ABSTRACT

The aim of this paper is to verify if there is a typical enterprise model for the development of immigrant female entrepreneurship in Italy. Based on the literature on the subject, however, it is useful to ask the following research question: “can membership in a national and international network facilitate the development of immigrant female entrepreneurship operating in Italy”? The survey was carried out by submitting a questionnaire to a sample of immigrant women entrepreneurs in the textile and clothing sector based in Italy. The choice fell on this specific economic segment because it represents the third largest sector for the number of female immigrant entrepreneurs (2.271 units) which amounts to 16% of the total number of entrepreneurs operating in the same sector. The percentage of respondents was 35%, with 795 completed questionnaires. The structure of the questionnaire reflects the need to examine the personal features of female entrepreneurs, the organizational aspects and the style of leadership, the task environment in which the enterprise works and the main possible benefits, or obstacles, they might obtain, or face. In addition to the objective of enlarging the literature regarding the management and governance of businesses run by women entrepreneurs, that is quite limited to date, this paper is a contribution to the analysis of a possible development model of women entrepreneurs.

Key words: Entrepreneurship, network, resilience, women entrepreneurs, competitive advantage.

As part of the national and international debate, immigrant entrepreneurship has been analyzed from many different points of view, emphasizing personal, psychological and socio-cultural aspects of immigrant entrepreneurs and the social context in which they operate (Light and Bhachu 2004; Clydesale 2008; Lin and Tao 2012).

The immigrant entrepreneurship incentives are linked to factors such as desire for self-fulfillment, risk appetite, identification of market opportunities and personal dissatisfaction related to social issues (Aviram, 2009). Compared with resident population, immigrants have limited skills and human capital resources, necessary to create and access networks, because of their difficulty to acquire information and evaluate market opportunities (Flap et al., 2000; Alder and Kwon 2002; Kloosterman 2010).

Likewise, immigrants have insufficient language skills and are bound to encounter numerous obstacles to access to the credit market. The transition from being employed to self-employed can represent a reward and an enhancement of their own entrepreneurial ambition (Rajiman and Tienda, 2000).

It is clear that the economic and social disadvantage in which immigrants live is just one of the many negative conditions that stimulate their need for change (De Clercq and Honig, 2011; Vinogradov and Gabelko, 2010; Labrianidis and Hatziprokopiou, 2010; Valenzuela, 2001).

At the same time, the lack of adequate education, the limited access to financial resources and poor language skills can also influence the choice of the economic sector where to start a business. Usually, the immigrant entrepreneur is more oriented towards markets that the local entrepreneur tends to neglect. These are markets that you can access through a limited allocation of capital, where the technological barriers are low and where the enterprise sizes are relatively modest and where, due to the number of active companies, the potential for expansion and profit margins are lower than the market average (Rath and Kloosterman, 2000).

In such a complex environment, belonging to ethnic networks could make up for the lack of full integration of immigrants in the economic fabric of the host country. This may stimulate the development of new businesses operating in new markets, and it may be a way to connect with new customers of different ethnicities, and to enable long lasting relationships with local institutions (Saxena, 2005; Valeri and Baiocco, 2012).

Taking all the aforementioned into account, this study examines whether there exists a possible development model of female entrepreneurship in Italy, focusing specifically on immigrant women’s entrepreneurship.

In an increasingly competitive environment, businesses need to have an appropriate level of knowledge and resources to cope with fierce competition. This need has led to the phenomenon of the specialization of businesses, reducing the number and type of knowledge and common assets. The collaborative process may be disturbed by factors as the high cognitive distance between individual companies and the simultaneous lack of resources to acquire new knowledge. In this sense, the network represents the best organizational model to promote the growth of small and medium-sized enterprises.

The ability of a network to innovate and compete successfully depends not only on the skill of the individual companies but also on the ability to govern the network of relationships between them. As widely claimed by management literature, the ability to oversee the dynamics of internal and external relations of the network is a way businesses can successfully compete with others in a hyper-competitive economy. Within the international scientific debate, many studies have focused on the analysis of the evolutionary dynamics of the network and on factors that influence their success over time (Gulati, 1998; Gulati and Gargiulo, 1999; Soda et al., 2004; Yin et al., 2012; Das and Teng, 2002).

Thanks to the interdisciplinary debate on network theory (Parkhe et al., 2006) we can mention a number of important contributions that identify the evolutionary phases of the creation and development of inter-organizational relationships, as for example:

1. The preconditions of exchange, or the reasons that led to the birth of the network.

2. The building conditions for any form of relations between enterprises

3. The operation of the network that presupposes the reaching of an agreement on the rules of future conduct and on the mechanisms to regulate conflict management.

The complexity and the increasingly competitive market pressure stimulate the formation and development of inter-organizational relationships, and they allow to acquire and exploit new resources and new knowledge, reducing the environmental uncertainty (Dickson and Weaver, 1997).

In particular, the network cooperation between small and medium-sized businesses is crucial for their survival over time (BarNir and Smith, 2002). The network is an essential organizational model for small and medium-sized enterprises to defend themselves from strong competitive pressures, thus overcoming the limited resources and knowledge that characterize them (Park and Zhou 2005; Valeri, 2016).

