ABSTRACT

The true statistics of orphans and vulnerable children (OVC) in Nigeria is not well known. Therefore, a lack of empirical data on the economic conditions of OVC in Nigeria has hampered the development of effective intervention strategies to mitigate their economic needs. This study assessed the economic activities and capabilities of caregivers in enrolled vulnerable households in Akwa Ibom and Rivers States into a project being undertaken by Association for Reproductive and Family Health (ARFH) on OVC. A cross sectional survey was conducted in 8 Local Government Areas in Akwa Ibom and Rivers States. Information on demographic and socio-economic characteristics of caregivers or heads of the households were collected. Descriptive statistics, T-test and X2- test were used for data analyses. There were 13,631 respondents/caregivers from both Local Government Areas. The commonest economic activity was petty business. The respondents did not have any prior training on other income generating activities. A sizeable proportion of caregivers saw finance as a major constraint to their business climate. The majority of caregivers of OVC in these states did not earn a living wage. Therefore, they will require vocational, business and financial literacy training for effective household economic strengthening program as an intervention strategy of any project.

Key words: Association for reproductive and family health (ARFH), orphans and vulnerable children (OVC), intervention strategy, business and financial literacy training.

The burden of orphans and vulnerable children (OVC) in Nigeria is not well known as the available information is scanty and inadequate. A situational assessment and analysis of OVC in 2008 gave an estimate of about 17.5 million OVC in the country (Daily Trust (2011); NRSA, 2009). This suggested that for every 10 Nigerian children, one of them is likely to be an orphan, 1/3 of whom is a maternal orphan and two-thirds are either paternal orphans or both (Daily Trust, 2011; NRSA, 2009; Save the children, 2015). In fact, the HIV/AIDS pandemic in recent years have increased the number of OVC and the poor socio-economic climate in Nigeria has resulted in the growing population of vulnerable households. The attendant hardships on the caregivers in providing basic needs for the OVC cannot be over-emphasized. These caregivers must have been experiencing difficulties on a daily basis in securing access to social basic services like education, food, portable water, protection, good hygiene and good health for their children or wards. Indeed, studies have reported that caregivers are over-burdened and not economically capable of providing for their orphans and vulnerable children (UNICEF, 2008; Nsagha et al., 2012). The consequences of the inability of caregivers to provide for their OVC are enormous. Often such a child is exposed to abuse, exploitation and social exclusion. The Rapid Assessment Analysis Action Planning (RAAAP, 2004) showed that a vulnerable child is less likely to enroll in school, more likely to drop out of school, more likely to be at higher risk of being involved in risky sexual behavior, and participate in substance abuse. Also it is well known that a likely consequence of poverty is to influence the food security status of households which can lead to an increase in the likelihood of risky sexual behavior among female children, a risk factor of HIV/AIDS (UNICEF, 2008). However, lack of reliable empirical data on the socio-economic conditions of OVC in Nigeria has hampered the development of effective policies and programs to address their specific needs. While we know that poverty is associated with orphan state, the relationship to level of poverty is not so clear. A question which sometimes come to mind is ‘how poor is poor?’ Some studies reported disparities or inequalities exist in economic situations of households (Awoyemi and AbdulKarim, 2009; CDC, 2011; Kochhar and Fry, 2014; Fagbamigbe et al., 2015). There is the increasing realization that poverty itself is dynamic “that some of the poor are not poor all of the time” meaning that an historical harmony has been established between poverty and vulnerability (Yaqub, 2000). So there is the need to know the economic climate of vulnerable households in Nigeria to provide a road map for developing appropriate intervention strategies for mitigating poverty of OVC caregivers. Previous studies have shown that household economic situation is positively and significantly associated with access to health care services and other basic needs of children (Oritz, 2007; Celik and Hotchkis, 2000). Hence, any effective strategy, expected to mitigate the impact of the burden of poverty on orphans and vulnerable children requires a household economic assessment (HEA). HEA has been defined as a framework for analyzing how people obtain food, non-food goods and services (such as access to education and health of children) and how they might respond to changes in their external environment like a drought or a rise in food prices (Holzman et al., 2008).

Thus, a Household Economic Assessment will inform the portfolio of interventions that will reduce the economic vulnerability of the OVC families and empower them to provide for the essential needs of the children they care for, rather than relying on external assistance (Economic Strengthening (2016). Besides, a good knowledge of the baseline economic situation of the vulnerable households will guide the prioritization of type of support for the caregivers of these OVC households and a platform for the future evaluation of any intervention.

Therefore, the objective of the present study is to assess the socio economic activities and capabilities of caregivers in OVC households enrolled in a LOPIN project by the Association for Reproductive and Family Health (ARFH). The study will determine their sources of household income and expenditures, household assets, coping mechanisms during periods of emergency, and potential income generating activities that can increase household livelihoods. The saying that ‘If what happened yesterday is reflected in today’s status and what happened today influences tomorrow’s status’, then the findings of the present study will inform positively the Household Economic Strengthening intervention strategy of the Association of Reproductive and Family Health (ARFH) LOPIN REGION 1 project for orphans and vulnerable children, including the kind of income generating activities that would be most beneficial for vulnerable households in Rivers and Akwa Ibom states of Nigeria to undertake.

This is a descriptive cross sectional survey conducted in 5 Local Government Areas (LGAs) in Akwa Ibom state and 3 others in Rivers state. The LGAs in Akwa Ibom states are: Ikot Ekpene, Okobo, Oron, Uruan and Uyo while those in Rivers State are: Port Harcourt, Eleme, and Obio/Akpor. The LGAs were purposely selected because they constitute the PEPFAR/USAID priority LGAs with high prevalence of HIV and OVC burden (PEPFAR, 2012). There were 5,254 and 8,377 vulnerable households already selected for intervention in Rivers State and Akwa Ibom State, respectively. The National Vulnerable Assessment Questionnaire was used to identify the vulnerable households (Federal Ministry of Women Affairs and Social Development, Nigeria, 2009; Bamgboye et al., 2017). The household economic assessment, was carried out between May and July 2016 by the Association of Reproductive and Family Health (ARFH), a local non-governmental organization located in Ibadan, South West Nigeria.

