ABSTRACT

This research studies the impact of microfinance services on the entrepreneurial success of users of such services who are mostly women of the lowest income categories. Three microfinance financial services namely, microcredit, micro-savings and micro-insurance have been identified through literature among other non -financial services. In this study, researcher has studied only the influence of financial services of microfinance on entrepreneurial success of women entrepreneurs. An empirical investigation is carried out among a sample of 464 women receiving microfinance services, selected using stratified random sampling technique. The data were collected using a structured questionnaire through face to face interviews. The statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) (version 21) is employed to test the relationships between these microfinance services and entrepreneurial success. The sample of this study captures only the women entrepreneurs from Non-Bank Financial Institutions (NBFIs) registered with the Central Bank of Sri Lanka. The results have discovered that microcredit and micro-savings have a positive relationship with entrepreneurial success of women, while micro-insurance has not shown such a relationship. These findings can be helpful to the policy makers in developing the microfinance sector and microfinance institutions to design their service offers. The research identifies some important areas for future research as well.

Key words: Microfinance, microfinance services, microfinance institutions, entrepreneurial success.

The existence of microfinance as a means of supporting the poor, dates as far back as eighteenth and nineteenth century. This has been particularly practiced in Asia and in a number of European countries (Seibel, 2005). Even in Latin America and South Asia it has evolved out of experiments since very early history. Hence, microfinance is not a recent development but it became a widely known phenomenon with the success it gained in Bangladesh in 1976 (Aghion and Morduch, 2005).

However, Singh (2009) has recognized microfinance as one of the new development strategies for alleviating poverty by developing social and economic status of the poor, mainly through the empowerment of women. In poor countries, microfinance has been recognized as a means of facilitating sustainable economic development and has become a popular subject among international donor community (Senanayake and Premaratne, 2005).

Further, these authors feel that microfinance has been successfully made use of as a pro-poor developmental strategy in many countries. According to the findings of studies conducted in countries such as Bangladesh, India, China, Kenya, Tanzania, Sri Lanka, and many others, microfinance can be considered as a tool for alleviation of poverty, among low income categories of the society and especially the women (Atapattu, 2009; Cooper, 2014; Grameen Bank, 2012; Kabeer, 2005). Microfinance has been a strategy for many poverty alleviation initiatives (Khandker, 2005) and targeted almost one third of the world population who live on less than $2 a day (Khavul, 2010).

According to UNDP (2012), 1.4 to 1.8 billion in the world lives under the poverty line of which 70% are women. The studies conducted in a number of countries confirm that the majority under the poverty line is women. Many of these micro-enterprises are operated by women, who are poverty stricken disproportionately. The women worldwide in 2013 have registered a poverty rate of 14.5% (NWLC, 2015). According to the Department of Census and Statistics (DCS) of Sri Lanka, population below poverty line in Sri Lanka in 2012/13 was 6.7% with 5.3% below the poverty line according to this survey.

Though, the word “microfinance” literally means small loans, it encompasses a wider set of activities than provision of small loans to the poor. Burton et al. (2008) state that microfinance tries to facilitate a wide section of people to make use of emerging market opportunities by facilitating them with small scale financial services, especially to low income clients. These clients are naturally barred from access to formal banking services.

Littlefield and Rosenberg (2004) on the same subject, conclude that the microfinance institutions (MFIs) have undertaken to fulfill the market needs of the economically active low income people who generally do not belong to the formal financial sector.

By bridging this gap in the market in a financially sustainable manner, MFIs have become part of the formal financial system of their respective countries. In addressing this gap in Sri Lanka, there are a wide range of organizations from small private operators, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and Non- Bank Financial Institutes (NBFIs) registered with the Monetary Board of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka and operate as MFIs on a commercially viable basis.

Services of MFIs encompass financial services such as provision of loans, offering products and facilities for savings, insurance policies, money transfers and payments among many others. The practitioners and researchers have different viewpoints on the range of services and target recipients of microfinance. These financial services are offered to lower income clients, generally communities, with the object of supporting economic development through the growth of entrepreneurial activity (Bruton et al., 2011; Khavul et al., 2013).

