Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

Unions are prominent stakeholders in employment relations (ER), representing and protecting the rights of their members and other employees on labour-related issues that the workforce is overwhelmed with within the workplace. The purpose of this article was to examine global unionism to advise South African (SA) Information and Communication Technology (ICT) sector labour unionism. It focuses on the recent trends of global literature review to answer five research questions. The rationale is to gain a more theoretical understanding of union roles, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) conventions, global unionism, SA unionism, SA ICT unionism, union challenges and strategies. Globally, unionism drives advancements in socio-economic policies, calling for social dialogue between the tripartite alliances partners in ER: Unions, employers, and the government. However, SA ICT union leaders are weak when negotiating for equity, socio-economic justice, and the advancement of employees in their careers. This research study revealed that union challenges include poor social dialogue, ineffective strategies to sustain membership, inefficient partnerships, and non-collaboration between management and unions. By the results of this study, a strategic framework was proposed for union effectiveness to provide Human Resources (HR), ER and union leaders with a practical management tool. Thus, this study contributes by expanding the body of knowledge on global and SA ICT unionism.

Key words: Employees; employers; human resources; employment relations; information and communications technology; socio-economic advancement; social dialogue; South African; unionism.

INTRODUCTION

Global unionism is a phenomenon through which interrelations among unions occur; it impacts and influences the socio-economic status of the workforce through social dialogue with relevant stakeholders in the ER sphere worldwide (Debono, 2017). It encompasses global, national, regional, and local labour movements. It is worth noting that some unions, and not all of them, are affiliated with international federations and confederations.

Northrub (2018) defined industrial or employment relations (IR/ER) as an industrial tool that engages management with recognised unions on collective bargaining agreement implementation issues. ER involves the tripartite relationship between employees represented by unions, employers, and government in conjunction with institutions and associations through the process of mediation (Brown et al., 2018). The purpose of ER is to minimise, curb and avert labour disputes that arise between unions and management through the government (Njoku, 2017). Nonetheless, the customary frameworks of ER have been crumbling in countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom due to unsound and unsupportive legal systems. The pluralist approach to ER suggests that interests and rights that include the regulation and quality of work, fairness, and collective voice by government and unions must be studied (Budd and Bhave, 2019).

In the current ER landscape, employees are on a quest for mutual respect with employers. Equity, job satisfaction and security, fair salary, and socio-economic benefits dominate ER and unionism agendas (Goslinga, 2017). Although this is the case, SA unionism and SA ICT sector unionism are both confronted with challenges in the ER arena. For example, union membership has decreased drastically in SA and appears poorly amongst the SA youth (Visser, 2019a). SA unionism is attributable to lower productivity and non-flexible employment contracts that hinder the economic growth that could create jobs (Bisseker, 2017). Comparably, SA ICT sector unionism is also overwhelmed with declining union membership (Visser, 2019a), the effects of globalisation (Chun and Shin, 2018), selfish union leadership (Zlolniski, 2019), and lack of strategy to overcome the fourth industrial revolution (4IR) challenges (Schwab, 2017). These unions fail to resolve socio-economic advancement by collaborating with employers within this sector in a harmonious and peaceful approach (Visser, 2019a). In this regard, this study identified gaps concerning its problem statement that states as follows: SA ICT union leaders are poor when negotiating for equity, socio-economic justice, and advancement of employees in their careers. Therefore, a theoretical exploration of global unionism was necessary to recommend strategic union drivers for the SA ICT sector.

Moreover, labour issues can be managed and achieved in the ER domain, with effective and efficient HR interventions geared to maintain a good working relationship between employers and unions. Wilkinson et al. (2019) stated that HR needs to incorporate policies that ensure employees are treated with respect and dignity, not just as productive tools, to alleviate industrial hostility. Employees are human assets but cannot be susceptible to abuse as just production instruments by management. Globally, employees, employers and governments engage in social dialogue to resolve ER issues that form the basis of IR or ER tasks. Social dialogue includes extensive negotiations and engagements between management and unions on behalf of employees. Government must dialogue about matters of common interests to all the parties involved in economic and social regulations (International Labour Organisation [ILO], 2018). Social dialogue refers to a negotiating forum whereby the stakeholders agree to terms and conditions of their engagements on social policies (The European Trade Union Confederation [ETUC], 2018). Parties involved in ER engagements have different motives and goals that they need to attain.

The motivation for this article is that global unionism is largely unexplored concerning its function in advancing employee rights and growing economies (Wilkinson et al., 2019). In Africa, especially in South Africa (SA), union effectiveness appears to be a contentious issue. This article aims to explore global, African and SA unionism in light of proposing a strategic framework for effective unionism in the SA ICT sector. There are five research questions in this article as follows:

What are union functions or roles?

Are unions effective or ineffective globally?

Are unions effective in the SA ICT sector?

What challenges plague SA unionism and the SA ICT unions?

What strategic framework is available for effective unionism in the SA ICT sector?

This article theoretically contributes to the body of knowledge on union and ER effectiveness, strategy, and practices in the SA ICT sector. Practically, this article provides HR, ER, union and government leaders and managers a proposed Strategic Framework for Union Effectiveness as a tool for efficient and successful unionism.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The following section aims to answer research question 1: What are union functions or roles?

Union roles in the economy

Union roles include protection and advancement of the economic, social, and political interests for the benefit of their members (Okechukwu, 2016). They play a significant role in the economy by convincing employers to surrender to their demands that boost worker remuneration. Furthermore, unions drive economic policies that advance their member welfare and the community (Okechukwu, 2016). Labour Unions in Nigeria act as agents of socio-economic change to economically develop their members, other workers, and ordinary citizens (Orji and Kabiru, 2017).

As such, unions act as social and economic architects in African countries, as they did and continue to do in other countries and continents. As socio-economic architects, unions need social partners to improve the social conditions and economic performance relative to their countries. Although unions may have lost the power to represent their workforce (Visser, 2019b), they are important actors in crafting local, national, and global economies via their influence and support from numerous international institutions.

