ABSTRACT

This study attempts to enlarge knowledge on public value co-creation within a complex environment such as artification. The transfiguration of object that is not regarded as art in the traditional sense into something art-like underpins the development of processes suitable for analyses within the co-creation framework. The case of “EXIT”, the photographic exhibition on Ghost hotel in the province of Pavia (Lombardy, Northern Italy) has been carried out in order to achieve the research aim. The results, came out from the content analysis, demonstrated how artification triggers public value co-creation under specific conditions like the implementation of managerial logics, tools, and model. The conceptual model of artification co-creation attempts to fulfil the literature gaps which call for more investigations on the degree of citizen engagement in relation to the outcome of value creation within the democratic sphere.

Key words: Artification, value, co-creation, multi-actors engagement, strategic triangle, outcome, content analysis.

The famous quotation "Beauty will save the world" from Dostoevsky (2010) well-known novel "The Idiot", reveals its effectiveness in relation to the evolution of art, its meaning and the social values ​​transmitted in the contemporary age (Miller, 1981). The challenge trigged by the cultural sector is to change something that is not art in art-like (artification) as perceived by the audience. This concept, introduced by Finnish scholars of Contemporary Aesthetics in 2005, has been broaden investigating at multi-disciplinary levels. According to the Shapiro’s model (2019), the processes of artification engage many actors, resources and activities whose relationships open up new strands of research within the managerial studies. With regard to the latter, service science calls for more investigations on complex environment, where the value is co-created by the interactions of multi-actors (Pinho et al., 2014; Petrescu, 2019). Contextually, public management studies highlight, among critical issues on co-creation that are still under-investigated, the engagement of citizens as co-designers or co-implementers as well as the outcome of co-creation within the democratic sphere (Voorberg et al., 2015; Best et al., 2019). Moreover, the multi-actor theory of public value co-creation addresses research to provide more evidence on the accuracy and the effectiveness of the updated “Strategic Triangle” framework within complex environment (Bryson et al., 2017).

Considering these literature gaps, this pioneering study attempts to explore the public value co-creation in the field of artification. Thus, the research aims at extending knowledge under both managerial and cultural heritage perspectives.

Value co-creation framework

The study of value creation has been developing under different managerial perspectives within service system (Vargo and Lusch, 2004) as well as public administration literatures (Moore, 1995). Both strands of research have contributed to extend the understanding of this phenomenon with strategic implications for the market and the state. Their common point is the notion of value acknowledged as: “a complex and broad-based assessment of an object or set of objects […] characterized by both cognitive and emotive elements, arrived at after some deliberation, and because a value is part of the individual’s definition of self, it is not easily changed, and it has the potential to elicit action” (Bozeman, 2007: 13). This concept of value is closely linked to the cognitive but, also, emotional elements of those who produce and those who perceive that value (Hodgkinson et al., 2017; Ng and Vargo, 2018). The creation of value is, in fact, intimately linked to personal factors such as self-fulfilment, for having influenced the creation of that value, especially if it is provided for the benefit of the community (Bovaird et al., 2015; Alonso et al., 2019). Moreover, the adjective “private” or “public” ascribed to value concerns the same object. According to Alford and Hughes (2008), private value stands for value consumed individually by users, while public value is received collectively by the citizens, based on the needs and wants of them (Edvardsson et al., 2011). With particular regard to private value creation, the research focused on the relationship between consumer and provider has introduced the notion of value in use as alternative to that of value in exchange. The latter, according to the Good-Dominant logic, is created by the provider and exchanged in the marketplace for money. Conversely, the ‘value in use’ is “based on user’s perceptions and is created throughout and from the collaboration and interaction between the consumer and the provider in mutual exchanges, during use, consumption or experience” (Petrescu, 2019: 1734). According to the latter, providers and consumers do not have distinct roles, because value is always co-created by reciprocal and mutually beneficial relationships. Precisely, “value is co-created when resources are used” (Pinho et al., 2014: 472). Hence, the notion of value co-creation is based on this fundament proposition: “the customer is always co-creator of value: there is no value until an offering is used, experience and perception are essential to value determination” (Vargo and Lusch, 2006: 44).

The conceptual framework of value co-creation recognises the centrality of encounters, such as the processes and practices of interaction and exchange within consumers and providers relationships (Payne et al., 2008). Whether the consumers’ ability to create value is based on the information, skill and operant resources that they can access and use, the providers’ one is based on the capacity to add to the consumers pool of resource in terms of competences and capabilities for creating value. Hence, encounters are crucial for boosting co-creation. Those are interactions and transactions through which parties exchange resources, competences, and practices according to the value proposition that “value is created by experience” (Prahalad and Ramaswamy, 2004: 172). Recent investigations have applied the S-D logic in complex and multi-actors service systems, developing a new version of the conceptual model (Nenonen and Storbacka, 2010; Lusch et al., 2010; Best et al., 2019). They have focused on value network (system of service system), such as “relatively self-contained, self-adjusting system of resource-integrating actors connected by shared institutional arrangements and mutual value creation through service exchange” (Vargo and Lush, 2016: 161). Therefore, the encounters among actors within the service system offer opportunities to facilitate the creation of experience each other. The same literature calls for more studies on value co-creation in complex service systems, with particular regard to actors’ engagement, factors and outcomes (Pinho et al., 2014; Petrescu, 2019).

