ABSTRACT

English and Turkish languages have different orthographies. The orthography of English is considered relatively deep since many English letters can correspond to more than one sound; many sounds can be represented by more than one letter and English has a number of consonant digraphs/clusters such as th, sh, ch, and ck to represent a single sound. Whereas, the Turkish orthography presents a good example of the total shallow orthography as each letter represents only one phoneme and each phoneme is represented by only one letter. This difference can be problematic for Turkish EFL learners during the writing activity. Therefore, the primary aim of this experimental study was to explore the effects of games on the development of the writing skills of primary school EFL learners. 42 primary school EFL students voluntarily participated in the study and they were grouped as control and experimental. The experimentation took 9 weeks and in the last week of the study both groups were given a dictation exercise to find out if any differences existed. The results demonstrated that games positively affect primary school EFL learners’ writing skills and therefore it was recommended that games should be used during the teaching of writing skills in primary school EFL contexts.

Key words: EFL, primary school, writing skills, games.

The most recent amendment that has been put into effect about the teaching of English as a compulsory primary school subject in Turkish state primary schools (MoNE, 2018) requires that listening and speaking are prioritized as language skills while reading and writing skills are offered with limited application. However, since knowing a language is a complex and four-language-skills-integrated process, no matter how much the students are successful in listening and speaking tasks, without appropriate reading and writing, a language cannot be fully comprehended (Wright, 2010). As one result of this prioritization, primary school EFL learners are experiencing difficulties during writing tasks. One of the main reasons for this situation can be the English orthography (Hannell, 2008) alongside with L1 influence. One may think that it is as unimportant to write at the isolated-word-level; however, as they are young learners, this problem may lead to bigger issues in their future second language learning experiences. The students with poor spelling abilities may “hold back from seeking or accepting roles that are likely to expose poor spelling; avoid further education, training or promotion if they fear that their spelling skills will let them down; and feel inadequate in comparison to others who can spell well” (Hannell, 2008: 2).

Let us now briefly look into the main differences between the English and Turkish orthographies. There are 26 letters in the English Alphabet: 5 vowels (a,e,i,o,u) and 21 consonants (b,c,d,f,g,h,j,k,l,m,n,p,q,r,s,t,v,w,x,y,z) (Roach, 2009). Although both languages use a very similar alphabet, English phonology, based on the vowel system that includes short-long vowels, diphthongs, trip thongs and consonants that are categorized according to the place of articulation and manner of articulation (Roach, 2009) is highly affecting the orthography. “The letters do not stand for segments that are acoustically isolable in the speech signal”; thus, consonants and vowels are not “neatly segmented in correspondence with the way they are represented in print” (Shankweiler and Lundquist, 1992: 180). Therefore, the orthography of English is considered relatively deep since many English letters can correspond to more than one sound (e.g. c for /k/ in cat and /s/ in cinema), many sounds can be represented by more than one letter (e.g. c,k, or q for /k/), and English has a number of consonant digraphs/clusters such as th-, sh-, ch-, and ck- to represent a single sound (Miller, 2019: 3). Likewise, Yule (2014) defines the English writing system as being alphabetic in a very loose sense in that there are irregular correspondences between sounds and their symbolic representations.

On the other hand, there are 29 letters: 8 vowels (a,e,ı,i,o,ö,u,ü), 20 consonants (b,c,ç,d,f,g,h,j,k,l,m,n,p, r,s,ÅŸ,t,v,y,z) and the “silent g” written as “ÄŸ” lengthens the preceding vowel, but it is not a phoneme by itself (DurgunoÄŸlu, 2006). Turkish presents a good example of the total shallow orthography as each letter represents only one phoneme and each phoneme is represented by only one letter. DurgunoÄŸlu (2006) adds that there is no phoneme in the spoken word excluded in spelling except the written form of the borrowed words from other languages (e.g.tren[train], pronounced as /tiren/). The relation between letters and phonemes is isomorphic and exhaustive (Katz and Frost, 1992). Since Turkish is an agglutinative language,vowel harmony, in which all-possible combinations of the distinctive features (front-back, high-low, and rounded-unrounded) are observed, is one of the important characteristics in Turkish phonology as it decides the phonemes in the word-formation process which follows a predictable pattern (Kornfilt, 1990 as cited in DurgunoÄŸlu, 2006). Consonant clusters are not allowed in the beginning of Turkish words but in the ends of the syllables such as çift-lik [farm] and kent [city]. Therefore, Turkish syllables are in four simple syllables types: V, VC, CV and CVC, and the most frequent form is CV (DurgunoÄŸlu, 2006). When compared to English, Turkish has fewer monosyllabic words which are phonologically consistent with the rules of the language (DurgunoÄŸlu, 2006); most Turkish words are polysyllabic. In Turkish, as the spelling-sound correspondence is direct, once given the rules, anyone can immediately read or write the words correctly (Besner and Smith, 1992).

