ABSTRACT

This study aims to determine the attitudes of prospective teachers studying pedagogical formation education towards citizenship and citizenship education based on their gender, area of specialization, ethnicity and geographical area. This study explains the global implications of the concepts of citizenship, and citizenship education. A quantitative approach using questionnaire survey was adopted for this study. The sample of the study consists of 460 prospective teachers. They were selected from 1000 prospective teachers studying pedagogical formation education in 2016 to 2017 academic year, with maximum variation sampling method. For data collection, patriotism attitude scale and patriotism education scale were used. Patriotism attitude scale involves ''blind citizenship'' and ''constructive citizenship'' while patriotism education scale involves a single dimension. The data collected were analysed with independent sample t test, one way Anova, least significant difference (LSD), Bonferonni, Dunnett’s C as well as mean, and standard deviation. The investigation revealed that there was a significant difference in the attitudes of the prospective teachers towards citizenship and citizenship education based on their area of specialization and ethnicity, but there was no difference in their attitude in relation to their gender and geographical location. In other words, the conclusion drawn is “gender” and “geographical area” variables did not play a crucial role in the formation of prospective teachers’ attitudes towards citizenship (either blind citizenship or constructive citizenship), and towards citizenship education; although “ethnicity” and “major” variables played an important role in their attitudes towards citizenship and citizenship education. On one hand, those who called themselves Kurds and those who called themselves Turks had different understanding of citizenship and citizenship education. On the other hand, those that participated in the pedagogical formation program from natural sciences departments and those that participated in the program from humanities departments had a distinct understanding about citizenship and citizenship education.

Key words: Citizenship, citizenship education, teacher education.

Science, scientific attitudes, and scientific beliefs seem to be crucially effective in the formation of the lifestyles of modern societies as well as in forming their understanding of citizenship and citizenship education. Pepeler (2012) talks about “an education mentality” which primarily focuses on the technological and practical efficacy of education. He contrasts it with an education policy in which thought exercises are of primary importance through which students gain some crucially positive attitudes and values that help them become responsible citizens in addition to gaining technological expertise, skills and knowledge required for their major education. This point will be evaluated later, hinting on the fact that the importance of the humanities has gradually decreased in modern education institutions due to some economical and practical concerns which make students and prospective teachers focus merely on the short-term consequences of education.

Citizenship and Human Rights Education (CHRE) is one of the top, ''indispensable'' priorities of the modern society. Societies living in different geographical locations need to create better communication with other societies because of global requirements. The continuity of this communication in a healthy way can only be possible with a universal understanding of citizenship and human rights. For this reason, “citizenship” and “human rights” are among the most important junctive points through which modern societies can create their best international relations. This is what motivated us to investigate and interpret the prospective teachers’ attitudes towards citizenship and citizenship education.

Citizenship and human rights are different yet complementary notions. As a notable universal application starting with Magna Charta, citizenship and human rights became an indispensable priority of almost all societies with its continuing development cycle in the form of published international declarations. To be specific, human rights and citizenship violations motivate societies to make use of effective sanctions including declaration of war, if not frequently.

Therefore, to develop a modern society without violence, the confusion regarding citizenship and human rights needs to be clarified and put into effect by means of education. For this reason, the theoretical, scientific and applicative aspects of this process deserve careful attention and investigation. The number of researches on such an important topic is unfortunately very limited. It seems more clearer that the more importance we attach to citizenship and human rights in our education programs, both in terms of quality and quantity, the more optimistic and humane world we may hope for our prospective children.

The concept of homeland signifies the country where one is born and raised or is where one feels attached to emotionally (Büyük, 1986) or a place where common life and common ideals take place in such a way as to allow for individual definitions, abilities and forms of expression. People who share similar culture and ideals and who have the common bond of unity experience such a partnership in a specific piece of land. Homeland is defined as the place where this partnership takes place (DoÄŸan, 2001).

We can define the concept of homeland, which we also refer to as country today, as an area of sovereignty and a piece of land in its borders (DoÄŸan, 2001). It is clear from the definition that this border is a piece of land including both underground and above ground, on which both aliens and citizens live, in which a series of rules are in place, to which citizens relate with the bond of citizenship.