Data collection

A structured- questionnaire adapted from MEASURE Evaluation OVC tool kit was used to obtain information by personal interview on the demographic characteristics of the caregivers of the identified vulnerable households, their household socio economic characteristics, including household income, saving and loans practice as well as being able to access and obtain membership of a savings groups (MEASURE Evaluation, 2014). There was also an enquiry about their income generating activities and interests of the OVC caregivers. These caregivers were also asked about the constraints or obstacles to doing business as well as their general perceptions of their economic situations. Ethical consideration was through an informed consent obtained from each respondent.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics such as means, medians and standard deviations were used to summarize quantitative variables while categorical variables were summarized with proportions and percentages. The wealth index was calculated using standard methods as described in previous publications (Fagbamigbe et al., 2015). The Student-T-test and X2- test were used to determine significant differences between two mean values and associations between any two categorical variables respectively. The results were presented in appropriate tables and graphs. The statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS version 21 (IBM SPSS, 2007).

Demographic characteristics of caregivers of OVC in Akwa Ibom and Rivers states

There were 13,631 households in the two states consisting of 8,377 from Akwa-Ibom state and 5,254 from Rivers state. The mean age of the caregivers in the two states was 38.7 years (SD=11.4), statistically significantly higher in Akwa-Ibom State, 39.7 years (SD=12.0) than Rivers-state 37.0 years (SD=10.2; t=395.059, p<0.001). The males in Akwa-Ibom state with mean age of 42.2 years (SD-12.5) were older than their female counterpart (mean=40.5 years; SD=9.9; t=303.112, p<0.001). Similarly, the mean age of males in Rivers State (41.2 years; SD=10.8) was significantly higher than their female counterpart (35.7 years; SD= 9.7) (t=261.982, p<0.001). The sex distribution of caregivers in Akwa-Ibom State showed a higher proportion of women (55.1%) given a sex ratio of 0.81 while the caregivers from Rivers had a sex ratio of 0.29 as women constituted 77.2%. Less than 5% of the caregivers were 65 years old and above being 4.12% in Akwa-Ibom State and 2.0% in Rivers state.

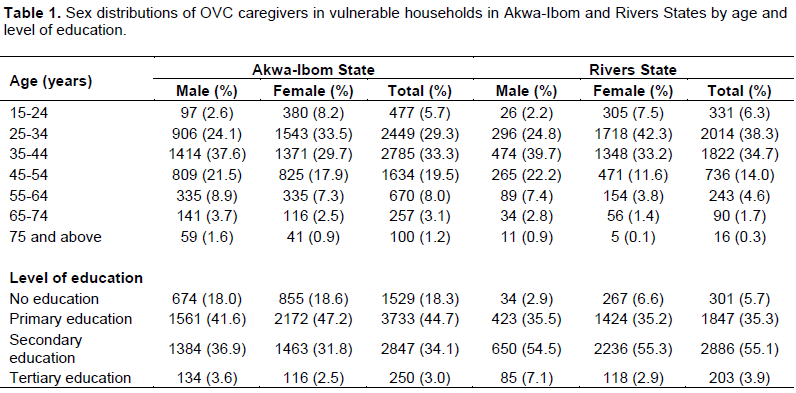

The results presented in Table 1 showed about one-fifth (18.3%) of the caregivers in Akwa- Ibom State had no formal education with a similar proportion in males (18.0%) and females (18.6%). Almost half of the respondents had primary education in Akwa-Ibom state with a lower proportion in males (41.6%) than females (47.2%). A small proportion of caregivers (3.0%) from Akwa Ibom state had tertiary education. The association between education and gender was statistically significant, X2=35.963, P<0.001. The situation was slightly different in Rivers state where only about 6% had no formal education and about half (55.1%) had secondary education with similar proportions in males (54.5%) and females (55.3%). About 4% had tertiary education, slightly higher than what was observed in Akwa Ibom State. Also, gender was statistically significantly associated with education (X2= 24.403, P<0.001).

Socio economic conditions of the OVC in Akwa-Ibom and Rivers States

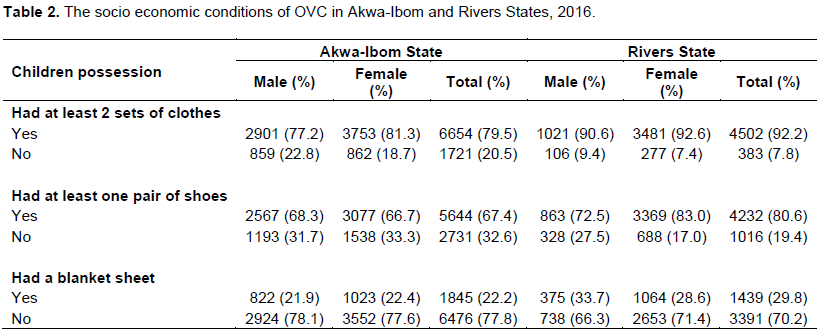

Table 2 showed that 80% of the children in Akwa-Ibom state had at least two sets of clothes slightly lower in males (77.2%) than females (81.3%). And about two-thirds (67.4%) of them had at least one pair of shoes, with no difference between the sexes [males (68.3%) and females (66.7%|)]. Less than a-quarter of the children (22.2%) had a blanket or covering sheet with similar proportions in males (21.9%) and females (22.4%).

In Rivers State, almost all the children (92.2%) had at least two sets of clothes (males: 90.6%; females: 92.6%). About 73% of them possessed at least one pair of shoes with lower proportions among males (males: 72.5%; females: 83.0%) and about 30% of them had a blanket or covering sheet (males: 33.7%: females: 28.6%).

