women contributed much to peace building while most men drank away such opportunities and despaired feeling powerless partly as a result of conflict.

(iii) The research revealed that frequently women arranged group meetings and contributed some cash of 200/ Uganda shillings per person or other contributions in kind in order to raise money. The women’s groups operated on the basis of self-help initiatives by community. During these meetings they often incorporated issues of peace building, for example, they sang songs and acted plays that recalled the atrocities they underwent and suggested solutions to the identified challenges.

Women in peace building and conflict resolution in Northern Uganda

During the field study, a female respondent, whose identity is withheld, said this about her personal effort in peace building and conflict resolution: I was able to prevent a big violent clash between the youths from rivaling zones in the camp. I did this by advising the camp leadership to call an urgent meeting in which we appealed to our children to stop all acts of violence.

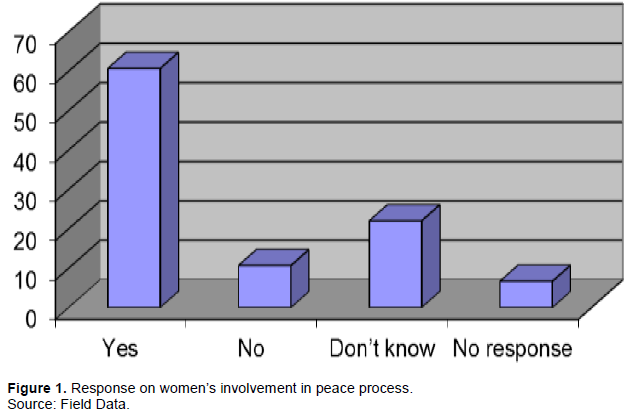

The quote confirms the involvement of women in peace building even as individuals. The message of women like the respondent mentioned here when taken seriously and acted upon could result in a positive change of attitude and behavior. When as asked whether women took part in the peace process at local level, their responses were varied as shown in Figure 1.

As shown in Figure 1, participants’ responses indicating women’s actual involvement in peace building processes at the local community level were varied. However, it is clear that grassroots women in northern Uganda were actively participating in peace building in their communities even before the Juba Talks. Women’s response to the question seek to find the level of participation of the grassroots women in peace building process, about 58% of respondents said that women were involved in peace building especially at village and household levels. Their level of involvement was quite high for persons whose space in the context of human freedom was reduced by conflict. However, it is also important to note that 19% of the respondents were not aware of any women led peace initiatives at the grassroots level while about 10 % indicated that women were actually not involved at all in conflict resolution and 7% made no response. This was possibly because defining what constitutes peace building and conflict resolution at the grassroots level was quite a challenging task since the research did not limit the respondents by putting parameters in place to define the two concepts. Despite this mentioned challenge, the findings revealed that the majority of the respondents were aware of the role women played in conflict resolution at the grassroots level although the level of awareness still needed enhancement through deliberate sensitization programs.

Advocacy for peace through prayers

While conflict is sometimes influenced by religious sectarianism, in the case of Northern Uganda religion served as a vehicle for peace building through promotion of reconciliation, tolerance, and unity. Through counseling, trauma and dissenting views were accommodated. From this study it was clear that many Ugandans appealed for divine help and used religion to solve any challenges the face in life. This explains why many women thronged worship centers regularly, suggesting the significance of religion as tool for conflict resolution and peace building. While experiencing insecurity, abject poverty, helplessness and hopelessness in Internally Displaced Persons camps, women in particular discovered that religion no doubt inspired hope for a better future. This hope kept both women and men going to derive strength in the face of adversity. The study underscores the constructive use of religion for peace building in the scenario of northern Uganda. Religion was a unifying factor bring together from various religious backgrounds including Catholics, Anglicans, as well as Moslems. The leaders of the religions mentioned were mainly Bishops and Archbishop and they established a Faith Based Organization, the Acholi Religious Peace Initiative. This is evident in the great role that Acholi religious leaders played in the initial efforts for dialogue between the rebels and Government of Uganda aimed at resolving the conflict. The table below show peace related activities by women in northern Uganda. Women like, Reverend Sister Theresa Lakot, who represented women on the Acholi Religious Peace Initiative played a great role of advocacy for prayers in the struggle for peace in northern Uganda. To better gain insights into the activities women engaged in northern Uganda, the percentages were shown in Table 1 and both genders said on women’s involvement in church are also shown.