In other cases, networks are not created to avoid competitive threats but to improve the competitive position of singular businesses (Park and Zhou, 2005). In this way they are able to seize market challenges they could not face on their own.

A basic prerequisite for the creation and the development of networks is the mutual trust between the parts. Trust is crucial to ease relations between partners (Gulati and Singh, 1998). In inter-organizational relationships, trust presupposes not only the correct behavior of the participants but also the confidence in the competence of the counterparty (Das and Teng, 2002). The interaction is facilitated when trust between participants has been already proven by prior experience of collaboration (Powell, 1990; Gulati and Singh, 1998).

The case of businesses owned by immigrants in the Italian context, along with the concept of "diversity" which characterizes the typical features of an immigrant enterprise, continues to be the subject of national and international scientific debate (Chaganti and Greene, 2002; Horwitz and Horwitz, 2007; Carter and Mwuaura, 2015).

The concept of "diversity" has been analyzed in several respects, taking into account the nature and the type of activities carried out by immigrant companies. Ethnic traditions, ethnic role models, and community ties represent aspects on which the nature of activities carried out by immigrant businesses are based (Rath, 2000; Smallbone et al., 2005; Rusinovic, 2007). These aspects have their origin in the immigrant entrepreneur communities and they tend to be significantly different from those typical of an occidental company.

In fact, the marginality of services, the poor organizational structure, the lack of managerial and language skills often tend to increase the gap between immigrant and local enterprises (Butler and Kozmetsky 2004). The condition of "economic disadvantage" in which immigrants live is an important element of diversity among the immigrant enterprise and the native enterprise (Levie, 2007). Unlike the native-born population, the immigrant entrepreneur has limited access to formal consulting network and difficulties in finding information, and evaluates market opportunities (Kloosterman, 2010).

The same condition of economic disadvantage influences the choice of the sector in starting the entrepreneurial activity (Zhou, 2004). The immigrant entrepreneur is attracted to markets that are accessible with limited capitals, where technological barriers are low, where enterprises are small sized. These markets are overlooked by local entrepreneurs because they guarantee lower profit margins and expansion potential lower than the national average (Rath and Kloosterman, 2000).Considering their ethnic specialization, these companies tend to produce goods and deliver services intended primarily for consumers belonging to the same ethnic community.

In fact, thanks to a number of factors such as the knowledge of the language and customer preferences, the ease of access to imported goods, the availability of manpower resources at low cost and informality in economic and labor relations, it is possible to create business opportunities for micro and small sized businesses by using limited start-up fixed costs, as well as having the guarantee of being protected from potential competition of indigenous enterprises.

These immigrant enterprises can get typical resources and enable social and economic relations in the origincommunities (Rath, 2000; Rueda-Armengot and Peris-Ortiz, 2012). Moreover, especially in the start-up phase, the opportunity to enjoy economic relations within an extended social network represents a stimulus to business initiatives (Kloosterman and Rath, 2001).

Therefore, by sharing group resources and developing economic co-operations, the ethnic group becomes an important tool that facilitates access to information and to economic resources which may not be found in other contexts (Watson et al., 2000; Masurel et al., 2002).

Despite most of the literature considers the immigrant enterprises as characterized by an effective structural homogeneity and devoid of strategic differentiation, in the last few years immigrant entrepreneurs have made entry into sectors that produce goods and services destined mainly to local markets (Waldinger, 2000; Kloosterman, 2010).

The search for new business opportunities has led immigrant entrepreneurs to step outside the ethnic network, activating a series of relationships with other entrepreneurs and territorial Institutions (Masurel et al., 2002; Wang and Altinay, 2012). It would be thus possible to reduce the risk of slow growth and slow development of immigrant enterprises.

Consequently, the strategic and organizational profile of immigrant enterprises becomes more similar to the native companies because of the quest for independence, the desire to move away from subordination and the need to carry on investment projects.

The immigrant women entrepreneurs: A growing phenomenon

The contribution of immigrants to entrepreneurial initiatives in our territory should not be underestimated. In 2015, Italy had approximately 6,041,187 businesses out of which 524,674 were businesses run by immigrant entrepreneurs (8.7% Italian enterprises, 12.9% Italian sole proprietorships), (Unioncamere/Infocamere 2015). Immigrant enterprises are mostly micro or small sized and together they contribute for 6.5% to the national gross domestic product (GDP) with over 94 billion euros (Rapporto, 2015).

In Italy, sole proprietorships are the major component of immigrant entrepreneurship. Immigrant sole proprietorships are 421,004 units (8% immigrant enterprise, 51.4% sole proprietorship). The trade sector has the largest number of immigrant companies, representing 35.8% of all companies, the construction sector has 24.3% of companies, manufacturing represents 7.4%, the business services sector 5%, and finally 2.4% is the share of the agriculture sector which seems to be the least attractive due to high necessary investment costs (Unioncamere/Infocamere, 2015).