However, the concept of homeland in terms of quality has been understood and interpreted differently in the historical process. In other words, there are important differences between the modern and traditional definitions of homeland. These definitions may also differ from age to age, from society to society, and from culture to culture, depending on which understanding and practices of education and which forms of government are endorsed.

In brief, "homeland" is where people are not only born and grown up, but also equipped with social values, where they acquire their national identities. Therefore, it is a sacred place where humans are praised for being a part of, honoured to serve and they are ready to make every sacrifice including facing death if necessary (Yılmaz, 2000).

Citizen

A citizen is synonym for a member of a nation (Büyük, 1986); a person who has civil and political rights, and suffrage in a state (Antonym of alien) (Büyük, 1986). According to Harvey (1997), a citizen is a person that lives in a state, protected by law, has right to vote in elections, is able to understand responsibilities of a citizen protected by that law, pays taxes and accepts rights of others. According to Vural (2000), citizens are all people living in the same homeland and who are connected to the same state with the same bond of citizenship. All states determine who a citizen is with the law. In the Constitution of The Republic of Turkey, article 66 says, ''every person who is bonded to Turkish State with the bond of citizenship is Turk''.

Citizenship

Today, the concept of citizenship is defined differently in different countries according to their social, cultural, economic and geo-political positions. However, as the world becomes a global village, it is inescapable that these definitions have some common reference points. While Balasubramanian (quoted: Rozemeijer, 2001: 16) defines citizenship as a person’s ability to contribute to the society's progress and development, Monoye (quoted: Rozemeijer, 2001: 16) defines it as relationships between people and the state. Therefore, it is a process that consists of mutual duties and responsibilities between the individual and the state. The nature of this process is determined by the state's culture, lifestyle, and political structure, geopolitical and economical features. But those determinative features, especially with the help of the recent rapid changes and social relations seem to have turned into a universal feature.

Meaning of citizenship education

If we consider citizenship as a legal connection between a citizen and the state, citizenship education is a preparatory education activity for individuals to take part in this process. According to Davies (2000), citizenship or citizen education is the process of activities that fully prepare young people for their roles and responsibilities as citizens.

The word citizenship implies ''right'' and ''responsibility''. When we say ''right'', what comes into mind is the right given to an individual by a certain society and when we say ''responsibility'', we remember the duties of an individual to a society or state. These two elements need to be considered together with the concept of citizenship. In democratic societies, ‘'right'' and ''responsibility'' are discussed together; in fact, in those societies, rights have more priority. On the other hand, in societies without complete democratization, the aspect of duty is given more priority and concept of rights are kept in the dark (Kıncal, 1998).

In the report ''Democracy Teaching and Citizenship Education in Schools'' in 1998, citizenship education is defined as the act of educating individuals who know and act upon their duty as citizens at the same time; it is not only providing knowledge about citizenship and society but also teaching other developments, skills and insight to explain the large subjects like environmental education, development education and peace education (Davies, 2000).

Keeping this in mind, ''citizenship education'' may be defined as a doctrine that gives information about the rights and duties of the individuals living in an organized society, the duties and responsibilities of the people to each other and their relations with various institutions and organizations in society (Nomer, 1983). Therefore, citizenship education is not only based on knowledge, but also focuses on the act of knowing the rights and duties of individuals within and outside the society.

It is evident that, there is no such thing like freedom without any limits. Such kind of freedom is only partially feasible for a limited number of individuals in societies that are governed by dictators. This is contrary to the common principles of today's understanding. The intensity of human relations and globalization has made these kinds of practices almost impossible. Recently, because of those reasons many governments have had to leave their place to more democratic and liberal governments. It will be possible for all people to have equal rights and duties only through just usage of rights and duties.

The state will gain more respect in an environment where separations and privileges are gradually erased. As a natural result of these developments, the concept of the state which is suspicious about its citizens will be abandoned; instead, a concept of state that trusts on its citizens will rise.