The Table 1 reflected on the perception of both genders regarding women who were involved in Church. From the table majority of women (59%) said they used religion as means of building peace in their communities. Again, 14% of the respondents mentioned counseling and mediating family conflicts as critical to attainance of peace. 12% of respondents expressed awareness of community mobilization, development, participation in church activities including teaching Sunday schools and guiding children to mention but a few. Meanwhile 6.7% of the respondents were unaware of any particular peace activities involving women’s active participation. About 4% of the respondents said that informal peace education was done by guiding and teaching children how to lead peaceful and meaningful lives through poems, songs, and traditional dances.

Counseling and mediating in family context

In the context of the war and displacement, women came under increasing pressure to maintain unity of the family even as incidences of family disintegration were widespread. Women were involved in resolving disputes between and within their own families especially with regard to children. In the (IDP) camps, conflict between and within families were rampant due to scarcity of resources like food, water and utensils among others. Child up bringing in a camp situation can be an uphill task since children are part of a large group of camp children coming from different social backgrounds (Hovil and Lomo, 2015). Thus, by securing the safety and welfare of children as the future youths of post conflict northern Uganda, women contributed to working and ensuring peace.

Participating in peace activities as individuals and groups

Although women were overlooked in the formal peace process, the study shows that 60% of the respondents noted that there was growing recognition of the fact that women, individually and groups, played significant roles in the pacification of northern Uganda. From interviews conducted in Amuru, district the respondents said that the most recognized individual woman was Achan Betty Bigombe, renowned for her role in initiating peace talks with the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). Betty Bigombe was the only woman who made efforts to meet Joseph Kony, the rebel leader, in the early days of the conflict. It is widely perceived that some men felt offended that a woman’s effort in bringing peace could make history in the long run. Further, the participants observed that other grassroots women like Angelina Achieng who also doubled as Co-founder of Concern Parents’ Association even won peace award demonstrating recognition for role in peace building. Such women were recognized as bearers of peace torch in the various areas of the conflict in northern Uganda.

Receiving and reintegrating returnees

Women also played a great role in receiving and taking care of returnees given the stigmatization and hatred from community members who regarded them as murderers and rebels. The return and reintegration process of ex-abductees was another challenge requiring counseling skills, provision of psychosocial support and mediating particularly when the returnee committed atrocities in a given community. Women did all these without any formal skills in counseling. These daunting tasks ere braved by women mainly because they consider the returnees as their own children, brothers, sisters and husbands. Admittedly, NGOs like World Vision did much in the area of psycho-social support, but much more was desired due to the overwhelming need for this social programme. The study observed that a clear lack of access to formal counseling programs/services was prevalent as psychologists and psychiatrists in this region were numerically inadequate or were forced out by the conflict. On the question of reintegration, Studies carried out by Quaker Peace and Social Witness (QPSW) (2008) observed and argued that initial DDR programmes put in place by government were inadequate. The Quaker Peace and Social Witness urged for a more comprehensive disarmament, demobilization or re-interegration programmes should be developed while taking into account concerns of justice, reconciliation, gender and livelihood of foot soldiers. Women’s involvement in DDR was negligible with many feeling excluded. This is could be because the numerical presence of male ex-combatants attracted most DDR programs at expense of women, hence undermining women’s participation in DDR that was critical for peace building in northern Uganda. As mentioned earlier the war stripped men politically, economically, social and psychologically, and spiritually and rendered them helpless. During the two decades of war, the region of Northern Uganda was under military rule of the Kampala-based National Resistant Movement (NRM). Many men, mainly those confined in IDP camps) resorted to heavy alcohol consumption to the detriment of their families. They had no time to participate in conflict resolution and peace building.