From the geographical location point of view, Northern Italy has the highest concentration of immigrant businesses (about 51.2%); there, the most attractive sector for immigrant entrepreneurship is represented by the construction industry. South-central Italy hosts 26.7% of immigrant businesses mainly working in the commerce sector. Regions with the highest percentage of immigrant businesses are Lombardy (19%), Lazio (12.8%), Tuscany (12.1%) and Liguria (11.2%). Milan and Rome record 8.6 and 10.9% of immigrant enterprises respectively.

The 49.2% of immigrant businesses is of Chinese nationality, and it is mainly concentrated in the manufacturing sector, 28.2% is of Moroccan nationality, 10.2% is of Bangladeshi nationality and works in the trade sector, 27.6% is of Romanian nationality, 20.4% are Albanians and work in the construction sector. Different market destinations lead to different activities and productions by immigrant businesses: about 58% of them places products at local and provincial levels, less than 25% places products on regional market and the remaining 17% allocates its products on domestic and international markets. There are 15,065 foreign women entrepreneurs in Italy, equal to 16% of the total run by men. The majority of women entrepreneurs is in the commercial sector (6,966), in the service sector (2,717) and in the textile and clothing sector (2,271).

Managers are mostly women in the hotel and restaurant industry (43%), in the textile and clothing sector (38%) and in the service sector (33%); there are fewer women in the areas of trade(18%) , transport (8%) and in the production and processing of metals (7%); women are virtually absent in the construction industry (just over 1%). More than one-third of women involved are venture partners: they are 37% of the total. The presence of women among immigrant entrepreneurs is growing: 9.3% of companies are run by women (121,000 units) while 8.5% are headed by men. There are approximately 90,300 foreign women-owned businesses in Central and Northern Italy and they represent 11% of all enterprises run by women of the area (Rapporto Impresa in Genere, 2016).

According to Censis report (2016), over the last five years, the immigrant women businesses increased by 3%. The Chinese community has the largest number of women involved in entrepreneurship, with more than 10,000 female managers. One of the biggest immigrant community in Italy is of Albanian origin; according to Unioncamere Observatory data, in Italy 48% of Albanian immigrants are women and almost 3,600 companies are headed by women, i.e. 12% of total Albanian businesses, ranking as the fifth community with the largest number of female managers in the immigrant women enterprises in Italy.

From a territorial point of view, the highest concentration of immigrant entrepreneurs is in Southern Italy (3.2% versus 2.6%) and this is particularly noteworthy in Abruzzo, which has the highest proportion of women entrepreneurs (6.2%). Regarding the age, the largest share of immigrant women entrepreneurs is between 30 and 49 years old (49% of the total female population, with an increase of 0.2 percentage points compared to 2015).

The number of entrepreneurs aged 50 to 69 years has slightly decreased (from 34.9 to 34.7%), while women over 70 years old has increased their number becoming 9.4% of the total individual "pink" companies. The region Campania leads the regional rankings, with more than 8 thousand companies led by young women that, in this case, come to represent 9.2% of the company owners registered in the territory.

Rome and Naples are the cities where most young women choose to become entrepreneurs. However, the highest percentage of young businesswomen is recorded among immigrant women. In June 2015, young female immigrant entrepreneurs represented 12.6% of 52,000 owned by immigrant women in Italy (Unioncamere, 2015).

In some ethnic groups, the participation rates among women are slightly higher than among men: in the case of Nigerians, the percentage of women on total enterprise owners exceeds 50%, while in the Chinese and Brazilian communities the percentage reaches 36%, in the Peruvian community it is about 28%.

However, the weight of female entrepreneurship is significantly below the average of the whole of the countries of origin (16%). Actually, in some communities entrepreneurship is heavily male: this is the case of the Macedonians, Pakistani, Senegalese, Egyptians, Tunisians, Albanians and Bangladeshis where the percentage of women among business owners is comprised between 2 and 5% (Rapporto Idos, 2015).

The survey was carried out by submitting a questionnaire to a target sample of women immigrant entrepreneurs operating in the textile and clothing sector in Italy. This particular economic segment was chosen because it represents the third biggest sector for the number of female immigrant entrepreneurs (with 2,271 enterprises), 16% of the total of entrepreneurs operating in Italy.

The context under analysis is characterized by micro-sized companies. The interviewed entrepreneurs were aged between 30 and 49 years. The questionnaire was submitted in September 2016 and the return of completed questionnaires by e-mail was agreed for the month of December 2016. The sample selection was made possible by consulting primary sources such as ISTAT, Confcommercio, INPS, CCIAA, Censis, Osservatorio di Genere, Osservatorio IDOS.