According to the Census and Statistics Department of Sri Lanka (CSD) in 2013, the women account for 51.8% of the population in Sri Lanka. The majority of these women belong to low income category and 14.5% are below the poverty line. Sixty nine percentage of the ‘economically inactive population’ are females, and account for only 31.6% of the ‘economically active population’ (labour force) (Department of Census and Statistics-Sri Lanka, 2014).

This implies that there is a large untapped female population in the country, which could be utilized for development of the country, by facilitating them to become entrepreneurs. Given the fact that majority of the population is women in Sri Lanka and attracting them to the labour force is of utmost importance. The microfinance services are offered mainly to women by the microfinance institutions in Sri Lanka like in many other countries. Hence, evaluating the influence of microfinance services in achieving entrepreneurial success of women is vital especially in the context of having diverse views on the outcome.

Hence, it is seen from the aforementioned literature that microfinance attempts to achieve its, development objectives by providing microfinance services pre-dominantly, to women through developing their entre-preneurial activity. Therefore, studying the relationship between microfinance services and entrepreneurial success of women is fully justified as it will throw light on relative importance of each of these microfinance services. Though, there are many research studies conducted on the overall impact of microfinance with respect to poverty and development, there appears to be lack of such studies on specific services of microfinance except micro-credit and their impact on entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial success.

Hence this study attempts to address this gap. The services of microfinance can be clearly categorized into two areas, namely, financial and non-financial and this study is limited only to the impact of financial services on the entrepreneurial success of poor women.

The key feature of micro financing is that lending is to the poor who do not have access to financial resources to setup enterprises, and enforcing the recovery collectively on clusters and groups of such borrowers (Kirru, 2007) which is known as “Joint Liability Lending” (JLL) in microfinance sector, targeted to the poor in society who cannot borrow individually, but borrow within a group of other borrowers (Kirru, 2007).

These borrowers of joint liability lending organized into groups act as security for each other. Therefore, the group, not the individual, is responsible for loan settlement to the MFIs. The key characteristics of this model are pressure and monitoring by the peers especially on the settlement of loans obtained by individual members. This study focuses on the JLL model.

These financial services are now being extensively offered by the MFIs to women entrepreneurs of the microfinance sector in Sri Lanka. These MFIs belong to public, private or non-governmental sectors operating in rural as well as urban areas mainly representing low income communities. The main object of microfinance services is to facilitate the poor to improve their financial position, allowing them to make use of business opportunities and facilitate the growth of their enterprises.

Asian Development Bank (2012) report highlights that over 900 million people in about 180 million households live in poverty; in the Asian and Pacific region alone. According to Sharma (2001), more than 670 million of these poor people belong to rural sector and rely on secondary occupations as well, as their growing needs cannot be satisfied through income from agriculture alone. These secondary occupations include paid employment, from micro enterprises over services such as carpentry and weaving to self-employed enterprises in food, tailoring and shoe repairing (Robinson, 2001).

The literature on microfinance confirms that it is conceptually unique everywhere in the world. However, due to variations in the environments and implementation results of microfinance programs could be diverse, hence a programme which is successful in a certain country should not necessarily be equally successful in another country (De Silva et al., 2006). Accordingly, “Grameen” concept introduced by Muhammad Yunus in Bangladesh (1976) may not necessarily be successful in Sri Lanka or in any other country due to socio economic differences in these countries and ground realities.

Setting MFIs to service the financial needs of the poor is somewhat recent. Even the institutions dealing with development finance did not pay attention to serve poor segments of the society since the cessation of the Second World War into the 1970s. This point of view changed as those who concerned experienced that large amounts of foreign trade invested in big projects did not necessarily result in the "trickledown effect” which had been expected (Robinson, 2001). The Bangladesh Rural Action Committee (BRAC), a biggest MFIs in the world, was one of the first organizations which excluded that poor households from the formal banking system for lack of collateral (Feroze, 2002).

However, novel approaches to financing the poor, that reduced the riskiness and costs of making small, un-collateralized and cheap loans were introduced with the development of micro-finance movement. The criticism on these financing schemes was the high operating cost for donors and in certain cases, for the borrowers as well, due to high transaction costs.