Raising voices of women and children

The research findings further show that women actively advocate for children’s rights. Pressure for the release of children abducted by the Rebel (LRA) came mainly from women who sometimes risked their own lives in order to pursue children in the bush. Individuals like Comboni’s Sister Rachael, who was then the Head teacher of St. Mary’s College Aboke; in what now Oyam District was case in point. Other examples include women like Angelina Atyam, co-founder of Concern Parent’s Association and Geraldine Onguti co-founder of GUSCCO an NGO. Many women died in attacks because they struggled with the abductors of their children (Burnett and Bede, 2016).

Perception of the Juba peace process

From the study, women were eager to participate in the conflict resolution processes although not all of them were certain of the expected results. Public expectations for peace were overwhelmingly high. Many the respondents hoped for a peaceful future in northern Uganda. To some participants, the general feeling was that the 21 year old conflict would end and peace would return to northern Uganda. However, some others expressed pessimism regarding the Juba peace talks, referring to the talks as fiasco, a game, or a joke. Others said it was a waste of time primarily for people to get monetary benefits, based on past experience of failed peace talks. In interviews carried out Gulu Municipality, 23rd October 2006, one respondent from Gulu Municipality, for example, noted that people were receiving a lot of money from the process and this is why they were delaying to conclude a peace agreement. It was alleged that they were getting over USD $ 200 per day while the people continue to suffer. Some other participants observed that in as far as the International Criminal Court (ICC) upheld arrest warrants against the five indicted rebel leaders including Joseph Kony, the rebel leader would not sign any peace agreement and the whole process would become a total waste of time. As a matter of fact Joseph Kony declined to sign the peace agreement and the whole peace process collapsed dismally.

There was a consensus that women should sufficiently engage in the peace process so as to articulate women’s concerns and thereby influence the final outcome of the negotiation process. Respondents indicated that women with grassroots experience would generously and significantly play big roles in the peace process because of their commitment to peace. The inclusion of ideas and views of grassroots women from Northern Uganda in the Juba peace process objectively would influence the final outcomes of the negotiation with workable solutions since they would be involved in the implementation of the final peace accord. The Juba peace talks were critical to the people of northern Uganda, particularly the many women struggling to survive throughout the sub region. Therefore, it was necessary for the affected people to know of what is taking place in Juba, and how they are being represented in the peace negotiations.

Many respondents were unclear about what was taking place in Juba, due to limited access to information suggesting a serious lack of sensitization, meaning lack of awareness and inadequate information of communities about the peace process that was of national and regional importance. From the findings, different respondents indicated that they had limited direct access to media especially radios in the (IDP) camps.

Sometimes, they listened to radio programs which at times included rebels phoning in. The radios comprised of Mega FM 102’s (Gulu) on “Duogo cen paco” program, meaning return home. While Unity FM on Yabo wangi meaning open your eyes targeted rebels to embrace option for peace as well as talk shows from the Acholi Religious leaders. Access to television was unthinkable and radio access was limited. As people were largely concerned about food and political security, who could waste limited cash on purchasing newspapers in the war zone.

The general lack of information aside, some respondents (59%) expressed total ignorance on what role women played in Juba. The few women like Santa Okot and Betty Amongin, Women Members of Parliament, and former state minister Betty Aketch, were relegated to roles of observers. These women did not participate in the core discussions of the negotiation process. The study also found out that women personalities like Betty Atuku Bigombe who was very familiar with the conflict, were conspicuously absent in national peace processes such as the Juba peace talks although they were instrumental in earlier negotiation efforts before commencement of the Juba talks. These women had abilities and skills except that they were not given opportunities to actively participate in the formal peace process. During the study, one female respondent explained the non-participation of women saying that:

“The reasons why women are not involved stemmed from our cultural influences. Women were always relegated to roles of observers. When issues are still very tough, men say it still risky for women to go to Southern Sudan. Again how could women be involved yet we were in camps? We were here yet they talk of Sudan. Women are not involved because these are things done by high level leaders only, how can we go to Juba and where do we leave our children?”

