Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

South Africa's (SA) history of apartheid produced racial inequality that was entrenched for centuries. After 1994, the goal of the new government was to transform the workplace. Numerous affirmative action (AA), legislation, policies, and procedures enforced organisational transformational obligation and compliance. Studies in SA indicate a slow pace of transformation. The financial sector may be paying lip service to affirmative action legislation; setting racially balancing targets for management structures yet not achieving them. The purpose of this paper is to explore existing literature on transformational leadership and AA progress in the SA financial sector to propose an AA Transformational Model. The research method employed was abstract qualitative content analysis method. Selected accredited journal articles were analysed as per the paper keywords for emerging trends on the topic. Findings indicate lack of leadership in transformational implementation, leadership commitment, and management motivation for accelerated transformational targets and strategies. The paper theoretically adds to the body of knowledge on workforce transformational leadership. The practical contribution of this paper is the proposed AA Transformational Model for the SA Financial sector to be proactive in their AA transformation.

Key words: Racial discrimination, racial equity, employment equity, black employees, transformation, leadership, South Africa, affirmative action.

INTRODUCTION

This paper draws upon different existent theories to discuss or to understand the lack of progress in implementing changes in the South African (SA) financial sector about transformation, especially AA transformation. From a theoretical perspective, the information extracted from theory allows the researcher to propose a model or a framework. In addition, the implementation of AA and insights into the value of the country, continent, and world economy and society are expected to make practical contributions. There is a gap in the literature in that research on AA in terms of what has historically been done on the achievement of targeted numbers. There is also very little research being done about the opinions of employees regarding the implementation of AA in the workplace. This research, therefore, endeavoured to bridge this gap using the abstract qualitative content analysis method. The findings reveal that even with the introduction of laws such as the SA Constitution, the Employment Equity, and the Broad-Based Economic Employment, discrimination in the workplace is continuous, and the implementation of these laws has not been effective. Another significant finding is that the pace of transformation is slow due to the lack of commitment of top leaders and managers in the private sector and the lack of enforcement by the government. AA has nothing to do with the employment or progress of incompetent candidates or allowing organisations to accept unreasonable adversity (Roman and Mason, 2015). AA should be about taking the steps required to confirm that able, Black individuals are employed, advanced, and retained fairly (Roman and Mason, 2015). Affirmative Action is a policy approach intended at constructing a representative and multicultural country in which fairness and parity were assured to groups and citizens (Katiyatiya, 2014). Thus, AA transformation in SA is usually conceptualised as the quest of parity and henceforth its reason is both to remedy historical unfairness and expand the upcoming aptitude pool of the country (Katiyatiya, 2014).

The Employment Equity Act No. 55 of 1998 and the implementation of AA transformation are essential steps and have their place in rectifying the historical inequities and resulting in a diverse labour force within the private and public sectors in the country (van der Bank et al., 2015). For this study, AA leadership means that decision-making and senior management commitment to AA transformation is required for the successful implementation of the policy (Booysen, 2007). This could be done through management changes and moves towards a more representative and inclusive workplace (Booysen, 2007). According to Booysen (2007), organisa-tional change must be systemic and the implementation of the AA is just the start of the transformation process. AA transformation application needs to be backed by consistent employment practice plans concentrating on employee training and development, inclusive practices, and organisational culture change (Booysen, 2007). If the leader is stereotyped due to the old traditional norms, it may lead to prejudice, and the AA transformation will not be part of his vision.

The purpose of this paper is to theoretically explore the leadership of AA transformation in the SA financial sector and to practically propose a strategic AA Transformational Model for the sector. On a practical level, the paper promotes diversity as a diverse workforce promotes creativity, innovation, productivity, economic growth, and quality of decision making in teams (Wambui et al., 2013; Galinsky et al., 2015). The world's increasing globalism needs more teamwork among people from different cultures, beliefs, and backgrounds than ever before (Wambui et al., 2013). Adopting, expanding, and taking advantage of workplace diversity has become an essential asset for management today (Wambui et al., 2013). Multiplicity also helps underrepresented individuals to take chances (Galinsky et al., 2015). Transformation is about creating a diverse workforce. The impetus of diversity lies in valuing multiplicity which requires top leadership commitment towards a diverse workforce (Kundu et al., 2015). According to Mazibuko and Govender (2017), a diversity management strategy should be planned and designed with clear goals that promote transformational compliance as well as organisational transformational strategy.

The exploration of understanding AA leadership in the financial context looks at how the leadership styles lend themselves to either high or positive AA leadership or low or obstructive AA leadership. The financial context is seen as consisting of banks and insurance companies; however, in this study, the financial context refers to the banking industry. The paper employs a theoretical pers-pective to extract relevant existing information to propose a practical implementable model or strategy. In South Africa, the banking industry contributes to 20% of the gross domestic product (GDP), and is the third-largest employer, employing over 10% of the population (Ifeacho and Ngalawa, 2014). The structure of the SA banking industry is a unique, highly sophisticated financial sector and is dominated by four major banks (Mishi et al., 2016). The Amalgamated Banks of South Africa Limited (ABSA), First National Bank (FNB), Standard Bank, and Nedbank together dominate the SA banking industry (Ifeacho and Ngalawa, 2014). Research indicates that high conso-lidation levels in the banking industry do not indicate a lack of but rather increase competition (Simatele, 2015).

Businesses within SA face devastating responsibilities due to past harmful bigotry and inequality (Reddy and Parumasur, 2014). Prolonged apartheid or separateness and divide-and-rule strategies relegated all segments of the country's citizens' lives. Most of the population, Black people, were denied decision-making power and economic involvement (Reddy and Parumasur, 2014). Almost two decades after democracy in South Africa, questions of tribal leadership, clan socioeconomic rights, and ownership of land are still as challenged, as they were twenty years ago (Bock and Hunt, 2015). Democracy ushered in new regulation towards radical racial transformation and inclusion for all citizens to actively participate in the leadership of the country at all levels of society and economics. These are the fundamental transformational legislation that businesses must comply with within SA: Constitution of South Africa, 1994; Labour Relations Act, 1995; Basic Conditions of Employment Act, 1997; Employment Equity Act, 1998; Skills Development Act, 1998; and the Skills Development Levies Act, 1999 (Booysen and Nkomo, 2010).

The greatest strength of South Africa's Constitution is that it is one of the utmost progressive documents in the world, which has received countless admiration globally (Booysen and Nkomo, 2010). It protects the human rights of all the people in the country and it confirms the democratic values of human dignity and freedom (Booysen and Nkomo, 2010). The SA Constitution was designed to integrate fairness and AA transformation to redress past inequalities done to Black people yet promote opportunities for its entire people to grow economically (Lee, 2016). The SA Bill of Rights, the Employment Equity Act of 1998 (EEA), and the Labour Relations Act of 1995 consider partial bias and prejudice, either openly or passively, as detrimental and illegal employment practices (Horwitz and Jain, 2011). Racial and ethnic inequity is a frequent unhealthy and unpleasantly characteristic of the labour force in many countries (Op't Hoog et al., 2010). South African human resource management (HRM) and employment relations management (ERM) is presently under compulsion to restore historical ethnic disparity. Due to the past of segregation, Employment Equity (EE) and the balance must be established through far-reaching EE, AA transformation, and Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (B-BBEE) strategies (Op't Hoog, Siebers and Linde, 2010). According to the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC, 2016), SA has one of the most unfair workforces in the world. The incidence of prejudice in the private sector remains significantly high. This applies to the financial services sector as well. After 26 years of democracy, it is now the right time to establish the level of transformational progress achieved in the country, especially in the financial services sector.