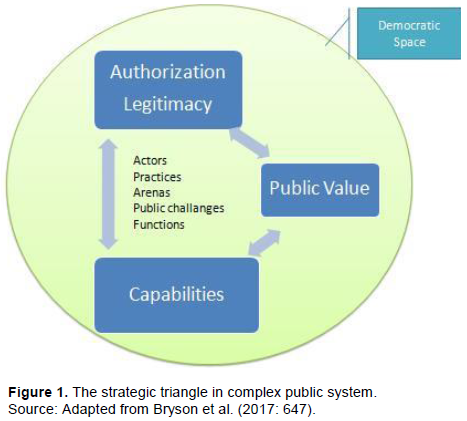

Public management literature has also suggested in-depth investigations on “public” value co-creation under a theoretical and practical perspective (Bryson et al., 2017; Voorberg et al., 2015). In fact, the social changes and the budget austerity have led governments to question the way of approaching the community in the formation of public value (Cepiku et al., 2016; Steccolini, 2019). This new approach has been conceived as a social innovation in terms of creation of long-lasting outcomes that aim to address societal needs by fundamentally changing the relationships, positions and rules among the involved actors, through an open process of participation, exchange and collaboration, thereby crossing organizational boundaries and jurisdictions (Voorberg et al., 2015: 1334). The public value co-creation as a collaborative process is developed at three levels (Petrescu, 2019: 1740): (a) individual level, contributing or receiving resources; (b) relational level, relating to the interaction and collaboration with actors; and (c) network level, where the resources are integrated through the activities of a web of actors (Cepiku et al., 2014). These levels reflect the degree of the public engagement in the co-creation of value. Moreover, the role played by the multiplicity of actors such as governments, public managers, citizens, volunteers, organizations and entrepreneurs in public value co-creation is emphasised in the in the updated version of the Moore’s ”strategic triangle” early conceptualization framework (Bryson et al., 2017: 645). Accordingly, the role of multiple actors is conceived in relation to three pillars, each of which represents a vertex of the strategic triangle. Precisely, the vertices are the following:

(a) Authorization and legitimacy of public action by various types of actors that provide resource, consensus and support;

(b) Capabilities, which include those from different actors engaged in co-creation aiming to achieve public and institutional objectives;

(c) Public value, produced in relation to the socio-economic environment, which materializes in the production of outcome objectively valid for actors’ perspective.

The triangle is embedded in the circle (Figure 1) that represents the democratic sphere conceived as “the web of values, places, organizations, rules, knowledge and other cultural resources held in common by people through their everyday commitments and behaviours, and held in trust by government and public institutions” (Benington, 2011: 32).

Focusing on citizen engagement in public co-creation, the literature distinguishes three different roles: (a) citizen as co-implementer in services, which refers to the transfer of implementing activities in the past carried out by the government; (b) citizen as co-designer, involved in the content or process of service delivery; (c) citizen as initiator who contributes to formulate specific service (Voorberg et al., 2015). The degree of citizen engagement in the creation of public value defines the service system as a relevant context, where the value is co-created through multi-actors’ exchanges (Best et al., 2019: 1710).

The systematic review on co-creation literature highlights how less attention has been paid on citizen co-design and co-implementer in co-creation process (Voorberg et al., 2015) as well as on the role played by the different actors in defining and advancing public value under strategic perspective (Bryson et al., 2017).

Aligning with the previous literature calls, this research attempts to enlarge knowledge on value co-creation at different levels of actors’ engagement and the relative outcome within public setting, with particular regard to cultural initiatives based on artification.

Artification as a process

The term artification has been firstly introduced, in the field of contemporary aesthetics, by a group of Finnish

scholars in an anthology, entitled “Taiteistuminen”, published in Finnish language (Levanto and Naukkarinen, 2005). However, the English translation of this Finnish word appeared even earlier in the Dissanayake’s article “An Ethological View of Music and its Relevance to Music Therapy” (2001), meanwhile its French version in the Shapiro and Heinich’s contribution, “Qu’est-ce que artification?, in the proceedings of the XVIIth Congress of the Association Internationale des Sociologies de Langue Française in 2004 (Shapiro, 2004). Hitherto, artification has been seen as one version of aestheticization (Naukkarinen, 2005), in its categories and uses (Korolainen, 2012) or differently as a means that transforms things into art, by making or producing art or making art to exist (Dissanayake, 2001). Later on, the special issues of Contemporary Aesthetics on “Artification” (2012) has contributed to extend this concept including processes where something that is not art gets affected by art, but it does not turn into art as traditionally acknowledged, even though it is accepted by the art world. More specifically, Naukkarinen and Saito (2012: 1) quote that:

“this neologism, ratification, refers to situations and processes in which something that is not regarded as art in the traditional sense of the word is changed into something art-like or into something that takes influences from artistic ways of thinking and producing” (our Italics).

According to these theoretical viewpoints, artification represents a frame of reference within the discussion on art and non art interplaying in various contexts. Indeed, contamination of art and artist with business, health care, education, and environmental activism does not surprise (Mennell, 1989; Naukkarinen and Saito, 2012).