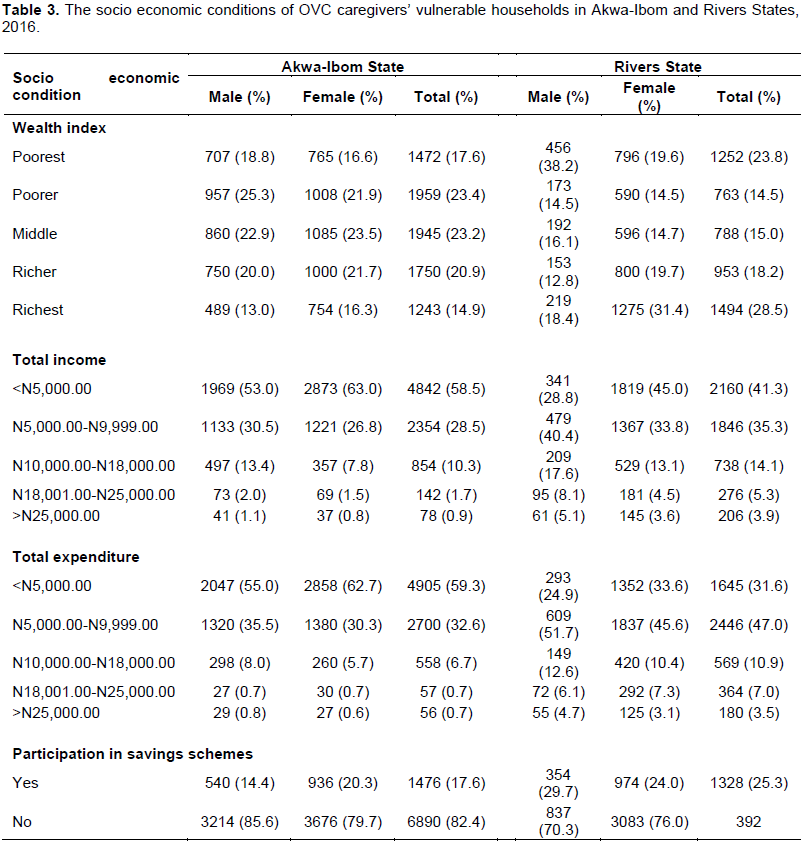

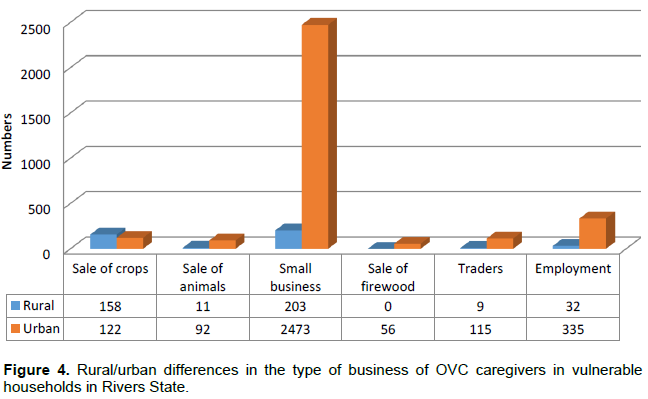

In Akwa-Ibom State, Table 3 showed that more than one-fifth (23.4%) of the caregivers were in the poorer wealth category and a similar proportion (23.5%) in the middle wealth category; also similar in males (22.9%) and females (23.5%). The lowest proportion of the respondents (14.9%) was in the richest category lower in males (13.0%) than females (16.3%). Also, in Rivers State, the lowest proportion of the respondents (14.5%) was in the poorer category while 29% was in the richest category with much lower proportion among males (18.4%) than females (31.4%).

In Akwa-Ibom State, nearly 60.0% of the respondents earned less than ₦5000 monthly, slightly higher in males (63.0%) than females (53.0%). Also, about 31% of the respondents earned ₦5000-₦9999 lower in males (26.8%) than females (28.5%). However, a few people (1.1%) earned above ₦25000 (0.8% males and 1.1% females). In Rivers state, 41% of the respondents earned less than ₦5000 (28.8% of males and 45.0% of females). Also, just a little above one-third of the respondents (35.3%) earned between ₦5000 to 9999 (40.4% males; 33.8% females). And less than 5% earned above ₦25000 (3.6% males; 3.9% females).

The spending pattern of Caregivers in Akwa-Ibom state showed about 60% (59.3%) spent less than ₦5000 a month (males: 55.0%; females: 62.7%). Another one-third spent between ₦5000 and ₦9999 (35.5% males; 30.3% females), and very few (0.7%) spent above ₦18001. In Rivers State, almost one-third of the respondents (31.6%) spent less than ₦5000 (24.9% males; 33.6% females), again, the highest proportion of the respondents (47%) spent between ₦5000-₦9999 (males: 51.7% males and 45.6% females). The proportion of respondents that spent above N25,000 was only 3.5% (4.7% males and 3.1% females). Less than one-fifth of the respondents (17.6%) participated in savings (14.4% males; 20.3% females) in Akwa-Ibom state, the proportion was higher in Rivers state with approximately one-quarter of the respondents (25.3%) having participated in savings scheme (29.7% males and 24.0% females).

Sex differentials in business climate of OVC caregivers in Akwa-Ibom and Rivers States