The research problem and motivation for this paper arose from the gap in the literature on what transfor-mational goals were achieved towards racially equitable employment opportunities in SA workplaces. More specifically, an intensive literature review of the current situation provides a more accurate and authentic view of the socio-economic landscape, especially with regards to transformation in affirmative action measures. This paper focuses on AA transformation in the SA financial context. The research questions explored in this paper are as follows: Does South African employment legislation promotes affirmative action? Do contemporary leadership styles promote affirmative action? Do South African financial services leaders and managers promote affirmative action? What model can SA financial managers utilise to enhance AA transformation?

This study contributes to theory by adding to the body of knowledge on transformation, AA, and AA leadership in SA and the financial sector. In addition, this study contributes to the literature by providing an AA Transformational Model for the SA Financial Sector, thus guiding managers and leaders on how to create a harmonious representative workforce including all the people in South Africa.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Affirmative action in South African legislation

The Employment Equity Act of 1998 requires organisations to set numerical goals, implement plans to eliminate unfair discrimination of Black people in employment and vital positions, as well as recruit, retain, train, develop and advance previously disadvantaged individuals (Horwitz and Jain, 2011). The goal of AA in South Africa is to guarantee that Black people (Africans, Coloureds, and Indians) including women and people living with disabilities, have the same constitutional rights and the same prospects as its previously advantaged White citizens (Archibong and Adejumo, 2013). Models of redress, such as AA transformation and B-BBEE, are strategies to engage in uplifting citizens who were disadvantaged during the apartheid era, through a string of political and social compromises (Kotze, 2012; Rotich et al., 2015). The main aim of the B-BBEE regulation was to drive the economic empowerment of all Black individuals, with a specific focus upon women, workers, youth, people with incapacities, and persons living in rural and city districts, through extensive but combined socioeconomic tactics (SABPP, 2017). In its position paper on AA transformation, the SA Board for People Practices (SABPP, 2012) found that the slow rate of transformation is due to the lack of motivation of top management towards AA transformation in some companies, and especially in medium and large corporations. Affirmative action leadership in a medium and large organisation is therefore weak. According to the acting chairperson of the Commissioner of Employment Equity (CEE), the trends in 2014 and 2015 show a relatively slow pace of AA transformation (Department of Labour, 2015). Research reveals that the pace of AA transformation is seemingly blocked in the uppermost levels of leadership and management in the corporate sector of South Africa (SABPP, 2017). This slow pace of AA transformation also applies to the banking industry in South Africa.

To date, the 19th Commission for Employment Equity (CEE) annual report 2018-2019 reveals that White people remained dominant in top management positions between 2016 and 2018 (Department of Labour, 2019). The report shows that in 2016 there were 68.5% of Whites in top management positions, 67.7% in 2017, and 66.5% in 2018 (Department of Labour, 2019). There were 14.1% Africans in top management in 2016, 14.3% in 2017, and 15.1% in 2018. In 2016 there were 4.9% of Coloureds in top management positions, in 2017, 5%, and in 2018, 5.3%. There were 8.9% Indians/ Asians in top management positions 9.4% in 2017, and 9.7% in 2018 (Department of Labour, 2019). There were 3.4% Foreign Nationals in top management positions in 2016, 2017, and 2018 respectively (Department of Labour, 2019). The CEE report, therefore, shows a little transition in the African and Coloured management representation (Department of Labour, 2019).

The Employment Equity report for 2016-2017 reveals that in the South African private sector, 50.8% of senior leadership positions are occupied by White males while 10.9% are held by White women. In contrast, only 9.2%of senior leadership positions are held by African males and 2.8% by African women (Department of Labour, 2017).

This report also shows a weak AA leadership in the private sector due to the low levels of African leaders in senior leadership positions. This will also apply to the SA financial sector. The B-BBEE idea can be traced back to the Freedom Charter of 1955, which claimed that her citizens who work her land shall take part in SA's wealth (Chabane et al., 2006). In many organisations, considerable auctions of shares have been sold to Blacks who, in almost all instances, did not have the necessary money to obtain the interest being sold (Mbembe, 2006). According to Alexander (2006), B-BBEE has been used to benefit a few well-known party-political leaders who were leaders in the fight against apartheid. Coomey (2007) argues that White funds have blessed a few politically connected Blacks to front as security against the Black deprivation class, though huge amounts of White entrepreneurs continue to benefit silently. The outcomes of B-BBEE have been varied and in several ways; for the government especially, B-BBEE achievements are disappointing. Research reveals that a greater number of big and medium-size corporations continue to remain under White male leadership (Southall, 2014; SABPP, 2017). The application of the principle of 'Equal Pay for Work of Equal Value' is not only an ethical subject but a civil rights matter, which requires a will and commitment from top management in the workplace to put in place strategies and implementation plans geared towards addressing the continuing pay disparities experienced by most workers in the country (SABPP, 2017).

Explanations provided for why AA transformation has not been successful enough include stereotyping, dishonesty, favouritism, nepotism, and lack of enforcement, as well as sabotage by previous benefactors of segregation (Archibong and Adejumo, 2013). A myth about EE is that it is reverse discrimination that gives special treatment to Black people and women (Naidoo and Kongolo, 2004). Naidoo and Kongolo (2004) state that gender stereotyping has caused most Black women to be hired in areas such as education and health in which they perform only in lower levels of work, with very few in top management positions (Naidoo and Kongolo, 2004). Gender stereotyping significantly obstructs the career progressions of many women seeking management positions (Tabassum and Nayak, 2021). Stereotyping is originally shaped in infancy and education, yet workplaces influence the development of stereotypes through various practices such as recruitment, promotion, and establishing a branded culture of the organisation (Tabassum and Nayak, 2021). Stereotyping also indicates that in the SA financial sector, some White employees regard Black employees as token appointments who are incapable of doing their job (Booysen, 2007).

At the end of apartheid, there was 30 to 40% redundancy amongst primarily Black employees, great amounts of poverty within the Black sections of the public, and 27% illiterate levels in Black communities (James, 2009). Since the emergence of democracy in 1994 South Africa has made notable advances and progress in winning over the talent management legacy of the past (Mummenthey, 2010). Despite some achievements, insufficient levels of skills among the better part of the formerly deprived individuals have dangerously increased unemployment levels, especially amongst young people (age 15-35). The youth remains one of the country's highest and most stubborn challenges, presenting socioeconomic instability for all its citizens (Mummenthey, 2010). The Skills Development Act (1998) was introduced to offer training and development to employees that lead to recognised employment (Aigbavboa et al., 2016). This skills act highlights the necessity to change skills development through investment, spinning the place of work into a sovereign setting, refining the meaning of teaching and knowledge for the workforce. This act was motivated by an evolving need for educated, qualified, and experienced talent (Rotich et al., 2015; Aigbavboa et al., 2016). The Skills Development Act aimed to increase the abilities of the South African citizens, boost companies participating in educational initiatives and refine the employment prospects of Previous Disadvantaged Individuals (PDIs). Any workplace prejudicial racism to PDIs was outlawed and instead, as a redress, those deprived were being compensated through training and development opportunities (Aigbavboa et al., 2016).

South Africa has made noteworthy improvements and development in disabling the skills deprivation legacy of the past since the start of democracy (Lolwana et al., 2015). Regardless of this advancement, low levels of skills among most of the PDIs and persistently high joblessness rates, particularly amongst the young 15- to 35-year-olds, continue to be one of the state's most persistent worries and one of the highest obstacles to a better future for all (Lolwana et al., 2015). Youth includes approximately 70% of the jobless in the country. Furthermore, South Africa still has a very huge populace living in the countryside regions (approximately 45%). Usually, rural residents do not obtain as decent amenities as their city counterparts (Southall, 2014; Lolwana et al., 2015). Hence, the rural youth are the most deprived as they are further removed from training prospects and job opportunities (Lolwana et al., 2015).