Further, these service providers have failed to reach many potential customers. According to Littlefield et al. (2003), the coverage of services of microfinance, and its’ impact has gone beyond just business loans. The poor, use these financial services especially loans, for their health and education needs and meet a wide variety of other cash needs they encounter in addition to business investment in their micro enterprises. The focus of many microfinance programmes is on women as the recipients of microfinance services who are generally poor, this helps in bringing down the gender disparity to a certain extent.

In addition to empowering women, this approach has helped in better repayment performance as women appear more responsible. Further, women are more likely to invest increased income in the household and family well-being (Littlefield et al., 2003). Hence, microfinance not only acts as an economic stimulator for small enterprises but also impacts on their social wellbeing.

In reviewing the literature, it appears that the nature of microfinance is complex and in practice often not understood clearly and problems arise between parties with conflict of interest, involved in the process. The inadequacy of knowledge on the potential clients and the modus operandi of these programmes, have resulted in not considering many factors in launching such programmes in their preparatory assistance phases (PAPs). The mobilization of the credit for the poor who have no access to it has been left out of the whole set up. Therefore it is important to design and implement programmes by understanding and giving due consideration to economic, social and political dimensions of role players and stakeholders.

The beginning of microfinance movement in Sri Lanka dates back to 1906, during the British Colonial administration, with the establishment of Thrift and Credit Co-operative Societies (TCCS) under the Co-operative Societies Ordinance of Sri Lanka. In late 1980, a programme known as “Janasaviya” (meaning, strength of the people) was introduced by the Government of Sri Lanka with the objective of alleviating poverty. The interest for microfinance in Sri Lanka has increased considerably since early 1980s, mainly due to the success stories of microfinance experienced by our neighboring countries in the region, especially from Bangladesh and India. However, it was in 1990s microfinance really took off the ground in Sri Lanka, with the introduction of microfinance services to low income economically active people by non-governmental, public and private organizations.

Sri Lanka has a wide range of diverse institutions in microfinance sector and these do not fall under administration of any government or non-government authority. Resulting from this, there is no up-to-date database on these institutions currently available. In this respect, the countrywide survey of MFIs in Sri Lanka commissioned by German Technical Co-operation through a programme titled ‘Promotion of Microfinance Sector’ (GTZ-ProMiS) during the programme phase September, 2005 to November, 2009, is useful as a source of information on the sector. The survey studied various institutions failing into different categories, from the Village Banks, Cooperative Rural Banks and Thrift and Credit Cooperatives to the Regional Development Banks and other institutions from the ‘formal’ financial sector who have ventured into microfinance. The survey also covered the rapidly growing NGO-MFIs some of which have grown very rapidly in the past decade (GTZ-ProMiS, 2005 to 2009).

The survey reveals that the outreach of microfinance services in Sri Lanka is considerable, especially so with regard to savings and deposit products, despite the access to credit remains below its potential and barriers still exist for the lower income groups. Further, the market seems to be characterized by traditional financial products (savings, loans) with few products and services beyond these (for example; insurance, money transfer services). The growth of the sector is hampered by the lack of a coherent regulatory and supervisory framework, governance issues, lack of technology and issues related to the availability of suitable human resources.

Microfinance

The 'microfinance' refers to small scale financial as well as non-financial services, primarily credit and savings for low income clients who are to the economically active to facilitate their involvement in micro-enterprises. In addition, to credit and savings, some micro-finance institutions (MFI) provide other financial services such as micro money transfer and micro insurance and also get involved in social intermediation such as development of social capital and external support services (Aheeyar, 2007). The unique features of microfinance are, small size of the loan not based on collateral, group guarantee, compulsory and voluntary savings, informal appraisal of borrowers and investments and access to repeat and bigger loans based on repayment performances.

Microfinance services

According to Robinson (2001), with the growth of micro-finance sector, attention changed from just provision of financial services to other non-financial services.

Steinwand and Bartocha (2008) state that microfinance is a multifaceted service package that facilitates women to rebuild their lives, plan their future and that of their families, empower them with self- esteem, integrate into social fabric by enjoying access to social networks and making contributions towards welfare of their families and that of the community.

Though the terms, microfinance and microcredit are used interchangeably, it is important to note that microcredit is one component of microfinance. Microcredit is the extension of small loans to entrepreneurs for developing their businesses, who are too poor to qualify for bank loans.