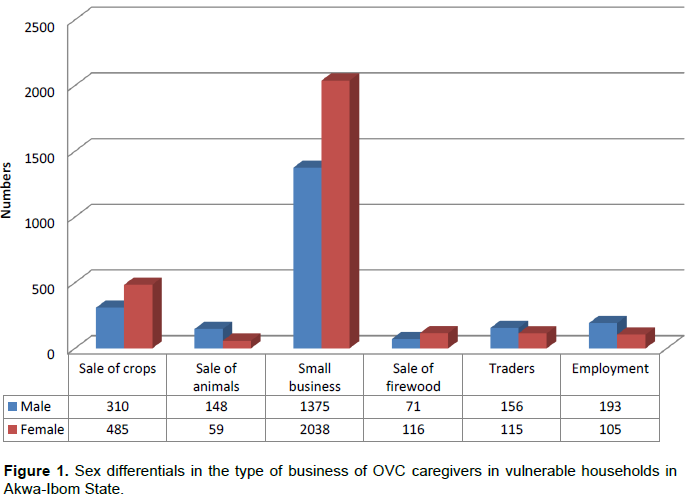

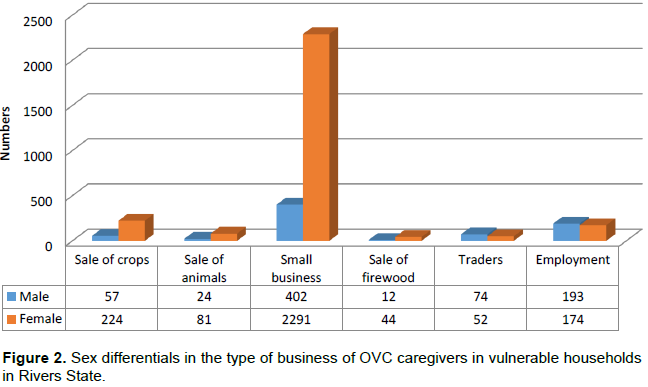

Figure 1 showed that in Akwa-Ibom State, about two-thirds of the caregivers (66.0%) engaged in small business and the proportion was higher among female respondents (69.8%) than their male (61.0%) counterparts. Only a few caregivers (5.8%) were in paid employment higher among males (8.6%) than females (3.6%). Also, about three-quarters of the respondents in Rivers State (74.2%) were engaged in small business (52.8% males and 79.9% females). The results illustrated in Figure 2 indicated that about one-tenth of the respondents (10.1%) were in paid employment, higher among males (23.5%) than females (6.1%).

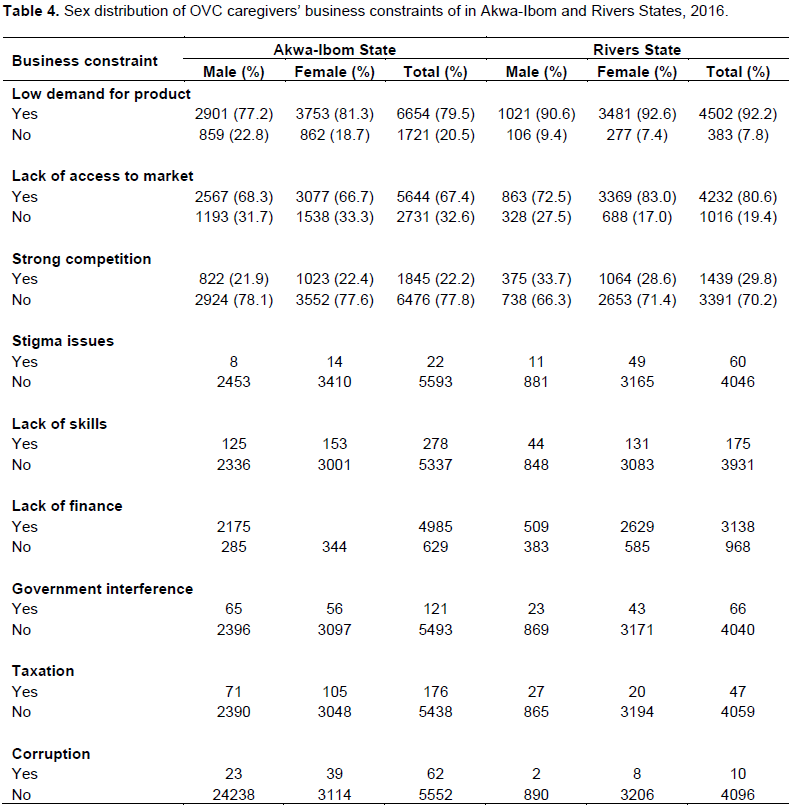

Constraints for doing business by sex

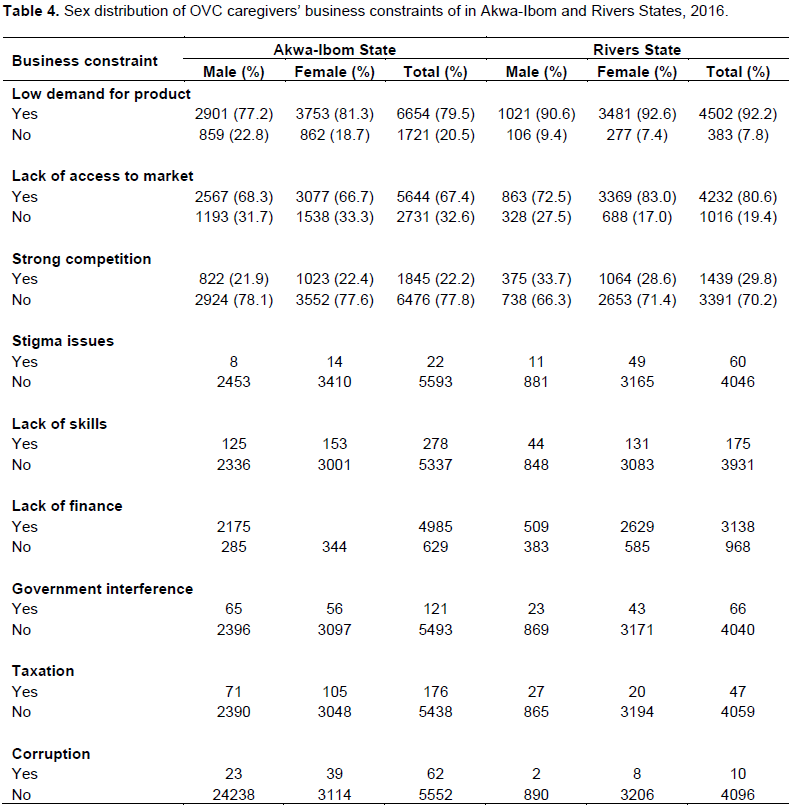

In Akwa-Ibom State, a low demand for their products is one of the major constraints for doing business reported by 18.1% of respondents with similar proportions in both sexes. And about 11.0% reported that poor market outlet constrained them from doing business similar in both sexes (10.5% males, 11.3% females). However, the major constraint to doing business expressed by a very sizeable proportion of the respondents (88.8%) irrespective of sex was finance [female (89.1%) and male (88.4%)]. Less than 5% attributed heavy taxation, HIV stigma, and poor skill as constraints to embarking on business in Akwa Ibom State.

