Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

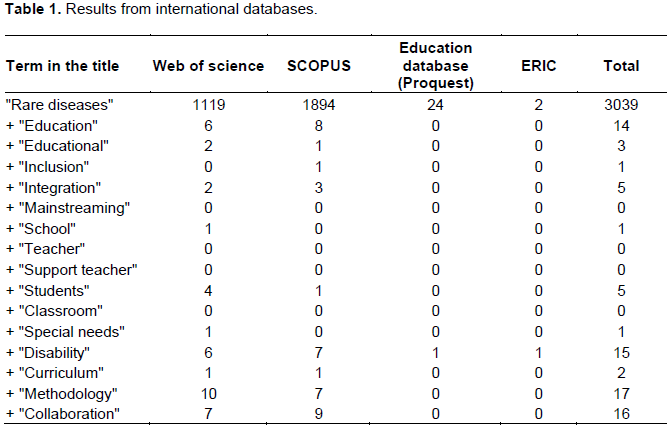

Rare diseases (RDs) represent a wide, varied group of illnesses characterised by their low prevalence among the population. Moreover, they can appear at any time of life, including in infancy. For this reason, the aim of this article was to review and analyse research in the field of education to find out what kind of educational response is offered by schools to pupils with RDs. The following databases were used to find the pertinent bibliography: Web of Science, Scopus, Education Database (Proquest) and Eric. After retrieving the publications included in this study, each paper was reviewed and analysed on the basis of what journal they were published in and their abstracts. Out of the 53 studies included, only six bore any relation to the school context. The results showed that while there are scientific papers on RDs, most of them are restricted to the medical sphere. It was therefore concluded that further research is needed in the field of education to advance in the schooling of pupils with RDs.

Key words: Rare diseases, inclusive education, school, systematic review.

INTRODUCTION

METHODOLOGY

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

CONCLUSIONS

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

REFERENCES

|

Alkhateeb JM, Hadidi MS, Alkhateeb AJ (2016). Inclusion of children with developmental disabilities in Arab countries: A review of the research literature from 1990 to 2014. Res Dev Disabil, 49-50:60-75. |

|

|

Andersen T, Le Cam Y, Weinman A (2014). European reference networks for rare diseases: The vision of patients. Blood Transfus, 12:S626-S627. |

|

|

Ayme S, Rodwell C (2014). The European union committee of experts on rare diseases: Three productive years at the service of the rare disease community. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 9:30. |

|

|

Ayme S, Bellet B, Rath A (2015). Rare diseases in ICD11: Making rare diseases visible in health information systems through appropriate coding. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 10:35. |

|

|

Barrio JA, Castro A (2008). Infrastructure and resources of social, educational and health support in rare diseases. An Sist Sanit Navar, 31:153-163. |

|

|

Begeny JC, Martens BK (2007). Inclusionary education in italy - A literature review and call for more empirical research. Rem. Spec. Educ. 28(2):80-94. |

|

|

Brouard-Lapointe A, Moutel G, Gimenes P (2015). Rare diseases and patient organization collaboration in the medical research: Analysis of the issues with all the protagonists. Mol. Genet. Metab. 114(2):S25-S25. |

|

|

Bryant DP, Smith DD, Bryant BR (2008). Teaching Students with Special Needs in Inclusive Classrooms. Boston, MA: Pearson Education, Inc. |

|

|

Budych K, Helms TM, Schultz C (2012). How do patients with rare diseases experience the medical encounter? exploring role behavior and its impact on patient-physician interaction. Health Policy 105(2):154-164. |

|

|

Chisolm S, Salkeld E, Houk A, Huber J (2014). Partnering in medical education: Rare disease organizations bring experts and a patient voice to the conversation. Expert Opin. Orphan D. 2(11):1171-1174. |

|

|

Cismondi I, Kohan R, Adams H, Bond M, Brown R, Cooper JD, Noher de Halac I (2015). Guidelines for incorporating scientific knowledge and practice on rare diseases into higher education: Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses as a model disorder. Bba-Mol. Basis Dis. 1852(10):2316-2323. |