Union dysfunctional roles in union membership

The strength and ranking of unions are dependent on their union density in the sectors to which they serve their members (Currie et al., 2017). Employees align themselves to labour movements to protect themselves against victimisation by exploitative employers (Caraway and Ford, 2020). In addition, Currie et al. (2017) argued that member allegiance to unions is contingent on the union power to solve problems to their workplace issues. There is, however, deterioration of union membership in the world, consequential due to the loss of union leadership in their power to bargain with employers, resulting in low salary increases, fewer jobs and fewer benefits (Isaac, 2018). In most parts of the world, the ailing union membership is evident due to the erosion of union bargaining power over decades (Ellem et al., 2020). A decline in union membership is associated with various factors such as the following: unsupportive and uncooperative HR policies, procedures, and practices; management contravention of union rights to freedom of association and collective bargaining; and no clear strategic drive for the recruitment of new union members (Uys and Holtzhausen, 2016).

In Europe, union membership has immensely declined by 79% between 1992 and 2000. It further declined between 2000 and 2017 by 11%, which is the lowest rate this continent has ever experienced (Visser, 2019b). The declining global union membership is also attributable to the massive economic inequality that creates lessened income distributions to the detriment of the growing workforce (Uys and Holtzhausen, 2016). On these grounds, the Power Resources Approach (PRA) questions research studies that accentuate the declining union power and influences that emerged worldwide since the 1980s. The PRA recommends that union members focus on making strategic decisions on who holds the fiscal power; cooperative and harmonious ER; and neoliberal economic policies worldwide (Schmalz et al., 2018).

Union leadership roles in collective bargaining

Collective bargaining has been a crucial tool for unions in industrial economies for longer than a century. It governs how labour markets operate, in addition to protecting and securing employee pay equity. Nyanga and Tapfumanei (2019) assert that collective bargaining through constructive negotiations results in employee engagements to enhance worker performance. The customary framework of collective bargaining is predominantly centralised in most countries. This practice establishes standardised working conditions relative to salaries, working hours, and other remuneration that employees qualify for in different organisations (Bach and Bordogna, 2016). Decentralised collective bargaining involves the negotiations relative to working conditions at the organisational level (Visser, 2016), while centralised collective bargaining takes place at the sectoral or national level.

The attrition of union leadership on collective bargaining power results in a power disparity between the workforce and management (Dromey, 2018; Ryall and Blumenfeld, 2016). Organised labour gains strength through the collectivism of employees against their individualism in the workplace, and effective union leadership uses this power to the advantage of the working class when bargaining with employers (Currie et al., 2017). Despite this, challenges exist in union leadership tasks that include collective bargaining with employers and their roles as unionists, mediation of social relations, involvement in internal union affairs, and the out-turns of globalisation (Chun and Shin, 2018).

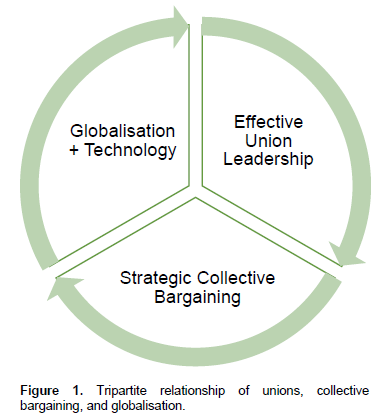

Additionally, union leaders have lost their collective bargaining power due to the outsourcing of jobs in most countries resulting from unfavourable effects of globalisation that impacted sectors of employment negatively (Klindt, 2017). It appears that African countries may be lagging regarding the out-turns of globalisation compared to developed continents that continue to dominate and enjoy the products of globalisation (Asongu and Nwachukwu, 2016). For this reason, strategic labour policies are advocated for African nations to participate and benefit from globalisation, advancing technology and innovation (Asongu and Nwachukwu, 2018). For unions to gain bargaining power in worker participation, contributions and rewards from globalisation, technology and future union trends, union leaders and members must engage in tripartite collaborative collective bargaining. Figure 1 depicts the revolving tripartite relationship between unions, collective bargaining, and globalisation in the technological era.

Unions represent employees in collective bargaining at a local level on sectoral, national, and global matters. In this process, the revolving tripartite relationship involves an effective strategic union leadership that bargains with employers on the positive and negative effects of globalisation and technology. The ongoing responsibility of effective unionism in any country lies in union leadership power to utilise globalisation and technology to advance employee socio-economic development.

Union roles in collaboration for harmonious ER

Collaboration is an approach to industrial peace and productive engagements among employees represented by unions and employers represented by employer organisations to attain their conflicting mandates (Bray et al., 2020). In a productive ER arena, organised labour and management collaborate objectively and harmoniously to achieve their different goals. However, Visser (2019a) demonstrated that poor collaboration between unions and management emerges because both parties disengage when negotiating during labour issues discussions. In addition, the labour-management relationship is hostile irrespective of numerous attempts to advance collaboration through government policies and labour legislation in Europe (Bray et al., 2017). Consequently, the assumption is that unions and employers are counter-interactive because they have different goals and priorities (Martin et al., 2016). Yet, there is room for improvement on the condition that they trust each other and possess the necessary skills and knowledge to engage in effective and cooperative social dialogues (Obiekwe et al., 2018).

HR plays a pivotal role in the ER space between unions and employers. Colombo and Regalia (2016) noted that effective HR practices promoted a healthy and sound relationship between organised labour and management. There is a transparent, better, and harmonious collaboration between employers and union leaders in ER when all negotiating parties completely trust each other (Smith, 2016). Harmonious ER induces a sense of belonging in the organisational workforce, and employees fully take accountability and responsibility for their actions. This practice produces harmonious and peaceful working relationships between management and employees, especially union leaders and officials. In some cases, the establishment of unions has not been desirable in the ER domain. This scenario results in disharmonious working relationships between unions, employers, employees, and managers (Arslanov and Safin, 2016).

In summary, unions play a fundamental role in the ER. Effective participation of labour unions in the economy is indisputable, and effective union leadership engage employers in collective bargaining in favour of their members and other employees. However, some factors hamper union effectiveness, for instance: a shrinking union membership that disempowers labour unions, technology, and globalisation. Finally, this section indicated that for an efficient harmonious working relationship to prevailing between management and organised labour, both parties need to accommodate each other and put their differences aside with HR intervention through their practices and policies. Therefore, this section has provided answers to research question 1. The following part of this study aims to answer research question 2. Are unions effective or ineffective globally?