The situation was similar in Rivers state where 13.9% of the caregivers indicated low demand for products as constraint to business similar in males (15.5%) and females (13.4%). Less than 5% mentioned poor access to market (3.0%) as constraints to business lower to what was reported in Akwa-Ibom state. These results presented in Table 4 also revealed that the major constraint to doing business was lack of finance mentioned by more than three-quarters of the respondents (76.4%) and this was higher in females (81.8%) than males (57.1%). Less than 5% mentioned stigma issues, taxation, and poor skill as other constraints to business in this state. There were no sex differentials in these constraints.

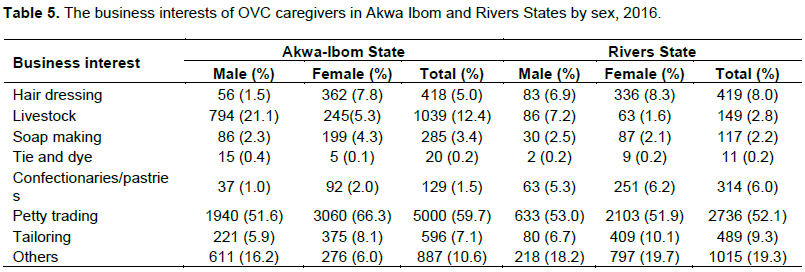

Table 5 showed almost 60% of the respondents from Akwa-Ibom state would like to embark on petty trading if given an opportunity to make a choice and this was lower in males (51.6%) than females (66.3%). However, a fifth of the males in Akwa Ibom would love to engage in livestock compared with only 5% of the females if there is opportunity in future.

In Rivers State, 52.1% (males: 53%; females: 51.9%) of the respondents would like to be petty traders in the future. However, about 10% of the caregivers would love to learn tailoring and this was similar in both sexes.

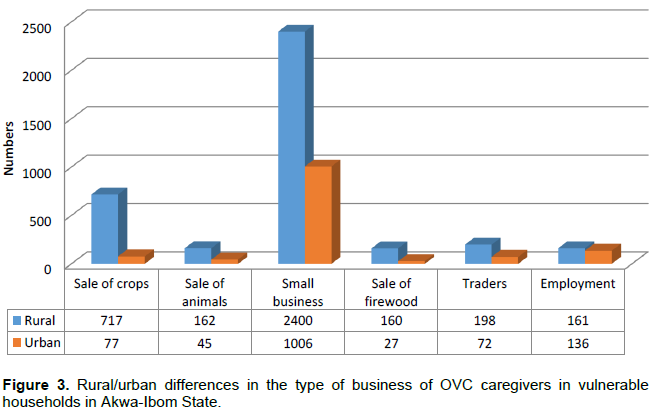

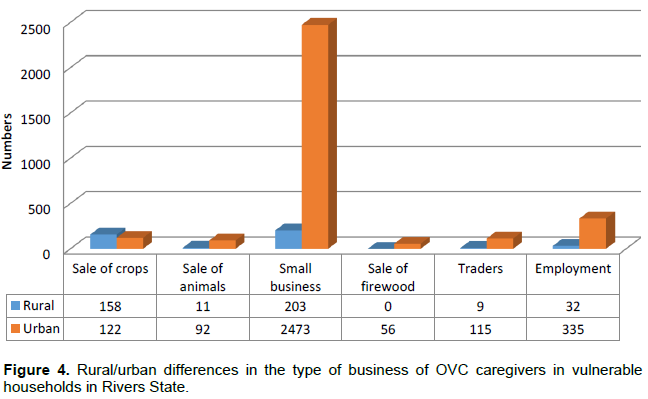

Rural/urban differences in business climate of OVC caregivers in Akwa-Ibom and Rivers States

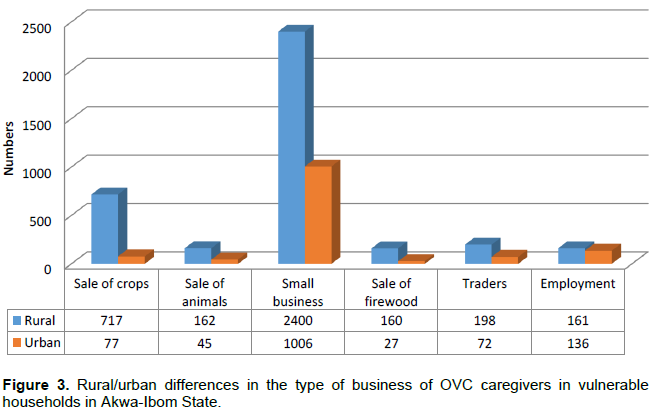

The study showed that slightly less than two-thirds of the respondents (63.2%) living in the rural areas of Akwa-Ibom State, engaged in small business compared to almost three-quarters of the respondents (73.8%) living in the urban areas. A higher proportion of respondents in rural areas (19%) engaged in the sale of crops compared to only 6% of respondents residing in the urban areas. However a higher proportion of urban dwellers were in paid employment (10%) compared to those in rural (4.2%) areas as presented in Figure 3.