The incorporation of art in these other environments of human activities facilitates change and “this change is for the better” (Naukkarinen and Saito, 2012: 1). Hence, artification has been explored as a cultural phenomenon under a multi-disciplinary perspective (Shapiro, 2019). Nevertheless, a critical overview on artification is still missing and contributions by experts of other fields of research have been called since the special issue of Contemporary Aesthetics earlier mentioned (2012). On these lenses, the Shapiro and Heinich’s work (2012), “When is Artification?” provides insights for recognizing the phenomenon in its complexity and, meanwhile, for refreshing and expanding the model by adopting a threefold simultaneous research approach: materialistic, symbolic and contextual.

Under the materialistic perspective, this research mainstream investigates conditions under which things acquire traits of what we call art and how makers become artists. It implies to map the processes through which objects, forms, and practices are crafted and perceived as art-like works.

The symbolic perspective refers to the values, underpinned in the ratification as a process, and encompassed by the art-like work. At this level, research focuses on how the latter becomes meaningful not only for experts (artists, patrons, curators, sociologists, etc.), but also for common people (Shapiro and Heinich, 2012). Indeed, the artification is an ongoing process in any environment because art is engaged in social change as well as other social activities. This is the reason why the research on that matter requires the contextualization of time, space and the observation of actors and institutions involved in the artification process.

In order to build a theory of artification, the literature calls for more inquires based on case studies, which allow capturing variations and exploring the phenomenon with a holistic perspective. At this stage of research, the literature provides a dynamic model of artification composed of 10 salient micro-processes (Shapiro, 2019). Consistently with the value network perspective, the Shapiro’s model represents artification “a process of processes” (Table 1), which engages multi-actors such as creators, critics, organizers, donors, public officials, managers and many others who contribute to create value as “art-like”.

The processes of artification have been recognized by a corpus of research on social changes trigged by painting, printing, crafts, cartoons, graffiti, tribal art, cult object, national heritage, but also cinema, theatre, breakdancing, luxury fashion, gastronomy, music as well as photography (Shapiro and Heinich, 2012). Relating to the latter, after the invention of the medium in 1839, photographers started using soft focus, giving more importance to the artistic quality of the image rather than the conventional clarity of the representation. Hence, photography has been recognized as art-like (Brunet, 2009) and, thus, has been chosen as context of the investigation (Petrescu, 2019). Aligning with the aims of the study, the research questions arisen from the previous literature gaps are formulated as follows:

Whether and how can artification trigger public value co-creation?

The revelatory case study fits with the research aim in that, by definition, it allows to enlarge knowledge on a phenomenon that has not yet been investigated or is scarcely explored (Yin, 2009). The artification case study chosen is the photo exhibition, “EXIT. Hotel fantasma in Provincia di Pavia” (EXIT. Ghost hotel in the province of Pavia), edited by Marcella Milani from October 11th 2019 to November 10th 2019 in Pavia (Lombardy, Italy). She is a well-known photo-reporter of the “Corriere della Sera”, the historic Italian daily newspaper founded in Milan in 1876. Her notoriety is mainly due to the photography, carried out as freelance, and above all to the shots of abandoned areas and places of lived life. “EXIT” represents, indeed, her third exhibition after “Mente Captus” (2017), concerning a mental hospital in Voghera (in province of Pavia) and “URBEX Pavia” (2018) on abandoned industrial areas of that city. The motivations of this research choice came out not only from the high reputation achieved by the photographer at local and national level, but also for the success of her last temporary exhibition created in collaboration with various actors operating in the same environment.

The project of Marcella Milani was sustained, in fact, by the Municipality of Pavia because of the intrinsic value embedded in her photos. Such value stems on the memory of hotels, many of which were luxury hotels, located in the surrounding spa areas of the city, as places where citizens of Pavia and tourists were used to be guested and spend relaxing time during the 60s to 70s. Thanks to the aesthetic value of the photos and the collateral events of the exhibition, as the Ghost hotel tours arranged by a local entrepreneur, the exhibition has given visibility to those places, making them attractive again.

This pioneering study is relevant under threefold perspective: (1) the context is the photo exhibition which is recognised as artification, according to the aesthetic literature before mentioned; (2) the 80 photos in exhibition transfigure imagines of abandoned hotels, many of which are auctioned, in art-like as demonstrated by the huge number of visitors achieved in the span-time of a month (4,556 visitors, about 20% of the annual average of those of the civic museums recorded in the last five years; (3) the exhibition, with free entrance, represents the public value co-created by a multi-actors engaging in the processes of this artification.

Numerous studies have shown the ability of content analysis to derive photos of visitor/tourist behaviour patterns (Zhang et al., 2019; Stepchenkova and Zhan, 2013; Balomenou and Garrod, 2019), but in this case the focus is not so much on checking whether Marcella Milani's photos are artification, but whether and how her artification has contributed to co-create, while unconsciousness, public value in a complex system and the relative outcomes.