There is no standard definition for micro-enterprise, however, there is some agreement on the attributes of the micro-enterprises especially in the developing countries such as very small scale, low level of technology, low access to credit, lack of managerial capacity, low level of productivity and income, tendency to operate in the informal sector, few linkages with modem economy and non-compliance with government registration procedures are some such features (ILO, 2002).

The Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL) has defined the micro-enterprise as an enterprise which employs up to five people (Lucok et al., 1995). However, it should be noted that even among the government institutions there is no consensus on this definition. Some institutions use two criteria namely; capital employed and size of the work force to decide the category of an organization.

Littlefield and Rosenberg (2004) state that the poor are generally excluded from the formal financial services sector, as a result to fulfill the gap in the market MFI have emerged. These MFIs have become part of the formal financial system of the country and they can access capital markets to fund their lending portfolios (Otero, 1999).

Entrepreneurial success of women

According to Mosedale (2003), to empower people, they should currently be disempowered, disadvantaged by the way power relations shape their choices, opportunities and well-being. She went on to say that empowerment cannot be bestowed by an external party, but must be claimed by those seeking empowerment through an ongoing process of reflection, analysis and action (Mosedale, 2003). She further goes on to say “women need empowerment as they are constrained by the norms, beliefs, customs and values through which societies differentiate between women and men” (Mosedale, 2003). Many MFIs target primarily, or exclusively, women. This practice is based on the common belief that women invest the loans in productive activities or in improving family welfare more often than men, who are known to consume rather than invest loan funds.

Women achieve entrepreneurial success through setting up new enterprises, expansion and improved performance of existing enterprises and improvement of well-being of their families.

Hypotheses

Microfinance encompasses multifaceted services that affords women to rebuild their lives, plan for their future and that of their children, empower them with self- esteem, integrate into social fabric by enjoying access to social networks and making contributions towards welfare of their families and that of the community (Steinwand and Bartocha, 2008).

Microfinance provides services of both financial and nonfinancial nature, including small business loans to lower income clients, generally communities, with the aim of supporting economic development through the growth of entrepreneurial activity (Bruton et al., 2011; Khavul et al., 2013). These studies highlight the relationship between microfinance services and entrepreneurial success of women.

Further, Microfinance offers financial and non-financial services to economically active low income clients. The financial services include such as credit, savings and insurance to poor people living in both urban and rural settings and are unable to obtain such services from the formal financial sector (Schreiner and Colombet, 2001).

However, there seems to be a gap in determining the relationship between individual services and entrepreneurial success of women except some research findings on the impact of microcredit. Hussain and Mahmood (2012) suggest that according to results derived using a quantitative analysis that income, education and health of households have high correlation with access to microcredit.

Further, microfinance loans have a positive impact on poverty reduction (Hussain and Mahmood, 2012). According to an empirical study conducted by Jalilia et al. (2014), the degree of women entrepreneurship development is affected by microfinance in majority of small and medium enterprises. This study has also confirmed the findings of previous studies (Lumpkin and Dess, 1996; Yang, 2008; Jin and Lee, 2009), that multidimensionality of microfinance and independence effect of innovativeness, pro-activeness and risk taking are distinctly correlated. The microfinance services are offered mainly to women by the microfinance institutions in Sri Lanka like in many other countries.

Hence, evaluating the influence of microfinance services in achieving entrepreneurial success of women is vital especially in the context of having diverse views on the outcome. Further, five different services of microfinance has been identified as micro-credit, micro-savings, micro-insurance, business support and skills development programmes have been identified which were supported by literature (Aheeyar, 2007; Bernard et al. (2015). However, this study limits its’ scope to study only the relationship between the financial services of microfinance and entrepreneurial success of women entrepreneurs using these services.

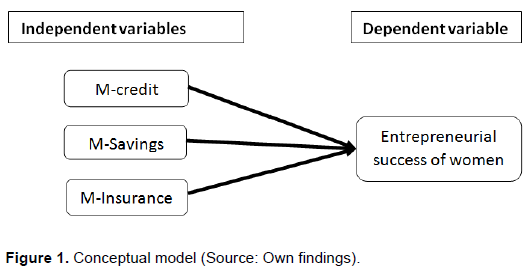

In view of the aforementioned findings, the following conceptual model and research hypotheses have been identified for this study in order to understand the relationship between financial services of microfinance and entrepreneurial success of women (Figure 1).