Objectives of citizenship education

Active citizenship education involves three main interrelated qualities. These are social and moral responsibility, social participation and political consciousness. To create this consciousness the following must occur:

1. Helping young people understand their social and moral responsibilities towards each other and against authority.

2. Creating opportunities for children to be active in school and the social environment.

3. Teaching young people to understand how a broad political system works, helping them learn how they can function in such system by becoming active, critical and responsible citizens. These aspects are considered the necessary subjects in citizenship education (McGonigle, 1999).

Certainly, the duties and responsibilities of citizens are not just to abide by the law and to be respectful. Adopting the customs and traditions of the society, trying to protect them, and most importantly, to carry the culture of the society to the next generations are also required (Büyükkaragöz and Kesici, 1998). Because culture exhibits dynamic features, it is necessary for citizens to get education to be creative and especially to be adaptable to recent changes. Today, certain behaviours limited to a single culture are about to vanish. For this reason, one of the most important functions of education is its unifying power which is value-laden.

Aspects of citizenship education

The tribal culture in traditional societies has given way to universal culture, and traditional education has given its place to modern education; and antidemocratic governments have left their place to democratic governments. No longer lives the individual only in his own society but is almost intertwined with other societies. This requires active harmonization of individuals with the lifestyles of other societies. If democracy is based on personality rights, freedom of expression and thought, the content of the education system should always provide the young with these freedoms (Menter and Walker, 2000).

When we look at educational objectives, we observe that this covers areas such as individuals, society and subjects (Tekin, 1984). We see that these dimensions cover firstly the individual, secondly the country and thirdly the world in which an individual lives with people from other countries (Kıncal, 1998).

Lynn gives the following explanation regarding this issue: "The goal of citizenship education in schools and colleges is to make individuals value the features of democratic participation, to ensure the rights and responsibilities at a high level and to make choices without the need for responsibility for their development within active citizenship awareness. Citizenship education involves learning and developing human rights and responsibilities: social and moral responsibilities, community involvement and politics. Citizenship gives students an effective role in society and the region, as well as knowledge, skills and understanding at national and international levels" (Davies, 2000).

Citizenship is simply the fulfilment of the rights and obligations of the individual in the framework of law and certain principles. One of the main tasks of education is to help them socialize or, in other words, to make them sociable. Smith, Stanley and Shores (quoted, Fidan and Erden, 1993: 19) broadly define education as all social processes that influence the teaching of individual society standards, beliefs and ways of living. Citizenship is the resulting reflection of events that are much more extensive than these.

Another important point in citizenship education is that it includes both national and international aspects. People get into relations with foreigners, travel with them, build family bonds with them, and interact with them through internet. Global citizenship requires being a part of a global community or living in confidence in different communities around the world. Oxfam (quoted: Harvey, 1987) suggests that a global citizen should have the following characteristics:

1. Being aware of the world and seeing their role as world citizens.

2. Respect for different values.

3. Being willing to build more equal and powerful peace in the world.

4. Taking responsibility to make others active.

According to Harvey (1997), citizenship education should have the following three features:

1. Social and moral responsibility: To learn that both self-reliance, social and moral behavioural responsibilities belong to one group in the sense of authority.

2. Learning to live with society: Learning to be helpful to their neighbours and in their lives.

3. Political consciousness: To learn how to be influential in institutions, solving problems, democratic practices and in social, national, regional, and political contexts.

Jones and Theresee (2001) argue that there are five main issues related to citizenship:

1. Politic consciousness

2. Rights

3. Differences between duties and rights

4. Interests in benefits of democratic values

5. Citizen rights and public participation

Again, referring to Crick (1998) report in the same article, it is said that the report focuses on three characteristics, and that these features emphasize unity in the formation of citizenship. These three characteristics are: Social and moral responsibilities, social participation and political consciousness.

Purpose of the study

The purpose of this study is to determine the attitudes of the prospective teachers towards citizenship and citizenship education depending on some variables, and to evaluate the concepts of citizenship and citizenship education.

Sub problems of research

The sub-problems that need to be answered in the framework of the problem described above are:

Do prospective teachers’ attitudes towards citizenship and citizenship education differ according to:

1. Their gender

2. Their major

3. Ethnicity

4. Geographical area where they spend most of their lifetime?

This section contains information about the model of the research, the population and sample, data collection tools, and data analysis.