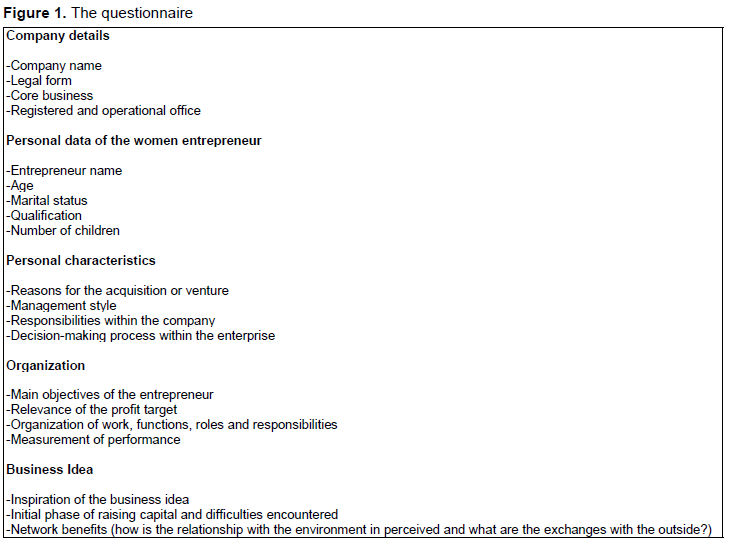

The rate of adherence of respondents was 35%, with 795 com-pleted questionnaires compared to 2,271 submitted questionnaires. The questionnaire was structured in a battery of questions, mainly multiple choice, simple and graded, with a specific weight to be assigned to each response. The questions were aimed at analyzing the distinguishing factors of the enterprises of the investigated sample (Figure 1). All these aspects are summarized in the following aspects:

(1) Personal characteristics of the woman entrepreneur

(2) Organizational aspects and style of leadership

(3) Task environment in which the company operates

The analytical form of the questionnaire was not a constraint for the interviewer to use rigid forms of dialogue with women entrepreneurs: they were free to describe the company's results, focusing on specific aspects which characterize their business experience. The aspects that are analyzed in the questionnaire are the result of the continuation of previous researches carried out in recent years on women's businesses. These are conceived as factors that characterize the immigrant female enterprises and which delineate the distinctive features compared to the male gender (Paoloni, 2011; Valeri and Paoloni, 2016).

The survey has made it possible to analyze typical factors of a female immigrant business, with particular reference to:

(1) The personal characteristics of the entrepreneur

(2) The organizational aspects and style of leadership

(3) The task environment in which the business operates.

These aspects will be discussed later in the paper, taking into account the statements made by the interviewed entrepreneurs, in order to investigate whether there is a possible model of success for the development of women’s entrepreneurship in Italy, in particular as far as immigrants are concerned.

The identikit of an immigrant woman entrepreneur

The identikit of immigrant women entrepreneurs does not vary greatly from that of Italian ones, and includes opposing elements which coexist. The survey shows that immigrant women entrepreneurs are conventional but, at the same time, innovative and dynamic. They are traditional and conservative, but also modern and explorer. For them, success consists of a mix of personal characteristics as, for instance, the ability of taking on responsibility (for 44.7% of them). Relations with employees highlight the style of management adopted.

‘’In women’s enterprises, there is a greater tendency to delegate others than in men’s enterprises’’.

It is interesting to note the ease of integration between women, who tend to be less hierarchical and to build circular relationships. Women tend to be more collaborative than men in the management of roles in the company and women entrepreneurs tend to have a greater focus on the customer’s needs.

Service quality (55%) and customer service (37%) represent strengths that female entrepreneurs add to their business model. Women are successful and suitable for management positions because they possess features such as empathy, sensitivity, creativity, attention to details, ability to listen, ability to negotiate, spirit of collaboration and ability to communicate and more.

Moreover, women entrepreneurs choose to adopt development strategies that are compatible with the preservation and enhancement of the environment, focusing their attention mainly on waste management, choice of raw materials and energy saving.

An interesting outcome of the survey is the development of the figure of ‘’circulating’’ business women, who leave their country of origin to trade in small scale through the sale of their local products in Italy. This phenomenon is particularly widespread within the immigrant community, allowing the entrepreneurs to provide employment to women in the country of origin, helping them combine paid work with family responsibilities, letting them chose when to move and giving them a valid motivation for traveling.

Through the exchange of goods, a cultural exchange takes place too, transforming families and societies according to the different contexts in which the business operates. Among the women contacted during the study research, the majority of those involved in this virtuous circle were from Morocco, Turkey and Albania.

Organizational aspects and leadership style

Organizational aspects and leadership style of women immigrant entrepreneurship are very complex, because of the presence of many intervening factors: different motivations, different strategies for reconciling, different career paths, different personal and professional experiences, which can profoundly affect their life choices.

Interestingly, in the available literature, we find different approaches to women entrepreneurship. It could be read as a response to the stiffness of economy; on the other hand, recent studies suggest that the choices of immigrant women entrepreneurs generally lie in the subjective importance of the desire for autonomy and self-determination.

Analyzing the results of the survey, it has been possible to identify a number of different immigrant women entrepreneur’s profiles, such as:

(1) Traditional profile (53%); which includes women heavily involved in the roles of both manager and housewife, whose motivation is mainly linked to economic factors;

(2) Radical profile (31%), women who do not totally identify with both roles, driven by a desire for personal gratification and ideological factors;

(3) Innovative profile (16%), entrepreneurs who use their company to develop their working lives. These are generally childless women, who express their autonomy through their business. In this case, the desire for autonomy and personal gratification is very strong.

