ABSTRACT

This research study, aims to examine the influence that an intervention program based on the Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility (TPSR) model and the multidimensional approach to sportsmanship has on middle school students. Researchers focused on the detection and examination of improvements on students’ sportsmanship awareness and contributions to their moral and character development. Participants were 90 middle school students aged between 11 and 13 years old, who received five structured lessons and a review session following the TPSR model. The sample was evenly split by gender (44 males, 44 females, 2 not declared). The Sportsmanship Awareness Questionnaire (SAQ) was administered before and after the intervention. The teacher in charge of implementing the program was purposefully selected and trained. Results showed a statistically significant improvement in the students’ sportsmanship awareness scores for the entire sample and for each grade level. Results also indicate female participants scored notably higher than males on both questionnaires. The approach used for this study provides novel instrumentation to objectively assess sportsmanship constructs with consistent validity and reliability. The findings obtained from this study confirm the efficacy of intervention programs such as TPSR to achieve student moral and character development at the middle school level. The implications of this study and future directions for research in TPSR are discussed.

Key words: Sportsmanship, physical education, teaching personal and social responsibility model (TPSR), school-based intervention programs.

Whether or not participating in sports builds students’ character is an ongoing debate. The debate begins at the onset of trying to define character. Unfortunately, the meaning of character is a conundrum across the fields of psychology, sports, and education. Character is the inner dimensions of a person in which the processes of moral action become one’s behavior (Shields and Bredemeier, 1995), or simply the sum of a person’s moral qualities (Brody and Siegel, 1992). Grappling with definitions further convolutes the encompassing aspects of character education, goals of character education, and developing adequate measures for assessing character education.

Despite debate, Berkowitz and Hoppe (2009) define character education as deliberate attempts to promote the development of student character and its features (empathy, compassion, moral sensitivity, etc.) in schools. Doty (2006) posits that positive character traits may be developed through sporting experiences as long as coaches, teachers and administrators consciously make character development an outcome of the activity. Arguably, a conscious effort leaves much to the imagination as to how teachers can implement effective character education programs in the physical education classroom.

An argument can be made that character education is best when underpinned by the blending of children’s competitiveness and their moral development demonstrated through sportsmanship acts (Goldstein and Iso-Ahola, 2006). Moral development is a product of the internalization process of modeled and reinforced behaviors from significant adults, such as parents, coaches, teachers, and peers (Bandura, 1986). Studies support the claim that the moral development is dependent upon cognitive development (Mouratidou et al., 2007; Shields et al., 2007; Schwamberger and Curtner-Smith, 2019). In the field of physical education, sportsmanship promotion is considered a key component for achieving the development of students’ moral and ethical domain (Burgueño and Medina-Casaubón, 2020).

Sportsmanship is considered to be a broad concept; one of the most commonly used theories to approach it is the one outlined by Vallerand et al. (1996) based on social psychological theories and research, that defines sportsmanship as a multidimensional construct built of five factors corresponding to the respect and concern for: “one's full commitment toward sport participation; the rules and officials; social conventions; the opponent; negative approach toward sport participation” (Vallerand et al., 1996). Other researchers such as Hellison (2011), developed the “Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility” model (TPSR); a pattern of instruction for sportsmanship in schools, consisting on the development of personal and social responsibility in terms of respecting the rights and feelings of others, effort and cooperation, self-direction, helping others, leadership, as well as the transference of these traits outside the gym (Hellison, 2011). Extensive research has been conducted on finding the definition and delimitations of the concept of sportsmanship (Beller and Stoll, 1993; Goldstein and Iso-Ahola, 2006; Vallerand et al., 1996) and different models for applying it into the educational setting (Burgueño and Medina-Casaubón, 2020; Giebink and McKenzie, 1985). Resulting from numerous studies that have described and developed the concept of sportsmanship, scholars now have the opportunity to examine “Do sports build character?” (Doty, 2006).