The voice of the woman in the quote above highlights hindrances to women lack of participation in the official conflict resolution and peacemaking. The obstacles ranged from negative cultural practices, to lack of skills to parental challenges although she did not express how the mentioned challenges were to be overcome.

Women’s need for involvement in peace building processes

From the study, it is clear that the involvement of women in a more formal process such as the Juba peace Talks remained minute. Majority of the people (60%) expressed the need for training, adult literacy programs and exposure to overcome women’s low levels of literacy in order to get the necessary skills in peace building, thereby enabling them to articulate their concerns beyond the family or community levels. Throughout the study, viewpoints were advanced in favor of women’s increased involvement in formal peace building process although (3.3%) still held the perception that women wanted to be involved in the peace process simply for the sake of gender balance. The findings revealed that women genuinely needed to participate in peace building activities. Furthermore, there are a number of other issues that specifically underscored the fundamental need for women’s involvement. Some of them are noted below.

In the first place, it is their constitutional right. According to Uganda 1995 Constitution, the state shall ensure gender balance and fair representation of marginalized groups. It is only women who can best articulate their concerns to the negotiating parties instead of those purporting to represent their needs and views.

The study demonstrated that in course of the 21-year long war, women were primary victims or survivors. Santoshini (2018) re-affirmed the views shared by the respondents when she said that Northern Uganda had the highest rate of post-traumatic stress (54%) and depression (67%) ever recorded among displaced and conflict-affected populations anywhere in the world. She maintained that those women in conflict affected areas were twice as likely to show symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and four times as likely to have symptoms of depression. Santoshini’s observation lent support to the views expressed by many respondents who argued that right from beginning of the conflict, women squarely carried the difficult responsibility of protecting their husbands and children. Women witnessed abductions, killings, and maiming and desertions because of the war. They were vulnerable to rape, and domestic violence and defilement believed to be rampant. As matter of fact, women faced physical and psychological disabilities as well as abject poverty while others were abandoned by their husbands for urban women. One of the respondents, Sylvia Okello Opio, summarized the plight and resilience of women of Northern Uganda as follows saying that: “Women continue to struggle to sustain life. They look for food and provide psychosocial support and hope to the men and children. Others die as try to find their lost ones and some food for their children in the bush.” From the quote, women were tired of suffering and were desperate for peace due to the numerous challenges discussed in this research. The direct participation in the peace process would increase northern women’s prospects of influencing events and issues concerning them in the future.

In the third place, at least 14% of informants referred to the fact that women, as mothers, have a specific role to play in the pacification of northern Uganda. Given the nature of the LRA conflict, women were mothers in the proverbial and liberal senses, both to the rebels and to those at home. As articulated by the women, it is possible for the opposing parties especially LRA to heed to their cries as mothers to quit hostilities and come home. Therefore, the mothers pleaded with their children, including Joseph Kony himself, to come home. Accordingly, many rebels who were forcefully conscripted surrendered (New Vision Newspaper, 2006 October 25th). About 10% of the respondents referred to the fact that unlike men, who tend to be driven by more egoistic tendencies and protection of their masculinity, women were more ready to apologize and much more willing to forgive. Thus, they advocated for use of traditional justice system to be implemented to facilitate the reintegration process of ex-combatants and returnees to their local villages and communities.

Strategies for improving women’s participation

The research highlighted a number of practical approaches/strategies that could promote the involvement of women in conflict resolution and peace building.

Skills development to empower women programs

According to many respondents, women were not involved in the peace process because of low levels of literacy as mentioned earlier. They proposed the need for skills development in peace building perhaps through adult literacy and training programs as well as exposure to enable women to articulate their concerns beyond the family and community.

Building women’s leadership skills

More women need to be encouraged to take on leadership positions and their skills built for effective representation. This would enable them to participate beyond the household level and ensure their effective participation in conflict resolution and peace building. Also, the roles played by women at the grassroots level in peace building should be rewarded to build grassroots leadership capacity and confidence as motivation for the work that for long was unrecognized.