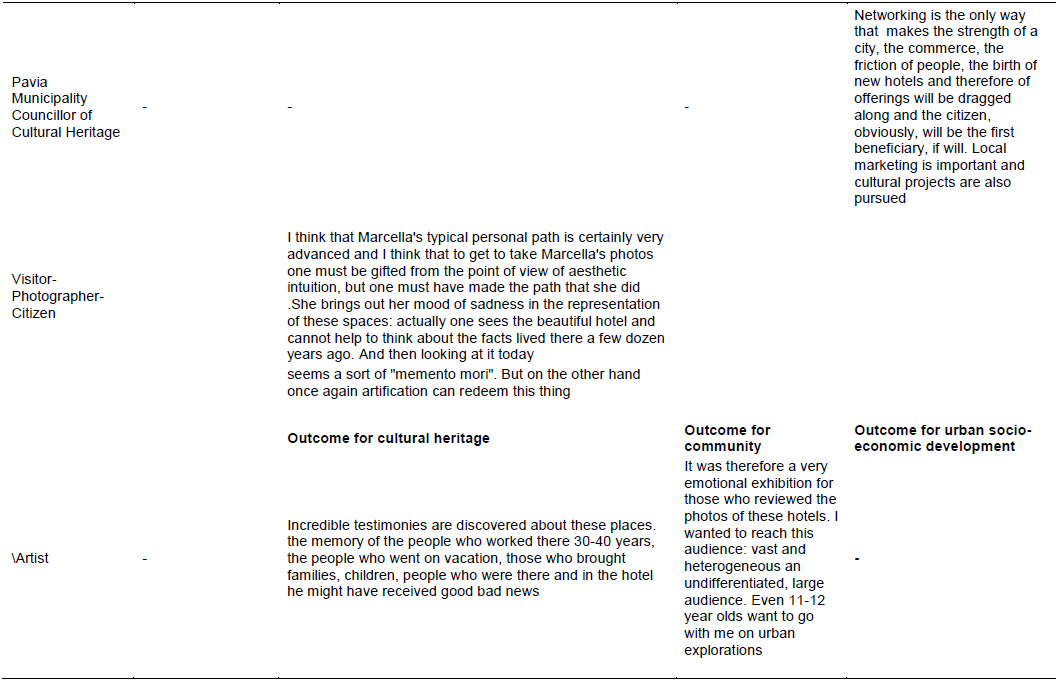

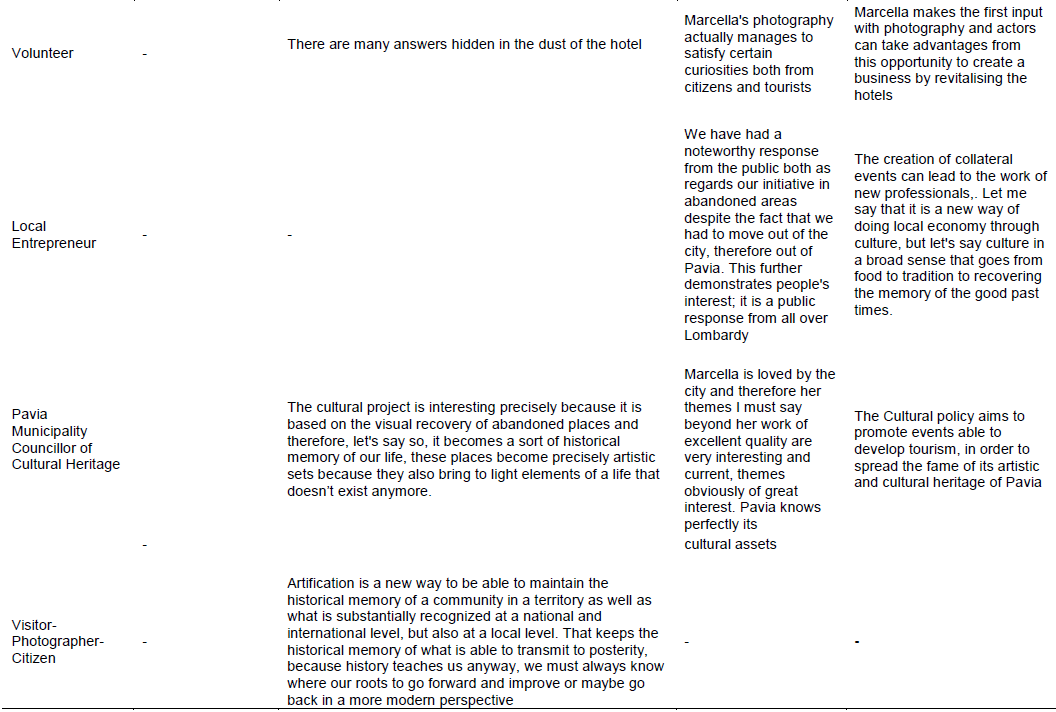

According to the content analysis method, the texts used to answer the research questions are the interviews with specific actors: the artist (Marcella Milani), the citizen who helps Milani, as volunteer, in her productions and exhibitions, the local cultural entrepreneur who arranged collateral events of the exhibition, the Pavia Municipality Councillor of the Cultural Heritage and a citizen who is a well-known photographer in Pavia too.

The interviewees have been chosen also in relation to their engagement in the co-creation of photo exhibition (Table 2). The interviews have been done a month after the end of the exhibition. Each interview, carried out individually, was conducted using a scheme of open questions in order to enable the interviewees to argue on specific topics widely and freely. The questions were formulated in such a way as to avoid the risk of shaping the answers to the research need, so to distort information and jeopardize the validity of the research (Krippendorff, 2004:

41).