Leadership through change

Change is an inevitable feature of life and in the 21st century. It has become vital for all organisations, societies, and individuals to withstand the ever-changing world that surrounds us (Mehta et al., 2014). Hence, effective change management is the duty of every individual, especially for leaders and managers. Gning and Yazdanifard (2015) assert that decision-making makeover refers to the transformation of a business from its existing state to its expected future state. Multiple organisational tactics are employed to assist employees with the progress of change. Management is a key part of managing change processes and their attitude forms the key to successful organisational transformation (Gning and Yazdanifard, 2015). Businesses including banks are looking for a management team that gives the company confidence in achieving its objectives. Effective managers cleverly delegate authority to line managers and team leaders who localise AA transformation and change, thus surpassing the commotion of the change process. Effective organisational change leaders forego short-lived benefits and earnings and employ multiple strategies to improve the incomes and work conditions for all employees (Kishore and Nair, 2013). With worldwide economic competitiveness growing, visionary leaders creatively construct strategies that allow a competitive advantage using a multi-talented workforce, diverse in race, culture, age, skills, and competencies (Curtis and Cerni, 2015).

Nagendra and Farooqui (2016) argue that the main purpose of a leader is to influence, guide, and motivate others to accomplish specific duties. Managers encourage his/her juniors for proficient attainment and completion of the specified goals. Weak leadership is a subject that is central to many company disasters, governance issues, and regulatory failures; however, on the flip side, strong leadership is unavoidable for the re-establishment of good, ethical conduct in businesses (Doraiswamy, 2012). Lee (2011) states that capable management is a strength in leadership that is required to deliver equity in workforce traditions that discriminated against Black people. A Leader that delivers equality in the workplace constitutes a strong AA leadership. A capable, strong management team is required to inspire meaningful equity as well as authentic equality. This raises questions on what type of persons can possess change management skills, who will occupy transformational leadership positions, and how the job of leading a company may be performed to produce the kind of endorsed values required to allow a deep appreciation of diversity. Visagie and Linde (2010) describe effective leadership as the ability to understand and influence the activities of a person or a group by motivating employees to cope with difficulties, struggles, and challenges that arise daily in work and life. Evolving business leaders of today recognise that leadership’s competencies, styles, attitudes, and values become significant for achieving business strategies and goals.

The three main leadership styles, namely, transactional leadership style, transformational leadership, and transcendental leadership are addressed as part of transformational leadership. These leadership styles either help or are not helping with the effective implementation of AA transformation based on their characteristics. According to Raghu (2018), the role of leadership is important in promoting affirmative action, and leaders must make sure that there is a strategy and execution plan in place to deliver the objective.

Transactional leadership is a type of leadership style that focuses on using executive rule and sincere power in the business. These leaders emphasise job accountability, job-related ideals, and employee obedience (Ng and Sears, 2012). Transactional leaders are more involved with operational or mechanical justice, displaying a by-the-book type of leadership. They comply with diversity laws due to usual natural forces such as AA guidelines, however, they are not prepared to do anything more than what the law prescribes (Ng and Sears, 2012). Leaders who adopt a transactional leadership style will therefore only implement AA to a certain extent but they will not exceed AA targets or expectations. They will only comply with the law and not go beyond what is expected from them. With transactional leadership, authority and accountability exist and are visible in his/her control, top-down approach (McCarthy et al., 2010). Transactional leadership can be considered as a business deal affiliation between two dealings to reach a sequence of specific assignments, complete a chain of demands, situations, and benefits or dispense punishment (de Vries and Korotov, 2010). Such dealings are common amongst managers and their subordinates, for example, company owners pay salaries for work completed by workers (Hirtz et al., 2007).

A transactional leader accompanies people where they need to go, while a transformational leader leads persons where they do not logically yearn to go, but where they must be (de Vries and Korotov, 2010). In a transactional approach, the leader emphasises principles such as honesty, reliability, and accountability to their purpose (Naji et al., 2014). Transactional management is inclined to be job-oriented rather than people-oriented. They improve work efficiency and subordinates are assisted to know their job obligations and discover their goals (Long, Young and Chuen, 2016). According to Odumeru and Ifeanyi (2013), transactional leaders provide a provisional reward (such as a compliment) when goals are reached on time, in advance, or to keep subordinates working at a decent pace at dissimilar intervals through conclusion. Transactional leaders also use conditional warnings (such as deferrals) when work excellence or competence drops lower than the established benchmarks or goals, or when job requirements are not met at all (Odumeru and Ifeanyi, 2013).

In the transactional management model, superiors assign authority to representatives who pacify others and thus occasionally gain promotion within the company (Ruggieri and Abbate, 2013). A transactional leader is inflexible in his/her anticipations about the employment association and considers that the junior's responsibility is only to follow their orders (Umme et al., 2015). Based on the characteristics of this leadership style, the leader who adopts this style will merely comply with AA legislation but will in all probability not be great at leading transformation in the banking sector or private sector. Transformational leadership is described by Kunnanatt (2016) as an exciting, astute symbol that thrills subordinates by feeding their higher-order longings and engaging them in the managerial decision-making process. Through powerful negotiation tactics, transformational leaders encourage individuals to surpass their selfishness for the advantage of the group and the company (Kunnanatt, 2016). According to Lyndon and Rawat (2015), transformational leaders endeavour to achieve the follower's needs, who in turn will accomplish their employment requirements. Transformational leaders form a genuine trust between power and subordinates. Tangible transformation occurs only when there is visible top-down understanding and management encourages bottom-up determination. There must be a compromise towards change implementation; this is contrary to change opposition (Basu, 2015). Transformational leaders are motivated by equality, work diversity, shared justice, and they are inspired to achieve workforce diversity as it is the ethical and right thing to do (Ng and Sears, 2012). According to Ashikali and Groenewald (2015), there is a stronger correlation between transformational leadership and diversity management. Because of these characteristics, a leader who adopts a transformational leadership style will in all probability be great in implementing AA in the workplace. This will also apply to leaders in the financial services sector.

This type of leadership is considered as a multidimensional, multiplicity meta-form, which has a positive impact on employee purposefulness, eagerness, success, and natural transformation (McCarthy et al., 2010; Ashikali and Groenewald, 2015). According to Chao (2017), in terms of setting executive targets, the challenge for transactional leaders is that they set objectives for subordinates to follow; while the transformational leader and subordinates work together to plan and attain the targets. Transformations leaders endlessly reinvent themselves, they remain flexible and adaptable, and they advance those near to them (de Vries and Korotov, 2010). These leaders are convincing, they endeavour to create an appearance of hope, and they offer an incentive to followers. They encourage employees to challenge the status quo and manifest an obligation for uniqueness. They are role models to their followers and are respected, appreciated, and reliable (Rehman and Waheed, 2012). Uncertainty is a noticeable challenge in the transformational leadership process (Umme et al., 2015).

Transformational leadership is censured for lacking concerns of decency and morals (Liu, 2007). Transformational leadership is related to romanticised inspiration or charm, intelligent motivation, distinct analysis and is centered on common respect with shared dreams and exchanges of philosophies (Sudha et al., 2016; Lam and O'Higgins, 2012). This style of leadership tries to put into alignment the interest of the followers with those of the organisation (Validova and Pulaj, 2016). It acts as a link amongst leaders and groups to cultivate a perfect appreciation of follower wellbeing, standards, and inspirational levels (Nagendra and Farooqui, 2016). Transformational leaders are visionary and they have excellent communication skills, inspiring their followers, all of which are more appropriate for leading and executing AA transformation (Raghu, 2018).