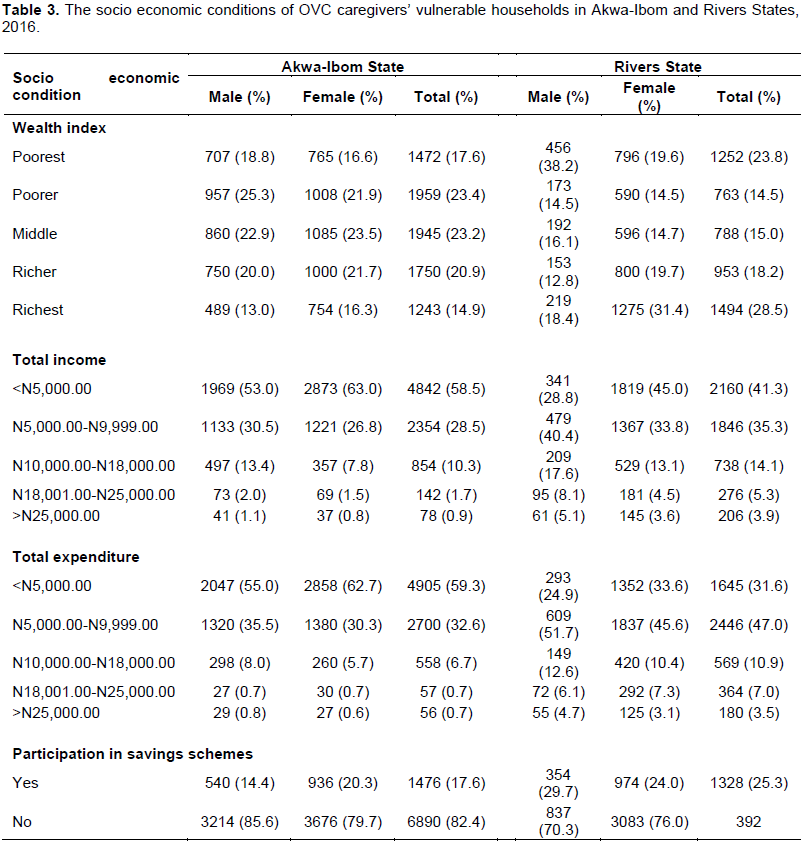

Figure 4 shows the rural urban differentials in the type of business undertaken by the caregivers or respondents in Rivers State. About half of respondents living in the rural areas (49.2%) engaged in small business compared to more than three-quarters of those living in urban areas (77.5%). Almost 40% of rural dwellers engaged in the sales of crops compared to about 4% of respondents residing in the urban areas. But, a slightly higher proportion of the respondents living in the urban areas (10.5%) were in paid employment compared to their rural counterparts (7.7%).

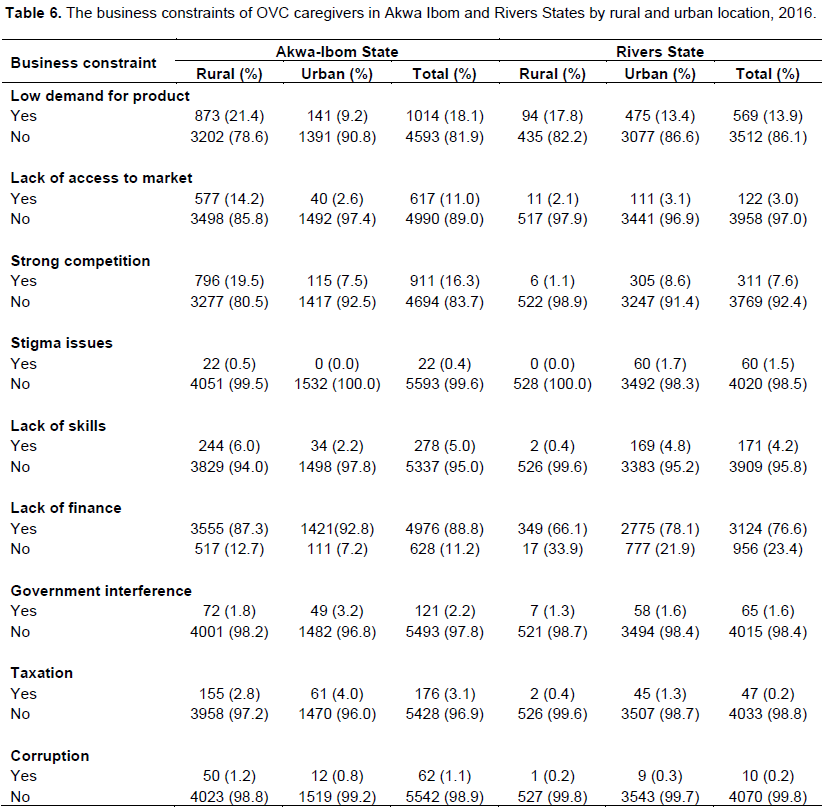

Constraints for doing business by location

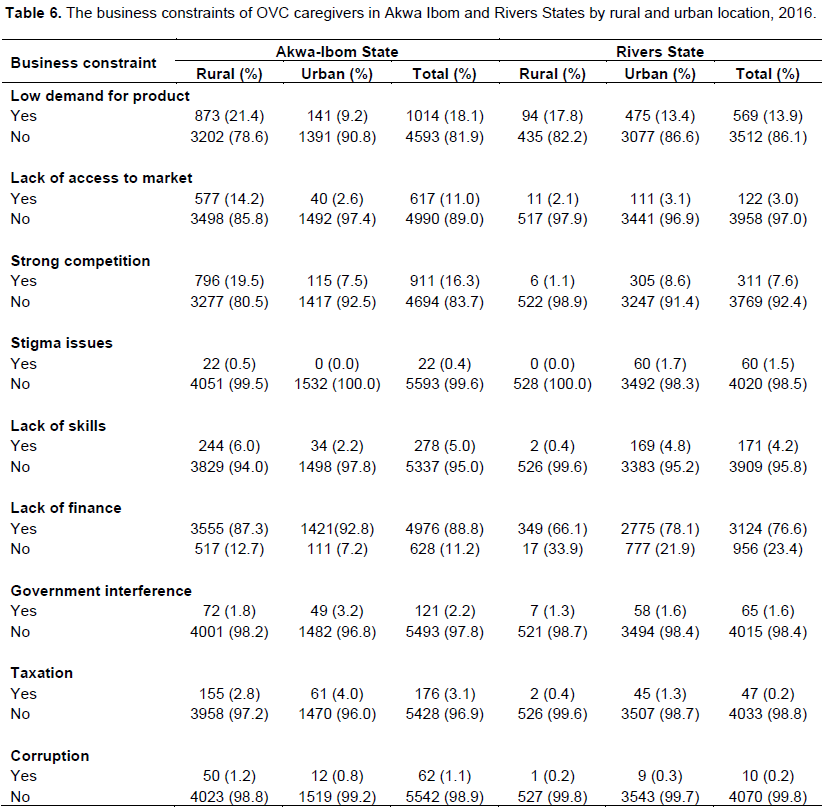

The data on business constraints of caregivers presented in Table 6 showed that about a fifth of caregivers in the rural areas (21.4%) of Akwa-Ibom State, indicated low demand for their products as a constraint compared with less than 10% (9.2%) among those living in urban respondents. A very small proportion of the urban respondents (2.6%) were constrained to doing business due to lack of access to market compared to their rural counterparts (14.2%). About 87% of the rural respondents reported financial constraints to doing business while this was reported by higher proportion among urban dwellers (92.8%). A small proportion mentioned taxation as constraints among both rural (2.8%) and urban respondents (4.0%).