A study conducted by Roxin (2010) in Sierra Leone confirms that microcredit has a substantial impact on women’s economic empowerment. Kabeer (2005) has found out that access to financial services can and does make important contribution to the economic productivity and social well-being of poor women and their households. However, microcredit operations in India, Bangladesh and Mexico have been criticized for high interest rates and use of microcredit for personal consumption (Roodman, 2012).Therefore, following hypothesis H1 can be developed:

H1: There is a relationship between microcredit and entrepreneurial success of women using microfinance services.

According to studies conducted by Crepon et al. (2010) and Banerjee et al. (2010), a positive impact of microfinance services on business income and profits has been established based on their studies in Morocco and India, while Karlan and Zinman (2011) found that increased access to microfinance in Philippines has resulted in a reduction of the number of businesses run by entrepreneurs and the people employed. Therefore, two following hypotheses can be developed.

H2: There is a relationship between micro- savings and entrepreneurial success of women using microfinance services.

H3: There is a relationship between micro- insurance and entrepreneurial success of women using microfinance services.

Sample and data

A sample of 464 women entrepreneurs receiving microfinance services from NBFI registered with the Central Bank was selected in three districts each of which has majority of Sinhalese, Tamils, and Moors. This was done as there was a strong belief among industry practitioners that the behavior of these entrepreneurs relates to their ethnicity. The women entrepreneurs for collecting data were selected randomly from the NBFI which has the highest membership of such entrepreneurs in each district. The structured questionnaire developed was administered through face-to –face interviews by trained investigators.

Study design

The study makes use of the previous studies, expert opinion and findings of the survey conducted and involve conceptual and empirical analysis. The constructs were identified as presented in section 4. The questions developed for each of the constructs were reviewed by academics and practitioners with relevant expertise in order to maintain clarity and comprehensiveness. The questionnaire was translated into Sinhala and Tamil languages to overcome the language barriers and to improve the comprehension by the respondents (unit of analysis that is, female users of microfinance services). The translated questionnaire was tested for translation errors.

The questionnaire was piloted among 40 female recipients who are receiving microfinance services from NBFIs registered with the Central Bank of Sri Lanka. Using these questionnaires, the reliability and validity were tested and accordingly, some changes to these questions were made. A total of 34 items were included in the final questionnaire with a five point likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 representing strongly disagree to strongly agree.

To analyze the outcome of the study, 5 point Likert scale was used in designing the questionnaire to test the perception of women entrepreneurs’ for agreement or disagreement level on entrepreneurial success, influenced by three variables (microcredit, micro-savings, micro-insurance). The study comprised of two procedures; firstly the assessments of adequacy of measurement items, and second the test of the structural model.

In order to assess the adequacy of the measurement items, individual item reliability, and discriminant validity are measured using SPSS (version 21). Further, using the same computer package, regression analysis is employed to find out model fit and ANOVA to test the hypotheses.

Respondent’s demographic profile

By design, the respondents of the survey were women who make use of microfinance services, according to the age distribution of the sample of respondents, majority (25.6%) were between 30 to 35 years followed by 21.1% in 35 to 40 year range. Sixty percent (60%) of the sample were educated up to G.C.E. (O/L) while the education levels of up to G.C.E. (A/L) and beyond G.C.E. (A/L) were 33.3 and 6.6%, respectively. They also represented an ethnic distribution of 44.5% Sinhalese, 34.5% Tamils and 20.1% Muslims.

Reliability and validity measures

Prior to conducting the survey project, a pilot study was carried out to ensure the reliability and adequacy of measures. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to measure the reliability and internal consistency of the measurement scales.

Accordingly, overall constructs “entrepreneurial success” with 9 items ES1 to ES9 had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.845, however item E7 was dropped as ES7 did not have the required level of inter-item correlation. Similarly, overall construct “micro savings” which has 5 items MS1 to MS5 had a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.720 however, item MS5 was dropped due to its low inter-item correlation value with other items in the construct. In the other three constructs namely: Micro Credit (5), Micro-savings (5), and Micro Insurances had Cronbach’s alpha value over 0.7 and values of inter-correlations with each other items in their respective constructs within the range of 0.3 to 0.7. Hence the reliability and validity of these constructs were sufficient (Nunnally, 1978).