Transcendental leadership contends that for leadership to realise prominence, it must be value-centred and sanctified (Havenga et al., 2011). Transcendental leaders have an internal or intrinsic locus of power and control. Extrinsically, essentially transcendental leaders motivate groups and stimulate employees, even in volatile arenas and economies (Liu, 2007). Transcendental leaders live and make visible the company values; thus they achieve planned innovations that stand the test of time (Kishore and Nair, 2013). They are concerned with the good of the organisation and its employees. They embrace change and encourage colleagues to buy into their vision while they nurture the needs and growth of others (Naji et al., 2014). Transcendental leadership incorporates just, ethical and spiritual philosophies to validate leadership as well as subordinate conduct (Isebor, 2018). This style of management places the running of social affairs beyond oneself in a managerial context (Nair, 2016). Transcendental leadership projects a complete, courteous, and united resolve, seeking solutions through collaborative discussions and understanding of people, profits, and the planet (Nair, 2016). Transcendent leaders exhibit multidimensional mindfulness. The more open the leader's consciousness is to perceive all employees in all work stages, the more influence he or she will have on their external setting (Stebbins, 2017).

Transcendental leadership, grounded in servant leadership, offers a pathway to increased trust that is necessary for global socioeconomic sustainability (Gardiner, 2011). Transcendental leadership offers a more holistic and collaborative executive procedure for the financial, societal, and ecological segments of businesses. They often go further than meeting the singular goal of increasing the bottom line of the business to include increasing the incomes, benefits, and rewards for people, societies, and the earth (Gardiner, 2011). Transcendental leadership emphasizes what is virtuous for civilisation, the atmosphere, investors, and financial and common contributions (Swierczek, 2014). Transcendental leaders co-create a shared dream leading to a superior creation. They also motivate and inspire their employees to strive to achieve that dream (Swierczek, 2014). Contemporary business executives must lead the organisation at these three levels if they are to practice transcendental management: lead by example (identity); lead through followers (others); and lead the business strategy towards transformation, evolution, and growth (corporate) (Crossan and Mazutis, 2008).

As a leader who can function within and between the echelons of personality, others, the company, and civilisation, transcendental leaders will be able to successfully manoeuvre in the present unpredictable place of work (Sturm and Vera, 2011). The literature presents a gap on how transcendental leaders identify and manage obstacles and difficulties, such as transformational change, promoting AA transformation, and establishing a diverse workforce. Furthermore, limited research is available on how these transcendental leaders influence, achieve and impact workforce spirituality (Isebor, 2018). Leaders that adopt a transcendental leadership style are great at implementing AA. Raghu (2018) identified three key roles of leaders in implementing AA to inspire their followers in under-standing the value of AA transformation implementation through open communication and showing genuine commitment towards the implementation of AA; to promote the application and implementation of the AA plan by eradicating obstacles to implementation and to provide funds to assist affirmative action, and to create a culture of AA transformation through incorporating AA into the business model and cascading the significance and commitment through all levels in the organisation.

Diversity Leadership values In South Africa

The word '[GM1] diversity incites strong emotive responses in some people and causes managers and administrators to immediately consider measurement concepts such as transformational targets and quotas. This in part arises from a limited understanding of how and why individuals protected under transformational legislation and strategies should be valued. Diversity management values include managing workforce variances such as tribe, sex, culture, language, and ethnicity (Herring, 2009). Diversity comprises all kinds of distinct variances, such as background, age, faith, incapacity position, geographical position, character, skills, competencies, reproductive choices, and an innumerable of other individuals, demographic and managerial characteristics (Herring, 2009; Clark, 2015). Diversity leadership is different for every business, group, learning organisation, society, and person, depending on specific attributes, such as their physical location or period (Fondon, 2017). Although the values of diversity are inclusive, numerous enterprises and individuals continue to struggle with fairness, promotion, equity, and diversity questions (Fondon, 2017). Sherbin and Rashid (2017) argue that in workplaces where variety equals likeness without incorporation of differences, such businesses will not entice global multitalented employees that inspire, contribute, innovate and evolve the business. Clark (2015) argues that diversity inclusiveness allows employees to feel engaged, involved, treated fairly and equally, and as such, they are inclined to become stronger players in business strategy achievement. Furthermore, they are less likely to leave their institutions for jobs with competitors.

Effective diversity values improve managerial effectiveness, largely by decreasing conflict amongst the participants in the group when managers allow complementary thoughts and ideas to flourish. Poor diversity management programs and systems without inclusivity values are ineffective as workers cannot attain and reach their ideal work potential (Joubert, 2017). In any AA transformation process, top leaders must take up the role of chief architect (Kavanagh, 2006). However, poorly prepared leaders can badly affect the self-worth of employees, which can lead to a cessation amongst their groups and create a detrimental work atmosphere where workers feel misunderstood and undervalued (Jaquez, 2016). Joubert (2017) further states that incapacity to achieve labour force multiplicity and diversity may result in a reduction in production and innovation. In terms of gender parity, despite the growing diversity amongst executives, there is a sluggish movement when it comes to growing women taking up top management and leadership positions in both the private and public sectors (Eagly and Chin, 2010).

There is growing unhappiness with the slow rate of genuine transformation in South Africa, with AA, with women representation in leadership positions, and with economic power still being in the hands of White capitalists (Hills, 2014). Gender, racial, skills, educational, and other disparities are still visible in most communities, workplaces, and industrial sectors despite gender equality legislation. In corporate South Africa, the feminine value system that is creative, inclusive, and collaborative is lacking and female managers are few in the top positions in government or medium and large businesses (Cheung and Halpen, 2010; Hills, 2014). This will also apply in the financial services sector. According to Shen, Chanda, D' Netto, and Monga (2009) at a strategic level, what is essential is a leadership attitude that understands that diversity integration, multiplicity, and transcendental leadership with strong values are critical for operational achievement. Senior leaders and managers must provide a commitment to multiplicity leadership values and these should be visible in the business vision, mission, and corporate strategy. Furthermore, leaders and managers must be empowered to eradicate mental and operative obstructions to the handling of diversity integration, transformational objectives, and recruitment of global talent (Shen et al., 2009).

Transformational Leadership in South African financial services

According to the SAHRC (2018) study, the B-BBEE Act describes Black economic empowerment or BEE as the most feasible financial strategy for the enablement of all PDIs. More specifically females, Black employees, youth, people with incapacities, and rural citizens are to be provided with empowerment opportunities through a wide range of combined social and economic initiatives. The BBBEE legislation presents a strategy for transformational leadership towards the redress of past historical imbalances and injustices in employment equity. The domain of financial management and proprietorship arrangements are predominant in the SA transformational regulations such as the B-BBEE act (SAHRC, 2018). Significantly, the same study reveals that to date, B-BBEE initiatives and schemes have been ineffective in fundamentally changing leadership and proprietorship arrangements of big companies (SAHRC, 2018). The B-BBEE act has also been condemned for profiting a small segment of the Black population, nicknamed The Black Elite; while the ordinary Black citizen has thus far been overlooked from B-BBEE benefits (Archibong and Adejumo, 2013). Furthermore, B-BBEE is blamed for the alleged mass exodus of SA citizens who are skilled and qualified to economically sound countries. Individuals with high levels of skill migrate to other nations due to the challenges of gaining equitable jobs, market-related salaries, progressive career paths, and career development opportunities. B-BBEE seems to ignore citizens with high levels of ability and talent, leading to the danger of celebrating short-term transformational goals while neglecting the long-term brain drain (Oosthuizen and Naidoo, 2010).