The interviews have been recorded and transcribed by adopting the MAXQDA2020 program for social science-oriented data analysis. The in-vivo coding has been based on the on the conceptual categories identified by the frequencies of the words of the all texts analysed. The content analysis has identified sub-codes per any code, in accordance with the consulted literature. The textual evidence have been exposed to the interviewers in order to test the validity of the interpretation and made reliable the research results.

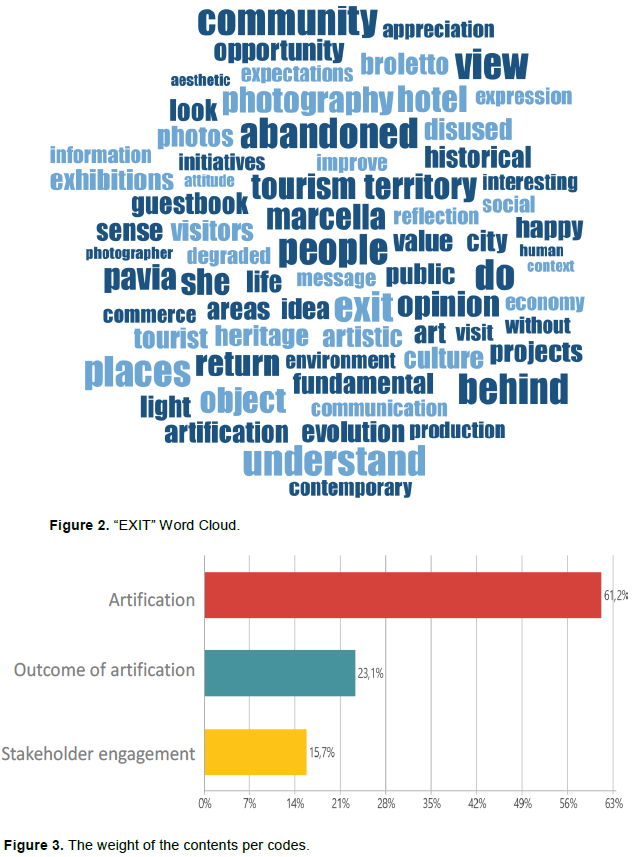

The content analysis requires the texts from which evidences are inferred. The answers to the questions have been transcribed by adopting the MAXQDA2020 program that has allowed to analyse more than 7.000 words. The latter have been reduced to 609 nouns. The word cloud with 70 meaningful words has been achieved (Figure 2).

The words with high frequency, exerted by the interview’s transcription, have enabled to identify three main codes:

(a) Artification (photograph, hotel, places, Marcella, abandoned, value, art, etc.);

(b) Actors engagement (community, people, social, visitors, city, etc.);

(c) Outcome of artification (territory, historical, projects, tourism, life, culture, etc.)

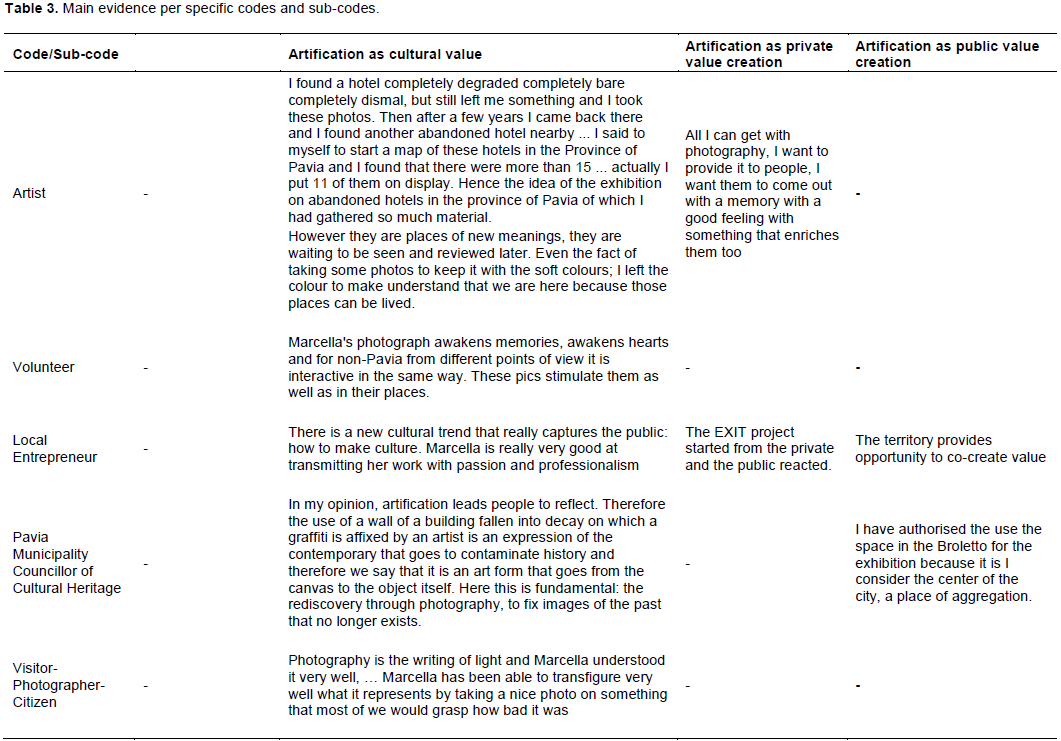

The analysis has shown the weight of the contents, referring to the previous codes, in relation to the overall texts of the interviews (Figure 3).