Effectiveness of international unionism

International unionism is composed of global unions across many countries. The International Trade Union Congress (ITUC) claims a membership of 202 million across 163 countries and regions (ITUC, 2018). Notably, Croatia had 630 registered labour unions in 2016 (Bagi?, 2019) and four union labour federations. In a similar vein, Latvia boasted 197 recognised labour institutions in 2014 that protected employee rights (Lulle and Ungure, 2019). In addition, the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC) covered its affiliated labour organisations from various countries in 2019 that encompassed five from Hungary, four from Romania, three from Poland, and one from Latvia, Czechia, Slovakia, and Slovenia.

Unions are perceived by some researchers as inefficient, while others evidence their effectiveness to effect global change socially and economically. For example, in the United States, 62% and 39% of employees acknowledge and strengthen the influence of unions, irrespective of the view that the rate of union density in this country is moderately low compared to other developed nations in the world (Saad, 2018). Globally, the call is for union effectiveness about collaborative and cooperative social dialogue in the ER space, between employers, unions, and government. Nevertheless, this tripartite application is not spontaneously harmonious caused by different reasons per country. In Portugal, the trust between unions, employers, and the government seems to have broken down. Therefore, no collaboration exists between these ER stakeholders (Addison, 2016).

Ineffectiveness of African unionism

The African continent comprises of the global rapid ballooning workforce that carries an enormous number of an unemployed younger generation. In the Northern parts of this continent, this practice is evident as 30% of the younger generation were unemployed in 2015 (International Labour Organisation [ILO], 2016). It seems a violation of employee rights is rife in some African states in union presence. For instance, in the Central African Republic, Eritrea, Somalia, Burundi, South Sudan, and Sudan: in these nations, labour anarchy prevails because worker rights seem violated (ITUC, 2017).

In most African countries, the institutional power of organised labour is weak because unions have a deficiency in applying the labour legislation efficiently. Tapia et al. (2017) are sceptical concerning union effectiveness in implementing the ILO conventions, citing that unions appear to be aloof in this regard and consequently fail to address this challenge. To aggravate the African situation, Chinese and other foreign companies recruit foreign employees from their employment agencies to work in African multinational organisations. Most Chinese natives prefer to recruit Chinese employees for their skills, language, cultural similarity, and convenience. Furthermore, this practice diverts the labour legislation applicable to a specific African country in which they operate (Cooke et al., 2018). Moreover, African countries trading with China have purportedly adopted the Chinese labour legislation that tends to disregard the protection of workers (Adolph et al., 2017).

In SA, 13.7% of total employment growth between 1995 and 2016 has been created through outsourcing and subcontracting of jobs (Bhorat et al., 2016). Low-skilled workers in SA are prone to insecure jobs that pay unjustifiable salaries and further restricted career advancement (Mncwango, 2016). SA lacks a strategy that creates jobs and neglects the challenge of skills shortages and other labour issues within the current competitive labour market (Bisseker, 2017).

In summary, some global union federations claim capacities in terms of union membership. Yet, studies show that unions are fragile concerning membership across the globe. Also, international unionism advances unity when engaging in social dialogue platforms amongst ER stakeholders (unions, employers, and government). African unionism is deficient owing to its failure to partner with governments to reduce the alarming rate of youth unemployment. It further fails to apply the ILO conventions beneficial to the working class. Moreover, SA has a shortcoming in producing jobs for its unemployed population. The following section aims to answer research question 3: Are unions effective in the SA ICT sector?

SA ER and unionism legislation

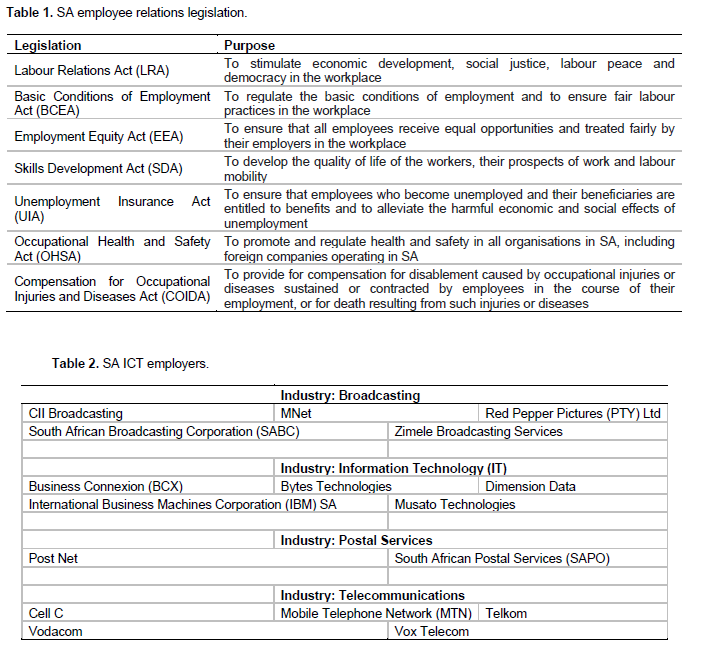

The two major industrial laws that regulate ER in SA are the Labour Relations Act (LRA) and the Basic Conditions of Employment Act (BCEA). In addition to the LRA and BCEA, other regulations that seem to support ER in SA, employee rights, unionism, and harmonious collective bargaining are the following SA legislation: Employment Equity Act (EEA); Skills Development Act (SDA); Unemployment Insurance Act (UIA); Occupational Health and Safety Act (OHSA); and Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act (COIDA). Table 1 presents the various legislation and purposes that govern ER, unionism, freedom of association and collective bargaining in SA.