As a result, Turkish primary school EFL learners have hesitations and make mistakes during the writing process, mainly due to the orthographic differences of the English and the Turkish languages. On this matter, Miller (2019) argues that the orthography of English makes spelling words especially difficult for learners whose first language has a shallower orthography. Miller affirms that learning a new orthography is learning a new way of understanding visual information and how it corresponds to phonological information. Therefore, readers/writers must pay attention to the arbitrary or unusual pronunciations and spellings of irregular words in English (Besner and Smith, 1992). Thus, the development of L2 spelling skills is not an easy process but it is only possible with appropriate practice.

According to Mattingly (1992), without a spelling system, orthography is not productive: the invention of the one requires the invention of the other. Today, it has become necessary for all members of a modern society to become able to communicate in writing by committing “spelling patterns” on paper or on screen (Montgomery, 2007).As an important sub-skill of writing, spelling helps writers for accurate communication and correct spelling helps learners with writing fluency, good expression and confidence (Hannell, 2008). The spelling skill is mostly linked to the reading skill as both reading and writing depend upon the alphabetic principle and they are completing each other and use similar or common knowledge to be achieved (Shankweiler and Lundquist, 1992). “When learning to read in English, a learner must view printed letters (graphemes), decode their sounds, and combine those sounds together to form words” (Miller, 2019: 1). However, English language readers “have probably had the experience of being unsure how to spell some words” (Shankweiler and Lundquist, 1992: 183), because, compared to reading, spelling requires additional knowledge and finer-grained, more explicit vocabulary knowledge at both the spoken and written levels.

According to Montgomery (2007), in a method called “emergent writing” (developmental writing or creative spelling), teachers encourage their students to practice more spelling until they achieve the standard orthography. When encouraged to invent spellings for words, young children invent a system that is more compatible with their linguistic intuitions than the standard system and develop themselves through time (Shankweiler and Lundquist, 1992: 183). To be a successful speller, one should have the cognitive components of the spelling skill and improve him/herself by time. During the experimentation of the present study games were used as a means of possible treatment to overcome spelling problems. Therefore, we should now turn our attention to games in EFL contexts. Ersöz (2007: 7) states that “games are highly motivating because they are amusing and interesting”. Similarly, according to Yolageldili and Arikan (2011), games are fun and enjoyable activities, which lead cooperation and social interaction. Children naturally play games in their lives (Ersöz, 2007) and playing a game is motivating for them, because it is a challenge, and they want to win (Rumley, 1999). Students become excited while playing, because the winner is not obvious till the end of the game which can be concluded as games “help and encourage many learners to sustain their interest and work”. In addition, during playing games, learners are required to work with others to be successful and most of them enjoy cooperation and social interaction and thus “when cooperation and interaction are combined with fun, successful learning becomes more possible” (Yolageldili and Arikan, 2011: 220). Another aspect of games is that they help to sustain quite long exchanges in L2 and as the language used for young learners is limited, this is vital for them (Rumley, 1999).

When we investigate the literature about spelling and games, we come to understand that almost all of the previous studies focused on the description and categorization of spelling mistakes. One such example was carried out by Kırkgöz (2010) who analyzed the 400 individual written errors in the essays of 72 adult Turkish EFL learners. She collected the data in three steps: the collection of sample errors, identification of errors and description of errors. Kırkgöz categorized errors as interlingual (subtitled as grammatical interference, prepositional interference, verb tense, and lexical interference) and intralingual (subtitled as over-generalization, use of articles, and redundancy). According to results, interlingual errors were higher in number, which revealed that the learners tended to transfer from their L1 (Turkish) in the L2 writing processes. Thus, the present study is unique for Turkish young learner EFL contexts in that it seeks for ways of solving the spelling problem faced by Turkish young EFL learners. The present experimental study is therefore of significant importance in that it seeks to address the following main question:

How do games affect the writing skills of primary school 3rd grade EFL learners?