The purpose of the present study was to examine middle-level students (11-13 year olds) perceptions of sportsmanship upon considering real life situations that involve a moral dilemma in sport environments. In each situation presented, students must make use of their notions on morality to resolve them. Students then reevaluate their positions to each situation after a specific teaching intervention with the hope that students are better equipped to employ empathy and ethical values to address these scenarios. This research study attempts to deliver a purposeful intervention based on the “Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility” model designed by Hellison (2011) and the multidimensional approach to sportsmanship proposed by Vallerand et al. (1996) with the intention of improving sportsmanship awareness among middle school students and contributing to their moral and character development. This study contributes valuable insight into a successful implementation of explicit, sportsmanship- based, deliberate instruction as a vehicle for improving students’ moral development (Schwamberger and Curtner-Smith, 2019). For this study, the researchers conducted modifications on the Multidimensional Sportspersonship Orientations Scale (MSOS) (Vallerand et al., 1997), based on Dunn and Dunn’s (1999) article, with the purpose of adjusting it to scenarios in which moral dilemmas are displayed in settings such as school or sport activities that can frequently present to the students (Schwamberger and Curtner-Smith, 2017).

The resulting instrument of this study (Appendix A: Tables 1 to 6), together with the results obtained from this research, may be utilized to develop and improve implementation models that promote moral development in schools. Exploring the efficacy of the application of purposeful programs, that include an explicit dialogue about sportsmanship and values with the students, may provide a source of valuable information for educational leaders. In the literature review presented in the following section, the history of the context of sportsmanship, as well as the different possible definitions of the concept and the models designed for its implementation in schools are analyzed and displayed in relation to the research lines of the study.

Keating (1964) established a pathway toward an initial understanding of sportsmanship, referring to this concept as a conduct flowing from one’s attitudes. Keating dedicated special attention to the core virtues that characterize the attitudes of a well behaved athlete, opening a new line of research for the rest of scholars. A line that researchers such as Vallerand et al. (1996) followed adopting an approach to sportsmanship that directs the scope toward the social concern, rather than the justice focused procedures that other scholars presented (Shields and Bredemeier, 1986). Vallerand and colleagues (1996) put the focus on the interpersonal aspect of sportsmanship, studying the attitudes that are present in interactions between the different participants that take part in sport activities (players, coaches, referees, etc) with the intention of finding an ecologically valid definition interpreting the nature of sportsmanship as a multidimensional concept instead of a largely unidimensional construct. In consequence of this new definition, Vallerand et al. (1997) developed and validated an original instrument for the measurement of sportsmanship based on previous research on morality (Quinn et al., 1994).

The Multidimensional Sportspersonship Orientations Scale (MSOS) (Vallerand et al., 1997) is an instrument in which each of the dimensions of sportsmanship was addressed by asking subjects’ perceptions of morality that could be registered by rating behaviors and attitudes presented in naturally occurring sport related situations. Both the multidimensional definition of sportsmanship and the MSOS instrument resulted to be highly influential for the researchers in this current study at the time of addressing and evaluating sportsmanship among participants.

As sportsmanship promotion became a key curricular component in physical education (Burgueño and Medina-Casaubón, 2020), multiple intervention programs such as Sports Education (Siedentop et al., 2019) or Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility (TPSR) (Hellison, 2011) were designed for their application in schools. Studies related to these interventions demonstrated improvements in the social category of physical education and sports (Hastie, 1998). Authors exploring the Sports Education (SE) intervention observed that students emphasized teamwork and cooperation during the intervention, demonstrating acceptance and respect for others throughout their actions (Carlson and Hastie, 1997). In further SE studies, researchers found that there was a positive impact in the students’ social skills and values related to empathy, fair play, and assertiveness (Evangelio et al., 2018).

In relation to the Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility (TPSR) model, research reflected significant increase in self-regulatory efficacy and responsibility behaviors by the students as a result of the intervention (Escartí et al., 2010). In addition, the implementation of the TPSR model generated a positive effect in language awareness among students as they displayed more respectful communication with teachers and peers (Filiz, 2017). The TPSR model is considered to be a purposeful intervention program consisting on the integration of strategies for the development of responsibility among students that promote attitudes and behaviors that benefit the thrift of oneself and others in their respective social environments. The researchers in this current study found in Hellison’s approach an opportunity for the development of morality and responsibility among students addressing the different dimensions of sportsmanship described by Vallerand et al. (1996). The adjustability of the TPSR model to the different dimensions of sportsmanship led the researchers in this study to develop an intervention program that allowed them to hypothesize a possible significant increase in the results from the initial sportsmanship notion of mid-level students and the results obtained after the implementation of the development model.

Research design

This quantitative study was conducted using a quasi-experimental research design. A nonequivalent control group design, more specifically, a one group pretest- posttest design was utilized in this study. Descriptive statistics were utilized to ensure that the data was normally distributed. SPSS was used to analyze the data.