SA ICT ER

The SA ICT sector comprises employers that render services in broadcasting, information technology (IT), postal services, and telecommunications. Table 2 presents the SA ICT employers. The field of ER in the SA ICT sector has been re-designed to accommodate the changing nature of work, workplaces, and workers. New HR policies, procedures, practices, strategies, and trends are all enacted to advance employee rights (Cook et al., 2020). The operational conditions of both unions and shop-stewards in the SA ICT sector have also changed as technology emerges as the latest threat to labour-intensive jobs (Chun and Shin, 2018). Studies reveal that ICT unions may not be ready to adapt to the rapidly advancing workplace in this technological era. Moreover, it is imperative to note that the fourth industrial revolution (4IR) falls outside the normal scope of union tasks when representing employees in the workplace because members require unions to protect their labour rights against exploitative employers (Prassl, 2018). It seems that 4IR has adverse effects on both unions and employees, as the latter are negatively affected by technological advancement resulting in the former losing union members (Schwab, 2017). Therefore, the future of SA ICT unions in the 4IR era seems to be a challenge (Chun and Shin, 2018).

SA ICT employees may be members of these national unions as follows:

1) Broadcasting, Electronic, Media and Allied Workers (BEMAWU).

2) Communication Workers Union (CWU).

3) Democratic Postal and Communication Workers Union (DEPACU).

4) Information Communication and Technology Union (ICTU).

5) Media Workers Association of South Africa (MWASA).

6) National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA).

In summary, SA ICT sector unions face massive challenges concerning 4IR. This dilemma is disadvantageous to the workforce because it seeks to secure the jobs under threat. Regrettably, labour movements in this sector are deficient in a strategy that reduces and prevents the loss of jobs at issue. Therefore, SA ICT sector unions appear to be ineffective in this regard.

METHODOLOGY

The research method employed in this study was qualitative, involving literature review and document content analysis. An in-depth review of recent relevant literature was collected and used as secondary data. This data assisted in providing answers to the study primary research question. A five-step approach was applied to gather, analyse, and report on the qualitative documents of this study (Fanelli et al., 2020). Step 1 determined the purpose of the literature review and content analysis. The rationale was to understand unionism roles, effectiveness, ineffectiveness, and challenges across a spectrum. Exploring and analysing existing literature before conducting empirical studies allows for a research topic to be explored more holistically, providing a global, continental, national and local view of the context (Gough et al., 2017). Step 2 was an online search and exploration of the following online databases: Google Scholar, Research Gate, SAGE, Emerald Insight, Springer, Wiley Library, EBSCO, JSTOR, Web of Science, and Taylor and Francis. The search covered articles relevant to this study across ER/IR, HR, ICT, Economics, and Business Management. Step 3 determined the criteria for purposively selecting and gathering the secondary data required for this study. The keywords included in the study search criteria were union effectiveness, union members; union leaders; union strategy and challenges; ICT; and South Africa.

Step 4 determined the inclusion and exclusion of articles and legislation. The initial search yielded over 30 000 studies. The search was narrowed down to 8700 articles using the study keywords. Finally, only 180 studies that contained some of the study keywords were relevant. Articles that excluded three or more keywords were not utilised from the final analysis. Step 5 involved a combined document synthesis and content analysis technique to arrive at the last set of articles in this study. These articles were analysed and synthesised systematically to answer the research questions of this study (Snyder, 2019). The references between the years (2016-2021) were employed as cited in this article, and articles that are relevant to this study but older than five years were not utilised. In the final analysis of this study, only 60-70 articles were analysed purposively, from which relevant findings were drawn out. The intensive, systematic literature review, document analysis and synthesis were the most appropriate method for this study because they explored the unionism strategy effectiveness using existing accredited, documented, and published evidence (Pratici and Singer, 2021).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Effectiveness of SA ICT unions

This section presents the exploration into answering research questions 1, 2 and 3. Research question 1 is as follows: What are union functions or roles. The results revealed that labour unions are economically active (Okechukwu, 2016) but failed to sustain union membership (Isaac, 2018). In support of this finding, Ellem et al., (2020) found that dwindling union membership is irrefutable because most unions across the globe are experiencing it; thus, unions and the workers endure drawbacks while management is benefitting concerning the challenge under discussion. Although organised labour participates in collective bargaining, the results further indicate that union leadership experiences difficulties engaging employers in this process (Chun and Shin, 2018). Similarly, unionists have been losing their power over the years to effectively bargain for their members and the working class in general; it appears this situation is perpetual because unions lack tactics to reduce it to maintain their significance (Ellem et al., 2020). Furthermore, the results revealed that unions failed to collaborate with employers for harmonious ER (Addison, 2016; Arslanov and Safin, 2016).

A recent empirical study supports this finding. Wood (2020) asserts that there is no collaboration between employees represented by unions and employers; this is an undesirable custom because these parties frequently interact together to attain their different goals. In contrast, a study found that unions collaborate with management via HR intervention to maintain peace and harmony in the workplace while protecting the interests of their members and other beneficiaries (Cook et al., 2020).

Research question 2 is as follows: Are unions effective or ineffective globally? The answers to research question 2 are two-fold. On the one hand, international unionism is inefficient concerning union membership (Isaac, 2018), a phenomenon that reduces union power to bargain with employers on behalf of their members. A recent study has also highlighted that unions worldwide are experiencing a decline in union membership (Ellem et al., 2020). On the other hand, international unionism is efficient because it calls for HR and ER to promote collaborative and cooperative social dialogue in the tripartite relationship between employers, unions, and government. African unionism is also ineffective about youth unemployment (ILO, 2016) and executing the ILO conventions (Tapia et al., 2017). Consequently, the rate of youth unemployment tends to increase in Africa, as it is highly likely this is one of the reasons the youth are not interested in joining labour unions. Various African countries ratified the ILO conventions. In this regard, African unionism dysfunctionality appears unfair to workers to forfeit their benefits concerning the conventions under discussion.

Research question 3 is as follows: Are unions effective in the SA ICT sector? The answers to this research question are significant: Union membership is vastly diminishing (Schwab, 2017), a factor that weakens unions as they are susceptible to being de-recognised by employers. Also, it appears that organised labour in this sector lacks strategies to resolve this challenge. In a similar vein, Isaac (2018) found that union membership is diminishing in various parts of the globe. SA ICT unions are also ineffective because they failed to regulate the 4IR workplace to protect employees’ right, jobs and advance their skills (Schwab, 2017; Chun and Shin, 2018).

SA unionism challenges

This part of the study aims to answer research questions 4 and 5. Research question 4 is as follows: What challenges plague SA unionism and SA ICT sector unions? Research question 5 is as follows: What strategic framework is available for effective unionism in the SA ICT sector?

