Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

In 2007, some curricular changes of teacher training system were initiated in Mozambique with teacher training course model 10+1. The changes included the teaching of English together with other new subjects that required the training of teachers capable of implementing them to meet the needs of primary education curriculum. In order to examine the implementation of the curricular changes in primary teachers’ institutes, an in-depth study was conducted with attention paid to the integration of complementary subjects for English course at Chicuque teacher-training institute, using a qualitative study. Data were collected through in-depth interviews and document analysis. During the fieldwork, qualitative data were initially analysed through manual methods of coding, clustering and summarizing. At the later phase, electronic methods were used for data processing in Word and Excel software. The personnel’s qualifications, specialization and position were used as the criteria for inclusion of 37 participants involved in curriculum design, Education management and teachers of English in primary schools based on a non-probability and purposive sampling technique. The results indicated that curricular change in study has never been implemented owing to the flaw found in the policy formulation. This article claims that if the curriculum itself is designed with omissions of key guidelines, it will be unlikely to have an effective implementation and suggests a deep evaluation of teacher training policies to review the study plan of the English Course for primary education.

Key words: Teacher training, curricular changes, implementation, policy formulation.

INTRODUCTION

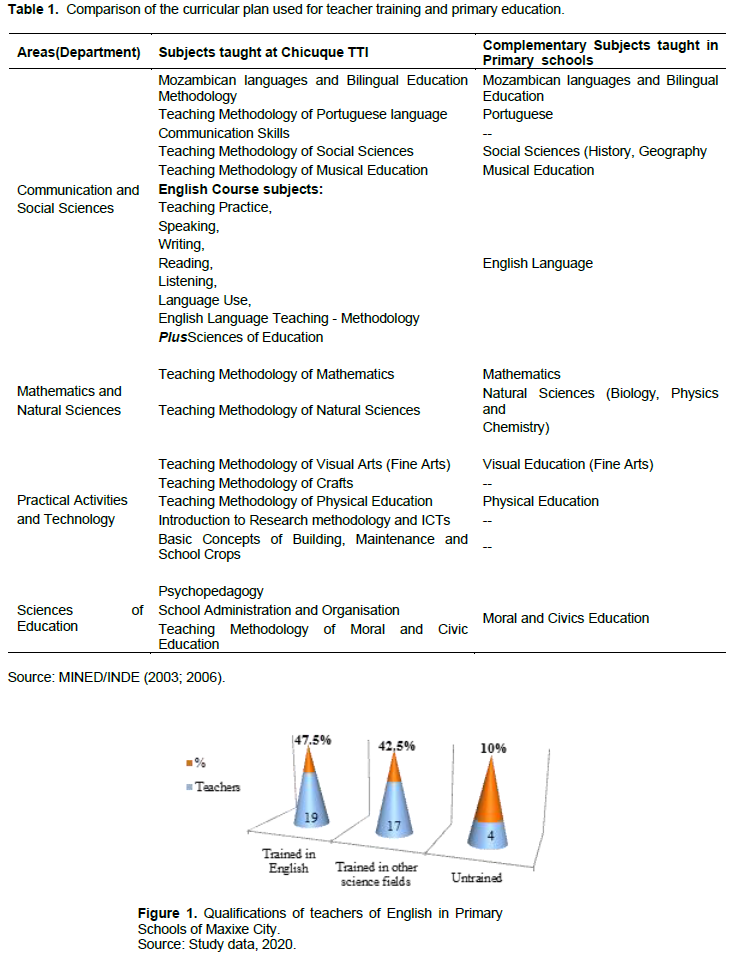

The educational system in Mozambique comprises six educational subsystems out of which the teacher training is the fifth subsystem as listed in Art. 9 of Law 18/2018 of December 28. The teacher training for basic education takes place at the Teacher Training Institutes, which are divided into two categories: state institutes called IFPs and private colleges called EFPs, but both run the same training curriculum delivered and monitored by the Ministry of Education as the central body. Since 1975, when Mozambique became independent from colonial system, the teacher training policies and practices have changed along the time and a few studies have shown that the training models change overtime alongside with the curricular reforms (Passos, 2009; Matavele, 2016; Carita et al., 2017). Thus, in 2007 a new one-year training model was introduced in order to meet the needs of English teaching within the new curriculum for basic education (MINED, 2006) and the potential candidates were those students who finished grade 10 of general secondary education (Decree 41/2007 of May 16), hence it is commonly shorthanded as model 10+1. This study is mainly concerned with the implementation of the curricular changes in primary teachers’ institutes focusing on the realisation of complementary subjects for English course at Chicuque teacher training institute (CTTI),as one out of nineteen state institutes where the training course model 10+1 is still in force (MINED, 2018). The change consisted of a set of about five proposed subjects to be integrated in the English course training (Table 1). The curricular change under study was proposed in the training syllabus designed by the National Institute of Education Development (INDE) under the Ministry of Education. It was formed in a top-down or centralized perspective by the government policy-planning organization, giving it a form of mandatory implementation instrument to the training institutes.The top-down approach adopted for designing the teacher training syllabus seems to be appropriate since in Mozambique there is a single public agency responsible for designing educational programs for teacher education (Sabatier, 1986).