In conducting the main survey, four constructs with a total of 24 items were used. In order to maintain the face/content validity of the scales, experts reviews of literature survey were conducted. Further, the dimensionality of the measurements was assured by performing and exploratory factor analysis following the procedure introduced by Churchill (1979).

Sampling adequacy of the main survey with 464 respondents was confirmed by using the Kaiser-Meyer-Okling (KMO) test which resulted a value of 0.72, since the value is greater than 0.5, the sample fulfilled the requirement of being appropriate for factor analysis.

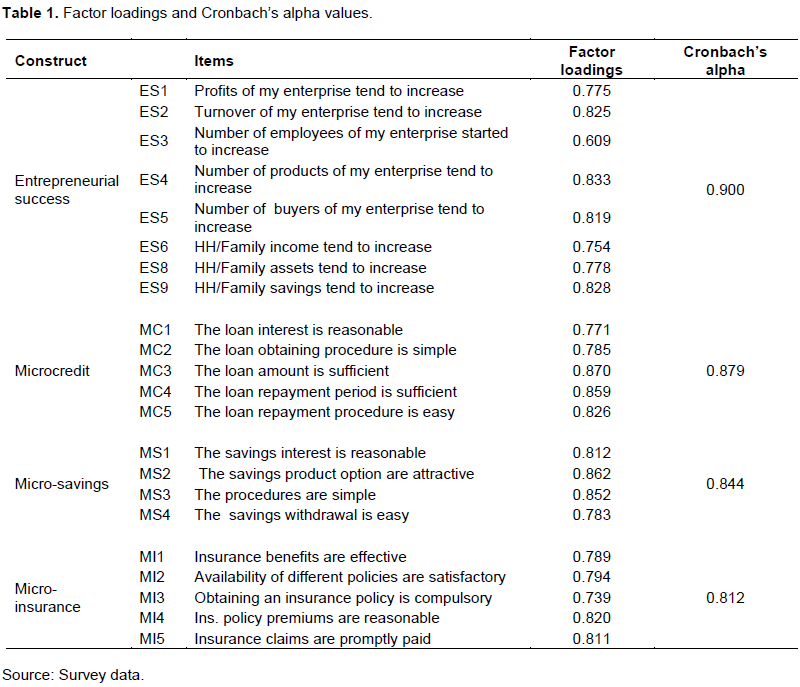

Then, the individual item reliability was assessed by testing the factor loading of each 24 items selected on their respective construct and Cronbach’s alpha to test the reliability of the construct. Table 1 shows the results of reliability of individual item and construct. According to Andrews (1984), factor loadings and Cronbach’s alpha values above 0.7 are acceptable. According to Table 1, all factor loading are more than 0.7 and respective constructs have Cronbach’s alpha value of more than 0.7. Hence, the item selected and constructs have measurement adequacy.

According to Table 2, model summary, value of adjusted R square is 0.492 which indicates that 49.2% of the variation in rating of entrepreneurial success of women is explained by the regression model and ANOVA a that the overall regression result is significant at 0.1% level where the value of F test is 150.675 (sig=0.000). Hence, data is fit to regression model.

According to Table 3, correlations between all the variables are positive and significant at the level of 0.01 (sig=0). The aforementioned analysis shows that H1 and H2 are acceptable at the level of 0.01 (sig=0) significance hence the variable Microfinance and Micro-savings have positive relationships with the dependent variable; Entrepreneurial success. H3 is rejected at the significance level of 0.05 hence Micro insurance has no relationship to Entrepreneurial success.

The main purpose of this empirical study is to understand and discover the significant microfinance service factors influencing entrepreneurial success of women entrepreneurs utilizing such services. Microcredit is the main service factor of microfinance without which other service factors cannot exist, this has lead to the extent of using “microfinance” and microcredit interchangeably by the scholars, though microcredit is only one component of microfinance. According to the findings of the study, microcredit has a positive relationship with entrepreneurial success of women entrepreneurs. This is in line with the findings of past studies. According to Roxin (2010), microcredit has a substantial impact on women’s economic empower-ment. Further, an empirical study conducted among 750 women entrepreneurs supports this view on the relationship between microcredit and entrepreneurial success of women entrepreneurs (GTZ-ProMis, 2005 to2009).