In SA, several union leaders practice egocentric leadership because they solicit bribes from employers and accept promotions in exchange for neglecting employees interests; this action is detrimental and amounts to a misrepresentation of the working class (Zlolniski, 2019). In this country, it appears that union membership is very poor, especially amongst the youth. According to Visser (2019a), only 15% of youth are union affiliates compared to a third of the younger generation not associated with unions for all the labour federations in SA. This argument is supported by empirical evidence. Høgedahl and Kongshøj (2017); and Kjellberg (2020) found that unions are poor and failed to recruit young workers, a tradition that also contributes to their inefficiencies as they gain strength through massive membership. Moreover, the youth could bring bright and fresh ideas to take unionism to greater heights. Therefore, it is evident that SA unions are failing dismally to recruit the younger workforce into their labour movements which constitutes a threat for the future of unions in this country (Visser, 2019a). Workers likely partner with unionism on the condition that they value and acknowledge the benefits provided to them by organised labour that needs to maintain its relevance. For instance, Caraway and Ford (2020) opined that labour unions thrive regarding their members challenges in the workplace against toxic management because they have the power to achieve their mandate in the ER space. Opposingly, Klindt (2017) found that unions are powerless and susceptible to failure in serving their members and other workers.

Other factors that negatively affect union density in SA include the changing nature and erosion of permanent employment contracts into temporary employment and labour brokers and slower economic growth that impedes job creation (Bisseker, 2017). As a result, SA experienced an estimated increase of approximately 5% concerning temporary employment contracts between the periods 2011 to 2015 (Cassim and Casale, 2018). Additionally, the SA youth endure an extreme unemployment rate. This undesirable situation is associated with the government and unions as they are fuelling the challenges about the current situation concerning the youth job crisis in SA. Statistics South Africa (StatsSA) (2019) reported that the SA youth unemployment rate is alarming because 68% of black males and 79% of black females were not participating in the labour market.

Union higher wages demands are attributable to the failure to attract foreign direct investment integrated with the government failure to amend its labour legislation that attracts businesses and entrepreneurs to invest in SA (Balsmeier, 2017). However, the SA government attempted to address this challenge by attracting investors by implementing incentive-based strategies. Nel et al. (2016) stated that the current high rate of labour disruptions due to strikes organised by labour unions is counter-effective to the government plan and thus needs to modify its inflexible labour legislation. These strikes are counter-productive to the economic development of SA and have adverse effects on employers operating their businesses in this country (Nel et al., 2016). Additionally, Balsmeier (2017) found that investors are reluctant to risk their capital in highly unionised industries because of increased labour protests and employee higher wages of which both are attributable to lower productivity. Subsequently, Bernards (2017) proposed that unions need to be realistic when negotiating wage increases for their members and other employees to sustain businesses and ensure that the salary adjustments are affordable and not financially draining for SA employers.

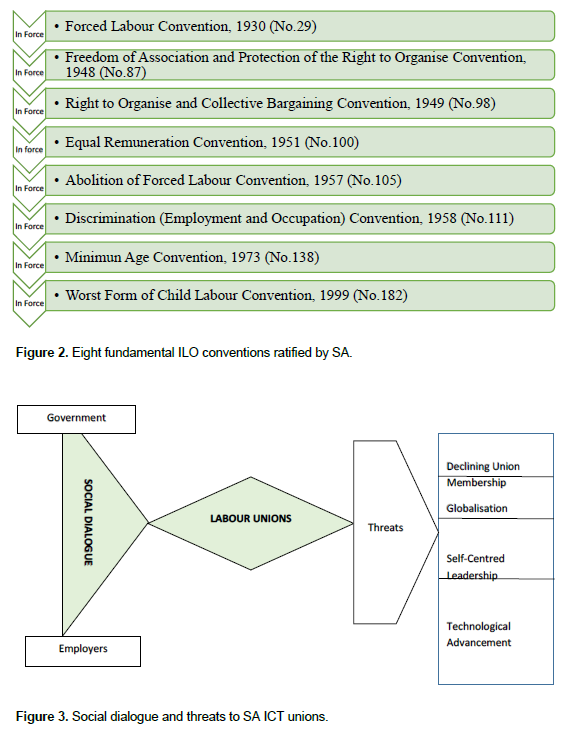

Objectively, management is opposed to union members who have the right to strike under the Labour Relations Act 66 of 1995 (LRA) and thus prefer temporary and independent contractors instead of permanent employees who are potential union affiliates (Coetzee and Screuder, 2016). SA faces socio-economic challenges that include but are not limited to high unemployment, poverty, and inequality due to union ineffectiveness and the government failure in improving labour policies (Madonsela, 2018). Despite all these challenges, SA ratified the ILO conventions. Figure 2 displays eight fundamental conventions ratified by SA.

SA ICT sector union challenges

Recent literature trends reveal that similar to global trends: the SA ICT ER landscape is volatile, erratic, and transformative considering advancing globalisation and technology. The threats of SA ICT unions are declining membership (Visser, 2019a), globalisation (Asongu and Nwachukwu, 2016; Chun and Shin, 2018), self-centred leaders (Zlolniski, 2019), and 4IR (Schwab, 2017). The inability of these unions to engage, dialogue and successfully become economic architects and resolve employee socio-economic demands through collaborative dialogue presents a further challenge (Visser, 2019b). Conversely, another study found that unions play an integral part in their country economies in which they operate (Okechukwu, 2016). Nevertheless, the unionism gap of non-cooperativeness needs to be closed in the future to promote industrial peace and harmony in the SA ICT ER realm (Tapia et al., 2017). Figure 3 depicts the process of social dialogue and other factors that are threats to SA ICT unions.

Figure 3 illustrates that threats to unions include: a decline in union membership, globalisation, self-centred leadership, and technological advancement as indicated by the connection between partners. It further displays that the significant role players in social dialogue are unions, employers, and government. In this process, unions are workers’ representatives, government promulgates labour legislation, and it also mediates, conciliates, and arbitrates between unions and employers where applicable (ILO, 2018; Schmalz et al., 2018). Other employers choose to be affiliated to and thus are represented by employers’ associations, while others prefer to represent their own interests in the ER space as individual businesses.

