ABSTRACT

Experiential marketing is increasingly getting companies’ attention as a strategy to interact with consumers and engage them to better convey their brand image and positioning. However, its effects are still unclear both at the aggregate and individual levels. This paper addresses this topic and presents a field experiment investigating the effects of experiential marketing on brand image in retailing. Two similar consumer electronics stores with different strategies – traditional vs. experiential – constitute the setting in which a field experiment has been run. Two similar samples of consumers took part in our study by visiting one of these two stores, and answering a questionnaire before and after the visit with the primary goal to investigate the brand image and its changes due to the shopping visit. Brand image was measured as the overall brand attitude – via four items – and five specific desired brand claims that the company wanted to convey to consumers. Findings show that engaged consumers through the multisensory and interactive event arranged in the experiential store register higher levels of both brand attitude and all brand claims than those visiting the traditional store, and that the increase in both the dependent variables after the visit of the experiential store is higher than the increase in the traditional store. Thus, experiential stores are not only able to entertain consumers, but they are also able to educate them, by conveying them a set of brand claims more effectively than the traditional store.

Key words: Events, experiential marketing, field experiment, brand management, brand image, multisensoriality.

All over the world firms are devoting much of their budgets on experiential marketing in an effort to build strong, engaging and long-lasting relationships with their customer bases. According to the 2017 Freeman Global Brand Experience Study, almost 33% of Chief Marketing Officers expected to allocate between 21 and 50% of their budget to brand experience marketing over the next three to five years (Coffee and Monllos, 2017). Experiential marketing aims at attracting consumers’ attention where traditional communication is largely ignored by the demand: According to Agency EA as reported by Adweek (Coffee and Monllos, 2017) 89% of ad content is ignored by consumers stimulating firms to increase experiential spent at a double-digit rate in an effort to develop new appealing relationships. Engaging consumers in memorable experiences is the new challenge for firms in order to gain the competitive advantage they are looking for (Berry et al., 2002; Carbone and Haeckel, 1994; Haeckel et al., 2003; Lusch et al., 2007; Prahalad and Ramaswamy, 2003).

Despite the broad range of tangible and intangible elements that might constitute engaging customer experiences (Grewal et al., 2009; Zomerdijk and Voss, 2010), lively events appear as a key investment for experiential marketers. Traditionally regarded as residual in comparison to advertising, events now attract the interest of a growing number of companies, becoming as important as other elements of communication mix (Whiteling, 2005; Sneath et al., 2005). Many recent studies reveal that a large majority of marketers believe live events are critical to their company’s success, so that their budget is expected to increase in the next future (Agency EA, 2018; Bizzabo, 2017).

African countries are not an exception. The interest towards experiential marketing is evident in the long history of the African experiential marketing summit, which started in 2007, with a special attention to experiential events. The latters are growing fast, buy they are expected to grow even faster in the next future since there is a concrete need in the market according to experts as reported by The Guardian (Okere, 2015).

By enriching their offerings with emotional benefits companies aim at capturing consumers’ attention, enhancing their level of involvement, and developing long lasting relationships. Events represent the perfect context in which consumers can be immersed in highly sensorial and social environments (Rappaport, 2007). Engaging social events are powerful and useful experiential tools (Raghunathan and Corfman, 2006). Literature has long recognized the effect of experiential events in attracting new customers and increase brand image, by measuring several key aspects of customers’ reactions. Indeed, companies are mainly using events to drive lead generation and brand awareness, both in the B2B and B2C industries (Agency EA, 2018; Bizzabo, 2017). Other key metrics for measuring event value are new referrals and introductions, deal closure, value of sales, and upsell and cross-sell opportunities (CMO Council and E2MA, 2013).

However, in this paper, we propose to consider the educative value of events as an additional metric. Through carefully designing the whole experiential event consistently with the company’s goals and mission, organizations are able to transfer brand values and to convey adequate brand image (Drengner et al., 2008; Sneath et al., 2005). We propose that in order to capture such an effect, events should be assessed also by analyzing their contribution in changing participants’ perceptions about the brands. Thus, the emotional benefits of the basis of experiential events can also teach participants something about the brands.

The focus of this paper is primarily on experiential events and their effects on customers’ reactions. This research contributes to the literature by identifying a new measurement of events performances. The aim is to test the impact of experiential events on participants’ knowledge about the brand and its positioning. This will eventually enlarge the range of measures that organizations should adopt when assessing the return of their investments. Indeed, despite the widespread interest towards experiential events in stores, very little empirical work examines the real impact of this marketing tool (Drengner et al., 2008; Speed and Thompson, 2000; Sneath et al., 2005). Thus, there is an increasing need for assessing the effectiveness of the events (Martensen et al., 2007).

This research tests the differential effects of an experiential event organized in a store as opposed to traditional display on brand image. Specifically, the goal of our study is to address whether multisensory and interactive events are more or less effective in improving brand image than other traditional promotional tool, generally available and adopted by organizations. Our study compares responses of participants in the event to the responses of a different sample of consumers exposed to traditional display for the same products.

We decided to perform our analysis in a retail setting, which is a context where organizations can communicate their brand values and images in either a more traditional or experiential way. Our choice is due to two reasons. First, retailing constitutes the par excellence touch-point between organizations and their consumers, with the former trying to leverage on each touch-point to convey a consistent message, according to the Integrated Marketing Communication framework (Grove, Carlson and Dorsch, 2007). Toward this end, in store atmospheres can be managed to elicit specific consumers’ reactions, up to strongly engaging them (Bitner, 1992; Kotler, 1973; Donovan and Rossiter, 1982; Grewal et al., 2009). Second, in store atmosphere is very flexible and allows one to exploit both the functionalist and the hedonic and sensorial elements of positioning strategies (Schmitt, 1999, 2010; Lindstrom, 2006). Hence, the retailing context offers the opportunity to investigate two different marketing policies in a similar environment. The two stores were chosen because they are significantly similar in terms of positioning, target, location area, sales surface, store layout, yearly sales, number of salespeople, and products offered. Towards this end, the analysis has been run with the support of the retailer chain management.