|

|

Clarke JTR, Coyle D, Evans G, Martin J, Winquist E (2014). Toward a functional definition of a "rare disease" for regulatory authorities and funding agencies. Value Health, 17(8):757-761. |

|

|

Cui Y, Han J (2015). A proposed definition of rare diseases for china: From the perspective of return on investment in new orphan drugs. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 10:28. |

|

|

Demetriou Y, Sudeck G, Thiel A, Hoener O (2015). The effects of school-based physical activity interventions on students' health-related fitness knowledge: A systematic review. Educ. Res. Rev-Neth. 16:19-40. |

|

|

Dragusin R, Petcu P, Lioma C, Larsen B, Jorgensen HL, Cox IJ, Winther O (2013). FindZebra: A search engine for rare diseases. Int. J. Med. Inform. 82(6):528-538. |

|

|

Facey K, Hansen HP (2015). The imperative for patient-centred research to develop better quality services in rare diseases. Patient, 8(1):1-3. |

|

|

Facey K, Granados A, Guyatt G, Kent A, Shah N, van der Wilt GJ, Wong-Rieger D (2014). Generating health technology assessment evidence for rare diseases. Int. J. Technol. Assess 30(4):416-422. |

|

|

Fagnan DE, Yang NN, McKew JC, Lo AW (2015). Financing translation: Analysis of the NCATS rare-diseases portfolio. Sci. Transl. Med. 7(276):276ps3. |

|

|

Fedyaeva VK, Omelyanovsky VV, Rebrova O, Khan N, Petrovskaya EV (2014). Mcda approach to ranking rare diseases in russia: Preliminary results. Value Health 17(7):A539-A539. |

|

|

Fioravanti C (2014). Rare diseases receive more attention in Brazil. Lancet 384(9945):736-736. |

|

|

García M (2013). The diagnosis of rare diseases in the primary care clinic: Dismantling the myth. Aten Prim, 45(7):338-340. |

|

|

Groft SC (2013). Rare diseases research expanding collaborative translational research opportunities. Chest 144(1):16-23. |

|

|

Groft SC, Rubinstein YR (2013). New and evolving rare diseases research programs at the national institutes of health. Public Health Genom. 16(6):259-267. |

|

|

Han KG (2008). A study on the characteristics and educational support for children with rare diseases. Korean J. Phys. Multiple Health Disabil. 51(3):1-18. |

|

|

Jinnah HA (2011). Needles in haystacks: The challenges of rare diseases. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 53(1):6-7. |

|

|

Kesselheim AS, McGraw S, Thompson L, O'Keefe K, Gagne JJ (2015). Development and use of new therapeutics for rare diseases: Views from patients, caregivers, and advocates. Patient 8(1):75-84. |

|

|

Kirby T (2012). Australia makes up for lost time on rare diseases. Lancet 379(9827):1689-1690. |

|

|

Kovács L, Hegyi E, Nagyová G (2013). Orphanet - information, education and expert centres for rare diseases. Acta Facultatis Pharmaceuticae Universitatis Comenianae, 60(SUPPL. 8):10-15. |

|

|

Lee HH, Lee KM (2014). Students diagnosed with congenital vascular malformation as a form of rare diseases and their parents' experiences and needs. J. Spec. Educ. 21(2):26 |

|

|

Lin J, Lin L, Hung W (2013). Reported numbers of patients with rare diseases based on ten-year longitudinal national disability registries in Taiwan. Res. Dev. Disabil. 34(1):133-138. |

|

|

Luzzatto L, Hollak CEM, Cox TM, Schieppati A, Licht C, Kaariainen H, Remuzzi, G (2015). Rare diseases and effective treatments: Are we delivering? Lancet 385(9970):750-752. |

|

|

Mavris M, Dunkle M (2014). Working collaboratively and internationally to improve the lives of people affected by rare disease. Expert Opin. Orphan. D. 2(11):1117-1121. |