Support women’s initiatives and numerical increase in participating in public sphere

There was concern that women’s efforts need to be better supported, in particular small women’s groups operating at the grassroots. While some deliberate action was taking place, for instance, the formation of groups such as, Telela IDP, imatiyamaluoryeler meaning old mothers stand up and stretch the muscles was a means of strengthening confidence and promoting collective action for conflict resolution, such activity remained largely unrecognized, thereby undermining its full potential. For instance, women artists, as mentioned above, could be specifically supported. Furthermore, women need to seek better representation both in employment structures and positions in cultural institutions so that their views can be represented at decision-making levels. As the research revealed, women were not actively engaged in any serious way in the Juba peace process and other structural peace building processes.

Peace promotion at the grassroots level

There is need to strengthen the existing peace efforts at the grassroots level by sharing lessons learnt from different communities. Women peace activist at the grassroots level should be supported to improve the effectiveness of their interventions and to share their experience with others.

Creating a forum for women to voice their views

The study found out that although women had diverse issues and proposals to voice, they did not have suitable fora to present their ideas since they were left out from various conflict resolution activities. Specifically, they were generally given inadequate space to articulate themselves in meetings. Efforts should also be made to create more spaces for grassroots women to participate in peace processes through strengthening the linkages between less educated rural women in northern Uganda with their more exposed and literate peace activists in urban areas.

Perceptions of people about resolution

One of the objectives of the study was find out people’s perception about Resolution 1325. The study revealed that perceptions of majority of women (80%) of grassroots women expressed lack of awareness of the Resolution 1325. The lack of awareness of Resolution 1325 was compounded by the lack of Peace Research such as those conducted by Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) in Norway, Kenya, Rwanda etc whose dissemination of results would have created need for sensitization for awareness creation in the conflict region of northern Uganda. Even as the Resolution recognizes the importance of increasing women’s participation in peace building, conflict and post conflict reconstruction processes as well as supporting women’s peace initiatives, gender violence remains high in Northern Uganda. Although the UN Security Council Resolution 1325 was viewed by many as bench mark because, for the first time ever, it recognized the needs, rights, and experiences of women and girls in armed conflict, peace,

and Security Sanam (2007), noted that the Resolution 1325 had little or no impact on the women. At the time of this research, Northern Ugandan women and majority (99.9%) of Ugandans lacked awareness of the resolution 1325 though the situation was slowly changing. The study notes that the lack of knowledge of the Resolution by the expected beneficiaries defeats the purpose of the R 1325.

Women’s conspicuousness in conflict mitigation/ resolution and peace building

Although the lack of women’s Conspicuousness in conflict resolution and peace building in Northern Uganda derive from cultural influences to some extent, the study argues that it is not just a matter of patriarchal influences in Ugandan societies, but also the interplay of multiple factors. Few women about (5%) are now venturing into high level political and socio-economic participation. However, majority of women (80%) lag behind due to lack or limited public exposure necessary for changing perceptions and mindset, rampant low levels of literacy compounded the cultural influences and low level of literacy. The literacy rate in Uganda measures at 65%. Majority of the 35 % who are illiterate are women. Therefore the study argues that women’s limited educational skills relegate them to the periphery of society making it difficult for them to participate in decision making, hence their exclusion in the formal peace processes. However women’s low levels of literacy should not be viewed as a permanent situation. This problem is being addressed by government and other actors. There are many affirmative action programs are being rolled out by government in combination with others development partners such as NGOs to target women in education; business, agriculture as well as politics. This is source of hope for transformation.

Further, the study clarified where women’s lack of conspicuousness was visible in the arena of conflict resolution and peace building and also boldly demonstrates the level of women’s conspicuousness especially at grassroots level. In northern Uganda, there perhaps only 1-2% of women have been peace negotiators, at the official peace building processes such as the Peace talks in Juba back in 2006, women representation was unmistaken missing. Therefore it can be argued that at the national levels of decision making and participation in peace building and conflict mitigation and resolution, women were conspicuously absent. However at the grassroots level, women were active participants in the peace processes and conflict resolution and mitigation.