The context that has been chosen for our experiment is home automation – otherwise known as domotics and smart home – as presented in the consumer electronics retail. This is due to three main reasons: first, domotics results from a process of converging industries, with many competitors coming from different sectors and no defined standards yet. Thus, consumers are required to deeply analyze the offerings before purchase any domotics products. Second, retailing is also a highly competitive industry, asking retailers to innovate continuously in an effort to identify new strategies to enrich their offerings and differentiate from digital players, who represent a serious threat. Third, domotics, being a complex product, requires both consumers and sale assistants to devote much attention in sharing knowledge during the selling. Indeed, making buyers understanding the value of this kind of products is a challenge for sale assistants that have to educate consumers first and then convince them to buy domotics products. Because of these three reasons, experiential marketing can offer interesting promises to create a better selling proposition and easier interactions on the point of sales.

Indeed, our findings demonstrate that the experiential event engaged consumers more than the traditional event. Specifically, both the dependent variables show a significant higher level in the multisensorial and experiential context compared to the traditional one.

Defining events

An event can be defined as a happening in which a product or corporate brand interacts face to face with an audience, typically formed by potential or actual customers. With the term event marketing, literature refers to both marketing of events and marketing with events (Cornwell and Maignan, 1998). While the former relates to events as a kind of product, needing specific marketing strategy and policies, such as the Olympic games, the latter is usually intended as a communication tool below the line, able to elicit personal interaction between products and consumers (Sneath et al., 2005), such as for instance the Red Bull Flugtag. Since we are interested in firms using events as part of their promotional strategy, in this paper focused on marketing with events. Indeed, event marketing can transmit extensive information on the product and the brand because thanks to the self-staging of the event by the company, the active participation of the target group members and their intense social interaction firms can communicate even detailed product information (Drengner et al., 2008).

Traditionally, organizations and scholars have paid attention to events as a driver of sponsorship. According to the last estimates by IEG (2018), more than $65 billion will be spent worldwide in 2018 on sponsorships, confirming a never-ending increase. By sponsoring an event, companies can reach specific targets and enrich the relationship with those consumers. Due to these benefits, great part of the little research conducted on events focuses on sponsoring activities (Close et al., 2006; Cornwell and Maignan, 1998; Gwinner and Eaton, 1999). Even if sponsorship can provide organizations with several and important benefits – such as higher brand awareness according to the prestige and dimension of the sponsee’s audience (Brown and Dacin, 1997; Close et al, 2006; Gardner and Schuman, 1987; Gross et al., 1987; Gwinner and Eaton, 1999; Meenaghan, 1991; Miyazaki and Morgan, 2001; Ruth and Simonin, 2003, 2006; Sneath et al., 2005) – self staged events are potentially more effective in creating and improving the brand image, given that their design is consistent with the desired brand image (Meyer and Schwager, 2007; Schmitt, 1999).

This trend has recently changed since companies have started to look at events as one of their own potential initiatives. The benefits of creating and organizing their own events – also called staged or proprietary events (Close et al., 2006) – instead of sponsoring someone else’s events, are raising the curiosity of an increasing number of organizations, which nowadays rely more upon brand and consumption experience management. According to Forrester Research (2016), on average 24% of the annual budget of Chief Marketing Officers is devoted to live events in order to connect with customers, educate attendees and generate new leads. Self-staged events make easier to actively include the target group in the communication process, thus favorably promoting the communicative impact. This is because the emotions elicited by the event influence the event image and this influences as well the image of the event object (Drengner et al., 2008), hence transferring the plethora of positive feelings on the image of the brand.

Interestingly, the attention gathered by events comes both from B2B and B2C markets, since meeting customers face-to-face emerges as a powerful opportunity for companies competing in any type of market. According to the 2006 Experiential Marketing Study conducted by Jack Morton, 80% of the responding consumers regard events as the medium with the richest informative content, while 68% consider the ability of a company to engage consumers personally relevant.

Designing engaging events is a strategy adopted to enrich the offer of retailers since although customers consistently search for products online, they also plan to purchase in-store (CMO Council and E2MA, 2013). Physical environments appear as a natural context in which firms can interact with consumers by creating engaging experiences. Indeed, marketing is rediscovering any opportunity to leverage on the five senses (Areni and Kim, 1993; Bone and Ellen, 1999; Crowley, 1993; d'Astous, 2000; Yalch and Spangenberg, 2000; Morrin and Rathneshwar, 2000; Milliman, 1982, 1986; Schmitt, 1999). At the beginning, this strategy has been adopted by retailers, who have enriched their offers with music, colors, fragrances, interactive tools, and special in-store events in which customers could taste particular products (Mehrabian and Russell, 1974; Nicholson, Clarke and Blakemore, 2002; Turley and Milliman, 2000). Nowadays, this type of promotion is spreading also to other businesses that have some direct point of contact with their customers, such as banks’ branches, museum and theaters (Chebat and Dubè, 2000; Joy and Sherry, 2003), as a way to interact with consumers and to get their attention (Close et al., 2006; Davenport and Beck, 2001). Especially for organizations devoid of places to interact with consumers, events emerge as powerful, flexible and “branded” points of contact with customers (Moore, 2003).

Consequently, engaging consumers and interacting with them seems fundamental: This is why more and more organizations pay attention to build rich, valid and memorable consumption experiences for their targets (Close et al., 2006; Morin et al., 2007). But do they positively affect brand image?