With this main purpose in hand, the research will also focus on the following sub-questions:

(1) What are the differences regarding the participants’ success rates in the dictation exercise?

(2) What are the differences regarding he participants’ target vocabulary correctness rates in the dictation exercise?

Participants

A total of 42, 3rd grade students studying in a Turkish state primary school in the city of Burdur voluntarily participated in the current study in the second term of the 2018-2019 academic year. The students were all literate in Turkish and all were monolingual. They were all A1 level English learners and therefore considered as identical. They were divided into two classes as 3C and 3D, 21 students in each class. There were 11 males and 10 female students in 3C and 10 males and 11 female students in 3D. They were aged between 8.5 - 9.5 and all attended a two-hour (40 min each) compulsory English course per week. The classes were selected randomly as experimental and control.

Data collection instruments

Two spelling games were chosen and applied to the experimental group during the study at the end of every two-hour English lesson and data were collected by means of a Dictation Exercise applied to both groups at the end of the study. The games were: “Match the word to the image” and “Join up the words”, adopted from Cave (2006). It would be worthwhile, at this point, to briefly explain the games and the Dictation Exercise used in this study.

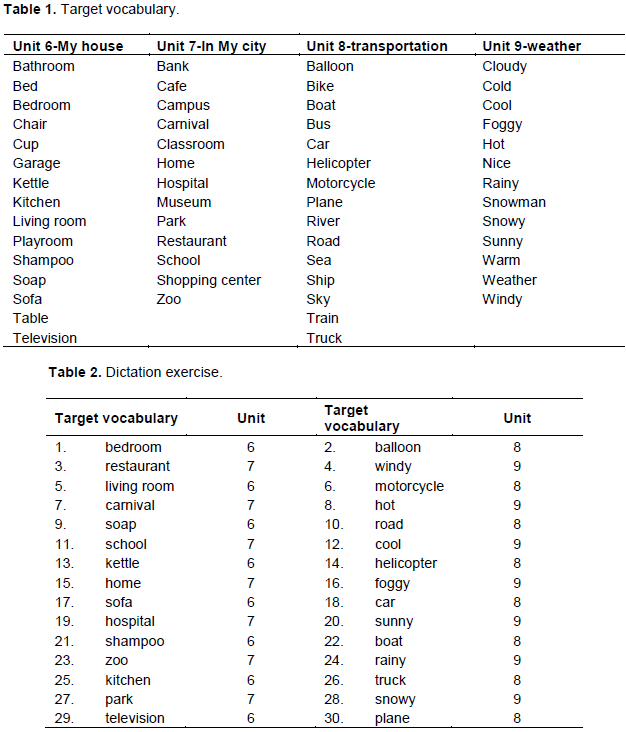

Match the word to the image: Picture flashcards and their accompanying written word-cards were created about the target vocabulary (Table 1). These were handed out to the students sitting in groups of four and they were asked to match the words and the flashcards. The first group to complete the correct matching was given a point.

Join up the words: The target vocabulary was written on word-cards and each word-card was cut in half. These were handed out to the students sitting in groups of four and they were asked to reconstruct the words by putting together the two halves correctly. The first group to reconstruct the correct word was given a point.

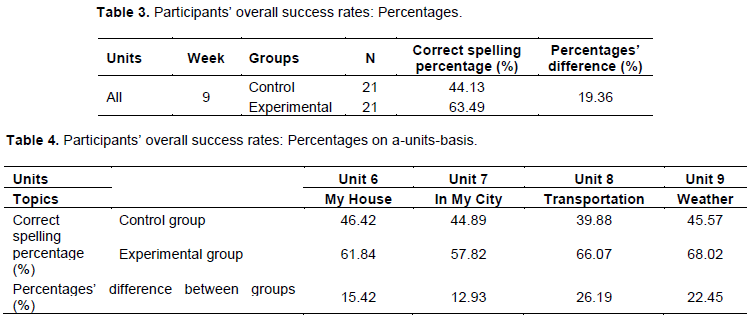

Dictation Exercise: The dictation exercise was applied to both groups in week 9, the final week of the study. Out of the 56 target vocabulary 30 were chosen randomly (Table 2). Each word in Table 2 was pronounced twice by the teacher and the students were asked to write the words on a blank paper that was pre-given by the teacher.