Could the brain drain be the reason why the SA Department of Trade and Industry (2007) identified a low participation rate of black Africans in middle and top management positions in the banking industry? They raised alarms that lack of financial leadership presented severe challenges to the sector and country. The financial industry in the country is controlled by 4 major banks, named the "Big 4", who jointly hire 131 404 individuals (Mayiya et al., 2019). The Big 4 repeat their promise to support national transformational change, setting targets in the financial industry as well as establishing the Financial Sector Charter (Mayiya et al., 2019). The banks set a goal of 25% black proprietorship by 2010 and an additional 33% of the participants of a firm's board were obligated to be Black (Ward and Muller, 2010). The banking charter stipulated these six key areas of economic empowerment which were to be monitored in terms of a scorecard by the financial institutions themselves, namely: business ownership and control; recruiting and development of human resources; procurement and enterprise development; access to financial services; empowerment financing; and corporate social investment (Ward and Muller, 2010). The financial charter, which dedicated the banking industry to the government enacted strategy of B-BBEE, can be regarded as a significant landmark in redressing the past imbalances of South Africa (Moyo and Rohan, 2006).

The banking sector transformed itself into a leading lending giant for PDIs post-1994; as before democracy proper monetary facilities were unavailable to millions of Blacks in South Africa (Moyo and Rohan, 2006). Yet banks have been criticised for granting Black empowerment banking loans for only a few. This was announced in July 2004 by a leading bank and its insurance subsidiary, in which both would sell 10% of their companies for a joint total of R5.6 billion (Moyo and Rohan, 2006). The deal reserved 40% of shares for Black management and staff, 20% for community groups, and two politically connected individuals received the remaining 40% without collateral. Each of these individual shareholders netted around R200 million (Moyo and Rohan, 2006).

Change in the South African labour market, private sector, and especially in the financial industry has been a relevant subject for several years; and notwithstanding the best exertions by lawmakers and business relations, the pace of change has stayed agonisingly slow (SAHRC, 2018). Furthermore, the fact that White males still control the most profitable businesses in the economy further proves the failure of B-BBEE as singular mechanisms designed to transform the economic sector of the country (SAHRC, 2018). Moreover, the country's Department of Labour initiatives, opportunities, and prospects for advancements are often given to applicants other than black Africans. According to the Department of Labour (2017) report, the financial services industry has seen a rise in Africans, Indian/ Asian, and Coloured persons at entry and middle managerial positions; however, as per the transformation legislation, few Blacks are appointed at senior and executive positions in the financial sector of SA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

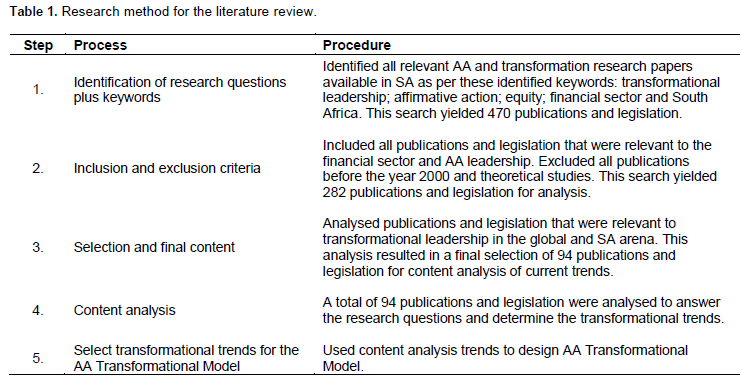

The research method employed was qualitative content analysis (Fanelli et al., 2020; Pratici and Singer, 2021). Qualitative content analysis is defined as a research technique that allows for the subjective interpretation of the content of data through the logical categorisation procedure of coding and classifying themes or patterns (Shava et al., 2021). Qualitative content analysis allows scientists to comprehend social reality in a personal but systematic way (Shava et al., 2021). Superior research studies usually integrate both qualitative and quantitative analysis of texts and blending of approaches, usually recognised as an efficient method to ensure the dependability of the research in terms of soundness and trustworthiness (Sándorová, 2014). The aim of using content analysis as a research technique is to deliver new awareness and more understanding of a particular occurrence, to acquire a better and more concise explanation of the phenomenon, as well as to define and measure a phenomenon (Moldavska and Welo, 2017). The method for extracting relevant data for analysis as findings consist of these 5 steps: Identification of research questions plus keywords; Inclusion and exclusion criteria; Selection of final content; content analysis; selection of transformational trends for the proposed AA transformational model for the SA financial sector. Table 1 presents the research method for the literature review.

RESULTS

Literature evidence reveals that in response to research question 1 of this paper, although the SA government introduced numerous laws to address transformation in the country, the slow pace of AA transformation points to the government's inability to enforce the EE legislation. Furthermore, most of the senior management in the private sector consists of White males; the assumption is that there is a reluctance to replace themselves with equally competent and qualified Black colleagues. In response to research question 2 of this paper, while though numerous research papers report on the panaches of leadership, characters, and executive leadership influences on business results; there is limited research on how leadership influences transformation and affirmative action (Raghu, 2018). Ng and Sears (2012) found that while transactional leaders achieve operative or mechanical justice and comply with AA laws to avoid penalties; they are reluctant to initiate and sustain AA strategies that effectively promote transformation. Transformational leaders employ multiplicity management strategies, hence they are more inclined to meet AA targets and goals (Ashikali and Groenewald, 2015; Kunnanatt, 2016). Raghu (2018) found that although transformational leaders may be more armed at inspiring and stimulating their supporters to use their ethical duty when it comes to applying obedience to laws such as affirmative action, transcendental leadership styles may work better if legislation is implemented and monitored effectively. In contrast, Ashikali and Groenewald (2015) argue that businesses could benefit from managing diversity policies by adopting a transformational management style. Transformational and transcendental leaders are inclined to be more involved with collective fairness and they feel encouraged to achieve diversity since it is ethically the correct thing to do (Ng and Sears, 2012; Basu, 2015). These findings are highly significant and indicate that multiplicity leadership styles do indeed promote affirmative action if the intention and motivation exist.

In response to research question 3 of this paper, SA financial services leaders and managers do, yet neglect to promote affirmative action. While in 2004, the Big 4 banks in SA voluntarily established the Financial Sector Charter to transform the banking industry, they achieved very little with regards to effective AA transformation (Mayiya et al., 2019). The financial industry of SA has the best strategies for AA target achievement theoretically; yet practically, they fail to execute transformation in most banks. The pace of change has remained agonisingly slow with little representation of the majority racial group in top management, especially in the financial organisations (SAHRC, 2018; SABPP, 2012; Kunnanatt, 2016). Furthermore, there is a very low commitment by leaders and managers to implement transformative and empowering affirmative action (Basu, 2015; Kunnanatt, 2016). Moreover, the private sector in SA pays lip service to transformational legislation and targets (Kunnanatt, 2016; SABPP, 2017). The SA government needs to work collaboratively yet firmly with the financial sector organisations if they are to strategically implement existing AA and transformational legislation in all industrial sectors of the country.

The intensive literature analysis resulted in these six conclusions:

1. Despite legislation such as the Constitution, the Employment Equity Act, and the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Act, discrimination in the workplace continues and the implementation of these laws has not been effective.

2. The pace of change is slow due to the lack of commitment of top leaders and managers in the private sector and the lack of enforcement by the government.

3. Transactional leaders follow AA compliance as per the legislation; however, once they have met their targets, they are not prepared to do anything more than what the law prescribes.

4. Transformational leaders motivate and encourage their supporters and use their virtuous obligation to achieve transformation with laws such as affirmative action.

5. Transcendental leaders may be more effective in promoting and implementing AA legislation as they employ spiritual multiplicity in their strategies.

6. Although the Big 4 banks in SA set up the financial charter in 2004 to transform the banking sector, its implementation has not proved to be successful.