Effects of experiential events on brand image

Academic literature is devoting much attention to the evaluation of the effects of marketing events (Drengner et al., 2008). The existing studies assess the impact of events using a broad range of measures, resulting in an unclear framework of objectives and indicators (Abratt and Grobler, 1989; Javalgi et al., 1994; Crimmins and Horn, 1996; Javalgi et al., 1994; Sneath et al., 2005), but recent data reveal that companies are still far from getting advantages of them, by using them to achieve superficial goals. Despite traditional measures of performance related to experiential events, it was suggested that is important to understand how events contribute in creating and enhancing brand image, which is the real goal of experiential marketing strategies and campaigns.

Brand image can be defined as “perceptions about a brand as reflected in the brand associations held in memory” (Keller, 1993, p. 3). This concept lies at the basis of the whole marketing and it is the antecedent of any differentiation strategy (Close et al., 2006; Padgett and Allen, 1997). Choosing an appropriate brand image and creating an adequate correspondence between brand attributes and brand associations is a necessary requisite for success (Salciuviene et al., 2005).

During events, people are immersed in complex multisensory contexts, which by stimulating consumers’ senses increase their level of involvement and provide them with emotional holistic experiences (Langrehr, 1991; Rappaport, 2007; Schmitt, 1999, 2010). Traditional model of information processing posit that memory – measured as recall or recognition – is influenced by the manner in which information is encoded as well as the context in which information is retrieved. Hence, highly sensorial events are promising tools for companies because they are a favorable context in which brands can convey messages referring to the brand and its values easily and pleasantly. Through multisensory and interactive events, synesthesia is reached and consumers benefit from memorable consumption experiences. Indeed, experiential marketing, aiming at creating memorable consumption experiences, embeds the brand values in every feature, paying attention to generate a consistent communication flow (Meyer and Schwager, 2007). Through environmental stimuli, firms can elicit consumers’ emotions (Mehrabian and Russell, 1974; Turley and Milliman, 2000). Consequently, events represent the environmental contexts in which brands live: Hence, assessing their success means analyzing how consumers perceive brand image (Ruth and Simonin, 2003).

Even if previous studies have analyzed the contribution in changing brand image provided by both advertising and sponsorship with controversial results (Close et al., 2006; Cornwell et al., 2001; Dean, 1999; Gwinner and Eaton, 1999; Holbrook and Batra, 1987; Javalgi et al., 1994; Lardinoit and Quester, 2001), the one given by multisensory and interactive events is still unclear. According to experiential marketing literature, holistic experiences can be very effective in building brand image (Meyer and Schwager, 2007; Schmitt, 2010). Hence, it was proposed that interactive and multisensory events conveying holistic experiences, can contribute in enhancing brand image for those who take part in the event. Further, such an effect should appear also much more intense than traditional communication investments.

To investigate the effectiveness of multisensory and interactive in-store events, a field experiment was conducted. Indeed, experimental design is considered the best way to analyze the effectiveness of events (Cornwell and Maignan, 1998). Field experiments was opted for because they capture the essence of what happens during the event better than laboratory experiments, which cannot recreate the atmosphere of the events, which is instead a key driver of the experience. The current study benefits from the reality of the contexts in which the analyses are carried out, gaining in terms of external validity with reference to the findings (Harrison and List, 2004). The experiment refers to a well-known consumer electronics retail chain, headquartered in Europe. It operates in 21 countries. In Italy, the country in which the analysis has been run, it operates almost 300 stores. The big size of this company is greatly advantageous but at the same time makes standardization difficult. Thus, its stores provide several kinds of customer experiences with no homogeneity. Several stores of the chain adopt a very traditional layout and design, based on the traditional techniques of visual merchandising. In these stores domotics is traditionally presented, by displaying separately each product without transferring the synergies among products and among products categories. Indeed, category management principles help in displaying domotics products according to their utilitarian function, i.e. alarm system, lighting control system, heating, ventilation and air conditioning, and so forth. In these stores, traditionally, the selling approach strongly depends on the ability and knowledge of the sale assistants, who play a key role.

However, in an effort to go through new value propositions, in occasion of the launch of a new line of domotics products, the company recently adopted the experiential marketing principles to organize their own self-staged events. Thus, in one of their stores, they started to offer customers a multisensory and interactive event to recreate the benefits of the domotics according to the experiential view. Inside the store hosting the experiential event, a one-floor 100 square meters flat has been created. In the rooms of the flat, fully furnished and decorated, had all the domotics products to be promoted, installed and perfectly working, like in a real flat. Customers visiting the store during the event could enter the flat, touch everything inside, and try the functioning of all the products on their own. This event is highly sensorial, relying highly on interactive and tactile inputs. The latter have been recently explored in marketing literature, resulting as effective antecedents of consumers’ favorability towards products and stores. Tactile inputs are particular beneficial for high quality products with specific regard to those aspects that are best explored by touch (Grohmann et al., 2007), but also for products rich in informational content, which need an innovative communication approach (Rust and Oliver, 1994). Product trial offers consumers the opportunities to use all the five senses to interact with products, resulting in a positive affective response regardless of the product type (functional versus hedonic) and of the involvement level (Kim and Morris, 2007). Indeed, touch provides “an enjoyable hedonic experience for the consumer” even outside of the product touch context (Peck and Wiggins, 2006: 66). Such an experiential strategy is expected to make consumers completely understand the benefits of the smart home, without asking for the traditional explanation by installers or electricians or even the sale assistants.

Our study aims to test the impact of the experiential display on brand image, and compare the results with the one gained on traditional display. Thus, our field experiment is structured as a one-factor (traditional display vs. experiential display) between subjects design. Customers took part in the experiment according to a randomization criterion. Then, they were asked to participate in the study, and have been administered a questionnaire on site both before entering and after exiting one of the two stores: The one in which the event was staged (experiential display condition), and the one in which products were featured according to a traditional utilitarian display (traditional display condition). Data have been collected in both stores during a two-week period of time in which no holidays took place, on each day of the week, both in the morning and in the afternoon. No known seasonal aspects could bias the results.