Research model

Survey-type research model was used in this study because the aim of this research is to investigate the attitudes of prospective teachers studying pedagogical formation education to citizenship and citizenship education and to investigate relations with various variables. The survey model is a research approach used to describe past or existing situation as it exists (Karasar, 2005).

Population and sampling of the study

The population of the research consists of 1000 prospective teachers studying Pedagogical Formation Education in 2016 to 2017 academic year in Faculty of Education at Inonu University. They are from different undergraduate education departments like social sciences, natural sciences, theology, art, health etc. The maximum variation sampling method was used in the selection of the research sample. For this reason, the research sample was chosen to reflect the variables (sex, department, region, ethnicity etc.) of the study. 460 prospective teachers participated voluntarily in the research. 460 forms were returned from the questionnaire distributed. 51 forms were not used for analysis. These forms were removed during the process of checking the validity, reliability and normality of the study. A total of 409 forms were used for data analysis.

Data collection tools

The survey form used as a data collection tool in the research consists of three parts:

1. Personal information form

2. Patriotism attitude scale and

3. Patriotism education scale.

Personal information form

In the personal information form used to determine the demographic characteristics of the potential teachers in the survey, the participants were asked about their gender, teaching areas, the way they describe themselves, and the geographical regions where they have spent most of their lives.

Citizenship attitude scale

This scale was adapted to Turkish by Yazıcı (2009) and Schatz et al. (Schatz (1999; quoted, Yazıcı, 2009)) which was developed to differentiate between blind and constructive patriotism and their relation to other social phenomena. The original scale was prepared by Schatz, Staub and Lavine with an appeal to the preliminary work of Schatz (1994). In the internal reliability analysis of the scale used in this study, the Cronbach's alpha coefficient was calculated as 78. To determine the structural validity of the scale, descriptive factor analysis and Varimax Rotation Method was used. In the reliability study, the number of factors is limited to two. In the factor analysis, blind patriotism items were collected under the first factor and constructive patriotic items were collected under the second factor. The Patriotism Attitude Scale consists of 20 items with a blind patriotic dimension of 12, and a constructive patriotic dimension of 8. The responses to the 5-point Likert-type scale are; "I strongly disagree", "I disagree", "Undecided'', ''I agree" and "I strongly agree".

Citizenship education scale

The scale developed by Yazıcı (2009) was used to measure the attitudes towards patriotism education. The one-dimensional scale aims to measure the general attitude of teachers towards patriotism education. There are 10 questions on the scale. The responses to the scale developed on 5-point Likert-type scale are; "I strongly disagree", "I disagree", "Undecided'', ''I agree" and "I strongly agree"

Data analysis

Data collected from the study are analysed with independent sample t test according to gender; while the data were analysed with one way Anova, LSD, Bonferonni, Dunnett’s C according to major, ethnicity and geographical area. Additionally, the mean, standard deviation is used for the analysis.

In this section, the results of the analysis of the attitudes of the prospective teachers towards citizenship and citizenship education based on their gender, department, ethnicity and geographical area are given. The findings are interpreted in accordance with the results of analysis.

Does the attitude of the prospective teachers towards citizenship and citizenship education differ according to their genders?

Independent sample t test was used to analyze the attitudes of prospective teachers towards citizenship and citizenship education according to gender. The results of the analysis are given in Table 1. Table 1 shows the attitudes of prospective teachers towards blind citizenship, constructive citizenship, and citizenship education.

Based on the data, it is concluded that the differences between the sexes are not significant. However, when the average scores are examined, it is observed that the blind citizenship scores in both women and men are higher than the scores in other dimensions. This result shows that people are not much interrogative about the formation of citizenship attitudes. Blind citizenship scores x = 33.30 to 33.71, constructive citizenship scores x = 30.85 to x = 30.88, and citizenship education attitude scores x = 29.61 x = 28.64.

Does the attitude of the prospective teachers towards citizenship and citizenship education differ according to their majors?