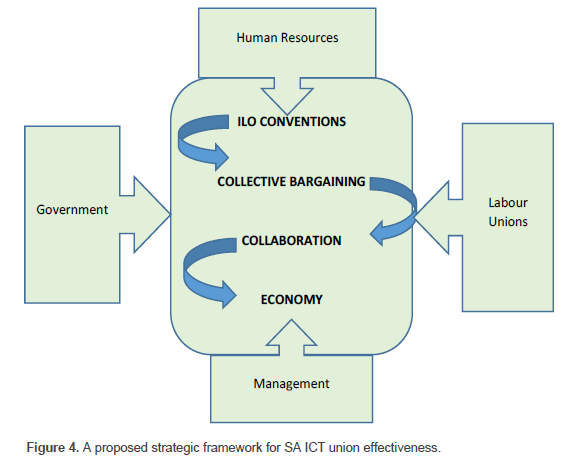

Unions need to address the factors that threaten their effectiveness to remain relevant in the ER domain. Firstly, they need to resolve the declining union membership that weakens them. Secondly, these organisations need to utilise globalisation to their advantage rather than perpetuate to view global connectivity as a threat. Thirdly, union leaders should design and drive effective and efficient strategies to manage technological advancements. Finally, unions need to address the issue of their self-centred leadership. Figure 4 presents the proposed strategic framework for union effectiveness in the SA ICT sector.

Figure 4 presents that the ILO conventions as per ratification by the government are the foundation for collective bargaining whereby recognised unions negotiate for their members and other employees with employers. In turn, stakeholders in this process are unions, management, and government (through enforcement of labour legislation) by conjunction with HR (through the implementation of sound labour policies) must lead to collaboration between employers and unions. Finally, this interaction between ER stakeholders can improve the SA ICT sector and the ailing economy of SA to benefit the employees of the ICT sector and the country (Huws et al., 2017). In this regard, an efficient and harmonious social dialogue, collaboration, and sound union tripartite partnerships (with the union, management, government) should be monitored and evaluated by HR and ER managers and professionals.

Union collaboration and cooperativeness must aim to advance their membership, socio-economic benefits, create career paths, transform jobs, and grow the economy in rural, suburban, and urban areas (Currie et al., 2017; Saad, 2018).

In summary, answers to research question 4 are as follows: What challenges plaque SA unionism and SA ICT sector unions? SA unions are troubled with decreasing union membership, particularly the youth (Visser, 2019). In this country, unemployment is a genuine challenge for unions and the government. This problem is a challenge on labour movements because it harms union membership. The failure by the SA government to create employment opportunities is another factor that impedes an improvement in union membership as some of the new entrants in the labour market could be potential union members.

Also, SA unions have massive challenges because they contribute to prolonged strikes that hinder production integrated with their demands for higher wages that are a barrier to foreign direct investment (Nel et al., 2016; Balsmeier, 2017).

The challenges experienced by SA ICT sector unions include: a shrinking union membership (Shwab, 2017; Visser, 2019a), this is the trend also experienced by unions around the globe, union leaders in this sector lack social dialogue skills and fail to form progressive tripartite relationships (Visser, 2019b), and lack strategies for effective management of globalisation, 4IR in the changing world of work (Schwab, 2017).

In summary, the answer to research question 5 is as follows: What strategic framework is available for effective unionism in the SA ICT sector? A call is made for union leaders to use the proposed strategic framework as a tool for effective collective bargaining with partners via strategic dialogue, discussions, and agreements. Therefore, answers have been provided for research questions 4 and 5 of this manuscript. From now onwards, this study proposes the following practical recommendations for the effectiveness and social partnership of SA ICT unions to consider:

1) Smaller unions within this sector should consider amalgamating with larger unions to form better and stronger unionism.

2) Unions need to maintain their relevance by addressing the reduction of union membership by applying the attract and defend strategy. In other words, they need to preserve their current membership and attract new members by displaying tangible evidence of their worth.

3) Unions further need to appoint the youth in their ranks to improve the status quo of the latter being disinterested in joining the labour movement.

4) Recognised unions could further enforce an agency shop agreement according to section 25 of the LRA through a collective agreement with employers. This measure might indirectly force some non-union members to join the labour movements because they would be paying an agency fee in any case.

5) Harmonious collective bargaining by unions must advance both employees and employers for the economy to grow, transform and evolve via globalisation and 4IR.

6) HR and ER managers must facilitate harmonious employer and union collaboration, cooperation, and agreement for the socio-economic development of all employees across all occupational categories.

7) Union leaders, managers, officials, and members must aim for successful partnerships, negotiations, and agreements by identifying and managing union challenges, threats, and gaps, and

8) Union leaders and managers should implement effective strategies to achieve targeted goals and annually advance employee socio-economic statuses in the SA workplace.

Practical implications of effective union strategy

Strategic and effective unionism can benefit employees and employers in various ways. The following are a few practical implementation strategies recommended for union leaders and officials:

1) By negotiating salary increases for their members and other employees, they expand the buying power of the workforce as consumers of goods and services. Resultantly, businesses benefit and in turn contribute to the economy.

2) Unions secure training and development of the working class, a practice that also advantages businesses because skilful and competent employees contribute to the bottom line of their employers.

3) Unions also ensure that employees are not prone to unfair dismissals by manipulative employers. This action is also advantageous to businesses because they avoid unnecessary labour disputes against them by victimised employees.

4) Unions represent employees in ER hearings to protect their jobs, an undertaking that is also favourable to businesses because they save money on recruitment costs to replace dismissed employees.

5) Unions safeguard the compliance of employers on labour legislation promulgated by the state. Therefore, businesses avoid possible penalties that would have been imposed on them by the state for non-compliance with labour regulations.

6) Unions further secure the health and safety of employees, a measure that also advantages businesses because the rate of absenteeism becomes minimal, and employers are likely to attract their ideal workforce as employees prefer a safe working environment and

7) Union followers are susceptible to being easily persuaded by union leaders because they trust them. Therefore, businesses can benefit by allowing unions to act as change agents in conjunction with HR.