Both the pre-visit and post-visit questionnaires collected measures for the dependent variable, brand image (measured by Brand Attitude and Brand Claim Recognition scales), and the pre-visit questionnaire contained also a set of socio-demographics variables and two further scales to gather the level of familiarity with consumer electronics stores and products. The list of variables included in the questionnaire are:

Part A: Pre-visit questionnaire

Familiarity variables:

1) Having previously visited a consumer electronics store

2) Having previously purchased a consumer electronics product

Dependent variables:

1) Brand attitude scale – 4 items

2) Brand Claim Recognition scale – 5 items:

3) The brand improves the home comfort thanks to the automatic mechanisms

4) The brand let you save on energy supply by mean of a clever use of resources

5) The brand make your home safer

6) The brand allows the effective communication within rooms

7) The brand allows people to control the home automatic mechanisms via web and cell phone

Demographic variables were:

1) Gender

2) Age

Part 2: Post-visit questionnaire

Dependent variables:

1) Brand attitude scale – 4 items

2) Brand Claim Recognition scale – 5 items:

3) The brand improves the home comfort thanks to the automatic mechanisms

4) The brand let you save on energy supply by mean of a clever use of resources

5) The brand make your home safer

6) The brand allows the effective communication within rooms

7) The brand allows people to control the home automatic mechanisms via web and cell phone

In total, 150 usable questionnaires were collected for the experiential condition and 150 questionnaires for the traditional display condition. Totally, 300 questionnaires were filled.

Brand attitude was measured via the attitude toward brand scale (Sengupta and Fitzsimons, 2004; Kirmani and Shiv, 1998). The scale proposes 4-items (“bad/good,” “not likeable/likeable,” and “unappealing/appealing”, “I do not/do like it”) and their mean has to be computed. Both for traditional and experiential display, and both for pre-visit and post-visit Cronbach’s alpha registered values higher than 0.9, so that it can be concluded that the scale is highly reliable. Table 1 reports the findings of the reliability analysis.

To measure brand claim recognition a set of items developed according to the specific marketing message that the company desired to convey via the event was used (Garretson and Burton, 2005). To identify the items to use in the brand claim recognition scale, previously interviewed management in charge of the event was used so that the goals in terms of brand positioning were made explicit. Thanks to these interviewees, five specific goals were identified: Organization aimed at making individuals understand the benefits of the domotics products – namely, the greater comfort, the energy saving, the safety improvement, the improvement in internal communication and the remote control.

Preliminary analysis

Before comparing the results of the two strategies of displaying domotics, it was checked whether the two groups are comparable with regard to the main known variables that can have a role in affecting our findings. The two groups – the one exposed to the traditional display and the one exposed to the experiential display – are pretty similar, with no significant difference regarding gender (56% and 59% of males respectively; χ2=.22; p=NS), age (approximately the average age is 36 years for both groups), nor previous buying behavior of electronic products (60 and 61% of previous purchase respectively; χ2=.06; p=NS); and visiting of electronic stores (67 and 64% of previous visit respectively (χ2=.37; p=NS). Table 2 reports the main results of the preliminary analysis.

The above findings allow us to go further in the data analysis to test the effects of the two displays without any potential impact of confounding variables.

Comparing the effects of experiential vs. traditional display on brand attitude

In order to compare the effects of traditional and experiential displays with regard to the two dimensions of brand image that have been included in the questionnaire, six repeated measure designs were built with brand attitude and the five measures of brand claim recognition as within-subject variables and the type of experience provided (traditional vs experiential display) as a between-subjects factor.

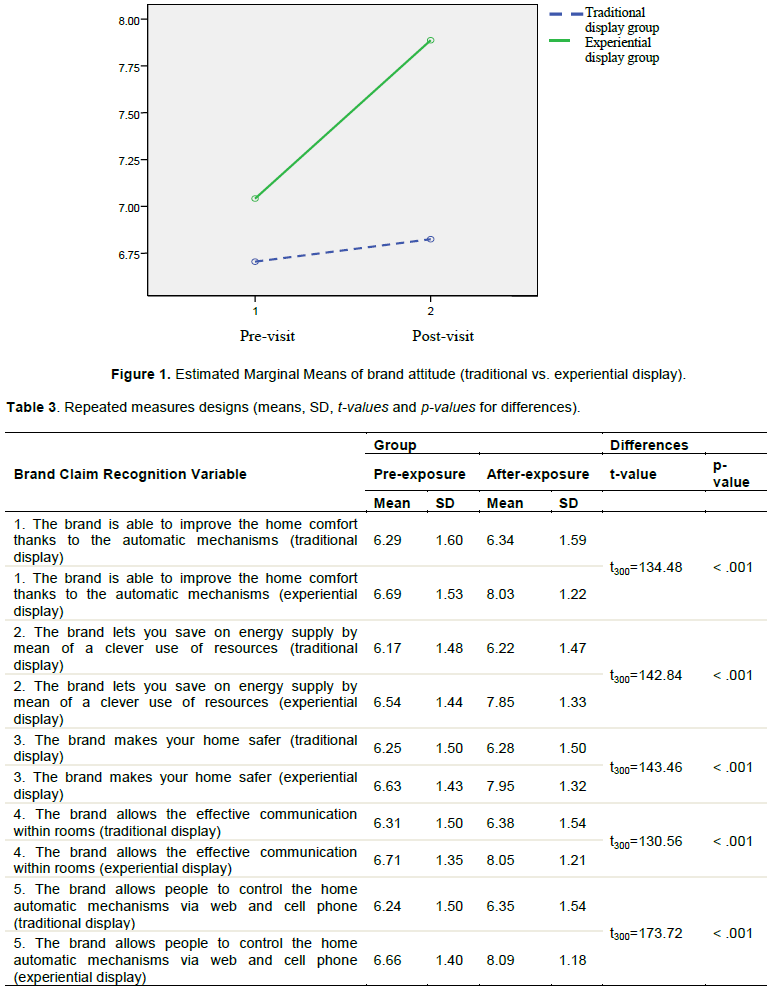

With regard to brand attitude, empirical findings reveal a significant main effect of the type of experience provided on attitude (F(1,298) = 115.12; p < .001), which shows a more positive brand attitude after exposure (MTraditionalDisplay = 6.82 and MExperientialDisplay = 7.89) than before exposure (MTraditionalDisplay = 6.70 and MExperientialDisplay = 7.04). Moreover, findings indicated that there is a significant interaction between the improvement of brand attitude experienced by participants and the type of experience in which they were involved (traditional vs. experiential display): F(1,298) = 64.97; p < .001. Thus, the effect of participation in the domotics event in the experiential display was significantly stronger in improving brand attitude than the exposure to the traditional visual merchandising. Figure 1 shows the plot of the estimated marginal means of brand attitude.