Procedure

The implementation process took 9 weeks in total and four units (6, 7, 8 and 9) from the 3rd grade 2nd term were covered during the first 8 weeks of the study. During this first 8 weeks, the experimental group played the two games at the end of every two-hour English lessons, but the control group did not. The English lessons of the two groups were on the same day. In week 9, both groups took the Dictation Exercise on the same day. The target vocabulary was chosen from the English program (MoNE, 2018) and from the book titled “Ä°ngilizce 3” provided by MoNE (DaÄŸlıoÄŸlu, 2015).

To maintain a clear understanding of the implementation process in this study, the first 2 weeks (Unit 6) and the last week (Week 9) will be explained in detail, as in weeks 3-8 the implementation was the same as in the first 2 weeks but with units 7, 8 and 9.

The topic for the first two weeks was “Unit 6, My House”. The target vocabulary was; bathroom, bed, bedroom, chair, cup, garage, kettle, kitchen, living room, playroom, shampoo, soap, sofa, table, and television. During the first hours (40 min) in the first two weeks, the students practiced the vocabulary by the help of flashcards and the pronunciations of the words were practiced as a whole-class. Then the teacher guided the students to do the related activities (e.g. repeating what they hear, matching by listening, reading and writing at word-level, and etc.) from the course book (DaÄŸlıoÄŸlu, 2015). During the second hours (40 min) in the first two weeks, the teacher continued with the activities and some practices were done using similar activities suggested in the book. Then, the experimental group played the “Match the word to the image” and the “Join up the words” games for 10-15 min. The control group did not play any games but continued with their routine activities. The same implementation was carried out during the remaining six weeks. In the final week of the study (week 9), the Dictation Exercise was administrated to both groups during class hours and the answer sheets were collected for further analysis.

Data analysis

Having finished the study, data were entered into the Microsoft Excel 2016 program, categorized and quantitatively analyzed by using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 packet program according to the Dictation Exercise results. The participants’ success rates and the participants’ target vocabulary correctness rates in the Dictation Exercise were categorized and analyzed according to group statistics and percentages.

Quantitative data gathered from the experimental and control group in the Dictation Exercise will be presented in tables. This will be done in two stages; first, analysis of the Dictation Exercise on the grounds of participants’ overall success rates; and, second, comparisons between groups according to participants’ individual target vocabulary correct spelling rates.

Participants’ overall success rates

Analysis of the dictation activity: Participants’ overall success rates

The dictation exercise was analyzed in two dimensions using Microsoft Excel 2016 and IBM SPSS Statistics 25 packet programs. The calculations were done by using the analysis of the participants’ group statistics in terms of the mean, standard deviation, standard error mean and means’ difference between groups.

First, the participants’ correct spelling percentages were examined and Table 3 exhibits the participants’ success rates in terms of correct spelling percentages and the percentage difference between groups. As we can clearly see in Table 3, the experimental group outperformed the control group on the grounds of correct spelling by 19.36%. The correct spelling percentage of the control group was 44.13, whereas the experimental group scored 63.49% in the Dictation Exercise. This finding demonstrates that games develop the writing skills of young EFL learners.

Second, the results of the Dictation Exercise were analyzed on a unit basis to find out in which units the participants performed better. Table 4 reveals the participants’ correct spelling percentages according to units, based on the Dictation Exercise in terms of correct spelling percentage and percentage difference between groups. As Table 4 demonstrates, when we evaluate the participants’ success rates on the grounds of a unit-based evaluation we shall come to see that the experimental group outperformed the control group in every unit. The experimental group was most successful in Unit 9 (with 68.02%) and least successful in Unit 7 (with a 57.82%). On the other hand, the control group was most successful in Unit 6 (with a 46.42%) and least successful in Unit 8 (with a 39.88%). The highest difference between groups occurred in Unit 8 (26.19%) and the lowest difference between groups occurred in Unit 7 (12.93%). Taken together, both groups best performance was in Unit 9 (113.59%), followed by Unit 6 (108.26%), Unit 8 (105.95%) and Unit 7 (102.71%).