CONCLUSION

The first significant finding of this study is that diminishing union membership is evident across the globe (Isaac, 2018; Schwab, 2017; Ellem et al., 2020). The second significant finding of this study is that poor union membership amongst the youth in SA is experienced (Høgedahl and Kongshøj, 2017; Kjellberg, 2020; Visser, 2019a). The third significant finding is that union leaders have lost the power to bargain with employers (Chun and Shin, 2018; Ellem et al., 2020).

However, the analysis of Caraway and Ford (2020) contrasts with this finding. These scholars found that unions possess the power to represent and protect their member interests in the workplace. Lastly, poor collaboration between employers and employees exists (Arslanov and Safin, 2016; Wood, 2020). Contrarily, Cook et al. (2020) found that cooperation and collaboration between management and employees prevail.

In conclusion, this study reiterates the call for ER stakeholders to collaborate when engaging on labour issues. The contributions of this study are a unionism strategy to theory and practice. Theoretically, this article expands further the body of knowledge on an effective union strategy. Practically, the contribution is a proposed strategic framework whereby union leaders collaborate with HR and ER managers to effectively negotiate agreements with management using government strategies and the ILO conventions. The study limitations are that generalisability is limited as it applies specifically to the SA ICT sector. In addition, the literature review as the data source abstract of this manuscript was limited to secondary data. Theoretical and empirical research is recommended for further research to explore the effectiveness of labour unionism in the ICT sectors of other African countries and globally.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors have not declared any conflicts of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Addison JT (2016). Collective bargaining systems and macroeconomic and microeconomic flexibility: The quest for appropriate institutional forms in advanced economies. IZA Journal of Labor Policy 5:19. |

|

|

Adolph C, Quince V, Prakash A (2017). The Shanghai effect: Do exports to China affect labour practices in Africa? World Development 89:1-18. |

|

|

Arslanov KM, Safin RR (2016). About the perspectives of legal regulation of labor relations. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues 19(SI):31-36. |

|

|

Asongu SA, Nwachukwu JC (2016). A brief future of time in the monopoly of scientific knowledge. Comparative Economic Studies 58(4):638-671. |

|

|

Asongu SA, Nwachukwu JC (2018). Educational quality thresholds in the diffusion of knowledge with mobile phones for inclusive human development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 129:164-172. |

|

|

Bach S, Bordogna L (2016). Public service management and employment relations in Europe: Emerging from the crisis. New York and London: Routledge. |

|

|

Bagi? D (2019). Croatia: Stability amidst heterogeneous collective bargaining patterns. In: Müller T, Vandaele TK, Waddington J (eds.), Collective Bargaining in Europe: Towards an endgame pp. 93-108. |

|

|

Balsmeier B (2017). Unions, collective relations laws and R&D in emerging and developing countries. Research Policy 46(1):292-304. |

|

|

Bernards N (2017). The International Labour Organization and African trade unions: tripartite fantasies and enduring struggles. Review of African Political Economy 44(153):399-414. |

|

|

Bhorat H, Cassim A, Yu D (2016). Temporary employment services in South Africa: Assessing the industry's economic contribution (LMIP Report 28). Pretoria: Labour Market Intelligence Partnership. |

|

|

Bisseker C (2017). On the brink: SA's political and fiscal cliff-hanger. Cape Town: Kwela. |

|

|

Bray M, Budd JW, Macneil J (2020). The many meanings of co-operation in the employment relationship and their implications. British Journal of Industrial Relations 58(1):114-141. |

|

|

Bray M, Macneil J, Stewart A (2017). Cooperation at work: How tribunals can help transform workplaces. Sydney: Federation Press. |

|

|

Brown GW, Mclean I, McMillan A (2018). Industrial relations: In a concise Oxford dictionary of politics and international relations. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

|

|

Budd JW, Bhave DP (2019). The employment relationship: Key elements, alternative frames of reference, and implications for HRM. In: Wilkinson A (ed.), Sage Handbook of Human Resource Management. Los Angeles: Sage, pp. 41-64. |

|

|

Caraway T, Ford M (2020). Labor and politics in Indonesia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

|

|

Cassim A, Casale D (2018). How large is the wage penalty in the labour broker sector? Evidence for South African using administrative data, UNU-WIDER Working Paper 2018/48, Helsinki: UNU-WIDER. |

|

|

Chun HM, Shin SY (2018). The Impact of Labor Union Influence on Corporate Social Responsibility. Sustainability 10(6):1922. |

|

|

Coetzee M, Schreuder D (2016). Personnel Psychology: An Applied Perspective. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. |

|

|

Colombo S, Regalia I (2016). Changing joint regulation and labour market policy in Italy during the crisis: On the edge of a paradigm shift? European Journal of Industrial Relations 22(3):295-309. |

|

|

Cook H, Mchenzie R, Forde C (2020). Union partnership as a facilitator to HRM: Improving implementation through oppositional engagement. International Journal of Human Resource Management 31(10):1262-1284. |

|

|

Cooke FL, Wang D, Wang J (2018). State capitalism in construction: Staffing practices and labor relations in Chinese construction firms in Africa. Journal of Industrial Relations 60(1):77-100. |

|

|

Currie D, Gormley T, Roche B, Teague P (2017). The management of workplace conflict: Contrasting pathways in the HRM literature. International Journal of Management Review 19(4):492-509. |

|

|

Debono M (2017). Attitudes towards trade unions in Malta. Economic and Industrial Democracy 1-21. Available at: |

|

|

Dromey J (2018). Power to the people: How stronger unions can deliver economic justice. UK: Institute for Public Policy Research. |

|

|

Ellem B, Goods C, Todd P (2020). Rethinking power, strategy and renewal: Members and unions in crisis. British Journal of Industrial Relations 58(2):424-446. |

|

|

Fanelli S, Salvatore FP, De Pascale G, Faccilongo N (2020). Insights for the future of health system partnerships in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic literature review. BMC Health Services Research 20(1):1-13. |

|

|

Goslinga S (2017). Job security, union participation and the need for (new) union services: Job security, union involvement and union activism. London: Routledge, pp. 81-96. |