Participants

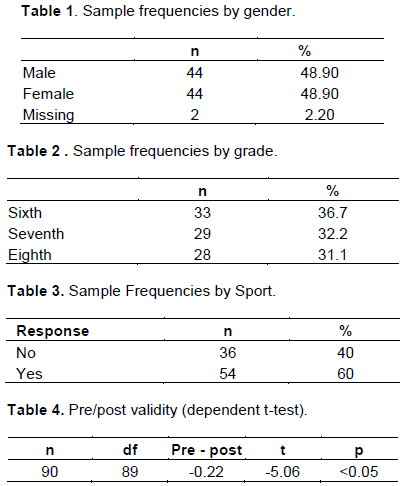

The participants that took part in this study were 90 American middle level students (males n = 44, females n = 44, missing n = 2) aged between 11 and 13 years old belonging to sixth, seventh and eighth grade classes from a middle school located in central Missouri, United States. All children in each class were asked to participate. Sixty percent of the sample (n = 54) reported being involved in competitive sports, while forty percent of the students (n = 36) did not participate in sports. None of the students had previous experience with a Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility curriculum. The teacher and students were purposefully selected. The teacher was trained on the delivery and analysis of the TPSR model. The purposive sample provided the means to analyze the effect of a sportsmanship intervention program on mid-level students attending a public school that never received this kind of intervention prior to this study.

Instrumentation

Based on the findings that Vallerand et al. (1997) presented in the validation process of the MSOS instrument, the pre-test that was administered to the students consisted on a questionnaire that apprehended the different dimensions of the sportsmanship definition presented by the researchers. This questionnaire, named Sportsmanship Awareness Questionnaire (SAQ), was composed of five open-ended scenarios addressing each of the five sportsmanship dimensions, corresponding to respect for full commitment towards sport participation; the rules and officials; social conventions; the opponent; negative approach toward sport participation. Each of the dimensions, embodied five behavior aspects belonging to the construction of that dimension of sportsmanship, making a total sum of 25 aspects (five per component) (Vallerand et al.,1997). The scenarios were vetted with the collaboration of professionals in the fields of education and sports. This instrument measured students’ sportsmanship knowledge prior to the intervention and after the instructional intervention. For each of the answers that the students presented in relation to the scenarios, researchers identified the number of dimension aspects present in the student’s answer to the scenario that targeted specifically a particular dimension of sportsmanship. In order to advance in this identification process, the researchers developed a coding rubric that allowed them to detect the different dimension aspects within the students’ wording. Once the researchers could recognize the amount of dimension aspects included in that student’s answer, they could give a score to it. The scores were assigned based on a rubric designed by the researchers and organized in the scales of naïve answer (level 1), mixed answer (level 2) and informed answer (level 3). Level 1 of this rubric corresponded to answers in which between 0 and 1 dimension aspects were included. Level 2 alluded to answers in which between 2 and 3 dimension aspects were present. Level 3 was designated to answers where the students incorporated between 4 and 5 dimension aspects. Prior to data analysis, inter-rater reliability was determined whereby three independent researchers scored five surveys (a total of 15 items) independently. The variable “sportsmanship” consisted of 5-items. Each scorer independently utilized the developed rubrics and reported 100% agreement among all 15 items among three identical surveys. Additionally, Cronbach’s Alpha statistic (Table 4) for the five-item instrument was internally consistent for both the pre- test (α = 0.78, acceptable; α = 0.84; good). To further substantiate the reliability of the instrument, the Pearson correlation was significant for each item from pre-test to post test, and there was a significant correlation for the variable “sportsmanship” between the pre-test scores and post-test scores (r = 0.61, p<0.05).

Data collection

This study occurred in three different phases consisting of a pre-intervention administration of the Sportsmanship Awareness Questionnaire (SAQ), the implementation of the Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility model, and a post- intervention measure accomplished by the application of the SAQ.