Variance analysis was conducted to determine the difference of attitude toward citizenship and citizenship education in accordance with the majors of prospective teachers. One Way Anova results are shown in Table 2. According to the One-Way ANOVA results, it was determined that there is a significant difference in the dimensions of constructive citizenship and citizenship education. Post hoc tests need to be performed to determine which groups differ between these two dimensions. It is necessary to first determine whether the distribution of variances is equal to decide which post hoc test is to be performed. So, the results of the levene test should be examined. The results of the Levene test are given in Table 3.

Significant differences were found in the Citizenship Education dimension of the results of the Levene test. This result shows that the variances for the dimension constructive citizenship are equally distributed and the variances for the dimension citizenship education are not equally distributed. Least significant difference (LSD) test can be used to determine the difference between the groups in dimension of constructive citizenship. In the dimension of citizenship education, Dunnett’s C was used in the post hoc tests because the variances were not equally distributed (Table 4).

According to Table 4, there were significant differences between the mean scores of the attitudes of the pre-service teachers’ major they studied. The LSD test was used to determine which groups have significant differences in constructive citizenship dimension. The results of the analysis are given in Table 4.

From the analysis of the results in the dimension of constructive citizenship attitude, the difference between the social sciences and natural sciences, the social sciences and the fine arts, the natural sciences and the health, the natural sciences, the theology and the natural sciences, and other fields are significant. Mean score of social sciences is highest in constructive citizenship. This can be considered as an expected result because the prospective teachers of social sciences are more knowledgeable and experienced about the citizenship.

The Dunnett’s C test was used to determine which groups have significant differences in constructive citizenship dimension. From the analysis of the results in the dimension of citizenship education, there is a difference between fine art and theology, other major and theology. This result is quite significant. In social sciences where citizenship education is also related, it could be expected that attitude scores are higher than other groups. Citizenship attitude score was found to be very low in theology group. It can be argued that this situation is caused by the understanding of citizenship depending on the religious values that the group has. As a result, it is possible to find similarities or differences in this work by examining the citizenship attitudes of other religions more extensively.

Do prospective teachers’ attitudes towards citizenship and citizenship education differ according to their ethnicity?

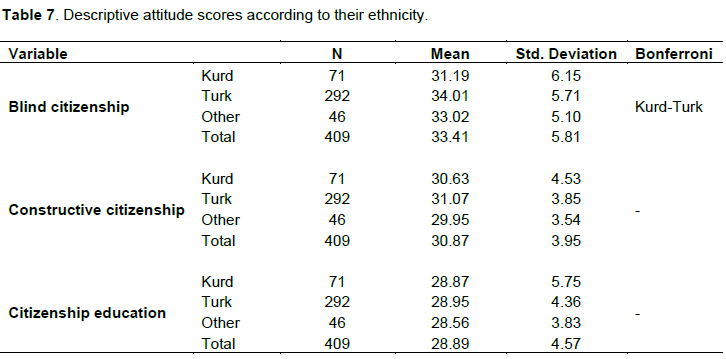

Variance analysis was conducted to determine the change of prospective teachers’ attitudes toward citizenship and citizenship education according to their ethnicity. One Way Anova results are shown in Table 5.

According to the One-Way ANOVA results, it was determined that there is a significant difference in the dimensions of blind citizenship. Post hoc tests need to be performed to determine which groups differ between these two dimensions. It is necessary to first determine whether the distribution of variances is equal to decide which post hoc test is to be performed. So, the results of the Levene test should be examined. The results of the Levene test are given in Table 6.

Significant differences were not found in the blind citizenship dimension of the results of the levene test. This result shows that the variances for the dimension of blind citizenship are equally distributed. Bonferonni test can be used to determine the difference between the groups in dimension of blind citizenship (Table 7). As seen in Table 7, there are significant differences between the mean scores of the attitudes of the prospective teachers in dimension of blind citizenship according to their ethnicity.

According to bonferroni test results, it was determined that the difference is between Turkish and Kurdish. From this, it was observed that the mean score of blind citizenship of those who call themselves Turkish is higher than the mean score of those who call themselves Kurdish (Turkish  = 34.02 and Kurdish  = 31.20).