Comparing the effects of experiential vs. traditional display on brand claim recognition

Further, five repeated measure designs were done with the five measures of brand claim recognition (each separately) as within-subject variables and the type of experience provided (traditional vs. experiential display) as a between-subjects factor. Our empirical findings show that for each and every brand claim recognition item, the exposure to the display has a positive effect, and that is always stronger for those who have been exposed to the experiential display as compared to those who exposed to the traditional display of the same domotics products. More in details, findings show a significant main effect of the type of experience provided on the belief that the brand is able to improve the house comfort thanks to automatic mechanism (F(1,298) = 134.48; p < .001). Higher levels of brand claim recognition after exposure (MTraditionalDisplay = 6.34 and MExperientialDisplay = 8.03) than before exposure (MTraditionalDisplay = 6.29 and MExperientialDisplay = 6.69) was obtained. Moreover, findings indicate that there is a significant interaction between the enforcement of this idea and the type of situation participants experienced (traditional vs. experiential display): F(1,298) = 117.06; p < .001.

Similar findings emerge with regard to the other four items of brand claim recognition. Interestingly, for each brand claim recognition item, although also participants in the traditional condition reported higher levels of belief, such an increase was statistically significantly higher for participants in the experiential display condition. Statistical details are reported in Table 3, while the plots of the estimated marginal means for each of the five items composing the brand claim recognition are represented in Figure 2.

As shown in Table 3 and Figure 2, participating in the event organized in the experiential store is more effective in teaching consumers the domotics benefits – measured via the brand claim recognition items – than the traditional display. Results reveal a significant effect of the type of experience provided on the perception that the featured brand allows people to save energy (F(1, 298) = 142.84, p < =.001). Again, a higher level of this item of brand claim recognition after visit (MTraditionalDisplay = 6.22 and MExperientialDisplay = 7.85) than before visit (MTraditionalDisplay = 6.17 and MExperientialDisplay = 6.54) wasobtained. Findings show that there is a significant interaction between the enforcement of this perception and the type of experience provided, with the former being stronger in the event condition: F(1, 298) = 123.82; p < .001. Similar results for the other items of brand claim recognition were obtained. Participants enforce their opinion about the fact that the brand makes their home safer (before the visit: MTraditionalDisplay = 6.25 and MExperientialDisplay = 6.63; after the visit: MTraditionalDisplay = 6.28 and MExperientialDisplay = 7.95; F(1, 298) = 143.46, p < .001); that it allows the effective communication within rooms (before the visit: MTraditionalDisplay = 6.31 and MExperientialDiplay = 6.71; after the visit: MTraditionalDisplay = 6.38 and MExperientialDisplay = 8.05; F(1, 298) = 130.56; p < .001) and that it allows people to control the home automatic mechanisms via web and cell phone (before the visit: MTraditionalDisplay = 6.24 and MExperientialDisplay = 6.66; after the visit: MTraditionalDisplay = 6.35 and MExperientialDisplay = 8.09; F(1,298) = 173.72; p < .001). In all the cases, findings show that there are significant interactions between the enforcement of the association of these claims with the featured brand and the type of experience provided: respectively, F(1, 298) = 132.32; p < .001; F(1, 298) = 130.55; p < .001; F(1,298) = 128.92, p < .001.

Do the way in which products are presented affect consumers’ perception of the brand? Our experimental study addresses this topic and it offers a positive answer to this question in four different meanings.

First, participating in a multisensory and interactive event in a store with offering an experiential display aiming at the creation of a unique experience improves the brand image. This result appears with both regard to Brand Attitude and the five items used to measure Brand Claim Recognition. Any of the investigated variables increases in a significant way after the participation in the event.

Second, traditional display has a positive impact on all the dimensions of brand image. Thus, our findings confirm the effectiveness of the traditional principles and practices about product category, training of sale assistants, and so on.

However – and that is our third finding – such an effect is weaker than the one produced by multisensory and interactive events in retailing. Through field study, the extent to which multisensory and interactive events hosted in a retailing setting raise participants’ brand image better than a traditional display was examined. It was found that multisensory events hosted in stores with experiential display are more effective both with regard to brand attitude and brand claim recognition. Indeed, as predicted, our study confirms that when people are exposed to events based on a holistic experience their overall brand attitude increases more than when they are exposed to a traditional display, leading to brand attitude values close to 8 points out of 9. A significant interaction effect exists between the type of experience provided (traditional vs. experiential display) and brand attitude. In addition, the present study confirms that the multisensory and interactive event is able to convey to participants accurate information on the brand, showing its ability to spread the values that the organization wants to transfer to participants. Findings indicate that multisensory and interactive events help more than traditional display in enhancing the perception that the brand allows for comfort, energy saving, safety, effective communication and easy remote control. With regard to the whole set of Brand Claim Recognition Scales, exposure to the multisensory and interactive event leads to an increase between 1.29 and 1.43 points; while exposure to the traditional display leads to an increase between .03 and .11 points. Interestingly, these results emerge even given the high value of each variable prior to the exposure: In both cases, the level of these variables before the exposure is higher than 6 points, and all of them increase after the treatment.