The first phase of procedures included the introduction and delivery of the SAQ survey to the students. The questionnaire, composed of five open-ended scenarios addressing each of the sportsmanship dimensions, was administered to students through an online survey utilizing web-based technology. Participants completed the questionnaire in the school campus during class hours and they were given an unlimited amount of time to answer the scenarios. Once the students completed the online survey and the answers were submitted for processing, the results were automatically saved into an online database. The second phase was centered on the instructional period, consisting in the implementation of the TPSR program at the school. The Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility model is an instructional approach developed through more than 30 years of research and experience which purpose is teaching kids to develop personal and social responsibility through physical activity and transfer these ideas to other areas of life (Hellison, 2011). The implementation of this model, considered to be one of the most distinguished instructional approaches in physical education pedagogy (Wright et al., 2010), implies a process of values orientation that promotes human decency and positive relationships with others as core pillars (Hellison, 2011). An essential component of Hellison’s TSPR theory is the designation of five different levels of responsibility consisting of respecting the rights and feelings of others, effort and cooperation, self-direction, helping others and leadership, and transfer outside the gym. This program is implemented in the field through a specific lesson plan structure that includes relational time, awareness talk, physical activity plan, group meeting, and self-reflection time. The research team in this study decided to connect the multidimensional concept of sportsmanship (Vallerand et al., 1997) with the TPSR instructional model (Hellison, 2011) with the intention of elaborating an approach for the development of sportsmanship awareness in mid-level students. In order to achieve this purpose, the researchers put into practice an instructional program composed of five structured lessons and a review session. Each of the five lessons were designed based on specific TPSR learning objectives and implementation strategies that targeted an express responsibility level linked with a particular dimension of sportsmanship (Appendix B). As a review session, students led a discussion in which they debated the main ideas and facts to be remembered that they considered important after participating in activities of the five previous lessons.

During these five sessions, the students were engaged in group and individual activities that involved participants taking on roles of responsibility, conflict resolution situations, decision making processes and goal setting proceedings, through which they explored different circumstances, related to human interaction that they later discussed through structured debates at the end of the lesson. The third phase focused on the administration of the SAQ survey following the same procedures as the first phase, with the intention of realizing a comparative analysis between the data from pre and post intervention.

Demographics

The sample was evenly split by gender (Table 1) where the majority of students were in sixth grade (11 years old) and participated in a competitive sport (Tables 2 and 3). The sixth grade sample consisted of 19 males and 13 females; seventh grade, whereas the majority of the seventh and eighth grade samples were female (15 and 16 females respectively). However, there was no statistically significant difference in the frequency of students among grade levels by gender, [X2(2) = 1.84, p >0.05].

Sixty percent of the sample reported playing a competitive sport (Table 3); however, there was no statically significant difference in the frequency of students among grade levels by those who indicated they did or did not participate a competitive sport, [ X2(2) = 1.52, p >0.05]. Further, but insignificant findings showed that more seventh graders (age 12) were involved in competitive sports compared to sixth or eighth graders. The exact same number of males and females in the sample (n = 27 or 61.36%) indicated that they played in a competitive sport. The analyses of the demographics suggest that there are no key demographic differences in the frequencies of gender or involvement in a competitive sport among the grade levels.

Instrument analysis

Prior to data analysis, inter-rater reliability was determined whereby three independent researchers scored five surveys (a total of 15 items) independently. The variable “sportsmanship” consisted of 5-items. Each scorer independently utilized the developed rubric and reported 100% agreement among all 15 items among five identical surveys. Additionally, Cronbach’s Alpha statistic (Table 4) for the five-item instrument was internally consistent for both the pre-test (α = 0.78, acceptable; α = 0.84; good). To further substantiate the reliability of the instrument, the Pearson correlation was significant for each item from pre-test to post test, and there was a significant correlation for the variable “sportsmanship” between the pre-test scores and post-test scores (r = 0.61, p<0.05).

The validity of the construct “sportsmanship” was determined by an overall increase in sportsmanship scores from pre-test to post-test. If an instrument is valid, then a purposeful intervention targeting change in the construct would occur over time. There was a significant increase from pre-test to post-test sportsmanship scores due to a purposeful intervention. The post-test scores were on average 0.22 higher than the pre-test (Table 5). Finally, content validity of the instrument is supported by significant Pearson correlations among the five post-test sportsmanship items (Table 6). The correlations are not strong enough to convincingly establish convergent validity; however, since each item targets very distinctive (different) aspects of sportsmanship, significant correlations were expected to be at or near 0.50 for establishing convergent validity. The significant, moderate correlations among items indicate the expected breadth of the sportsmanship construct. Nevertheless, the significant pre- to post- test changes indicates that while the construct is broad, the instrument is internally valid for purposes of measuring sportsmanship [t (89)=-5.06, p <.05].