For Wolman (1981), policy formulation process starts with the conceptualization of the problem by policymakers. Thus, the need of trained teachers for English teaching in primary schools was the problem identified before the formulation of the new curriculum for basic education introduced in 2004, which comprised English as new school subject to be taught from grade 6 (MINED, 2003). Then, the policymakers conceived the course model 10+1 as policy response that could in short term deliver higher number of graduates into Education system. The implementation of new educational policy depends mainly on how teachers as implementers are prepared to put it into practice (Chaudhary, 2015). That is, if teachers lack appropriate training on complementary subjects for English course, the implementation of the proposed subjects will be unlikely to take effect. This article seeks to share the findings of a qualitative study conducted in the scope of curriculum implementation. The study aimed to examine the implementation of curricular changes in primary teachers’ institutes focusing on the materialisation of the policy of integrating complementary subjects in the English course model 10+1 at Chicuque teachers’ institute in Inhambane Province. As defined by the central body, the major purpose of the curricular change was to equip the graduates of English course with teaching methodologies of other subjects along with English since they are expected to teach the proposed subjects as required by the primary education curriculum. Curriculum implementation is one of the phases of the entire curriculum development process (Roselli, 2005). It is the operational phase where the political decisions in form of teacher training syllabus are realized. Therefore, it has been expected that at implementation stage the teacher trainers as implementers would put into practice the integration of complementary subjects for English course and quality control could be granted to provide an opportunity of making necessary adjustments to the training process; but through this study it could be found that neither the subject integration nor the quality control has been made. This reveals a gap in the implementation process owing to lack of clear guidelines on how the complementary subjects should be executed.

Available literature on policy implementation provides two theoretical traditions as foundation to this study, namely the Top-down and Bottom-up approaches represented by scholars like Van Meter and Van Horn (1975), Nakamura and Smallwood (1980), Mazmanian and Sabatier (1983) cited in (Guro, 2009). The top-down corresponds to centralized power (authority) and bottom-up corresponds to the decentralized power (democratic). In this perspective, Fullan (2012) highlights the flaw of centralization in its side of over control and decentralization for being prone to chaos. In the same vein, Pulzl and Treib (2006) state that Top-down models put their main emphasis on the ability of decision makers to produce unequivocal policy objectives and on controlling the implementation stage. Bottom-up critiques view local bureaucrats as the main actors in policy delivery and conceive implementation as a negotiation process within networks of implementers (pp. 2-3).

Furthermore, scholars point out that implementation and policy formulation are inter-dependent processes (Pulzl and Treib, 2006). Jansen (2003) quoted by Guro (2009) adds that “the relationship between policy and practice is not a linear, rational and predictable process” (p.23). Thus, the present study finds its theoretical support in this view point because the way the training curriculum is implemented at bottom level (teachers’ institutes) is dependent on how that policy instrument has been designed by the top authority. Even though the actual teacher trainers’ experiences qualifications and indicators of academic ability or subject-matter knowledge appeared to be good enough for their job, they do not know how to effectively integrate the complementary subjects since the course syllabus (policy) provided no strategies of how the complementary subjects should be executed and this seemed to be the critical design flaw. This study was guided by two major questions: How do primary teachers’ institutes implement the policy of integrating complementary subjects in the English course? How can the policy implementation impact the teaching practices in primary schools? By taking a qualitative study approach, it was hoped that an in-depth understanding could be gained of how specialists of curriculum design, education managers and teachers of English in primary schools perceived their work experiences in connection with the implementation of curricular changes in teachers’ institutes for primaryeducation. This study can be considered of great relevance since its outcomes can provide the body of policymaking with an indication of what could be improved in the formulation of teacher training policies with particular reference to training teachers of English for primary education in Mozambique. Besides, it also updates information on teacher training in Mozambique such as the effectiveness of the cyclical curricular reforms, which have been reported in the previous studies conducted by scholars like Matavele (2016), Carita et al. (2017), Beutel et al. (2011), Guro (2009), Passos (2009) and Mucavele (2008). A few of these studies have made an accurate diagnosis of problems in the implementation of teacher training policy, but none have explored the factors behind the non-integration of complementary subjects into English course and its impact on the quality of education. Moreover, this study pays special attention to the training model 10+1 which delivers higher number of graduates estimated in 4644 applicants trained in 19 teachers’ institutes (MINED, 2017) than 942 from the concurrent model 10+3.