In this study, the major constraint of most caregivers to doing business in Rivers State was finance as reported by about two-thirds of the respondents (66.1%) living in the rural areas and more than three-quarters of respondents (78.1%) in the urban areas. The least mentioned constraint was taxation indicated by only 0.4 and 1.3% of rural and urban dwellers respectively. Also, about 18% of respondents living in rural areas expressed that their major constraint to successful business was low demand for their products compared with 14% of urban respondents. A few residents in both urban (3.1%) and rural (2.1%) areas indicated lack of access to market as constraints to successful business.

Preferred business

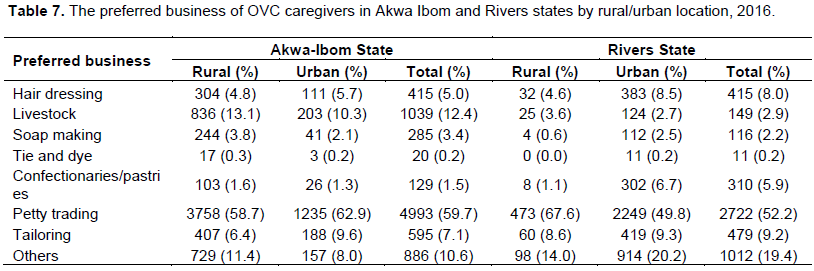

The data presented in Table 7 showed that in Akwa-Ibom State, almost 60% of the respondents residing in the rural areas would want to be petty traders, a business mentioned by a slightly higher proportion of urban residents (62.9%). Livestock business was preferred by 12% of respondents from Akwa Ibom state and this was slightly higher among rural dwellers (13%). About 5% of respondents would want to be hairdressers, similar in both rural and urban areas. Unfortunately, the other business indicated by a seemingly sizeable number of respondents (11.4%) living in the rural areas and 8.0% of the respondents living in the urban areas were not specified.

Also,in Rivers state, more than two-thirds of the living in the rural areas and 20.2% of those in the urban areas did not specify any kind of business.

The findings in this study showed that the average age of caregivers or household heads which was higher in Akwa Ibom than their counterparts from Rivers State is similar to the report of the 2013 NDHS which showed slight regional variations across states in South- South region with respect to age of household heads (NDHS, 2013). A plausible explanation could be the movement of youths to the coastal areas occupied by Rivers State leaving their families with their parents who are older in the hinterland.

Another important finding in this study is the differential sex ratio between Akwa Ibom and Rivers State which showed more female caregivers or head of households in Rivers State than in Akwa Ibom. The plausible explanation for this could be the constant migration of younger ones from the hinterland to the coastal area where there is a better economy and increasing urbanization. The females in the rural areas are more exposed to unprotected casual sex and in most cases the men who impregnated these girls or married them either absconded or died from the risky behaviors they engage in the quest to making money because of the increasing rise in the prices of goods and services that characterize urban cities they ran to. This leads to many families being headed by females in the rural areas and the higher ages of males than females as the young males have migrated to urban areas for greener pastures.

The fact that a high proportion of caregivers or household heads with formal education was higher in Rivers State than Akwa Ibom also corroborates the recent NDHS finding which shows that the proportion of women who completed secondary education in Rivers State was higher than in Akwa-Ibom and indeed any other states within the South-South region (NDHS, 2013). This is not to be surprising if we one recognizes that Port Harcourt, capital of Rivers State was one of the coastal cities that had early contact with the missionary people, a phenomenon associated with early exposure to western education and rapid urbanization (NDHS, 2013). Also, since majority of the caregivers in Rivers State were females, their access to formal education in Rivers State also explains the high disparity with caregivers from Akwa Ibom State. Again the literacy level of the two states which was better in Rivers State than in Akwa-Ibom State is in line with findings of a study which revealed that poverty and vulnerability to poverty are highest among household headed by persons with low education (Md. Shafiul and Katsushi, 2009).

The present economic situation of vulnerable households in Akwa-Ibom and Rivers States showed that the poverty level in the two states was high, but higher in Akwa Ibom than Rivers State. The total income from all members of households in Akwa Ibom state was poorer than those from Rivers State. It is not surprising that a higher proportion of respondents from Rivers State were in the richest category of wealth index scale while the reverse was observed in Akwa Ibom State whereby the highest proportion of the respondents was in the poor category of the wealth index scale. Another finding that showed a higher proportion of children in Rivers State having access to basic social needs like clothing or blanket compared with their counterparts in Akwa Ibom State corroborates an earlier study that reported higher prevalence of income poverty in Akwa-Ibom State than neighboring states (Umoh et al., 2015). The use of children possession of basic materials as an indicator of poverty level in this study is in line with the World Bank definition of poverty as any person who is deprived in any one of the dimensions: Material measured by income or consumption, low achievements in education and health, vulnerability and exposure to risk, noiselessness and powerlessness (World Bank, 2001). However, a UNICEF study defined absolute poverty as “a condition characterized by severe deprivation of basic human needs (UNICEF, 1998).

Again since Education is found to be a key element to reducing poverty, the relatively higher level of poverty in Akwa Ibom State than that observed in Rivers State can partly be explained by the higher educational level of caregivers observed in Rivers State (Ballara, 2002). The observed higher earning capacity in Rivers State than that found in Akwa Ibom State can also be attributed to the rapid industrialization of Rivers State as a result if its location at the coastal areas where the oil business thrives. This factor can also explain the higher proportion of people in paid employment in Rivers than Akwa Ibom State.

The choice of petty trading as the major business of interest in Akwa Ibom and Rivers State could be attributed to the limited knowledge of other trades than buying and selling. Again, there is the issue of ignorance that petty trading can only earn them what to eat and not for living well. This finding is similar to previous work in Nigeria that reported low household agricultural productivity and associated low income to have resulted in persistent food insecurity particularly in the rural and low income urban households (Abimbola and Kayode, 2013). The environment can also explain why a higher proportion of urban dwellers do business and the sale of crops and livestock was relatively commoner among rural dwellers. Another explanation can be that more arable land for farming may be available in the rural areas than the urban.