After having identified the main codes the analysis has adopted as keys of interpretation, the conceptual categories were derived from the value co-creation framework.

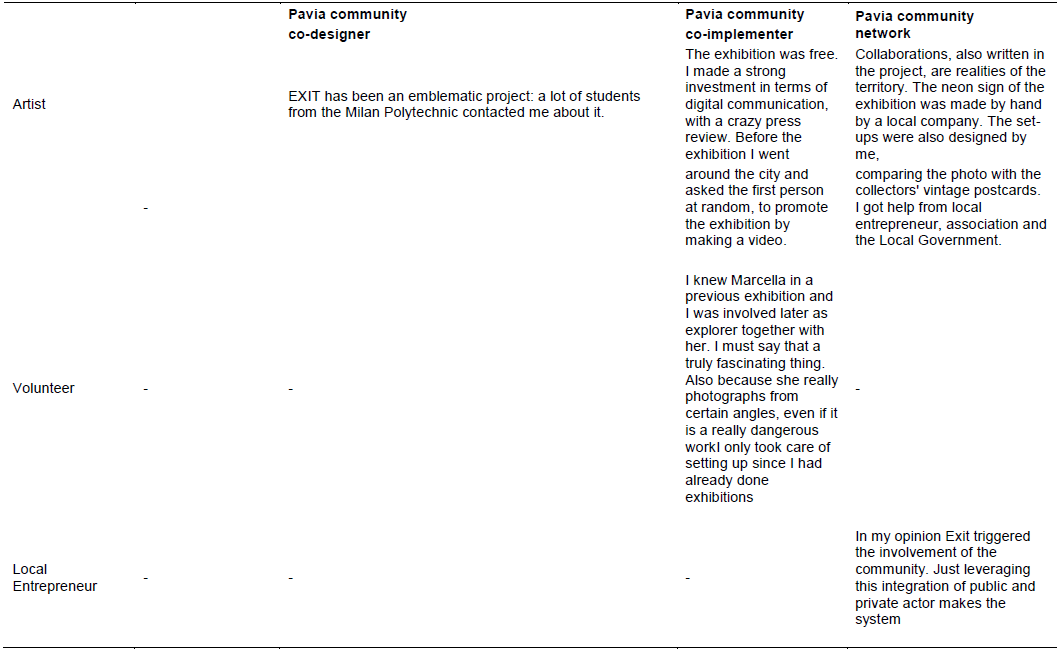

It was ascertained that the artification represents the content most discussed by the interviewees, a more detailed analysis has been carried out in relation to the meanings attributed to the value, according to the aesthetic and managerial perspectives. Precisely, the emphasis on the nature of the value sprang out by the textual evidences allowed to identify the following sub-codes (Table 3):

(a) Artification as cultural value, when the paraphrases refer to the aesthetic nature of the value as “art-like” and the relative cultural and social implication;

(b) Artification as private value creation process, in terms of value created by the artist as service provider;

(c) Artification as public value creation process, related to the benefits exchange in the encounter between the artist and the actors (that is public, community, local government).

Regarding the coding, “stakeholder engagement”, many sentences refer to different degree of citizens/actors’ engagement in co-creation (Petrescu, 2019). Hence, the sub-coding has been structured as follows:

(a) Pavia Community Co-designer refers to Marcella Milani’s work in creating value able to enhance the culture heritage of her community;

(b) Pavia Community Co-implementer, regarding the contributions of the community as consumers in the co-creation of value as experience;

(c) Pavia Community Network, relating the multi-actor’s relationship underpinned in the co-creation of the exhibition.

Many types of textual evidence are connecting to the value co-creation outcomes, which reflect the benefits each actor receives from interactions and resources integration activities (Pinho et al., 2014: 481). These have been recollected in the following sub-codes:

(i) Outcome for the cultural heritage, in relation to the impact of artification in terms of enhancing the historical value of the territory of Pavia and the memory of the community lifestyle;

(ii) Outcome for the community, regards the visitor satisfaction, their comments and their behaviour;

(iii) Outcome for urban socio-economic development, concerning the strategic opportunity to revitalise the Ghost hotels of the province of Pavia glimpsed through EXIT exhibition.

The textual evidence derived by the content analysis (Table 3) has highlighted the efficacy of the co-creation process started by a talent photographer, with the willingness to provide a relevant cultural heritage experience to the community of Pavia, her home city, and to any other target of audience. She took inspiration from territorial goods that are not more assets for its cultural heritage, but quite ruins. She was able to evoke a feeling of nostalgia for what was, for times gone by Christou et al. (2018).

The “EXIT” exhibition has been generating outcomes for the community as a cultural experience, so much to encourage excursions on site, visits of the abandoned hotels, as well as to make visible the opportunity to revitalize those areas, by activating public and private interest, glimpsing the opportunity to trigger the “tourism of the return”. This occurred in the EXIT exhibition, thanks to the patronage of the municipality and the engagement of volunteer as co-implementer, a network of actors, and visitors who had the chance to personally interact with the artist who was always present every day at the exhibition or indirectly by leaving a comment or a sign of their visit in the guest-book. The latter represents, for the artistic co-designer, a relevant tool for dialoguing with the audience of the exhibition. The efficacy of the accountability has also been underlined by the Councillor of the Cultural Heritage Sector of the Municipality of Pavia. According to the latter, the visitor satisfaction represents an interesting “thermometer” to understand the evolution of the taste of people, what they have perceived emotionally from the exhibition experience as well as to have a feedback on the public value co-created.