|

|

McLeskey JY, Waldron NL (2002). School change and inclusive schools: Lessons learned from practice. Phi Delta Kappan, 84(1):65. |

|

|

Moliner AM, Waligora J (2013). The European union policy in the field of rare diseases. Public Health Genom. 16(6):268-277. |

|

|

Rabeharisoa V, Callon M, Filipe AM, Nunes JA, Paterson F, Vergnaud F (2014). From 'politics of numbers' to 'politics of singularisation': Patients' activism and engagement in research on rare diseases in france and portugal. Biosocieties 9(2):194-217. |

|

|

Ramalle E, Ruiz E, Quinones C, Andres S, Iruzubieta J, Gil J (2015). General knowledge and opinion of future health care and non-health care professionals on rare diseases. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 21(2):198-201. |

|

|

Rose R (2002). The curriculum: A vehicle for inclusion or a lever for exclusion?. In C. Tilstone, Florian L, Rose R (Eds.), Promoting inclusive practice (pp. 27-38). London, UK/ New York, NY: Routledge Falmer. |

|

|

Schieppati A, Henter J, Daina E, Aperia A (2008). Why rare diseases are an important medical and social issue. Lancet 371(9629):2039-2041. |

|

|

Schultz C, Schreyoegg J, Stargardt T (2012). Focus on designing health care structures and services for rare diseases. Health Policy 105(2-3):107-109. |

|

|

Schumacher KR, Stringer KA, Donohue JE, Yu S, Shaver A, Caruthers RL, Russell MW (2014). Social media methods for studying rare diseases. Pediatrics 133(5):E1345-E1353. |

|

|

Scott BJ, Vitale MR, Masten WG (1998). Implementing instructional adaptations for students with disabilities in inclusive classrooms. A literature review. Rem. Spec. Educ. 19(2):106-119. |

|

|

Silibello G, Vizziello P, Gallucci M, Selicorni A, Milani D, Ajmone PF, Lalatta F (2016). Daily life changes and adaptations investigated in 154 families with a child suffering from a rare disability at a public centre for rare diseases in northern Italy. Ital. J. Pediatr. 42:76. |

|

|

Smith CT, Williamson PR, Beresford MW (2014). Methodology of clinical trials for rare diseases. Best Pract. Res. Cl. Rh. 28(2):247-262. |

|

|

Tambuyzer E (2010). Rare diseases, orphan drugs and their regulation: questions and misconceptions. Nature Review, Drug discov. 9:921-929. |

|

|

Taruscio D, Capozzoli F, Frank C (2011). Rare diseases and orphan drugs. Ann Super Sanita 47(1):83-93. |

|

|

Taruscio D, Agresta L, Amato A, Bernardo G, Bernardo L, Braguti F, Vittozzi L (2014a). The Italian national centre for rare diseases: Where research and public health translate into action. Blood Transfus, 12:S591-S605. |

|

|

Taruscio D, Gentile AE, Evangelista T, Frazzica RG, Bushby K, Montserrat AM (2014b). Centres of expertise and European reference networks: Key issues in the field of rare diseases. the EUCERD recommendations. Blood Transfus. 12:S621-S625. |

|

|

Torrente E, Martí T, Escarrabill J (2010). Impacto de las redes sociales de pacientes en la práctica asistencial. Revista de Innovación Sanitaria y Atención Integrada 2(1):1- 8. |

|

|

Van Karnebeek CDM, Houben RFA, Lafek M, Giannasi W, Stockler S (2012). The treatable intellectual disability APP www.treatable-id.org: A digital tool to enhance diagnosis & care for rare diseases. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 7:47. |

|

|

Von der Schulenburg JG, Frank M (2015). Rare is frequent and frequent is costly: Rare diseases as a challenge for health care systems. Eur. J. Health Econ. 16(2):113-118. |

|

|

Waldman HB, Perlman SP, Munter BL, Chaudhry RA (2008). Not so rare, rare diseases. The Except. Parent 38:46-47. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0