Finally, the significant positive impact of the experience provided in a store on both brand attitude and brand claim recognition is particularly interesting for experiential marketing literature. Indeed, experiential marketing is largely recognized as a powerful driver of intense and engaging customer relationships. Especially service organizations invest to craft the customer experience to offer highly differentiated and unique “experience-centric services” (Voss, Roth, and Chase, 2008). From the customers’ perspective, experience-centric services offer emotional connections, made possible by a careful experience design of myriad elements as for any services cape (Bitner, 1992; Grove and Fisk, 1997). Thanks to tangible and intangible service elements in the service-delivery system, organizations develop their experience-centric services (Grewal, Levy and Kumar, 2009; Zomerdijk and Voss, 2010), emotionally engaging their customers (Sorescu et al., 2011).

As a consequence, an increase of brand attitude is commonly regarded as a key result of any investment in experiential marketing. Our findings on brand attitude confirm such a general belief. However, to the best of our knowledge, a similar impact of experiential marketing on specific brand beliefs has never been tested: Experiential marketing is effective not only to increase the general consumers’ attitude toward the brand, but also to transfer consumers some key messages about the brand. Experiential marketing value is twofold: It is able to entertain and to teach consumers. Multisensory and interactive events emerge as an effective powerful communication tool to convey brand claims and improve brand attitude, even for transferring values far from the perceived brand positioning.

The primary goal of this manuscript is to explore how multisensory and interactive events contribute in building brand positioning (Close et al., 2006; Morin et al., 2007; Sneath et al., 2005). Although events are increasingly considered as a powerful communication tool to engage consumers and to enhance their attitude toward the brand, the differential effect of these tools in comparison to other marketing strategies is yet not well defined. Literature, in fact, does not define a clear framework for measuring directly the influence of events neither to compare them. This gap needs to be filled, especially nowadays, with a large number of organizations investing in multisensory and holistic experiences in order to differentiate themselves from the rest of the market and to develop strong, engaging and long-lasting relationships with their customers. Key experiential cases include the project Healthy imagination by General Electric proposed to 700 industry professionals and based on storytelling by doctors operating also in a rural African clinic, and the recent investment by Nivea in Cape Town named NIVEA SunSlide, a giant inflatable slip ‘n slide for entertaining kids and educating their parents about sunscreen creams.

Toward the aforementioned end of our study, the study was aimed at exploring the relationship between multisensoryand interactive events and brand image. In particular, the study focuses on measuring and evaluating the real impact that this type of events can provide to companies’ brand image. Specifically, thanks to a field experiment, the contribution that events provide to enhancing brand image was investigated, and comparison of this contribution with the one offered by traditional display in a retail setting was made.

Multisensory and interactive events improve participants’ brand attitude and they also convey the particular messages the company wants to deliver. These findings are in line with the theoretical framework that deems multisensory and interactive events as a powerful tool for companies that want to communicate and relay brand values by positively rising brand image (Ruth and Simonin, 2003). They also extend the perspective undertaken by Close et al. (2006) that considers mainly sponsorship as a valuable tool to increase brand image.

Moreover, the multisensory and interactive event appeals to consumers better than traditional display; it allows for a deeper understanding of the ideas and the messages that the organization want to deliver. This findings support the theoretical approach that underlines the importance, for a company that does not have its own retail environment, of performing multisensory and interactive events to create direct touch-points with customers.

This study also provides some guidelines for managers that want to exploit the opportunities offered by multisensory and interactive events. Despite the importance of this tool within companies’ marketing mix, managers are not provided with a clear understanding of what multisensory and interactive events can really help to achieve. Toward this goal, this work clearly shows that multisensory and interactive events contribute to enhance brand image. Multisensory and interactive events engage consumers, leading to more positive associations with the brands. Further, our study provides highlights that justify and support the use of multisensory and interactive events in specific settings rather than traditional display. Finally, it helps managers to evaluate concretely the contribution that multisensory and interactive events provide to the organizations and particularly to the brand, by showing how to measure their impacts.

However, in order to measure the success of this marketing tool, organizations must (1) firstly define their goals clearly, and, (2) design the events accordingly. Those are two relevant preliminary steps of their marketing process.

Interestingly, multisensory and interactive events are powerful even for brands which are already perceived favorably by consumers, and even for situations in which the messages the organization aims at transferring are far from the actual brand positioning. In these cases consumers’ multisensory stimulation strongly facilitates the transfer of brand image benefits.

This study, like most, suffers from some limitations. First, the specific analyzed multisensory and interactive events might not be representative of all the kinds of happenings that companies can organize. In future researches, it would be necessary to take into consideration this element and try to extend these findings to other type of multisensory and interactive events. Another potential limiting factor is the specific setting where the field experiment took place, the retailing environment. While we were interested in comparing the contribution of this multisensory and interactive event with a traditional display, this might limit the generalizability of the study. Comparing the effectiveness of multisensory and interactive events with sponsorships would be of particular interest for organizations evaluating the relative benefits of these two marketing options. In future research, this should be an element to take care of. Further, estimating the contribution that hosting a company’s multisensory and interactive events might have for the housing company (i.e. the retailer) and evaluating the aspect for which they are convenient for both firms could be of interest for organizations willing to adopt co-marketing strategies. Finally, identifying the antecedents of the success of events, such as their level of multisensory stimulation and of interaction, is as a relevant topic for future research.

Apart from these weaknesses, our study benefits from a real event, providing a more realistic context than the one generally used in laboratory experiments. Specifically, the aim of this event was twofold: (1) to improve the brand attitude among the final consumers; and (2) to teach consumers the key benefits offered by a highly complex product category such as domotics. Our study reveals that experiential marketing can help companies to achieve both goals, so that entertainment goes hand by hand with education. The two kind of befits provided by experiential marketing generate higher level of brand image than only leveraging on educative investments. Customers can learn brand benefits in many different ways, including having sale assistants explaining them and processing visual merchandising indications. But when education meets entertainment customers learn better. Are companies ready to teach while entertaining? Future case studies will provide us with the answer.