The content analysis results enable to answer the research questions in the context of this case study. Firstly, the knowledge of artification still appears, among the interviewees at least, relegated to the aesthetic field of culture: while its ability to transform an object into art-like is clear, there is still no awareness of its nature as a process enabling the creation of “value in use”, that is the value generated through the encounter between the provider, the consumers and other actors (Pinho et al., 2014; Vargo et al., 2008). Moreover, if the engagement of multi-actors in artification as “process of processes” is taken for granted (Shapiro, 2019), the increasing impact of a greater involvement of the community and the other entrepreneurs sprang out by this study. As the engagement of the actors increases, the public value, as the outcome emerged by the co-creation (Pinho et al., 2014), extends from the object of transformation into art to the value intended as an experience for community up to socio-economic benefit for the territory.

Hence, in relation to the research question on whether artification is able to trigger the public value co-creation, this study has demonstrated that it happens throughout encounters between the artist and the different actors of the socio-economic environment. Precisely, the artification plan proposed by the artist to the Councillor of Cultural Heritage of Pavia Municipality and the authorization of this cultural event (the “EXIT” exhibition at the “Broletto” Palace of the city), based on the knowledge of the popularity of the photographer and the cultural inclinations of the community, have legitimised the development of artification as a co-creation process (Figure 4).

Regarding how it occurs, the case study sheds light on how operationalizing artification as co-creation of value, in terms of different functions (communication, promotion, arranging collateral events, exhibition layout arrangement, etc.), resources integration between the artist and other network actors (exhibition venue, photos, guide tours expertise, press/media service, etc.) and managerial practices (project plan, guest-book and visitor satisfaction tools). These findings contribute to provide a new conceptual model based on the updated “Strategic Triangle” framework (Bryson et al., 2017). This conceptualization of the artification as a co- creation process adds insights for formulating strategy in cultural policy within the democratic sphere (Figure 4).

The contribution of this study is connected to the literature gaps within two different research fieldssuch as managerial and cultural heritage studies. The former calls for investigation on how the co-creation of value is operationalized in complex environments, while the latter for extending knowledge on artification under a multi-disciplinary perspective (managerial one included).

The definition of artification as a process of processes has made it interesting to explore the co-creation of value within this complex environment.

The contribution of this study is summarised by the conceptual model which extends the effectiveness of the “Strategic Triangle” framework also in the context of cultural policies. Artification is able to activate co-creation processes of public value through multi-actor engagement. The prerequisites of this artification co-creation model are: partly attributable to the talent and popularity of the main actor of the artification process (the artist), but also to the capability of the local authority (the Councillor of Cultural Heritage) to understand the cultural inclinations of the community in order to support and stimulate them, legitimizing artification project. These conditions boost artification as a co-creation process, ​​with practical implications in the field of art, business, and cultural policies.

Relating to the former, if the artist would like to enhance the work art-like, it is necessary to adopt managerial logics (networking, business planning) and tools (project plan, accountability practice). These capabilities are useful to achieve legitimation and authorization by the local government and, consequently, to activate the co-creation of public value.

On the entrepreneurial side, artification can trigger cross-fertilization processes based on innovation in cultural and creative sector, as well as in the third sector. Moreover, in relation to the type of object transformed in art-like, the artification co-creation process can open up new opportunity of social-economic revitalization of provincial areas.

With regard to the cultural policy, artification enables policy makers to provide the extended outcome of public value by legitimating the artification proposals of artists capable to interpret, with modern sensitivity, the signs of the times of the local community.

The implications underpin the limitations of this research, identified in the biases implicated in the interviews and the content analysis, as well as in the use of a single case study. Therefore, the conceptual model requires more investigations, in different kind of artification practices, in order to extend its generalisation. Further research on value co-creation within other cross-setting environment is also welcomed.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

The author is grateful to Marcella Milani, art-photographer, and all the interviewees (the volunteer, the Pavia Municipality Councillor of Cultural Heritage, Tourism, Events and Territorial Marketing, the Cooperativa Progetti Co-founder, and the photographer/video maker) who provided an important contribution to the development of the research. Special thanks also go to the reviewers and the editors of AJBM for the insightful recommendations and suggestions provided in order to improve the manuscript for publication.

REFERENCES

|

Alford J, Hughes O (2008). Public Value Pragmatism as the Next Phase of Public Management. The American Review of Public Administration 38(2):130-148.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Alonso JM, Andrews R, Clifton J, Diaz-Fuentes D (2019). Factors influencing citizens' co-production of environmental outcomes: A multi-level analysis. Public Management Review 21(11):1-26.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Balomenou N, Garrod B (2019). Photographs in tourism research: Prejudice, power, performance and participant-generated images. Tourism Management 70:201-217.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Benington J (2011). From Private Choice to Public Value?" In Public Value: Theory and Practice, edited by Benington J, Moore MH, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 31-49.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Best B, Moffett S, McAdam R (2019). Stakeholder salience in public sector value co-creation. Public Management Review 21(11):1-26.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bovaird T, Van Ryzin G G, Loeffler E, Parrado S (2015). Activating Citizens to Participate in Collective Co-Production of Public Services. Journal of Social Policy 44(1):1-23.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bozeman B (2007). Public values and public interest: Counterbalancing economic individualism. Georgetown University Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Brunet F (2009). Photography and literature. Reaktion Books.