Therefore, the research concluded that the roles women play in society especially in pacification of conflict ravaged areas, can no longer be ignored, discounted or undermined. In the context of in Northern Uganda, women played an important role in promoting conflict mitigation and resolution through a variety of different grassroots strategies. Although women were conspicuously absent at the national level (formal) peace processes, their contributions to the peace building were significant both as individuals and groups in the lower levels of Uganda society. In as far as the potential roles of women in conflict are not duly recognized and appreciated, their skills, knowledge and contributions shall continue to be underutilized. As the findings revealed women and children particularly bore the brunt of the conflict and were exhausted with warfare. The best option for promoting this need in the future should be to consult women in order that they participate directly at both national and grassroots levels. In this study, 80% of women asserted that the political field was and is still not level as political and economic arenas are still male dominated.

The United Nation Resolution 1325 driven by the desire to see a fair just and inclusive society in which women’s voices could be heard and their contributions recognized is critical for women’s active participation in security and peace building. Women did not fail to strategically use their identities as mothers and care givers, which in effect influenced negotiations in favor of peace and reconciliation. They did all that despite the understanding that living and operating in patriarchal society such as Uganda, women were generally restricted from speaking out publicly, hence their lack self-confidence and self-esteem. The lack of awareness of UN Resolution 1325 by women as the primary beneficiaries of the resolution (on women, peace and security) was manifest in their exclusion in the official peace processes in Northern Uganda. Perhaps if known and implemented, Resolution 1325 could greatly empower and transform women’s lives with specific reference to peace building and post conflict reconstruction. The study concludes that although women were conspicuously absent in peace building processes at the national level, at the grassroots levels women in northern Uganda, ably identified and articulated numerous bottlenecks to their active participation in the peace processes.

In relation to the research findings, recommendations were made to the protagonists in the conflict on critical issues conflict mitigation, prevention and peace building in context of the UN Resolution 1325.

Promotion of peace and resolution 1325

(i) From the research it is apparent that peace is an imperative in northern Uganda. The government should demonstrate total commitment to the cause of peace. Furthermore, given that it is the people of northern Uganda and women in particular, who are the primary losers in the conflict, the government needed to facilitate the rebels to meet the people they wronged including women to dialogue on critical societal issues. This means government needs to invest more in the return of the rule of law so women and men in Northern Uganda enjoy peace, security and well being.

(ii) The Resolution 1325 provides a platform for recognizing and augmenting women’s contribution to sustainable peace and social development. The Resolution admittedly, emphasizes Women, Peace and Security and pushes for effective inclusion of gender perspectives which could meaningfully impact the lives of women, girls, men, and boys. The resolution specifically addresses how women and girls are differentially influenced by conflict and war, while recognizing the critical role that they can and are already playing in peace building efforts. Most importantly, the UNSCR 1325 recognized that peace and security efforts are more sustainable when women are considered and treated as equal partners in the prevention of violent conflict as well as the delivery of relief and recovery efforts and in the building lasting peace. Without peace, there can be no conducive environment for implementation of Resolution 1325 which means women would lose out on the benefits of the Resolution

(iii) Uganda has been a United Nations member country and signatory to many UN conventions including Resolution 1325, which was adopted in October 2000 since independence 1962. This means that the Uganda government has responsibility and duty to implement Resolution 1325. Therefore there is need for government to make concerted efforts towards operationalization of Resolution 1325. For example, through formulation and enhancement of existing gender focused policies and supporting initiatives by both state agencies and civil society organizations to increase civic sensitization levels of both rural and urban communities. This is because Resolution 1325 is very relevant to women’s empower-ment and recognition of the significant roles they play in community development and peace building at all levels.

Long term strategies

(i) Problems of regional imbalances in development and corruption continue to haunt Uganda and should be addressed with regard to the country as a whole and with specific reference to Northern Uganda which has lagged behind for over two decades. Even as, the preconditions of war in the North are identical to those of other regions of Uganda, the peace process should comprehensively address the causes of conflict holistically so that both women and men can benefit from post conflict reconstruction programmes.