A conceptual background is herein provided with the discussion of the key concepts of this study, namely; the teacher training in Mozambique, curricular changes in teacher training system and curriculum implementation as follows: Teacher training is defined by Mozambique’s Law 18/2018 of December 28 (Art.16) as a subsystem of education aimed at: ensuring an integral training of teachers, enabling them to hold responsibility of educators and train children, youth and adults; conferring teachers, a consistent general scientific training, psycho-pedagogical, methodological, ethical and deontological training; and offering a training that stimulates a reflexive, critical and active conduct in accordance with the social reality. An overview of the beginning and evolution of teacher training policies and practices in Mozambique since 1975 has been made in three previous studies by Passos (2009), Matavele (2016) and Carita et al. (2017). Therefore, this article is not intended to trace back all the curriculum changes made in teacher training, but it highlights the changes since the national independence in 1975, Mozambique has experimented over 21 different teacher training ‘models’ without reaching an ideal model (Beutel et al., 2011). Guro (2009) added that “the change from one training model to another has not had a follow-up or a thorough evaluation to determine the strengths and weaknesses of the previous models” (p.6). These remain true until today, because since 2018, two models of teacher training have taken place simultaneously; one model with one-year duration and another one with three years (MINED, 2018). This study is interested in the earlier model 10+1 introduced in 2007.

Regarding the curriculum changes, Passos (2009) points out “two common reasons in teacher education. One is the need to conform to political changes and another is the need to improve the quality of teaching” (p.33). Passos further explains that in 1975, changes were introduced in Mozambique to adjust to new policies and goals in education, but in recent years, the main reason for change has been to improve the quality of education. The current legal framework of teacher training is established under the Law 18/2018 of December 28, which establishes that training for all education subsystems will thereafter be imparted in specialized institutions, and defines the general goals for this training as follows: to integrally train teachers, providing them with solid scientific, psycho-pedagogical and methodological skills as well as the ability to continuously develop them. The Law 18/2018 of December 28 defines six levels of teacher training, to wit: for pre-school, for primary education, for secondary education, for technical and professional education, for adult education and for higher education. Each of these levels has its training institution, access requirements and the target degree to teach. However, the focus of this study is on the second level for primary education with much attention on the initial training model 10+1 rather than in-service and continuing training. The initial teacher education has a major part to play in the making of a teacher because it marks the initiation of the novice entrant to the calling and as such has tremendous potential to imbue the would-be teacher with the aspirations, knowledge-base, repertoire of pedagogic capacities and human attitudes (Kumar, Chapter 6 in Manichander, 2016). Effectively, teacher performance is a major factor in school success and a good performance of the teacher depends to a large extent on his training whereby the most important part “of the entire process of teacher education lies in its curriculum, design, structure, organization and transaction modes, as well as the extent of its appropriateness” (Kumar, Chapter 6, in Manichander, 2016, p.152). This is where the phenomenon in study was identified, that is, the implementation of the English course guidelines was brought into question because its design and structure appeared not articulated.

The term ‘curricular change’ will be used in this article as interchangeable with curricular innovations, curricular reforms or curricular development, which is defined as planned, a purposeful, progressive, and systematic process of creating positive improvements in the educational system (Alvior, 2014). When changes or developments happen around the world, the school curricula are affected, hence there is a need to update them to address the current society’s needs. Curricular reforms are not new and occur worldwide. So, in 2004, the new basic education curriculum was introduced in Mozambique (MINED, 2003), comprising new subjects including English for the 3rd cycle of primary education and required trained teachers of English and other new subjects. Because of the innovation in primary education curriculum, the teacher training curriculum in Mozambique had to be adjusted to this new reality, and in 2007 a new training model 10+1 was introduced, consisting of two optional courses: regular course and English course with complementary subjects such as Crafts, Musical Education and Visual Arts (MEC, 2006). Each of these courses consists of several compulsory training subjects which trainees are required to complete for graduation. This study aimed to examine how the curricular innovation of integrating complementary subjects in English course of teacher training has been implemented and the reason why it has been implemented in that way. It also attempted to identify its possible effect on the teaching practices in primary schools in accordance with the new curriculum of basic education.