DISCUSSION

Literature suggests that effective transformation, change, and diversity in the South African marketplace, specifically in the corporate world, and particularly in the financial industry is a contentious subject. This is since, despite AA transformational efforts by government and policy makers, the rate of change has stayed agonisingly sluggish in all industry sectors. As mandated or recom-mended by SA legislation on AA and transformation, most industrial sectors initiated radical shifts and changes. The country's financial industry initiated a charter that stipulated targeted efforts towards meeting AA transformation and EE transformation goals. It is significant to note that some financial organisations sur-passed employment equity goals, promoting Blacks into junior and middle managerial ranks. More significantly, it is noted that while an improvement in AA occurs at the middle managerial level, the same cannot be stated for senior and executive managerial positions (Mayiya et al., 2019).

The citizens of democratic South Africa imagined a fresh start that was demonstrated by a governmental instituted transformative plan, with AA, EE, and BBBEEE as the integrated strategy (Rotich et al., 2015). After more than 20 years since the implementation of AA laws, progress has been very slow. Some experts have projected that it will take until 2060 to achieve equitable population representation in top and executive manage-ment positions in SA (SABPP, 2012). Low dedication to AA from senior leadership, as supported by leadership who pay lip service to the need for transformation in the country's workforce presents high transformational risks (SABPP, 2017). The 2016/2017 Employment Equity report statement reveals the following significant statistics worth noting:

1. SA Blacks comprise approximately 78% of the economically active population, yet they occupy only 14.4% of the top and executive positions in the workforce.

2. SA Whites comprise approximately 12% of the population, yet they hold 68.5% of the highest leadership occupations (October, 2017).

Grant (2007) argues that in South Africa a tiny but influential White minority has dominated all financial and workforce action including labour intensive work. SA workforce leaders are tasked to transform the country's workplace and workforce to be more illustrative of all population groups in all occupational categories. While legislation has transformative goals, to the detriment of inclusive transformation and socioeconomic justice, White leaders and managers continue to act as caretakers for most of the Black population. Black people may be in control constitutionally but they are not in power economically (Rotich et al., 2015; SABPP, 2017).

Different existent theories reveal a lack of progress in implementing changes in the SA financial sector about transformation especially AA transformation. This paper adds to the body of knowledge on affirmative action, transformation, employment equity, management, and leadership within the South African context. The paper highlighted how the SA legislation, leadership styles, and financial organisations promoted AA and transformation for the country. Imbalances in workforce planning and misrepresentation of the population groups within organisations hinder the growth of the South African economy. The theoretical knowledge on the strategic implementation of affirmative action and transformation in the South African banking sector will contribute to more equitable workplace opportunities, an authentically representative economy, and create socially just organisational strategies, policies and practices.

The insights gained into the implementation and value of affirmative action for the country, continent, and world economies and societies are expected to contribute practically. Leaders, managers, and the South African financial services can benefit from implementing AA and transformational legislation as follows:

1. Diversity integration of the workplace can remove past biases and stereotypes.

2. Effective and efficient implementation of employment equity strategies and AA legislation in organisations will result in a productively diverse labour force.

3. A productive diverse workforce will reinforce social upliftment and promote innovation in businesses.

4. Management that represents the population authen-tically tends to influence work performance, attendance, retention, improved customer service, and client gratification (SABPP, 2017).

5. Diverse and inclusive management structures reveal improved innovation, creativeness, engagement, productivity, proficiency, and the company image is heightened (SABPP, 2017).

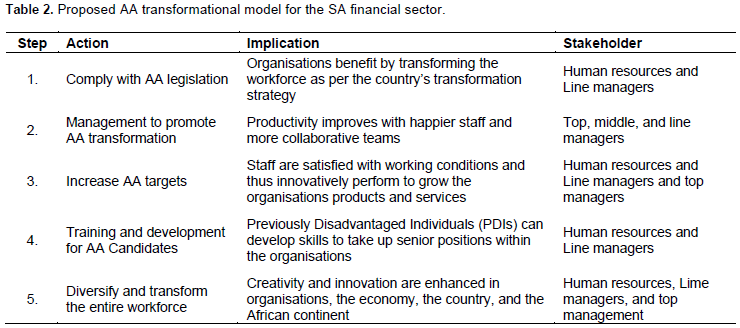

The practical contribution of this paper is the proposed AA Transformational Model for the SA Financial Sector, as presented in Table 2. The model consists of five action steps that the key stakeholders in the organisations must take to ensure the successful implementation of AA. These five actions should be implemented as follows: Comply with AA legislation; Management to promote AA transformation; Increase AA targets; Training and development for AA candidates; Diversify and transform the entire workforce.

The proposed model is designed to assist organisations in both the private sector and public sector with strategies to effectively transform their organisations. Each step in the transformational process model is discussed further.

Step 1: Comply with AA legislation

The purpose of the EEA is to promote fair labour practices and social justice in the SA workplace (Department of Labour, 2014). Organisations that implement AA legislation will be able to achieve their Employment Equity targets and help transform the workplace in South Africa. Organisations should develop AA strategies which must be submitted annually to the Department of Labour. There should be consultation with the unions and employees to obtain agreement regarding the plan, examine their employment procedures, practices and strategies to ensure that they have the support of employees (Department of Labour, 2014). The consultation process is vital to make sure that the aim of AA is realised in the organisation.

Step 2: Management to promote AA transformation

There should be a commitment to the implementation of AA from all levels of management within the organisation, commencing at the top in the decision-making levels to ensure senior management agreement to the AA process (Booysen, 2007). The EEA requires employers to implement AA measures to accelerate transformation for Previously Disadvantaged Individuals (PDIs).

Step 3: Increase AA targets

The aim of the EEA is not just to meet targets but to ensure that past practices of discrimination in the work-place are eliminated and to ensure that all racial groups are fairly presented at all occupational levels within organisations. The organisation should provide the necessary training and development to employees that will enable them to take up better positions in the organisation when they occur. This will result in a more satisfied and happier workforce.

Step 4: Training and development for AA candidates

Without adequate skills development in the workplace AA will fail, and this will result in dissatisfaction and lowering of standards (Martha, 2010). It is specified in the EEA that suitably qualified individuals should be identified for training and development (Martha, 2010). The organi-sation should link its training and development initiatives to succession planning to ensure that employees receive enough training and mentoring to prepare them for future promotion (Van Der Heyden, 2013).

Step 5: Diversify and transform the entire workforce

One of the main objectives of the EEA is to achieve a diverse workforce that is broadly representative of the SA population. The CEO should provide robust guidance and champion the advantages of diversity and should take a strong position on supporting the need for and the benefits of a diverse workforce (Wambui et al., 2013). The organisation should generate and uphold a constructive work environment where the similarities and differences of employees are valued, so all can attain their full potential and exploit their strengths to the company’s intended aims and purposes (Wambui et al., 2013).