Descriptive statistics

The mean sportsmanship score, identified in Tables 6 and 7 as PRE_Ave and POST_Ave. were 1.57 and 1.79 respectively. The scores were treated as interval data since the scoring rubric provided equidistant criteria for scoring among the three levels of naïve, mixed, and informed (each level represented a number of aspects present). The variance, skew, and kurtosis are acceptable among the pre-intervention items, among the post-intervention items, and the variances between PRE_Ave. and POST_Ave. were not significantly different. A linear relationship between observed cumulative function and the theoretical cumulative function supports that the PRE_Ave and POST_Ave sportsmanship scores were normally distributed. A slight positive skew of 1.2 was found for item number two of the pre-test, labeled PRE_Q2; however, this did not drastically affect the overall skew of PRE_Ave. for the entire sample (Table 6). Descriptive statistics were also calculated by grade, gender, and whether students were involved in a competitive sport (Table 7).

Table 6 data were graphed to visualize pre- and post- sportsmanship scores by group (Figures 1 to 3). It was apparent that instruction had a significant positive impact overall; however, some subgroups, such as sixth grade males and females that participated in sports (Figure 1) showed the greatest affect from instruction given large increases from pre- to post- test scores. Figures 1 and 3 indicate that there might be differences in mean sportsmanship scores by gender. Figure 2 provides some evidence that seventh grade males who do not compete in a sport had similar mean sportsmanship scores as seventh grade females that participated in a sport; however, only three individuals comprised the seventh grade, male, and no sport subgroup (Table 7).

Column graphs were created to visualize and compare the change in mean sportsmanship scores from pre- to post- test by subgroup (Figure 4). Students, regardless of gender or grade, who participated in sports, had a mean increase of 0.24 in sportsmanship scores compared to the mean increase of 0.19 for the students who did not participate in sports.

When comparing pre- to post- test change statistics taking only grade level into account, seventh grade students exhibited the greatest increase (0.26) compared to sixth (0.21) and eighth grade (0.18) groups.

Inferential statistics

Table 5 displays the results from a dependent t-test indicating that for the entire sample there was a statistically significant increase from pre- to post-test mean sportsmanship scores. A between males and females with an independent t-test showed female’s mean sportsmanship scores to be higher than males [pre: t (86) = 4.06, p < 0.05; post: t (86) = 3.03, p < 0.05]. Variances between male and female sportsmanship scores were not significantly different. Dependent t-tests determined there was a statistically significant increase from pre- to post- sportsmanship scores for males [t (43) = 3.69, p < 0.05] and females [t (43) = 3.17, p < 0.05].

There was no statistically significant difference in pre- or post- mean sportsmanship scores among grade levels. A one-way analysis of variance found comparisons among grade levels was not significant when comparing just pre-test scores or post-test scores among grade levels: pre [F (2, 89) = 1.69]; and post [F (2, 89) = 1.32]. Additional dependent t-tests determined positive, statistically significant change from pre- to post- sportsmanship scores for each grade level; for the sixth grade group, [t (32) = 2.91, p < 0.05]; seventh grade group, [t (28) = 4.07, p < 0.05]; and eighth grade group, [t (27) = 2.03, p < 0.05].

Mean pre-, post-, and the change in sportsmanship scores were analyzed between students who participated in sports and those who did not. The independent t- test found no statistically significant differences between the two groups for each analysis [pre: t (88) = 0.60, p > 0.05; post: t (88) = 1.00, p > 0.05; change: t (88) = 0.62, p > 0.05]. There was a statistically significant increase in mean sportsmanship score from pre- to post- test for both groups. Students who did not participate in sports showed a mean score increase of 0.19 [t (35) = 2.46, p < 0.05], while students who did participate in sports showed a mean score increase of 0.24 [t (53) = 4.63, p < 0.05].

Further comparisons of pre to post data using the Wilcoxon signed ranks test found significant differences for sixth grade males who competed in competitive sports (Z= -2.5, p = 0.01). The mean sportsmanship scores for this group significantly increased from 1.24 to 1.64. Similarly, there was a significant increase in mean sportsmanship scores for all sixth grade students who played competitive sports (Z= - 2.85, p = 0.00), and all seventh grade students who competed in competitive sports (Z= -2.60, p = 0.01). There was not a statistically significant increase in mean sportsmanship scores for with sixth and seventh grade students who did not compete in competitive sports. Overall findings find that females have higher pre and post mean sportsmanship scores than males; however, the groups that increased the most from pre to post test for measured sportsmanship were sixth and seventh grade students who competed in competitive sports.

The objective of this study was to examine the influence of a moral development program such as the TPSR model on middle-level students’ sportsmanship awareness. In concrete terms, the researchers addressed the possibility of generating a significant difference in the frequency of response level from the students regarding the multidimensional conception of sportsmanship established by Vallerand and colleagues (1997), through the application of purposeful intervention targeting personal and social responsibility.