|

|

|

|

|

Bryson J, Sancino A, Benington J, Sørensen E (2017). Towards a multi-actor theory of public value co-creation. Public Management Review 19(5):640-654.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cepiku D, Mussari R, Giordano F (2016). Local governments managing austerity: Approaches, determinants and impact. Public Administration 94(1):223-243.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cepiku D, Mussari R, Poggesi S, Reichard C (2014). Special Issue on Governance of networks: Challenges and future issues from a public management perspective editorial. Journal of Management and Governance 18(1):1-7.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Christou P, Farmaki A, Evangelou G (2018). Nurturing nostalgia? A response from rural tourism stakeholders. Tourism Management 69:42-51.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dissanayake E (2001). An ethological view of music and its relevance to music therapy. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy 10(2):159-175.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dostoevsky F (2010). The Idiot. London: Alma Classics.

|

|

|

|

|

Edvardsson B, Gloria N, Min CZ, Firth R, Ding Y (2011). Does Service-Dominant Design Result in a Better Service System? Journal of Service Management 22(4):540-556.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hodgkinson IR, Hughes P, Hughes M, Glennon R (2017). Does Ownership Matter for Service Delivery Value? An Examination of Citizens' Service Satisfaction. Public Management Review 19(8):1206-1220.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Korolainen K (2012). Artification and the drawing of distinctions: An analysis of categories and their uses. Contemporary Aesthetics 1(4):1-14.

|

|

|

|

|

Levanto Y, Naukkarinen O (2005). Taiteistuminen. Taideteollinen korkeakoulu.

|

|

|

|

|

Krippendorff K (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

|

|

|

|

|

Lusch RF, Vargo SL, Tanniru M (2010). Service, value networks and learning. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 38(1):19-31.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mennell S (1989). Norbert Elias. Civilization and the Human Self-Image. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

|

|

|

|

|

Miller RF (1981). Dostoevsky and The Idiot: Author, narrator, and reader. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Moore MH (1995). Creating public value: Strategic management in government. Harvard University Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Naukkarinen O (2005). Aesthetics and Mobility-A Short Introduction into a Moving Field. Contemporary Aesthetics 1(1):1-3.

|

|

|

|

|

Naukkarinen O, Saito Y (2012). Artification (Special Volume). Contemporary Aesthetics 1(4):1-7.

|

|

|

|

|

Nenonen S, Storbacka K (2010). Business model design: conceptualizing networked value coâ€creation. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences 2(1):43-59.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ng ICL, Vargo SL (2018). Service-Dominant (S-D) Logic, Service Ecosystems and Institutions: Bridging Theory and Practice. Journal of Service Management 29(4):518-520.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Payne AF, Storbacka K, Frow P (2008). Managing the co-creation of value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 36(1):83-96.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Petrescu M (2019). From marketing to public value: Towards a theory of public service ecosystems. Public Management Review 21(11):1-20.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Pinho N, Beirão G, Patrício L, Fisk RP (2014). Understanding value co-creation in complex services with many actors. Journal of Service Management 25(4):470-493.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Prahalad CK, Ramaswamy V (2004). Coâ€creating unique value with customers. Strategy and Leadership 32(3):4-9.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Shapiro R (2004). Qu'est-ce que l'artification? In proceedings of the XVIIth Congress of the Association Internationale des Sociologies de Langue Françoise.

|

|

|

|

|

Shapiro R, Heinich N (2012). When is artification? Contemporary Aesthetics 1(4):1-9.

|

|

|

|

|

Shapiro R (2019). Artification as Process. Cultural Sociology 13(3):265-275.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Steccolini I (2019). Accounting and the post-new public management: Re-considering publicness in accounting research. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 32(1):255-279.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Stepchenkova S, Zhan F (2013). Visual destination images of Peru: Comparative content analysis of DMO and user-generated photography. Tourism Management 36:590-601.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Vargo SL, Lusch RF (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing 68(1):1-17.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Vargo SL, Lusch RF (2006). Service-dominant logic: What It Is, What It Is Not, What It Might Be. In The Service-Dominant Logic of Marketing: Dialog, Debate and Directions, (eds) Lusch RF, Vargo SL, Armonk: M.E. Sharpe Inc., pp. 43-56.

|

|

|

|

|

Vargo SL, Maglio PP, Akaka M A (2008). On Value and Value Co-Creation: A Service Systems and Service Logic Perspective. European Management Journal 26(3):145-152.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Vargo SL, Lusch RF (2016). Institutions and Axioms: An Extension and Update of Service-Dominant Logic. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 44(1):5-23.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Voorberg WH, Bekkers VJJ, Tummers LG (2015). A Systematic Review of Co-Creation and Co-Production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Management Review 17(9):1333-1357.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Yin RK (2009). Case study research: design and methods. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.

|

|

|

|

|

Zhang K, Chen Y, Li C (2019). Discovering the tourists' behaviours and perceptions in a tourism destination by analyzing photos' visual content with a computer deep learning model: The case of Beijing. Tourism Management 75:595-608.

Crossref

|

|