The results of the study survey have revealed no major differences between genders in the adoption of a particular leadership style. Rather, immigrant entre-preneurs believe that it is a personal choice, depending on competencies and that often involves a participatory approach to organizational reality.

«…both men and women have the same competencies: guidelines on how to do business do exist. I believe that the diversity of doing business between a man and a woman lies in the application of the feminine or of the masculine side, from a psychological point of view. What changes is the approach mode».

With regard to the strategies, gender studies show that men tend to prescriptive leadership roles while women prefer a persuasive dimension. Female leadership characteristics can be summarized as follows: interpersonal skills and multitasking know how. Listening, mediation and care are basic components of relational skills. These components are spelled out each day, especially in relationships with customers but also in relations with employees and partners. The natural propensity to motherhood transcends the strictly domestic dimension and becomes a transversal competence.

«.. listening to others is very important, you must always pay attention. If a baby cries, you just can’t ignore it..’’

‘’Being multitasking’’ means having the ability to perform simultaneous multiple actions. The interviews stressed the fact that women are used to having a global view of situations and to managing multiple things at once because of their historical domestic role.

«.. Modern women have the ability to control many things at once. This is very important in any job and in every role, not only that of the leader. Women are very suited to work on several activities at once.’’

Multitasking attitude is a highly functional resource in managing the relationships inside and outside the company because it highlights productivity orientation.

«..women are able to work even under pressure, because of their traditional need to face more than one problem at once. It’s natural for a woman to go back home and take care of the house, the children, the washing machine, and the shopping list!>>

Leading men are more resolute and have a natural tendency to delegate. Wondering whether there is a feminine way of being leaders, we must point out that many of the “objective” skills of leadership come from a history full of male leaders. Therefore, women have few models to refer to and the mentoring practice is still little adopted in their management.

The task environment where company operates

The study reveals two important findings that show the importance of the economic environment in which women entrepreneurs operate: the production context, and the recently settled women's network in the clothing and textile sector.

The production context implies certain production rates and specific requests to workers in terms of working hours: operations often require continuity so the activities must necessarily be organized in shifts. It seems clear that in the working organization, best practices should be applied in accordance with the requirements of production.

Over the years, the consolidated industrial workforce has been mainly composed of men; women are fewer in number due to the limited access to employment and it is harder for a woman to emerge with business initiatives.

However, the situation is different in the tertiary sector, where the manufacturing activity is different and women have more chances.

The interviewed women have focused on the importance of local context and culture, highlighting the reluctance that still persists today when we talk about female leadership.

«.. the working world is not accustomed to having you inside..»

«..in Germany, they have chancellor Merkel. Do you think Italians might accept a female president?..»

According to the interviewed women, the local context is a significant variable although it is perceived more as a constraint than an opportunity for their careers. The survey provides a number of critical elements, such as:

(1) The lack of adequate services, in particular those related to family and mobility;

(2) The permanence of stereotypes and a widespread attachment to traditional gender roles;

(3) The lack of social recognition of women's work;

(4) A business culture that still has its roots in tradition and is unwilling to change.

Perhaps in reaction to this rigidity, female immigrant entrepreneurship is supported by associations which promote the circulation of good practices, initiatives and projects, and that represent the interests and common issues of the associated towards local institutions.

We must also mention the committees for immigrant women's entrepreneurship which were set up at the Commerce Chamber, involved in the organization of information and training meetings about business opportunities for women.

«.. my colleagues and I set up this group, and then many other women entrepreneurs joined us…it is something that really belongs to us.. »

«.. we must stimulate political institutions! »

«.. no man has ever fought for the legislation on maternity. Instead, our group is working on that.. I am also part of an international network working on those same aspects, exchanging tools with Germany, which is more advanced than our country. »

«.. networking is important..I love connecting people because I think every person has something positive to offer and when people meet amazing things can happen’’.

The answers of the interviews show the large number of women entrepreneurs who try to escape from the isolation of the productive context with laborious relational activities. The interviewed entrepreneurs are part of a dense network of formal and informal relationships that are able to enrich the intellectual and social capital of businesses, stimulating new synergies between enterprises and territory and promoting greater awareness among themselves.

The study aims to verify whether there exists a successful model for the development of immigrant women’s entrepreneurship in Italy.

Despite strong similarities with the traditional micro and small enterprises in the Italian native business, immigrant entrepreneurship and, in particular, immigrant women’s entrepreneurship, has a number of specific charac-teristics. Those are related to the migration experience of the entrepreneur and to the rigidity of the economic system in which immigrant companies operate (Light, 2005; Reyneri, 2007; Ndofor and Priem, 2011).