The first result emerging from this research was that there was a statistically significant increase from pre- to post- test mean sportsmanship scores for the entire sample. These findings confirm the initial hypothesis regarding the TPSR model as an efficacious approach for the development of responsibility and sportsmanship in mid- level students. The relevance of this conclusion leads the researchers to highlight the importance of integrating in schools activities in which students become active participants of situations where moral traits such as empathy, respect, patience, or generosity are included with the intention of generating learning regarding their perception of sportsmanship, as well as of the acts and behaviors that are characteristic of a good sport. While the majority of studies related to models such as TPSR address its implementation in extracurricular settings, there is considerable research still to be made in the school setting (Carbonell, 2012; Compagnone, 1995; DeBusk and Hellison, 1989). The findings obtained from this study extend TPSR and sportsmanship literature by researching the application of the model in the educational setting, adjoining an emerging wave of research (Carbonell, 2012; Gordon et al., 2012; Merino-Barrero et al., 2019; Pan et al., 2019) in the endeavor of developing and examining programs of this nature implemented during school hours.

An important finding presented in this study is the presence of a higher increase in the score difference of students that participate in competitive sports compared to the ones who do not participate in competitive sports. Sixth and seventh grade students that participate in sports registered the biggest increase from pre to post test for measured sportsmanship. At the time of analyzing the possible causes of this difference, it is important to take into account that the TPSR model displays physical education and sports’ situations to generate a reflection in the students that links these scenarios to daily life situations in which they can display responsible behavior (Hellison, 2011). Considering this approach, the authors’ impressions regarding the possible causes of this difference in score increase refer to the significance that the situations displayed in this model originated in the students that participate in sports and the possible effects of these scenarios on the generation of intrinsic motivation among the students. The situations presented in this intervention have been previously witnessed by students that participate in sports at the time of competing, which results in a bigger familiarity and engagement level with these scenarios, leading to the adoption of a task orientation position by the students, and therefore the achievement of meaningful learning through a strong connection with the subject (Schiefele, 1991). Further research is needed in order to determine with exactitude if this type of interventions have a constant higher impact on students that participate in competitive sports.

Another result was that females scored notably higher than males on the sportsmanship pre-test administered prior to the intervention as well as on the post-test completed at the end of the program. These findings parallel conclusions drawn by researchers on the field that analyzed gender and sportsmanlike conducts in physical education and sports settings (Esentürk et al., 2015; Koç, 2017; Koç and Yeniçeri, 2017; Tsai and Fung, 2005), but differ from other studies that observed higher scores for males than females in relation to behavior management (Manzano-Sanchez et al., 2019) or regulation (Burgueño et al., 2020). Further research is needed to clarify and refine conclusions regarding the relationship between gender and sportsmanship; research involving extensive sampling, prolonged intervention programs, and analysis of responsibility, basic psychological needs, and motivation levels among participants (Wright and Burton, 2008).

In relation to age groups, the findings obtained from this study indicate that there was a positive statistically significant change from pre- to post- sportsmanship scores for each grade level. Sixth grade (11 years old), seventh grade (12 years old) and eighth grade (13 years old) groups responded to intervention registering significant improvement regarding sportsmanship awareness level. These findings contribute to TPSR literature by demonstrating the effectiveness of the program in this particular set of grade levels known as mid-level or middle school. The significance of these findings lies on the input of new results regarding the implementation of TPSR in these specific grade levels, given the considerable existence of research, information, and interventional experience from TPSR programs oriented to high school students (Burgueño and Medina-Casaubón, 2020; Manzano-Sanchez et al., 2019; Pan et al., 2019; Wright and Brown, 2008; Wright et al., 2010) compared to the apparent smaller number of studies that oriented the intervention to mid-level age groups (Diedrich, 2014; Escartí et al., 2010b; Filiz, 2017). There is still further research to be made targeting mid-level age groups and considering more variables in order to adapt and design TPSR interventions that generate consistent effectiveness in sportsmanship and character development in students of all levels.