In other words, the group that calls themselves Kurdish has a more critical character than the group, regarded as Turkish, about the citizenship of the group. In addition, according to the mean scores of attitudes based on their ethnicity, it is observed that the blind citizenship average score ( - = 33.41) is higher than the constructive citizenship score ( = 30.87) and the constructive citizenship score is higher than the citizenship education mean score.

Do prospective teachers’ attitudes towards citizenship and citizenship education differ according to geographical area where they spent most of their lifetime?

Variance analysis was conducted to determine the change of prospective teachers’ attitudes toward citizenship and citizenship education according to geographical area where they spent most of their lifetime. One Way Anova results are shown in Table 8. According to the One Way Anova results, it was determined that there is no significant difference in the dimensions of blind citizenship, constructive citizenship and citizenship education. The mean scores range from  = 28.00 to  = 34.15 as shown in Table 9. When attitude scores according to geographical regions are examined, it is observed that the highest attitude scores belong to the Mediterranean region in blind citizenship, central Anatolia region in constructive citizenship and Mediterranean regions in citizenship education.

CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS

The main concern of this study is twofold: to determine the attitudes of prospective teachers who participated in pedagogical formation education towards citizenship and citizenship education, and to evaluate the consequences with the aim of shedding light on understanding the nature of future orientation of education.

The results of the empirical findings of this study provided us with the fact that perception of citizenship and citizenship education among teacher candidates are mostly formed and affected with their ethnic beliefs and fields of study, or majors. As for the first of these two variables, ethnicity seems to be significantly functional in prospective teachers’ understanding of citizenship and citizenship education. This is probably the result of a minority psychology.

Keeping the fact that prospective teachers coming from ethnic minority have a different picture of citizenship and citizenship education is what future education programs should give priority to in preparing their young generations for a peaceful world. While citizenship and human rights in democracies, rights in developed societies and responsibilities in totalitarian societies are indispensable for each other, cultural and educational backgrounds of societies seem to have been shaping their putting into practice of these crucial concepts.

As for the second variable, major or main field of study of prospective teachers seems to be functional in their understanding of citizenship and citizenship education. The results of the investigation show us that the differences between the mean scores of attitudes of blind citizenship, constructive citizenship and citizenship education for the prospective teachers were not significant. However, a difference of attitude was observed between the average scores of the attitudes of the candidate according to their majors, or fields of study.

To be specific, the difference between the social sciences and the natural sciences, the social sciences and the fine arts, the digital sciences and the health, the natural sciences, the theology and the natural sciences, and other fields are significant. In social sciences attitude scores are higher than all the other groups, while citizenship attitude score is very low in theology group. This is a result of their religious world view from a first impression. However, the more important point here is to understand the impact of religion on prospective teachers’ understanding of citizenship.

The findings of the study lead us to thinking that value-laden concepts such as citizenship and citizenship education need to be based on a universal and a philosophical understanding which is free from departmental and ethnical presumptions and prejudices in educational process. Global peace of the world seems to be dependent upon universally accepted beliefs in the final analysis.

Nowadays, universities all over the world seem to be giving the priority to practical and economical aspects of education. This involves providing students with technical expertise, and skills regarding their field of study, ignoring the significance of the project of making them sensitive and responsible citizens. Promoting and developing the humanities, or social sciences departments might be helpful in this regard. In other words, the departments and fields of studies focused on developing our humane values need to be revitalized in education process.

In sum, the social structure which is formed not only by the expectations of teacher candidates but also by the expectations of all groups that constitute the society needs special attention and deliberation. That the laws are shaped such as to meet the expectations of every member of society is another crucial point. There is no doubt that the educational activities need be carried out in accordance with rational, universal and culture-independent values and beliefs. This seems to be indispensable in creation of universal citizens.