According to the findings, micro-savings has a positive relationship to entrepreneurial success of women entrepreneurs. The findings of previous studies are not very specific on the relationship between these two variables. However, most of the authors are of the view that savings would be useful in fulfilling the funding requirements for expansion of existing enterprises and creation of new enterprises (Newman et al., 2014). Further, a few empirical studies conducted in Sri Lanka support this view (Attapattu, 2009; Ranasinghe, 2008; GTZ-ProMis, 2010).

Though the scholars have identified micro-insurance as one of the factors of microfinance services, the relationship of this variable to entrepreneurial success has not been evident in this study. Accordingly, no relationship has been identified between micro-insurance and entrepreneurial success of women entrepreneurs. The finding of the field survey reveals that micro-insurance is not being provided by most of the NBFIs in Sri Lanka for women entrepreneurs.

Further, these NBFIs have formulated insurance schemes to recover non-payment of loans by the women entrepreneurs in case of a serious eventuality. Hence in the point of view of women entrepreneurs, micro-insurance appear to have not been perceived as useful for entrepreneurial success.

Practical implications

These findings have practical implications for Sri Lankan microfinance institutions in designing their service offers to clients as the findings throw light on the significance of each of these services.

Therefore, specific services with strong significances can be offered in the service mix of MFIs or further developed if such services are currently being offered. In contrast, if there are services which are not significant may be diluted or withdrawn. The policy makers and microfinance operators may use these findings in evaluating the performances of such institutions under their preview.

As per the results explained in section 5, microcredit and micro-savings service dimensions are the ones which have a significant positive impact on the entrepreneurial success of women in microfinance sector in Sri Lanka. Though the emphasis on microcredit is high in the attention given to facilitate micro-savings by the MFIs which appear to be not very effective in the Sri Lankan market hence this service aspect may be improved.

Further, the products/policies offered in micro-insurance are not adequate and do not assist the women entrepreneurs hence it is worth looking at this specific service with a view to developing the sector.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Aghion BA, Morduch J (2005). The economics of microfinance. Cambridge Massachusetts, London, MA: MIT Press.

|

|

|

|

Aheeyar MMM (2007). Impacts of micro finance on micro-enterprises: A comparative analysis of Samurdhi and SEEDS micro enterprises in Sri Lanka, Hector Kobbekaduwa Agrarian Research and Training Institute, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

|

|

|

|

Andrews FM (1984). Construct Validity and error components of survey measures: a structural modeling approach. Public Opin. Quart. 48:409-442.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Atapattu A (2009). State of Microfinance in Sri Lanka. Prepared for Institute of Microfinance, as part of the project on State of Microfinance in SAARC Countries.

|

|

|

|

Asian Development Bank (2012). Finance for the Poor: MF Development Strategy. Manila Development Bank. View

|

|

|

|

Bruton GD, Khavul S, Chavez H (2011). Micro lending in emerging economies: Building a new line of enquiry from the ground up. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 42(5):718-739.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Churchill GA (1979). A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. J. Market. Res. 16(1):64.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Cooper LG (2014). The Impact of Microfinance on Female Entrepreneurs in Tanzania (Senior Thesis). Lake Forest College.

|

|

|

|

Department of Census and Statistics (2014). Household Income and Expenditure Survey, Sri Lanka, 2012/2013.

|

|

|

|

De Silva, Attapattu G, Durant G (2006). .Fitch Ratings, Sri Lanka Special Report GTZ-Pro.Mis program phase Sept. 2009.

|

|

|

|

Feroze A (2002). NGO invasion: Bangladesh a case study, Khalifah Magazine, 30 [online]

|

|

|

|

Grameen Bank (2012), Grameen Bank at a Glance:April 2010 [online]

View

|

|

|

|

Hussain JG, Mahmood S (2012). Impact of Microfinance Loan of Poverty Reduction amongst Female Entrepreneurship in Pakistan. Cambridge Business & Economics Conference. pp. 1-34.