CONCLUSION

After 26 years of democracy, and the commemoration of 24 years of the South African Constitution, it is the ideal time to establish the level of transformational progress in the country, especially in the financial sector. Theoretical research was conducted to determine whether AA transformation is legislatively complied with, what leadership styles promote AA transformation, and how South African financial services managers can promote AA transformation strategically. Theoretically, this paper added to the body of knowledge on workforce transformation. Practically, this paper presents the AA Transformational Model for SA Financial Sector managers to implement AA transformation positively. Further qualitative and quantitative research is recommended to explore and examine whether SA managers can accelerate AA transformation, especially in the financial sector, and especially through training and development.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors have not declared any conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

|

Aigbavboa C, Oke AE, Mokasha MD (2016). Implementation of the skills development act in the South African construction industry. The Scientific Journal for Theory and Practice of Socio-Economic Development 5(9):53-64. |

|

|

Alexander N (2006). Affirmative action and the perpetuation of racial identities in post-apartheid South Africa. Lecture originally delivered the University of Fort Hare. The University of Fort Hare. |

|

|

Archibong U, Adejumo O (2013). Affirmative action in South Africa: Are we creating new casualties? Journal of Psychological Issues in Organizational Culture 3(1):14-27. |

|

|

Ashikali T, Groeneveld S (2015). Diversity management in public organisations and its effect on employees' affective commitment: The role of transformational leadership and the inclusiveness of the organisational culture. Review of Public Personnel Administration 36(2):146-168. |

|

|

Basu KK (2015). The leader's role in managing change: Five cases of technology?enabled business transformation. Global Business and Organizational Excellence 34(3):28-42. |

|

|

Bock Z, Hunt S (2015). 'It's just taking our souls back': Discourses of apartheid and race. South African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 33(2):141-158. |

|

|

Booysen L (2007). Barriers to employment equity implementation and retention of blacks in management in South Africa. Journal of Labour Relations 31(1):41-71. |

|

|

Booysen LAE, Nkomo SM (2010). Employment equity and diversity management in South Africa. In International handbook on diversity management at work: Country perspectives on diversity and equal treatment. (Ed), Klarsfeld. pp. 218-243. |

|

|

Chabane N, Goldstein A, Roberts S (2006). The changing face and strategies of big business in South Africa: More than a decade of policy democracy. Industrial and Corporate Change 15(3):549-577. |

|

|

Cheung FM, Halpern D (2010). Women at the top: powerful leaders define success as work + family in a culture of gender. American Psychologist 65(3):182-193. |

|

|

Chao CC (2017). The Chinese female leadership styles from the perspective of the trait and transformational theories. China Media Research 13(1):63-73. |

|

|

Clark PM (2015). Diversity and inclusion is an agency imperative. Public Manager 44(2):42. |

|

|

Coomey P (2007). South Africa to BEE or not to BEE: After 13 years of ANC rule, the question still persists on how far the government has economically empowered black South Africans. New African 31-32. |

|

|

Coomey P (2007). South Africa to BEE or not to BEE. New African, August/September, 2007. pp. 30-32. |

|

|

Crossan M, Mazutis D (2008). Transcendent leadership. Business Horizons 51(2):131-139. |

|

|

Curtis GJ, Cerni T (2015). For leaders to be transformational, they must think imaginatively. Journal of Leadership Studies 9(3):45-47. |

|

|

Department of labour (2014). Commission of Employment Equity: Annual report 2013-2014. Available at: |

|

|

Department of Labour (2015). Commission of employment equity: Annual report 2014-2015. Available at: |

|

|

Department of Labour (2017). Commission for employment equity: Annual report 2016-2017. Available at: |

|

|

Department of Labour. (2019). 19th Commission for employment equity: Annual report 2018-2019. Available at: |

|

|

Department of Trade and Industry (2007). Financial sector Charter on Black Economic Empowerment. Available at: |

|

|

De Vries MK, Korotov K (2010). Developing leaders and leadership development. Available at: |

|

|

Doraiswamy IR (2012). Servant or leader? Who will stand up, please? International Journal of Business and Social Science 3(9):179-182. |

|

|

Eagly AH, Chin JL (2010). Diversity and leadership in a changing world. American Psychologist 65(3):216-224. |

|

|

Fanelli S, Salvatore FP, De Pascale G, Faccilongo N (2020). Insights for the future of health system partnerships in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic literature review. BMC Health Services Research 20(1):1-13. |

|

|

Fondon J (2017). Moving beyond diversity to inclusion. BusinessWest Staff. |

|

|

Galinsky AD, Todd AR, Homan AC, Phillips KW, Apfelbaum EP, Sasaki SJ, Richeson JA, Olayon JB, Maddux WW (2015). Maximizing the gains and minimizing the pains of diversity: A policy perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Sciences 10(6):742-748. |

|

|

Gardiner JJZ (2011). Transcendent leadership: Pathway to global sustainability. Paper presented at the first Working Collaboratively for Sustainability International Conference, Seattle University, Seattle, Washington. |

|

|

Gning TK, Yazdanifard R (2015). The general review of how different leadership styles cause the transformational change efforts to be successful. International Journal of Management, Accounting and Economics 2(9):1130-1140. |

|

|

Grant T (2007). Transformation challenges in the South African workplace: A conversation with Melissa Steyn of Incudisa. Business Communication Quarterly 70(1):14-19. |

|

|

Havenga W, Mehana V, Visagie JC (2011). Developing a national cadre of effective leadership towards sustainable quality service delivery in South Africa. African Journal of Business Management 5(31):12271-12282. |

|

|

Herring C (2009). Does diversity pay: Race, gender, and the business case for diversity? American Sociological Review 74(2):208-224. |

|

|

Hills J (2014). Addressing gender quotas in South Africa: Women empowerment and gender equality legislation. Deakin Law Review 20(1):153-184. |

|

|

Hirtz PD, Murray SL, Riordan CA (2007). The effects of leadership on quality. Engineering Management Journal 19(1):2-27. |

|

|

Horwitz FM, Jain H (2011). An assessment of employment equity and broad-based black economic empowerment developments in South Africa. Equality, diversity, and inclusion. An International Journal 30(4):297-317. |

|

|

Ifeacho C, Ngalawa H (2014). Performance of the South African banking sector since 1994. Journal of Applied Business Research 30(4):1183-1195. |

|

|

Isebor JE (2018). Transcendental leadership for 21st century: A narrative inquiry on effective leadership and workplace spirituality. (Doctoral dissertation, School of Advanced Studies, University of Phoenix). |

|

|

James S (2009). The skills training levy in South Africa: Skilling the workforce: Skilling the workforce or just another tax? SKOPE, Issue Paper 19, University of Oxford. |

|

|

Jaquez F (2016). The global leadership: Trifecta. Global HRD. |

|

|

Joubert YT (2017). Workplace diversity in South Africa: Its qualities and management. Journal of Psychology in Africa 27(4):367-371. |

|

|

Katiyatiya LM (2014). Substantive equality, affirmative action and the alleviation of poverty in South Africa: A socio-legal enquiry (Doctoral dissertation, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa). |

|

|

Kavanagh MH (2006). The impact of leadership and change management strategy on organizational culture and individual acceptance of change a merger. British Journal of Management 17(1):83-103. |

|

|

Kishore K, Nair A (2013). Transcendental leaders are the moral fiber of an organization. Journal of Business Management and Social Sciences Research 2(7):57-62. |

|

|

Kotze JS (2012). Non-racialism, nation-building, and democratic consolidation in South Africa. Politeia 31(2):89-108. |

|

|

Kundu SC, Bansal J, Chawla AS (2015). Managing workforce diversity through HR practices: A review. In Kundu SC, Arora U, Ram T, Singh K (eds.), Emerging Horizons in Business Management. Delhi, India: Victorious Publishers. pp. 115-124. |

|

|

Kunnanatt JT (2016). 3D Leadership: Strategic linked leadership framework for managing teams. Economic Management and Financial Markets 11(3):30-50. |

|

|

Lam CS, O'Higgins ERE (2012). Enhancing employee outcomes: The interrelated influences of manager's emotional intelligence and leadership style. Leadership and Organization Development Journal 33(2):149-174. |

|

|

Lee RK (2011). Implementing Grutter's diversity rationale: Diversity and empathy in leadership. Duke Journal of Gender Law and Policy 19:133-178. |

|

|

Lee HA (2016). Affirmative action regime formation in Malaysia and South Africa. Journal of Asian and African Studies 51(5):511-527. |

|

|

Liu CH (2007). Transactional, transformational, transcendental leadership: Motivation effectiveness and measurement of transcendental leadership. University of Southern Los Angeles, California USA. |

|

|

Lolwana P, Ngcwangu S, Jacinto C, Millenaar V, Martin ME (2015. Understanding barriers to accessing skills and employment of youth in Argentina and South Africa: Synthesis report. |