Another important product of this study was a valid and reliable Sportsmanship Awareness Questionnaire (SAQ) instrument, along with coding and scoring rubrics, that can be confidently used for middle level aged students. The SAQ instrument targeted the five dimensions of sportsmanship (Vallerand et al., 1997) through scenarios that result accessible and relatable to mid-level students. If the instrument is valid, then a purposeful intervention targeting change in the construct of sportsmanship would occur over time; this circumstance happened in this research study as students’ performance reflected an overall increase in pre- to post- test scores. Further analysis regarding content validity of the instrument was supported by significant Pearson correlations among the five post-test sportsmanship items. Regarding reliability of the instrument, initial inter-rater reliability was determined by three independent researchers, followed by additional examination through Cronbach’s Alpha statistic analysis, and further review to substantiate the reliability of the instrument represented by significant Pearson correlation for each item from pre- to post- test, and a significant correlation for the variable “sportsmanship” between the pre-test scores and post-test scores.

There is a widespread popular belief that society tends to adopt regarding the relationship between sport activities and character; this conviction refers to the reliance that it is placed on sports to educate individuals in values and morality through situations that expose participants to success, failure, and collaboration circumstances among other experiences. The emergent appearance of studies like this one, that explicitly target factors for moral and character development through sport activities, points this popular belief as a socially accepted misconception, due to the demonstrated need for an explicit conversation and intervention about sportsmanship and character in order to generate an impact in the students. It is necessary to address the components required for moral and character maturation, and develop them through the implementation of programs specialized in this domain such as TPSR or Sports Education. The application of these supportive practices is a task to be performed and conducted by professionals of physical activity and education such as teachers, coaches, and other educators, inside and outside the schools, with the intention of generating transference of values and attitudes acquired through sports to the rest of other areas of life. This contribution to a more respectful and tolerant society is a responsibility that teachers and coaches should embrace and approach with professionalism.

Nevertheless, researchers found limitations through the development of the study related to duration of the implementation period and the time frame available for the application of the TPSR program. Another limitation found was related to size of the sample, reduced from the initial expectations, due to the impediment of involving a larger number of participants in consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Future lines of research should consider a longer intervention period, and the possibility of applying the TPSR program in different samples and contexts other than schools, such as camps or extra-curricular activities. It would result of great interest and importance to explore and study the transference and maintenance of the outcomes obtained from this program in other facets of life outside the school. Finally, it would be interesting to continue investigating the effectiveness and applicability of programs of this type in different age groups with the intention of building a consistent set of supportive practices available for professionals and students.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Bandura A (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

|

|

|

|

Beller JM, Stoll SK (1993). Sportsmanship: An antiquated concept? Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance 64(6):74-79.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Berkowitz MW, Hoppe MA (2009). Character education and gifted children. High Ability Studies 20(2):131-142.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Burgueño R, Medina-Casaubón J (2020). Sport Education and Sportsmanship Orientations: An Intervention in High School Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17(3):837.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Burgueño R, Cueto-Martín B, Morales-Ortiz E, Medina-Casaubón J (2020). Influence of Sport Education on high school students' motivational response: a gender perspective. RETOS-Neuvas Tendencias en Educacion Fisica, Deportey Recreacion (37):546-555.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Brody S, Siegel M (1992). The evolution of character. Madison, Connecticut: International Universities Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Carbonell AE (2012). Applying the teaching personal and social responsibility model (TPSR) in Spanish schools context: Lesson learned. Ágora para la Educación Física y el Deporte 14(2):178-196.

|

|

|

|

|

Carlson TB, Hastie PA (1997). The student social system within sport education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 16(2):176-195.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Compagnone N (1995). Teaching responsibility to rural elementary youth: Going beyond the urban at-risk boundaries. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance 66(6):58-63.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

DeBusk M, Hellison D (1989). Implementing a physical education self- responsibility model for delinquency-prone youth. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 8:104-109.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Diedrich KC (2014). Using TPSR as a teaching strategy in health classes. Physical Educator 71(3):491.

|

|

|

|

|

Doty J (2006). Sports build character?!. Journal of college and character 7(3). https://doi.org/10.2202/1940-1639.1529.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dunn JG, Dunn JC (1999). Goal orientations, perceptions of aggression, andsportspersonship in elite male youth ice hockey players. The Sport Psychologist 13(2):183-200.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Escartí A, Gutiérrez M, Pascual C, Llopis R (2010). Implementation of the personal and social responsibility model to improve self-efficacy during physical education classes for primary school children. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy 10(3):387-402.

|

|

|

|

|

Esentürk OK, Ilhan EL, Celik OB (2015). Examination of high school students' sportsmanlike conducts in physical education lessons according to some variability. Science, Movement and Health 15(2):627-634.