|

|

Gough D, Oliver S, Thomas J (2017). Introducing systematic reviews. In Gough D, Olivier S, Thomas J (eds.), An introduction to systematic reviews (2nd ed.). London: Sage. pp. 1-18. |

|

|

Høgedahl L, Kongshøj K (2017). New trajectories of unionization in the Nordic Ghent countries: Changing labor market and welfare institutions, European Journal of Industrial Relations 23(4):365-380. |

|

|

Huws U, Spencer N, Syrdal D, Holts K (2017). Work in the European gig economy: Research results from the UK, Sweden, Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Italy. Brussels: Foundation for European Progressive Studies. |

|

|

International Labour Organisation (ILO) (2016). Facing the growing unemployment challenges in Africa: Press Release. Available at: |

|

|

International Labour Organisation (ILO) (2018). Report VI social dialogue and tripartism (International Labour Conference 107th Session). Geneva: ILO. |

|

|

International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) (2017). The 2017 ITUC global rights index: The world's worst countries for workers. Brussels: ITUC. |

|

|

International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) (2018). ITUC Global Rights Index 2018: Violations of workers rights. Available at: |

|

|

Isaac J (2018). Why are Australian wages lagging and what can be done about it? The Australian Economic Review 51(2):175-190. |

|

|

Kjellberg A (2020). Den svenska modellen i en oviss tid: Fack, arbetsgivare och kollektivavtal på en föränderlig arbetsmarknad. [The Swedish Model in an Uncertain Time: Trade Unions, Employers and Collective Agreements in a Changing Labor Market]. Arena Idé. |

|

|

Klindt MP (2017). Trade union renewal through local partnerships for skill formation. Transfer 23(4):441-455. |

|

|

Lulle A, Ungure E (2019). Latvia: Post-Soviet legacy and the impact of neoliberal ideology on collective bargaining. In Müller T, Vandaele K, Waddington J (eds.), Collective Bargaining in Europe: Towards an endgame. Brussels: ETUI. pp. 361-379. |

|

|

Madonsela S (2018). Critical reflections on state capture in South Africa. Insight on Africa 11(1):113-130. |

|

|

Martin E, Nolte I, Vitolo E (2016). The four Cs of disaster partnering: communication, cooperation, coordination, and collaboration. Disasters 40(4):621-643. |

|

|

Mncwango B (2016). Public Attitudes to Work in South Africa (LMIP Report 16). Pretoria: Labour Market Intelligence Partnership. Available at: |

|

|

Nel PS, Kirsten M, Swanepoel BJ, Erasmus B, Jordan B (2016). South African employment relations: Theory and Practice. Pretoria. Van Schalk. |

|

|

Njoku D (2017). Industrial relations. In: Njoku D (ed), Human Capital Management & Corporate Ethics: Theories and Practices. Owerri: Kriscona Publishers, pp. 114-134. |

|

|

Northrub JP (2018). Government intervention in industrial relations: Issues and problems. International Journal of Labour and Trade Unionism 3(4):16-29. |

|

|

Nyanga T, Tapfumanei CS (2019). Collective bargaining: A catalyst for dispute resolution between employers and employees in the retail industry in urban Mutare. Ushus Journal of Business Management 18(1):1-13. |

|

|

Obiekwe O, Felix O, Izim B (2018). Industrial relations environment in Nigeria: Implications for managers in Nigeria workplace. International Journal of Economics and Business Management 4(1):1-10. |

|

|

Okechukwu UF (2016). Trade unionism and wage agitations in Nigeria: The Nigerian Labour Congress. International Journal of Public Administration and Management Research 3(3):28-37. |

|

|

Orji MG, Kabiru JR (2017). Trade unionism on academic performance and development of Nigerian universities: A comparative study. Journal of World Economic Research 5(6):91-100. |

|

|

Prassl J (2018). Humans as a service: The promise and perils of work in the gig economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

|

|

Pratici L, Singer PM (2021). COVID-19 Vaccination: What Do We Expect for the Future? A Systematic Literature Review of Social Science Publications in the First Year of the Pandemic (2020-2021). Sustainability 13(15):8259. |

|

|

Ryall S, Blumenfeld S (2016). Unions and Union Membership in New Zealand-report on 2015 survey. Centre for Labour, Employment and Work (CLEW), Wellington, Victoria University of Wellington. |

|

|

Saad L (2018). Union support steady at 15-year high: Gallup. Available at: |

|

|

Schmalz S, Ludwig C, Webster E (2018). Power resources approach: Developments and challenges. Global Labour Journal 9(2):113-134. |

|

|

Schwab K (2017). The fourth industrial revolution. New York: Crown Business. |

|

|

Smith S (2016). Positive employment relations: An exploratory study (Unpublished Master's dissertation). North-West University, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa. |

|

|

Snyder H (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research 104:333-339. |

|

|

Statistics South Africa (StatsSA) (2019). Quarterly Labour Force Survey: 2nd Quarter. Statistical Report P0211. Pretoria. Statistics South Africa. |

|

|

Tapia M, Lee TL, Filipovitch M (2017). Supra-union and intersectional organizing: An examination of two prominent cases in the low-wage US restaurant industry. Journal of Industrial Relations 59(4):487-509. |

|

|

The European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC) (2018). What is social dialogue? Available at: |

|

|

Uys M, Holtzhausen M (2016). Factors that have an impact on the future trade unions in South Africa. Journal of Contemporary Management 13(1):1137-1184. |

|

|

Visser J (2016). Variation in Decentralisation-Articulation and Legal Structure. mimeo. |

|

|

Visser J (2019a). Trade union in the balance. International Labour Organisation: ACTRAV Working Paper. Geneva. |

|

|

Visser J (2019b). ICTWSS database: Version 6.0 Amsterdam. Amsterdam Institute for advanced labour studies: University of Amsterdam. Available at: |

|

|

Wilkinson A, Bacon N, Snell S, Lepak D (2019). Sage handbook of human resource management. London: Sage. |

|

|

Wood RC (2020). Perspectives on hospitality industry trade unionism in the UK and beyond. Research in Hospitality Management 10(2):137-147. |

|

|

Zlolniski C (2019). Coping with precarity: subsistence, labor, and community politics among farmworkers in northern Mexico. Dialectical Anthropology 43(1):77-92. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0