Participant’ individual target vocabulary correctness rates

In this section, the data obtained from the dictations were analyzed quantitatively based on the participants’ correct spelling rates of the target vocabulary. The results will be presented according to units in tables; and this will be done by an analysis of the dictation exercise: target vocabulary correct spelling percentages.

Analysis of the dictation exercise: participants’ individual target vocabulary correct spelling percentages

The 30 target vocabulary, out of 56, dictated in the Dictation Exercise were analyzed, the results were calculated and then turned into unit-based percentage averages. The tables were constructed according to the dictation exercise results in terms of correct spelling percentages and percentage difference between groups.

Table 5 demonstrates “Unit 6 - My House” dictated target vocabulary correct spelling percentages and percentage difference between groups. The target word “bedroom” was the most correctly spelled word by the experimental group (85.71%) followed by “sofa, living room, kitchen, kettle and television” and the words “shampoo and soap” were the least correctly spelled words (47.62%). The control group, on the other hand spelled the word “sofa” most correctly (66.67%) followed by “bedroom and living room, kettle and soap, kitchen, television” and “shampoo” was the least correctly spelled word (19.05%). The most correctly spelled word by both groups was “bedroom” with a total of 142.85% and the least correctly spelled word by both groups was “shampoo” with a total of 66.67%. The word “soap” was the only case where the control group outperformed the experimental group. The highest difference between the groups occurred in the spelling of the words “bedroom and shampoo” (28.57%) and the lowest difference between the groups occurred in the spelling of the words “kettle, soap and sofa” (4.76%).

Table 6 demonstrates “Unit 7 – In My City” dictated target vocabulary correct spelling percentages and percentage difference between groups. The target word “zoo” was the most correctly spelled word by the experimental group (95.24%) followed by “park, carnival and home, hospital, restaurant” and the word “school” was the least correctly spelled word (19.05%). The control group also spelled the word “zoo” most correctly (76.19%) followed by “park, home, hospital and school, and carnival” and “restaurant” was the least correctly spelled word (19.05%). The most correctly spelled word by both groups was “zoo” with a total of 171.43% and the least correctly spelled words by both groups were “school and restaurant” with a total of 52.38% each. The word “school” was the only case where the control group outperformed the experimental group. The highest difference between the groups occurred in the spelling of the word “carnival” (28.57%) and the lowest difference between the groups occurred in the spelling of the word “home” when the scores were equal.

Table 7 demonstrates “Unit 8 – Transportation” dictated target vocabulary correct spelling percentages and percentage difference between groups. The target word “boat” was the most correctly spelled word by the experimental group (85.71%) followed by “car and helicopter, balloon and truck, plane, motorcycle” and the word “road” were the least correctly spelled words (38.10%). The control group, on the other hand spelled the word “car” most correctly (76.19%) followed by “boat and truck, helicopter, plane, balloon, and road” and “motorcycle” was the least correctly spelled word (19.05%). The most correctly spelled word by both groups was “car” with a total of 157.14% and the least correctly spelled word by both groups was “road” with a total of 61.91%. The experimental group outperformed the control group in all the words. The highest difference between the groups occurred in the spelling of the word “balloon” (42.86%) and the lowest difference between the groups occurred in the spelling of the word “car” (4.76%).

Table 8 demonstrates “Unit 9 - Weather” dictated target vocabulary correct spelling percentages and percentage difference between groups. The target word “hot” was the most correctly spelled word by the experimental group (85.71%) followed by “foggy, windy, rainy-snowy and sunny”, the word “cool” was the least correctly spelled words (57.14%). The control group, also spelled the word “hot” most correctly (80.95%) followed by “foggy, snowy, cool, sunny, windy” and “rainy” was the least correctly spelled word (23.81%). The most correctly spelled word by both groups was “hot” with a total of 166.66% and the least correctly spelled word by both groups was “rainy” with a total of 85.71%. The experimental group outperformed the control group in all the words. The highest difference between the groups occurred in the spelling of the word “rainy” (38.09%) and the lowest difference between the groups occurred in the spelling of the word “hot” (4.76%).