(ii) There is a general need to develop women’s leadership skills. More women need to be encouraged to train to acquire leadership skills so that they can effectively represent their constituencies. Specifically local women leaders, like their male counterparts, need a forum in which to discuss pertinent issues arising from the nature, state, and magnitude and spiral build of the conflict in northern Uganda.

(iii) One of the major reasons for lack of women’s involvement in the peace processes was the low levels of education. Therefore, it is important that women’s education is deliberately promoted which should involve a dramatic increase in adult literacy programs in the post conflict era.

(iv) There is a great need for more research that documents and publishes the numerous roles of women in conflict and post conflict situations in northern Uganda, the rest of Africa and elsewhere in the world.

(v) As the conflict in northern Uganda ebbs, it is imperative that mechanisms for conflict resolutions and mitigation such as truth, justice and reconciliation commission be established to enhance the process of national healing through reconciliation and administration of social justice thereby ensuring sustainable peace.

(vi) The international community has a role to play in negotiating with the International Criminal Court (ICC) on what constitutes justice in the northern Uganda context. With specific reference to the trial of Dominic Ongwen, one of the former rebel leaders, by the ICC, the outcomes at The Hague should culminate in a win-win situation for all parties involved. It should be noted that by 2019, that trial of the Dominic Ongwen, is still ongoing.

(vii) The study encourages the international community to recognize that people in the Northern Uganda are deeply concerned about the need for long term reconciliation and national healing. Therefore, any reconstruction programme within the region and indeed the wider strategy must of necessity include promotion of reconciliation within the region and indeed, the whole country. This can be done in part through supporting civil society groups on the ground and encouraging links between reconstruction and reconciliation activities.

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Andrabi S (2019). New Wars, New Victimhood, and New Ways of Overcoming It. Available at

View.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Angom S (2018). Women in Peacemaking and Peace building in

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Northern Uganda. Available at

View

|

|

|

|

|

Burnett M, Shepard B (2016). Remembering the Wisdom of Uganda's Aboke Girls, 20 Years Later.

|

|

|

|

|

Constanza YOC (2016). Empowerment of Women during Conflict and Post-Conflict Phases and the Role of Humanitarian Aid Organizations in Supporting Women's Newfound Empowerment Gained during Conflict.

|

|

|

|

|

Government of Uganda (1995). The Constitution of the Republic of Uganda, Kampala.

|

|

|

|

|

Hovil L, Lomo ZA (2015). Forced Displacement and the Crisis of Citizenship in Africa's Great Lakes Region: Rethinking Refugee Protection and Durable Solutions. Refuge: Canada's Journal on Refugees 31(2):39-50.

|

|

|

|

|

Justice and Reconciliation Project Special Issue with Quaker Peace and Social Witness (QPSW) (2008). With or Without Peace: Disarmament, Demobilization and Re-integration in Northern Uganda. Available at

View

|

|

|

|

|

Kimotho J (2017).The role of education for women and girls in conflict and post-conflict countries. Available at

View

|

|

|

|

|

Musinguzi D (2019). The Role of Civil Society Organizations in Post-Conflict Development of Northern Uganda. Available at

View.

|

|

|

|

|

Nkosazana DZ (2013). Women, Men, Armed Conflicts and Peace building.

|

|

|

|

|

Okiror S (2016. How the LRA still haunts northern Uganda. Available at

View

|

|

|

|

|

Ramšak A (2015). United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325: Women, Peace and Security in the countries of Western Balkans and Slovenia. Available at

View

|

|

|

|

|

Roslyn W, Applebaum A, Rodham H, Fuhrman H, Mawby B (2017). Women's Peace building Strategies Amidst Conflict: Lessons from Myanmar and Ukraine. Available at

View

|

|

|

|

|

Sakuntala B (2019. Women as Constitution makers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Sanam NA (2007). Women Building Peace: What They Do, Why It Matters. Boulder, CO: USA. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

|

|

|

|

|

Sanam NA (2016). Women Build Peace' But Their Voices and Stories Have Been Ignored. Available in

View

|

|