|

|

|

|

International Labour Organization (ILO) (2014). Microfinance for Decent

View

|

|

|

|

Jalilia MF, Mughalb YH, Hussan bin Md Isac A (2014). Effect of Microfinance Services towards Women Entrepreneurs Development in Pakistan. Int. J. Bus. Manage. Econ. Stud. 1(1):37-51.

|

|

|

|

Jin H, Lee M (2009). Characterizations of the Lomax, Exponential and Pareto distributions by conditional expectations of record values. J. Chungcheong Mathematical Soc. 22:149-153.

|

|

|

|

Kabeer N (2005). Is Microfinance a "Magic Bullet" for Women's Empowerment? Analysis of Findings from South Asia. Economic and Political weekly. 29:4709-4718.

|

|

|

|

Khavul S (2010). Microfinancing: Creating opportunities for the poor? Acad. Manage. Perspect. 24(3):58-72.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Khavul S, Chavez, Bruton G (2013). When institutional change outruns the change agent: the contested terrain of entrepreurial microfinance for those in poverty. J. Bus. Vent. 28(1):30-50.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Kirru JMM (2007). The Impact of Microfinance on Rural Poor Households' Income and Vulnerability to Poverty: Case study of Makueni District, Kenya. Unpublished PhD thesis University of Bonn.

|

|

|

|

Littlefield E, Murduch J, Hashemi S (2003). Is microfinance an effective strategy to reach the millennium development goals? CGAP focus note 24. P 11.

|

|

|

|

Littlefield E, Rosenberg R (2004), Microfinance and the Poor. Breaking down walls between

View

|

|

|

|

Lucok, DA, Wesley JW, J. Charitha R, Gunasekera M (1995). The USAID Microenterprise Initiative in Sri Lanka. David GEMINI Technical Report No. 81. Colombo: USAID.

|

|

|

|

Lumpkin GT, Dess GG (1996). Clarifying the Entrepreneurial Orientation Construct and Linking It to Performance. Acad. Manage. Rev. 21(1):135.

|

|

|

|

Mosedale S (2003). Loan Empowerment and its importance, 3rd edition, McGraw Publication limited, Kenya. pp. 1-9.

|

|

|

|

National Women's Law Center (NWLC) (2014). Analysis of 2014 Census Poverty Data. [Online]

View

|

|

|

|

Newman A, Schwarz S, Borgia D (2014). How does microfinance enhance entrepreneurial outcomes in emerging economies? The mediating mechanisms of psychological and social capital. Int. Small Bus. J. 32(2):158-179.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Nunnally JC (1978). Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed., McGraw-Hill, New York, NY.

|

|

|

|

Ranasinghe SB (2008). Factors Contributing to the Success of Women Entrepreneurs in Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka J. Adv. Soc. Stud. 1(2):85-110.

|

|

|

|

Robinson MS (2001). The microfinance revolution. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Schreiner M, Colombet HH (2001). From Urban to Rural: Lessons for Microfinance from Argentina. Development. Policy Rev. 19(3):339-354.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Senanayake SPM, Premaratne SP (2005). Microfinance for accelerated development in Sri Lanka: Need for Private Public Donor Partnership, Sri Lanka Economic Association, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

|

|

|

|

Sharma VM (2001). Quantitative target display: a method to screen yeast mutants conferring quantitative phenotypes by 'mutant DNA fingerprints'. Nucleic Acids Res 29(17):E86-6.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Seibel HD (2005): Does History Matter? The Old and the New World of Microfinance in Europe and Asia, Working paper / University of Cologne, Development Research Center,No. 2005,1.

|

|

|

|

Singh NT (2009). Micro Finance Practices in India: An Overview. Int. Rev. Bus. Res. Papers 5(5):131-146.

|

|

|

|

Steinwand D, Bartocha D (2008). How Microfinance Improves Lives in Sri Lanka, Sri Lankan – German Development Cooperation.

|

|

|

|

Yang D (2008). International Migration, Remittances and Household Investment: Evidence from Philippine Migrants' Exchange Rate Shocks. Econ. J. 118(528):591-630.

|