Therefore, alongside constraints related to the profile of an immigrant entrepreneur, it is possible to identify a number of obstacles that limit the consolidation of immigrant business development. There are obstacles inherent in the immigrant's personal sphere, such as:

(1) Difficulties of integration in the economic and social context: It is not easy to overcome the relative isolation condition that characterizes immigrant companies. The company not only represents an activity of production of goods and services but, in contrast, it contains all the entrepreneur's experience. The migratory experiences, the prospects of integration, the ties with the country of origin are not just traits of entrepreneur's personal life but also contribute to connote the company and influence the strategic choices. The importance of corporate social dimension is particularly evident during the growing process when a multiplicity of relationships within and across enterprises is fundamental to establish. In addition, the relationships activated by ethnic groups are very important: these are considered indispensable, especially in the start-up phase;

(2) Difficulty in starting relationships: Immigrants fail to have confidence in the other participants of the economic sector they have chosen because of difficulties of the migratory path and the precarious living conditions in the host country. At the same time, the existence of widespread distrust of the immigrant entrepreneur by the host territory people should be highlighted (Siqueira, 2007; Roy et al., 2008). Often, the linguistic gap generates closure and results in a real obstacle to access to useful information for business development. In addition, there are limited links with other companies in the sector and business associations. This inevitably generates an underutilization of the potential relationship baggage owned by the entrepreneur.

The obstacles related to the rigidity of the economic system in which immigrant entrepreneurs operate, such as:

(1) Legal constraints for the regularization of the personal position of immigrant entrepreneur in the host country: Current legislation imposes a series of obligations to entrepreneurs who need to regularize their legal position in the host country. Often bureaucratic rigidity lengthens waiting times, for example for the renewal of the residence permit. In the absence of such a document the entrepreneur does not have its own legal identity and consequently, does not have the ability to perform actions necessary for the conduct of business(for example signing of contracts);

(2) Legal constraints for the start of business: Depending on the legal form chosen and the business sector in which they decided to operate, a series of requirements are necessary, especially for an immigrant. Often the constraints imposed by the bureaucracy generate delays in the start of business with inevitable economic and financial repercussions;

(3) Poor coordination among people working in support of immigrant entrepreneurship: For the immigrant entrepreneur, confusion and lack of coordination make it even more difficult to seize the opportunities offered by the territory. Furthermore, discriminatory attitudes and behaviors towards immigrants are widespread;

(4) Difficulty in accessing credit: The access to the credit market is one of the major obstacles for immigrant entrepreneurship. Economic resources are already scarce because of the economic crisis, and decrease when the potential entrepreneur is an immigrant. This is justified by the "lower reliability" resulting from the difficulty of providing guarantees in dealing with the credit system.

(5) The obstacles inherent in the entrepreneur's personal sphere immigrant as well as those related to the rigidity of the economic system cannot be underestimated. On the contrary, they should be addressed by strengthening the network of relationships to improve the competitiveness of the business sector.

The concept of networking has long been the object of intense scientific debate in management literature. The network bases its success on the ability to establish cooperation and coordination relations (Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven, 1996) and to foster the joint execution of production processes and delivery of products and services (Gulati, 1998).

By sharing resources and knowledge, network allows overcoming the limitations related to the micro and small size that hinder the development of enterprises in many economic sectors. Organizational literature has analyzed the concept of network focusing on the potential of organized inter-relationships (Greve and Salaff 2003).

In particular, these studies have provided arguments about the causes and benefits inherent in their formation and their implementation (Lorenzoni and Lipparini, 2000; Grandori and Giordani, 2011), focusing on cooperative and competitive strategies activated between the actors involved in the network, on conduct of business rules, on network institutionalization levels, on the power relations and the changes in these variables over time. Nevertheless, to date, a specific analysis on the complex dynamic that drives the inner development processes of collaboration between immigrant and native businesses still lacks (Fadahunsi et al., 2000).

Generally, it is argued that the start of business by immigrants presupposes the establishment of a network of relationships with all actors involved in the territory, such as:

(1) Ethnic groups: These are communities in which there is a strong sense of common identity between members (language, culture, tradition and historical memory). Ethnic groups traditionally live in the same territory and represent the first instrument available to potential immigrant entrepreneurs for the procurement of all that may be necessary for their business (Siqueira, 2007). On one hand, ethnic groups are a valuable source to draw on financial, economic, human resources useful information to start new ventures; on the other hand, they may represent obstacles for growth and consolidation of immigrant businesses in the market and in the not-ethnic environment.

(2) Business associations: They play a very important role in supporting immigrant entrepreneurship. For example, they are engaged in the promotion of specific programs and initiatives that tend to the defense and to the social-economic assistance, in the promotion of educational programs for immigrant entrepreneurs, in the organization of specialization courses, retraining and vocational training for manager and workers. Yet today, there are still few immigrant entrepreneurs who are turning to them and this is why the effectiveness of their activities remains limited;

(3) Investment credit: The banks affect the start-ups of immigrant businesses. Considering the difficulties for immigrants to have access to credit, most of the lenders decided to initiate programs for the provision of micro-credit services for immigrants and their families, without asking them for specific guarantees, aware of the strong dynamism of immigrant entrepreneurship in our country. Nevertheless, ethnic groups are still the preferred source of economic resources.

In this perspective of network analysis, immigrant entrepreneurs are not conceived as isolated entities of the context, but may represent the central node in a larger network of relationships activated with all the actors involved in the environment.