|

|

Long CS, Yong LZ, Chuen TW (2016). Analysis of the relationship between leadership styles and affective organizational commitment. International Journal of Management, Accounting, and Economics 3(10):572-598. |

|

|

Lyndon S, Rawat PS (2015). Effect of leadership on organizational commitment. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations 51(1):97-108. |

|

|

Martha TM (2010). Application of the Employment Equity Act and diversity in the mining industry (Master's thesis). Faculty of Economics and Management Science, North West University, Potchefstroom University. Potchefstroom. |

|

|

Mazibuko JV, Govender KK (2017). Exploring workplace diversity and organisational effectiveness: A South African exploratory case study. SA Journal of Human Resource Management 15(0):1-10. |

|

|

Mayiya S, Schachtebeck C, Diniso C (2019). Barriers to career progression of black middle managers: The South African perspective. ACTA Universitatis Danubius 15(2):133-147. |

|

|

Mbembe A (2008). Passages to freedom: The politics of racial reconciliation in South Africa. Public Culture 20(1):5-18. |

|

|

McCarthy DJ, Puffer SM, Darda SV (2010). Convergence in entrepreneurial leadership style: Evidence from Russia. California Management Review 52(4):48-72. |

|

|

Mehta S, Maheshwari GC, Sharma SK (2014). Role of leadership in leading successful change: An empirical study. The Journal Contemporary Management Research 8(2):1-22. |

|

|

Mishi S, Sibanda K, Tsegaye A (2016). Industry concentration and risk-taking: Evidence from the South African banking sector. African Review of Economics and Finance 8(2):112-135. |

|

|

Moldavska A, Welo T (2017). The concept of sustainable manufacturing and its definitions: A content-analysis based literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production 166:744-755. |

|

|

Moyo T, Rohan S (2006). Corporate citizen in the context of the financial services sector: What lessons from the financial services charter? Journal Developments Southern Africa, 23(2): 289-303. |

|

|

Mummenthey C (2010). Skills development in South Africa. Knowres, Randburg. |

|

|

Nagendra A, Faooqui S (2016). Role of leadership style on organizational performance. International Journal of Research in Commerce and Management 7(4):65-67. |

|

|

Naidoo V, Kongolo M (2004). Has affirmative action reached South African? Journal of International Women's Studies 6(1):124-136. |

|

|

Nair A (2016). Transcendental leadership for a virtuous organization: An Indian approach. International Journal of Recent Advances in Organizational Behaviour and Decision Sciences 2(1):2311-3197. |

|

|

Naji ZA, Lailawati MS, Mohamed ZA, Amini AA (2014). The west and Islam perspective of leadership. International Affairs and Global Strategy 18:42-56. |

|

|

Ng ES, Sears GJ (2012) CEO leadership styles and the implementation of organizational diversity practices: Moderating effects of social values and age. Journal of Business and Psychology 25(2):281-292. |

|

|

October A (2017). The cost of snubbing employment equity. Finweek 8. |

|

|

Odumeru JA, Ifeanyi GA (2013). Transformational vs. transactional leadership theories: Evidence in literature. International Review of Management and Business Research 2(2):355-361. |

|

|

Oosthuizen RM, Naidoo V (2010). Attitudes towards and experience of employment equity. SA Journal of Industrial and Organisational Psychology 36(1):1-9. |

|

|

Op't Hoog C, Siebers H, Linde B (2010). Affirmed identities? The experience of black middle managers dealing with affirmative action and equal opportunity policies at a South African mine. South African Journal of Labour Relations 34(2):60-83. |

|

|

Pratici L, Singer PM (2021). Covid-19 vaccination: What do we expect for the future? A systematic literature review of social science publications in the first year of the pandemic (2020-2021). Sustainability 13(15):8259. |

|

|

Raghu NS (2018). Leadership styles, roles, and attributes that leaders need to influence employment equity (Master's thesis). University of Pretoria, Gordon Institute of Science. |

|

|

Reddy A, Parumasur SB (2014). Affirmative action: Pre-implementation criteria, purpose, and satisfaction with diversity management. Corporate Ownership and Control 12(1):683-691. |

|

|

Rehman RR, Waheed A (2012). Transformational leadership style as a predictor of decision-making styles: Moderating role of emotional intelligence. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences 6(2):257-268. |

|

|

Roman LJ, Mason R (2015). Employment equity in the South African retail sector: Legal versus competence and business imperatives. South African Journal of Labour Relations 39(2):84-104. |

|

|

Rotich R, Ilieva EV, Walunya J (2015). The social formation of post-apartheid South Africa. The Journal of Pan African Studies 8(9):499-512. |

|

|

Ruggieri S, Abbate CS (2013). Leadership style, self-sacrifice, and team identification. Social Behavior and Personality 41(7):1171-1178. |

|

|

SA Board for People Practices (2012). SABPP position paper on employment equity and transformation. |

|

|

SA Board for People Practices (SABPP) (2017). Integrating skills development, employment equity, and B-BBEE transformation. |

|

|

Sándorová Z (2014). Content analysis as a research method in investigating the cultural components in foreign language textbooks. Journal of Language and Cultural Education 2(1):95-128. |

|

|

South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) (2016). National hearing on unfair discrimination in the workplace. |

|

|

Shava GN, Heystek J, Chasara T (2021). Instructional Leadership: Its Role in Sustaining School Improvement in South African Schools. International Journal of Social Learning 1(2):117-134. |

|

|

Shen J, Chanda A, D' Netto B, Monga M (2009). Managing diversity through human resource management: An international perspective and conceptual framework. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 20(2):235-251. |

|

|

Sherbin L, Rashid R (2017). Diversity doesn't stick without inclusion. Available at: |

|

|

Simatele M (2015). Market structure and competition in the South African Banking sector. Procedia Economics and Finance 30:825:835. |

|

|

Southall R (2014). The black middle class and democracy in South Africa. Journal of Modern African Studies 52(4):647-670. |

|

|

Sturm R, Vera D (2011). Towards an expanded model of transcendent leadership: Substitutes and the societal level. Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceedings 1:1-6. |

|

|

Stebbins G (2017). Six Keys to transcendent leadership. Forbes. Available at: |

|

|

Sudha KS, Shahnawaz MG, Farhat A (2016). Leadership styles, leader's effectiveness, and well-being: Exploring collective efficacy as a mediator. Vision 20(2):111-120. |

|

|

Swierczek FW (2014). Transcendental leadership in the great world disorder. Asian Institute of technology Vietnam. Available at: |

|

|

Tabassum N, Nayak BS (2021). Gender stereotypes and their impact on women's career progressions from a managerial perspective. Indian Institute of Management Kozhikode Society and Management Review 10(9):1-17. |

|

|

Umme SS, Mohd RD, Lui Y (2015). Transactional or transformational leadership: Which works best for now? Available at: |

|

|

Validova AF, Pulaj E (2016). Leadership styles in transitional economies. Academy of Strategic Leadership Management Journal 15:1-7. |

|

|

Van Der Heyden CC (2013). Employee's perception of employment equity fairness within a mining organisation in South Africa. (Master's thesis). Department of Industrial Psychology, University of Western Cape, Cape Town. |

|

|

Visagie C, Linde H (2010). Evolving role and nature of workplace leaders and diversity: A theoretical and empirical approach. Managing Global Transitions 8(4):381-403. |

|

|

Wambui TW, Wangombe JG, Muthura MW, Kamau AW, Jackson SM (2013). Managing workplace diversity: A Kenyan perspective. International Journal of Business and Social Science 4(16):199-218. |

|

|

Ward M, Muller C (2010). The long-term share price reaction to back economic empowerment announcements on the JSE. Investment Analysis Journal 39(71):27-36. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0