The authors gratefully acknowledge support by SDA Bocconi School of Management, the kind collaboration provided by the managers of the companies involved, and prof. Isabella Soscia and Dr. Irene Scopelliti for their valuable comments on previous versions. Order of authorship is arbitrary; all authors contributed equally to this research.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Abratt R, Grobler PS (1989). The evaluation of sports sponsorships. International Journal of Advertising 8(4):351-362.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Agency EA (2018). 2018 Experiential Marketing Trend Report. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Areni CS, Kim D (1993). The influence of background music on shopping behavior: classical versus top-forty music in a wine store. ACR North American Advances. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Berry LL, Carbone LP, Haeckel SH (2002). Managing the total customer experience. MIT Sloan Management Review 43(3):85-89.

|

|

|

|

|

Bitner MJ (1992). Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. The Journal of Marketing 56(2):57-71.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bizzabo (2017). Event marketing 2018: Benchmarks and trends. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Brown TJ, Dacin PA (1997). The Company and the Product: Corporate Associations and Consumer Product Responses. Journal of Marketing 61(1):68-84.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Carbone LP, Haeckel SH (1994) Engineering customer experiences. Marketing Management 3(3):8-19.

|

|

|

|

|

Chebat JC, Dubé L (2000). Evolution and Challenges Facing Retail Atmospherics:: The Apprentice Sorcerer Is Dying. Journal of Business Research 49(2):89-90.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Close AG, Finney RZ, Lacey RZ, Sneath JZ (2006). Engaging the consumer through event marketing: Linking attendees with the sponsor, community, and brand. Journal of Advertising Research 46(4):420-433.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

CMO Council & E2MA (2013). Customer attainment from event engagement. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Coffee P, Monllos K (2017). Are you experiential? Adweek 48(27):18-21. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Cornwell TB, Maignan I (1998). An international review of sponsorship research. Journal of Advertising 27(1):1-21.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cornwell TB, Roy DP, Steinard EA (2001). Exploring managers' perceptions of the impact of sponsorship on brand equity. Journal of Advertising 30(2):41-51.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Crimmins J, Horn M (1996). Sponsorship: From management ego trip to marketing success. Journal of Advertising Research 36(4):11-21.

|

|

|

|

|

Crowley AE (1993). The two-dimensional impact of color on shopping. Marketing Letters 4(1):59-69.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

D'Astous A (2000). Irritating aspects of the shopping environment. Journal of Business Research 49(2):149-156.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Davenport TH, Beck JC (2001). The attention economy: Understanding the new currency of business. Harvard Business Press. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Dean DH (1999). Brand endorsement, popularity, and event sponsorship as advertising cues affecting consumer pre-purchase attitudes. Journal of Advertising 28(3):1-12.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Donovan RJ, Rossiter JR (1982). Store atmosphere: an environmental psychology approach. Journal of Retailing 58(1):34-57.

|

|

|

|

|

Drengner J, Gaus H, Jahn S (2008). Does flow influence the brand image in event marketing?. Journal of Advertising Research 48(1):138-147.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bone PF, Ellen PS (1999). Scents in the marketplace: Explaining a fraction of olfaction. Journal of Retailing 75(2):243-262.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Forrester Research (2016). 2016 B2B budget plans show that it's time for a digital wake-up call. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Gardner PM, Shuman PJ (1987). Sponsorship: An important component of the promotions mix. Journal of Advertising 16(1):11-17.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Garretson JA, Burton S (2005). The role of spokescharacters as advertisement and package cues in integrated marketing communications. Journal of Marketing 69(4):118-132.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Grewal D, Levy M, Kumar V (2009). Customer experience management in retailing: An organizing framework. Journal of Retailing 85(1):1-14.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Grohmann B, Spangenberg ER, Sprott DE (2007). The influence of tactile input on the evaluation of retail product offerings. Journal of Retailing 83(2):237-245.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gross AC, Traylor MB, Shuman PJ (1987). Corporate sponsorship of art and sports events in North America. In Esomar Congress. pp. 9-13.

|

|

|

|

|

Grove SJ, Carlson L, Dorsch MJ (2007). Comparing the Application of Integrated Marketing Communication (IMC) in Magazine Ads Across Product Type and Time. Journal of Advertising 36(1):37–54.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Grove SJ, Fisk RP (1997). The impact of other customers on service experiences: A critical incident examination of "getting along." Journal of Retailing 73(1):63-85.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gwinner KP, Eaton J (1999). Building brand image through event sponsorship: The role of image transfer. Journal of Advertising 28(4):47–57.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Haeckel SH, Carbone LP, Berry LL (2003). How to lead the customer experience. Marketing Management 12(1):18-18.

|

|

|

|

|

Harrison GW, List JA (2004). Field experiments. Journal of Economic Literature 42(4):1009-1055.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Holbrook MB, Batra R (1987). Assessing the role of emotions as mediators of consumer responses to advertising. Journal of Consumer Research 14(3):404-420.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

IEG (2018). What sponsors want and were dollars will go in 2018. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Javalgi RG, Traylor MB, Gross AC, Lampman E (1994). Awareness of sponsorship and corporate image: An empirical investigation. Journal of Advertising 23(4):47-58.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Joy A, Sherry Jr JF (2003). Speaking of art as embodied imagination: A multisensory approach to understanding aesthetic experience. Journal of Consumer Research 30(2):259-282.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Keller KL (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. The Journal of Marketing 57(1):1-22.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kim J, Morris J (2007). The power of affective response and cognitive structure in product-trial attitude formation. Journal of Advertising 36(1):95-106.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kirmani A, Shiv B (1998). Effects of source congruity on brand attitudes and beliefs: The moderating role of issue-relevant elaboration. Journal of Consumer Psychology 7(1):25-47.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kotler P (1973). Atmospherics as a marketing tool. Journal of Retailing 49(4):48-64.