|

|

|

|

|

Evangelio C, Sierra Díaz J, González Víllora S, Fernández Río FJ (2018). The sport education model in elementary and secondary education: A systematic review. Movimento, 24.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Filiz B (2017). Applying the TPSR Model in Middle School Physical Education: Editor: Ferman Konukman. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance 88(4):50-52.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Goldstein JD, Iso-Ahola SE (2006). Promoting Sportsmanship in Youth Sports:Perspectives from Sport Psychology. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance 77(7):18-24.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Giebink MP, McKenzie TL (1985). Teaching sportsmanship in physical education and recreation: An analysis of interventions and generalization effects. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 4(3):167-177.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gordon B, Thevenard L, Hodis FA (2012). A national survey of New Zealand secondary schools Physical Education programs implementation of the teaching personal and social responsibility (TPSR) model. Agora para la Educación Física y el Deporte 14(2):197-212.

|

|

|

|

|

Hastie P (1998). Applied benefits of the sport education model. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance 69(4):24-26.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hellison DR (2011). Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility Through Physical Activity. United States: Human Kinetics.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Keating JW (1964). Sportsmanship as a moral category. Ethics 75(1):25-35.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Koc Y (2017). Relationships between the Physical Education Course Sportsmanship Behaviors with Tendency to Violence and Empathetic Ability. Journal of Education and Learning 6(3):169-180.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Koç Y, Yeniçeri S (2017). An investigation of the relationship between sportsmanship behavior of students in physical education course and their respect level. Journal of Education and Training Studies 5(8):114-122.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Manzano-Sánchez D, Valero-Valenzuela A, Conde-Sánchez A, Chen MY (2019). Applying the personal and social responsibility model-based program: Differences according to gender between basic psychological needs, motivation, life satisfaction and intention to be physically active. International Journal of Environmental Research And Public Health 16(13):2326.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Merino-Barrero JA, Valero-Valenzuela A, Pedreño NB, Fernandez-Río J (2019). Impact of a sustained TPSR program on students' responsibility, motivation, sportsmanship, and intention to be physically active. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 39(2):247-255.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mouratidou K, Goutza S, Chatzopoulos D (2007). Physical education and moral development: An intervention programme to promote moral reasoning through physical education in high school students. European Physical Education Review 13(1):41-56.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Pan YH, Huang CH, Lee I, Hsu WT (2019). Comparison of learning effects of merging TPSR respectively with sport education and traditional teaching model in high school physical education classes. Sustainability 11(7):2057.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Quinn RA, Houts AC, Graesser AC (1994). Naturalistic conceptions of morality: A question?answering approach. Journal of Personality 62(2):239-262.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Schiefele U (1991). Interest, learning, and motivation. Educational psychologist 26(3- 4):299-323.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Schwamberger B, Curtner-Smith M (2017). Influence of a training programme on a preservice teacher's ability to promote moral and sporting behaviour in sport education. European Physical Education Review 23(4):428-443.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Schwamberger B, Curtner-Smith M (2019). Moral development and sporting behavior in sport education: A case study of a preservice teacher with a coaching orientation. European Physical Education Review 25(2):581-596.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Shields DL, Bredemeier BJ (1986). Morality and aggression: A response to Smith's critique. Sociology of Sport Journal 3:65-67.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Shields DLL, Bredemeier BJL (1995). Character development and physical activity.Human Kinetics Publishers.

|

|

|

|

|

Shields DL, LaVoi NM, Bredemeier BL, PowerFC (2007). Predictors of poor sportspersonship in youth sports: Personal attitudes and social influences. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 29(6):747-762.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Siedentop D, Hastie P, Van der Mars H (2019). Complete guide to sport education.Human Kinetics.

|

|

|

|

|

Tsai E, Fung L (2005). Sportspersonship in youth basketball and volleyball players. Athletic Insight 7(2):37-46.

|

|

|

|

|

Vallerand RJ, Brière NM, Blanchard C, Provencher P (1997). Development and validation of the multidimensional sportspersonship orientations scale. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Vallerand RJ, Deshaies P, Cuerrier JP, Brière NM (1996). Toward a multidimensional definition of sportsmanship. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 8(1):89-101.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Wright PM, Burton S (2008). Implementation and outcomes of a responsibility-based physical activity program integrated into an intact high school physical education class. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 27(2):138-154.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Wright PM, Li W, Ding S, Pickering M (2010). Integrating a personal and social responsibility program into a wellness course for urban high school students: Assessing implementation and educational outcomes. Sport, Education and Society 15(3):277-298.

Crossref

|

|