The primary aim of this study was to find out whether games affected the writing skills of primary school 3rd grade EFL learners. With this main query in hand, this study sought to find out whether any differences would exist between the experimental and control group in regards to participants’ success rates and the participants’ target vocabulary correctness rates in the Dictation Exercise. The findings, as they were discussed earlier, demonstrated that the experimental group outperformed the control group on the grounds of overall and total correct spelling by %19.36, thus we may argue that games help to the development of the writing skills of young EFL learners. Success rates on the grounds of a unit-based evaluation also demonstrated that the experimental group outperformed the control group in every unit. Taken together, both groups best performance was in Unit 9 (113.59%), followed by Unit 6 (108.26%), Unit 8 (105.95%) and Unit 7 (102.71%).

Therefore, it is recommended that Turkish primary school English language teachers use games in the development of their students’ writing skills. Furthermore, the findings of this research also revealed that the participants in this study were better in correctly writing some of the target vocabulary, that was the focus of this study, than others. To this end, Table 9 reveals the best and worst spelled vocabulary by the two groups in this study. Table 10, on the other hand, reveals the best and worst spelled vocabulary in this study, regardless of the groups. Thus, it is believed by the author that it is a more inclusive and general finding.

As a final word, the findings of this study and the findings revealed in Tables 9 and 10 may serve as a reference and may be of help to Turkish primary school English language teachers during their teaching, practice and planning of any spelling activities. They may, for example, want to do more practice on the worst spelled vocabulary in each unit. A further phonological analysis of the best and worst spelled vocabulary should be the topic for further research.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Besner D, Smith MC (1992). Basic processes in reading: Is the orthographic depth hypothesis sinking?.In R Foster, L. Katz (Eds.), Orthography, phonology, morphology, and meaning (45-66). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Cave S (2006). Practicing Modern Foreign Languages in the Primary classroom. Dorset: Brilliant Publications.

|

|

|

|

|

DaÄŸlıoÄŸlu Ö (2015). English 3. BilenYayınları.

|

|

|

|

|

DurgunoÄŸlu AY (2006). How the language's characteristics influence Turkish literacy development. In M Joshi, PG Aaron (Eds). Handbook of orthography and literacy. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum Associates.

|

|

|

|

|

Ersöz A (2007). Teaching English to Young Learners. Ankara: KozanOfset.

|

|

|

|

|

Hannell G (2008). Spotlight on spelling: A teacher's toolkit of instant spelling activities.

|

|

|

|

|

Katz L, Frost R (1992). The reading process is different for different orthographies: The orthographic depth hypothesis. In: R Foster, L. Katz (Eds.), Orthography, phonology, morphology, and meaning (67-84). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kırkgöz Y (2010). An analysis of written errors of Turkish adult learners of English. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 2(1):4352-4358.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mattingly IG (1992). Linguistic awareness and orthographic form. In R Foster, L. Katz (Eds.), Orthography, phonology, morphology, and meaning (11-26). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Miller RT (2019). English Orthography and Reading. The TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching, 1-7.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Montgomery D (2007). Spelling, handwriting and dyslexia: overcoming barriers to learning. New York: Routledge.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

MoNE (2018). 2018 Primary and secondary schools English lesson curriculum.

|

|

|

|

|

Roach P (2009). English phonetics and phonology: A practical course. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Rumley G (1999). Games and songs for teaching modern languages to young children. The teaching of modern foreign languages in the primary school, ed. P Driscoll, D. Frost, 114-25. London: Routledge.

|

|

|

|

|

Shankweiler D, Lundquist E (1992). On the relations between learning to spell and learning to read.In R Foster, L. Katz (Eds.), Orthography, phonology, morphology, and meaning (179-192). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Wright W (2010). Foundations for teaching English language learners: Research, theory, policy and practice. Philadelphia, PA: Caslon.

|

|

|

|

|

Yolageldili G, Arikan A (2011). Effectiveness of Using Games in Teaching Grammar to Young Learners. Elementary Education Online 10(1):219-229.

|

|

|

|

|

Yule G (2014). The study of language, (5th ed.) Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

|

|