|

|

|

|

|

Langrehr FW (1991). Retail shopping mall semiotics and hedonic consumption. ACR North American Advances. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Lardinoit T, Quester PG (2001). Attitudinal effects of combined sponsorship and sponsor's prominence on basketball in Europe. Journal of Advertising Research 41(1):48–58.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lindstrom M (2006). Brand sense: How to build powerful brands through touch, taste, smell, sight and sound. Strategic Direction 22(2):1-10.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lusch RF, Vargo SL, O'Brien M (2007). Competing through service: Insights from service-dominant logic. Journal of Retailing 83(1):5-18.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Martensen A, Grønholdt L, Bendtsen L, Jensen MJ (2007). Application of a model for the effectiveness of event marketing. Journal of Advertising Research 47(3):283-299.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

McDonald C (1991). Sponsorship and the Image of the Sponsor. European Journal of Marketing, 25(11), 31–38. Available at:

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Meenaghan T (1991). Sponsorship – Legitimising the Medium. European Journal of Marketing 25(11):5-10.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mehrabian A, Russell JA (1974). An approach to environmental psychology, Cambridge: MIT Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Meyer C, Schwager A (2007). Customer experience. Harvard Business Review 85(2):116-126.

|

|

|

|

|

Milliman RE (1982). Using Background Music to Affect the Behavior of Supermarket Shoppers. Journal of Marketing 46(3):86.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Milliman RE (1986). The Influence of Background Music on the Behavior of Restaurant Patrons. Journal of Consumer Research 13(2):286.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Miyazaki AD, Morgan AG (2001). Assessing market value of event sponsoring: Corporate olympic sponsorships. Journal of Advertising Research 41(1):1-9.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Moore RE (2003). From genericide to viral marketing: On "brand." Language and Communication 23(3-4):331-357.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Morin S, Dubé L, Chebat JC (2007). The role of pleasant music in servicescapes: A test of the dual model of environmental perception. Journal of Retailing 83(1):115-130.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Morrin M, Ratneshwar S (2000). The impact of ambient scent on evaluation, attention, and memory for familiar and unfamiliar brands. Journal of Business Research 49(2):157-165.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Nicholson M, Clarke I, Blakemore M (2002). One brand, three ways to shop': Situational variables and multichannel consumer behaviour. International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 12(2):131-148.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Okere R (2015). Imperatives of experiential marketing in West Africa, by experts- Business- The Guardian Nigeria Newspaper – Nigeria and World News. Retrieved September 18, 2018. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Padgett D, Allen D (1997). Communicating experiences: A narrative approach to creating service brand image. Journal of Advertising 26(4):49-62.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Peck J, Wiggins J (2006). It Just Feels Good: Customers' Affective Response to Touch and Its Influence on Persuasion. Journal of Marketing 70(4):56-69.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Prahalad CK, Ramaswamy V (2003). The new frontier of experience innovation. MIT Sloan Management Review 44(4):12.

|

|

|

|

|

Raghunathan R, Corfman K (2006). Is Happiness Shared Doubled and Sadness Shared Halved? Social Influence on Enjoyment of Hedonic Experiences. Journal of Marketing Research 43(3):386-394.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Rappaport SD (2007). Lessons from online practice: New advertising models. Journal of Advertising Research 47(2):135-141.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Rust RT, Oliver RW (1994). Notes and comments: The death of advertising. Journal of Advertising 23(4):71-77.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ruth JA, Simonin BL (2003). Brought to you by Brand A and Brand B" Investigating Multiple Sponsors' Influence on Consumers' Attitudes Toward Sponsored Events. Journal of Advertising 32(3):19-30.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ruth JA, Simonin BL (2006). The Power Of Numbers: Investigating the Impact of Event Roster Size in Consumer Response to Sponsorship. Journal of Advertising 35(4):7-20.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Salciuviene L, Auruskeviciene V, Virvilaite R (2005). Assessing brand image dimensionality in a cross-cultural context. In Papadopoulos N, Veloutsou C (Eds.), Marketing from the Trenches: Perspectives on the Road Ahead, Athens, Greece: Athens Institute of International European Research pp. 223-234.

|

|

|

|

|

Schmitt B (1999). Experiential marketing. How to get customers to SENSE, FEEL, THINK, ACT and RELATE to your company brands. New York: The Free Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Schmitt B (2010). Customer experience management: A revolutionary approach to connecting with your customers. John Wiley & Sons.

|

|

|

|

|

Sengupta J, Fitzsimons GJ (2004). The Effect of Analyzing Reasons on the Stability of Brand Attitudes: A Reconciliation of Opposing Predictions. Journal of Consumer Research 31(3):705-711.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sneath JZ, Finney RZ, Close AG (2005). An IMC approach to event marketing: The effects of sponsorship and experience on customer attitudes. Journal of Advertising Research 45(4):373-381.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sorescu A, Frambach RT, Singh J, Rangaswamy A, Bridges C (2011). Innovations in retail business models. Journal of Retailing 87:S3-S16.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Speed R, Thompson P (2000). Determinants of sports sponsorship response. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 28(2):226-238.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Turley LW, Milliman RE (2000). Atmospheric effects on shopping behavior: A review of the experimental evidence. Journal of Business Research 49(2):193-211.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Voss C, Roth AV, Chase RB (2008). Experience, service operations strategy, and services as destinations: Foundations and exploratory investigation. Production and Operations Management 17(3):247-266.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Whiteling I (2005). Global meeting strategies. Business Week, October 24.

|

|

|

|

|

Yalch RF, Spangenberg ER (2000). The effects of music in a retail setting on real and perceived shopping times. Journal of Business Research 49(2):139-147.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Zomerdijk LG, Voss CA (2010). Service design for experience-centric services. Journal of Service Research 13(1):67-82.

Crossref

|

|