Is there a successful model based on cooperation for the development of immigrant women’s entrepreneurship in Italy?

This study analyses both the factors that affect the development of immigrant women businesses in Italy, and the obstacles that immigrants face to consolidate their business development.

The research shows that the quest for independence, the desire to move away from a condition of hierarchical subordination, the desire to carry on their investment projects make immigrants businesses more and more similar to native businesses, both from a strategic and an organizational perspective.

The survey shows that immigrant entrepreneurship is an important resource for the growth of our territory: although it may represent a big threat for national companies, It is a great opportunity for integration with native businesses to strengthen the competitiveness of the national economy. Considering the importance of immigrant entrepreneurship phenomenon and its contribution to the national GDP, Institutions should not underestimate the importance of the phenomenon and should respond appropriately to support development and consolidation of these businesses.

The interviews have revealed that immigrant women entrepreneurs have yet to get a full view of using social media strategies to promote their own activities. Keeping acting like this, they will not be able to understand that the web is a source of income and visibility and a tool to find new customers and retain existing ones.

Furthermore, the difficulties of the migratory path and the precarious living conditions in the host country cause a lack of confidence in immigrant women entrepreneurs in relations with the other actors involved in the development of business. At the same time, discriminatory attitudes and behaviors towards immigrants are often widespread in the host country.

In many cases, the difficulty of speaking a foreign language generates closure by the interlocutors resulting in a real obstacle to access to information needed for business development. In addition, there are limited links with other companies in the same sector and with business associations; this inevitably generates an underutilization of the potential wealth of reports available to the immigrant entrepreneur.

Therefore, despite the desire to move from a working position of hierarchical subordination to an autonomous position (like that of the entrepreneur), despite the desire of independence and enhancement of the entrepreneurial aspirations, it seems that as yet there is no talk of the existence of a development model of immigrant women’s entrepreneurship in Italy? It is evident that the social-economic disadvantage in which immigrants live is one of the negative conditions that stimulate the search for change.

The study intends to fill a gap in the existing management literature about the study of factors affecting the propensity to start entrepreneurial activities by immigrants, and orient, in this sense, the decision-making processes of the institutions in order to strengthen the competitiveness of the Italian entrepreneurial system.

In future researches, it would be important to study the national profile of immigrant entrepreneurs and examine some empirical evidence of immigrant entrepreneurship successfully launched in Italy, focusing on the analysis of the network’s process of creation and collaboration development among immigrant businesses and indigenous realities.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Alder P, Kwon S (2002). Social capital: prospects for a new concept. Acad. Manage. Rev. 27:17-41.

|

|

|

|

Aviram A (2009). Socialization for entrepreneurship: the second generation. J. Dev. Entrepr. 14(3):311-330.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

BarNir A, Smith K (2002). Interfirm Alliance in the Small Business: The role of Social Network. J. Small Bus. Manage. 40(3):219-232.

|

|

|

|

Butler JS, Kozmetsky G (2004). Immigrant and minority entrepreneurship Praeger, Westport.

|

|

|

|

Carter S, Mwaura S (2015). Barriers to ethnic minority and women's enterprise: Existing evidence, policy tensions and unsettled questions. Int. Small Bus. J. 33(1):49-69.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Chaganti R, Greene PG (2002). Who are the ethnic entrepreneurs? A study of entrepreneurs-ethnic involvement and business characteristics. J. Small Bus. Manage. 40(2):126-143.

|

|

|

|

Clydesale G (2008). Business immigrants and the entrepreneurial nexus. J. Int. Entrepreneurship 6:123-142.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Das TK, Teng BS (2002). The dynamics of alliance conditions in the alliance development process. J. Manage. Stud. 39(5):725-756.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

De Clercq D, Honig B (2011). Entrepreneurship as an integrating mechanism for disadvantaged persons. Entrepreneurship Regional Dev. 23(5-6):353-372.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Dickson P, Weaver KM (1997). Environmental Determinants and Individual Level Moderators of Alliances. J. Bus. Ethics 17(9/10):987-994.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Flap H, Kumcu A, Bulderl B (2000). The Social Capital of Ethnic Entrepreneurs and their Business Success. In: Rath J (ed) Immigrant Businesses and their Economic, Politico-Institutional and Social Environment, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, Macmillan Press.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Gulati R, Gargiulo M (1999). Where do inter-organizational networks come from? Am. J. Sociol. 104(5):1439-1493.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Gulati R (1998). Alliances and networks. Strateg. Manage. J. 19:293–317.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Gulati R, Singh H (1998). The Architecture of Cooperation: Managing Coordination Costs and Appropriation Concerns in Strategic Alliances. Admin. Sci. Quart. 43:781-814.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Horwitz SK, Horwitz IB (2007) The Effects of Team Diversity on Team Outcomes: A Meta-Analytic Review of Team Demography. J. Manage. 33:987-1015.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Kloosterman RC (2010). Ethnic Entrepreneurship. In: Hutchison R (ed) Encyclopedia of Urban Studies, Thousand Oaks, SAGE Publications.