The possibility that prospective teachers are the intermediate stuff in transmitting technical, and professional knowledge and skills to new generations seems to be a great threat to the future formation of educational process. While the educational institutions are providing the prospective teachers with the necessary equipment they should not take the risk of setting aside the humane values that make professional and technical acquisitions meaningful in the final analysis. All technical and technological achievements of educational process need to be subjected to a universal and humanitarian understanding of citizenship.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Büyük L (1986). Sözlük ve Ansiklopedisi- Milliyet Yayınları- Ä°stanbul.

|

|

|

|

Büyükkaragöz S, Kesici Åž (1998). Demokrasi ve Ä°nsan Hakları EÄŸitimi, Türk Demokrasi Vakfı Yayınları, Ankara.

|

|

|

|

|

Chauhan L (2000). Citizenship Education And Human Rights Education-Developments And Resources In the UK, The British Council Design Department, Public Policy Research Associates.

|

|

|

|

|

Crick B (1998). Education for citizenship and the teaching of democracy in schools Final report of the Advisory Group on Citizenship. Qualifications and Curriculum Authority 29 Bolton Street London W1Y 7PD.

|

|

|

|

|

Davies L (2000). Citizenship Education And Human Rights Education-Key Concepts and Debates, The British Council Design Department, University of Birmingham.

|

|

|

|

|

Doğan İ (2001). Vatandaşlık Demokrasi ve İnsan Hakları, PegemAYayıcılık, Ankara.

|

|

|

|

|

Fidan N, Erden M (1993). EÄŸitime giriÅŸ. Alkim Yayinevi. Ankara.

|

|

|

|

|

Harvey Mc. G (1997) "A Curriculum For Global Citizenship", Times Educational Supplement, 97 Issue 4242 P:II, 1/6p

|

|

|

|

|

Jones S, Therese O (2001). Rethinking People's Political Participation Paper Presented to the Political Studies Association, Annual Conference- University of Manchester.

|

|

|

|

|

Karasar N (2005). Bilimsel AraÅŸtırma Yöntemi. Ankara: Nobel Yayın-Dağıtım.

|

|

|

|

|

Kıncal RY (1998). Vatandaşlık eğitiminin sınırları, Felsefe Kongresi (27-29 Mayıs), Erzurum.

|

|

|

|

|

McGonigle Par J (1999). New Approaches to Citizenship Education and the Teaching of Democracy in School from 2000", Oxford, Royaume-Uni, 2-7 November.

|

|

|

|

|

Menter I, Walker M (2000). How would a well-educated young citizen react to the Stephen Lawrence inquiry? An examination of the parameters of current models of citizenship education. Curriculum J. 11(1):101-116.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Nomer E (1983) . VatandaÅŸlik Hukuku, Filiz Kitapevi, Ä°stanbul.

|

|

|

|

|

Pepeler E (2012). Ä°lköÄŸretim 4. Ve 5. Sınıf Fen Ve Teknoloji Dersi Ä°le Matematik Dersinde Üstün Zekâlı ÖÄŸrencilere Yönelik Uygulamaların DeÄŸerlendirilmesi, yayınlanmamış Doktora tezi, Ä°nönü Üniversitesi EÄŸitim Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Malatya.

|

|

|

|

|

Rozemeijer S, Renato M (2001). Net forum, ICE 2001, Final Report, Geneva.

|

|

|

|

|

Schatz RT, Staub E, Lavine H (1999). On the varieties of national attachment: Blind versus constructive patriotism. Political Psychol. 20(1):151-174.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Schtaz R (1994). On Being a Good American: Blind Versus Constructive Patriotism, Yayınlanmamış doktora tezi, University of Massachusetts.

|

|

|

|

|

Tekin H (1984). EÄŸitimde Ölçme ve DeÄŸerlendirme. Hasâ€soy Matbaası, Ankara.

|

|

|

|

|

Vural Ä°H (2000). Ä°lköÄŸretimVatandaÅŸlik ve Ä°nsan Hakları Egitimi, Serhat Yayınları, Ä°stanbul.

|

|

|

|

|

Yazıcı F (2009). Vatanseverlik EÄŸitimi - Sosyal Bilgiler ve Tarih ÖÄŸretmenlerinin Tutum ve Algılarına Yönelik Bir Çalışma (Tokat ili örneÄŸi). Yayınlanmamış Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Gazi Osman PaÅŸa Üniversitesi, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, Tokat.

|

|

|

|

|

Yılmaz D (2000). Üniversiteler Ä°çin VatandaÅŸlık Bilgisi. Çizgi Kitabevi, Konya.

|

|