The finding that lack of finance is the common denominator of the constraints to carrying out profitable income generating activities is worthy of note. Every business requires adequate financing and not surprising that these vulnerable households attributed their poor economic condition to lack of finance. It is therefore suggested that the provision of financial support to the caregivers may increase their resilience to provide for their families. One other finding that showed a higher proportion of rural respondents had financial constraint than those in urban areas could be due to the exposure to a high economy of urban dwellers in the states. The lower demand of products that was found higher in rural areas could be as result of the market whereby many caregivers produce the same things within a small population contrary to the ever increasing population in the urban areas.

A sizeable proportion of respondents in this study earned below the minimum wage of 18,000 naira in Nigeria and did not have or receive any education on any income generating activities. A small proportion was aware of the need to save money but could not save because most of them did not even earn enough to meet their basic household needs. Very low proportion had received any type of educational assistance or training on types of good business and its management.

There is need to improve access to education in the rural communities which is likely to increase their awareness about business that could be lucrative. Also giving them appropriate orientation would also help them to know how to source for the capital to start up any business of choice. It is recommended that the governments in the two states should facilitate the type and quality of education in their states to include courses in entrepreneurships and small scale empowerment programs.

The household economic strengthening program of the Association for Reproductive and Family Planning (ARFH) should support the vulnerable households in the choice of business that will reduce their poverty level but should be accompanied by appropriate training in entrepreneurship and skill acquisition.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Abimbola OA, Kayode AA (2013). Food insecurity status of rural households during the post- planting season in Nigeria. J. Agric. Sustain. 4(1):16-35.

|

|

|

|

Awoyemi TT, Abdulkarim A (2009). Explaining Polarization and its Dimensions in Nigeria: A DER Decomposition Approach. Paper prepared for the 14th Annual Conference on Economic Modeling for Africa, Abuja, Nigeria 8-10 July 2009. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Ballara M (2002). Women and Literacy: Women and Development Series. London, Zed Books Limited.

|

|

|

|

|

Bamgboye EA, Odusote T, Olusanmi I, Nwosu J, Phillips–Ononye T, Akpa OM, Yusuf OB, Adebowale AS, Todowede O, Ladipo OA (2017). School absenteeism among Orphans and Vulnerable Children in Lagos State, Nigeria: a situational Analysis. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. An International Inter-discipl. J. Res. Policy Care. DOI:10.1080/17450128.2017.1325545.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

CDC (2011). Health Disparities and Inequalities Report- United States 2011. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Celik Y, Hotchkiss DR (2000). The socio-economic determinants of maternal health care utilization in Turkey. Soc. Sci. Med. 5:1797-806.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Daily Trust (2011). Nigeria: Women Ministry Launches Database for Orphans. Minister of Women Affairs and Social Development "Hajiya ZM" National Situation Assessment and Analysis (NSAA) of the Nigerian populace in 2008 estimated that there were about 17.5 million Orphans and Vulnerable children (OVC) in the country. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Economic Strengthening (2016). PEPFAR working definition, 2011. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Fagbamigbe FA, Bamgboye EA, Yusuf OB, Akinyemi JO, Issa BK, Ngige E, Amida P, Bashorun A, Abatta E (2015). The Nigeria wealth distribution and health seeking behavior: evidence from the 2012 national HIV/AIDS and reproductive health survey. Health Econ. Rev. 5(1):5.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Federal Ministry of Women Affairs and Social Development (2009). Nigeria research situation analysis on orphans and other vulnerable children. Boston University Center for Global Health and Development,. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Holzman P, Boudreau T, Holt J, Lawrence M, O' Donnell M (2008). The Household Economic Approach, A Guide for Programme Planner and Policy-makers, Save the Children, UK. Available at:

View.

|

|

|

|

|

IBM SPSS Inc (2007). SPSS for Windows, Version 16.0. Chicago, SPSS Inc.

|

|

|

|

|

Kochhar R, Fry R (2014). Wealth inequality has widened along racial, ethnic lines since end of great recession. Pew Res. Center 12:1-15.

|

|

|

|

|

Md. Shafiul A, Katsushi SI (2009). Vulnerability and poverty in Bangladesh, ASARC Working Paper 2009/02.

|

|

|

|

|

Measure Evaluation (2014). Collecting PEPFAR Essential Survey Indicators: A supplement to the Orphans and Vulnerable Children Survey Tools - Guide. MS-14-90. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) (2013). National Population Commission Federal Republic of Nigeria Abuja, Nigeria.

|

|

|

|

|

Nigeria Research Situation Analysis (NRSA) (2009). Orphans and Other Vulnerable Children Final Report. Available at:

View.

|

|

|

|

|

Nsagha DS, Bissek AC, Nsagha SM, Assob JC, Kamga HL, Njamnshi DM, Njamnshi AK (2012). The Burden of Orphans and Vulnerable Children Due to HIV/AIDS in Cameroon. Open AIDS J. 6:245-258.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Oritz AV (2007). Determinants of demand for antenatal care in Colombia. Health Policy (New York). Health Policy 86(2-3):363-72.

|

|

|

|

|

PEPFAR (2012). The United State President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) Guidance for Orphans and Vulnerable Children Programming. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Rapid Assessment Analysis and Action Planning Process (RAAAP) for Orphaned and Vulnerable Children (2004). Indiana University. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Save the children (2015). State Of Nigerian Children 2015: Children Left Behind in Nigeria World Bank 2011. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Umoh NE, Offiong RA, Ekpe IA, Yta EM, Enya EA (2015). Assessment of income poverty among farmers in Akwa Ibom state, Nigeria. JETEMS 6(8):345-349.

|

|

|

|

|

UNICEF (1998). The State of the World Children. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

UNICEF (2008). A Situation Analysis of Orphans and Vulnerable Children in Rwanda. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

World Bank (2001). The World Bank annual report 2001: Year in review (English). World Bank strategy for meeting the poverty challenge. Available at:

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Yaqub S (2000). Inter-temporal Welfare Dynamics: Extents and Causes" Conference Paper given at Brookings Institution/Carnegie Endowment Workshop, Globalization: New Opportunities, New Vulnerabilities.

|

|