|

|

|

|

Kloosterman RC, Rath J (2001). Immigrant Entrepreneurs in Advanced Economies: Mixed Embeddedness Further Explored. J. Ethnic Migration Stud. 27(2):189-202.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Labrianidis L, Hatziprokopiou P (2010). Migrant entrepreneurship in Greece: diversity of pathways for emerging ethnic business communities in Thessaloniki. Int. Migr. Integr. 11:193-217.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Levie G (2007). Immigration, in-migration, ethnicity and entrepreneurship in the United Kingdom. Small Bus. Econ. 28:143-169.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Light I, Bhachu P (2004) (eds.), Immigration and entrepreneurship. Culture, capital and ethnic networks. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick.

|

|

|

|

Lin X, Tao S (2012). Transnational entrepreneurs: characteristics, drivers, and success factors. J. Int. Entrepreneurship 10(1):50-69.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Masurel E, Nijkamp P, Tastan M, Vindigni G (2002). Motivations and Performance Conditions for Ethnic Entrepreneurship. Growth Change 33(2):238-260.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Paoloni P (2011). La dimensione relazionale delle imprese femminili. Franco Angeli, Milano.

|

|

|

|

Park SH, Zhou D (2005). Firm heterogeneity and competitive dynamics in alliance formation. Acad. Manage. Rev. 30(3):531-554.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Parkhe A, Wasserman S, Ralston DA (2006). New frontiers in network theory development. Acad. Manage. Rev. 31(3):560-568.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Powell W (1990). Neither market nor hierarchy: network forms of organization. In: Staw B, Cummings LL, Research in Organizational Behavior, Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. 12:295-336.

|

|

|

|

Rajiman R, Tienda M (2000). Immigrants pathways to business ownership: A comparative ethnic perspective. Int. Migration Rev. 34(3):682-706.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Rapporto Idos (2015). Rapporto Immigrazione e Imprenditoria. Idos edizioni.

|

|

|

|

Rath J (2000). Immigrant Businesses and their Economic, Politico-Institutional and Social Environment. In: Rath J (ed) The Economic, Political and Social Environment, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, Macmillan Press.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Rath J, Kloosterman R (2000). Outsiders' business: a critical review of research on immigrant entrepreneurship. Int. Migration Rev. 34(3):657-681.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Rueda-Armengot C, Peris-Ortiz M (2012). The Emigrant Entrepreneur: a Theoretical Framework and Empirical Approximation. Int. Entrepr. Manage. J. 8(1):99-118.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Rusinovic K (2007). Moving Between Markets? Immigrant Entrepreneurs in Different Markets. Int. J. Entrepreneurial Behav. Res. 14(6):440-454.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Saxena G (2005). Relationships, networks and the learning regions. Tourism Manage. 26(2):277-289.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Smallbone D, Bertotti M, Ekanem I (2005). Diversification in Ethnic Minority Business: the Case of Asians in London's Creative Industries. J. Small Bus. Enterprise Dev. 12(1):41-56.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Soda G, Usai A, Zaheer A (2004). Network memory: The influence of past and current networks on performance. Acad. Manage. J. 47:893-906.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Valenzuela A (2001). Day labourers as entrepreneurs? J. Ethnic Migration Stud. 27(2):335-352.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Valeri M (2016). Networking and cooperation practices in italian tourism business. J. Tour. Heritage Serv. Market. 2(1): 30-35.

|

|

|

|

Valeri M, Baiocco S (2012). The integration of a Swedish minority in the hotel business culture: the case study Riva del Sole. Tourism Rev. 67(1):51-60.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Valeri M, Paoloni P (2016). Capitale relazionale e sviluppo sostenibile nelle micro e piccole imprese di servizi. In: Paoloni (ed) Studi di genere: il mondo femminile in un percorso interdisciplinare, Edicusano editore, Roma.

|

|

|

|

Vinogradov E, Gabelko M (2010). Entrepreneurship among Russian immigrants in Norway. J. Dev. Entrepr. 15(4):461-479.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Waldinger R (2000). The Economic Theory of Ethnic Conflict: a Critique and Reformulation. In: Rath J (ed) Immigrant Business: The Economic, Political and Social Environment, Macmillan, Basingstoke.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Wang CL, Altinay L (2012). Social Embeddedness, Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Growth in Ethnic Minority Small Businesses in the UK. Int. Small Bus. J. 38(3):3-23.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Watson R, Keasey K, Baker M (2000). Small Firm Financial Contracting and Immigrant Entrepreneurship. In: Rath J (ed) Immigrant Business: The Economic, Political and Social Environment, Macmillan, Basingstoke, pp. 70-90.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Yin X, Wu J, Tsai W (2012). When Unconnected Others Connect: Does Degree of Brokerage Persist After the Formation of a Multipartner Alliance. Organ. Sci. 23(6):1682-1699.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Zhou M (2004). Revisiting Ethnic Entrepreneurship: Convergencies, Controversies, and Conceptual Advancements. Int. Migration Rev. 38(3):1040-1074.

Crossref

|