Curriculum implementation refers to the stage when the curriculum itself, as an educational programme, is put into effect. Kumar (2016) and Chaudhary (2015) explain that the term “entails putting into practice the officially prescribed courses of study, syllabuses and subjects” (p.984). It consists of putting into practice an ideal programme or set of new activities and structures for the people expected to change (Fullan and Stiegelbauer, 1991). In other words, policy implementation is a process whereby people put in practice the norms, regulations, policy and decisions taken by policymakers. In Mozambique, the main strategies to implement the new curriculum for basic education are teacher training, teachers’ upgrading and the expansion of primary schools. This study is concerned with the implementation of the policy changes designed for teacher training model 10+1, mainly for the English course because research has shown that “innovations are seldom implemented in the classroom in exactly the same way developers had intended” (Elmore and Sykes, 1992, p.42). The realisation of curriculum implementation depends on a number of factors that influence a successful implementation. Chaudhary (2015) puts forward the following factors: resource materials and facilities, the teacher, the school environment, culture and ideology, instructional supervision and assessment. One more element could be added to the range of factors above listed and that is ‘curriculum formulation’ because if the curriculum document is flawed in its design, it will be unlikely to have an effective implementation. This belief is supported by Guro (2009) and Malen and Knapp (1997) when they state that in general, failure of policy implementation is due to badly designed policy which is also influenced by economic and political reasons in developing countries.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Two methods were used for data collection in this study: one was in-depth interview to gather primary data and another was documentary analysis seeking secondary data from government publications. Despite the limitations of in-depth interviews as pointed out by Kothari (2004), this method was adopted for its merits and flexibility, and, more importantly, being this a small-scale study, individual interviews were conducted with a small number of respondents to explore their experiences, perceptions and the thoughts they have on the implementation of the curricular change proposed to integrating complementary subjects in the English course delivered in teacher training institutes. It allowed the author to get large amounts of data for later interpretation as “the theoretical roots of in-depth interviewing are in what is known as the interpretive tradition” (Kumar, 2011, p.151). In addition, documentary analysis was used when access to informants was denied at the National Institute of Education Development (INDE) and at Education inspectorate in Inhambane respectively. Johnson (1984) further states that “the lack of access to research subjects may be frustrating, but documentary analysis of files and records proved to be a valuable alternative source of data for the study” (p.23). Thus, key documents such as the teacher training syllabus and primary education programme were asked from senior officials of Education and both were designed by the INDE under the Ministry of Education. This study was carried out in the first term of 2020 at Chicuque Teacher Training Institute (CTTI) sampled from a pool of 19 teachers’ state institutes (MINED, 2018) which follow the same course model 10+1. The site selection was based on a judgemental or purposive sampling technique within a non-probability sampling design (Martella, et al., 2013 cited in Molapo and Pillay, 2018). The first reason for choosing this study site was the fact that the CTTI is the author’s work place and as local teacher trainer he wanted to find out why the training policy seemed to be unaligned with classroom practice. The second reason was the belief that the homogeneous features of the training curriculum used at CTTI could provide commonalities and patterns of the occurrence of the phenomenon in other institutes running the same training course model. According to Daniel (2012) purposive sampling of population is done on the basis of their fit with the purposes of the study and specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Thus, the selection criteria used in this study for interviewing informants were people’s qualifications, specialization and position they hold in the assumption that these traits aggregate value to their acquaintance with the central phenomenon. A few procedures were followed for this study to be accomplished: first, the submission of permission letter and the research credential gave room for the accomplishment of this study, to have access to the study sites, approach the study population and set an interview schedule with 37 participants including two specialists of curriculum design working at the National Institute of Education Development, five heads of departments in Education management working at the National Directorate of Teacher Training, at Provincial Directorate of Education and Human Development, at four District Offices of Education, Youth and Technology, at CTTI and 30 teachers of English in primary schools in Inhambane Province. The data confirmation, approval, validation and accuracy were ensured by transcription of interviews which were then shared with participants. Since this study aimed to examine the procedures of curriculum implementation process, the data analysis was made within interpretive framework of analysis (Kumar,2011) in which qualitative data expressed in words, descriptions, accounts, opinions and feelings were converted through coding, clustering and summarizing to make analysis (Miles and Huberman, 1994). The process of data analysis was made through manual coding of qualitative data (Lofland, 1971; Bogdan and Bilken, 1982) for both in-depth interviews and documentary analysis since this was a small-scale study (Bell, 2005) and then processed in Word and Excel software.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The principal aim of this study was to examine the implementation of the curricular changes in primary teachers’ institutes, focusing on the integration of complementary subjects for English course at Chicuque teacher-training institute. Research has demonstrated that various factors play a role in the effective implementation of curricular changes (policy). Alghazo (2015) presents first, factors related to the teaching process such as instructional materials and strategies, teachers’ expertise and their training in this area as well as the teaching approaches. Second, factors related to the learning process such as individual differences of learners, their linguistic and educational backgrounds, their expectations, their use of language learning strategies, and above all their motivation to learn, to mention just a few. Third and last, but not least, contextual factors such as institutional constraints and policies also play a great role in this regard. Institutional variables include the curriculum structure and design, the choice of teaching materials, the timing of lectures and the availability of instructional aids and facilities that teachers can make use of in their teaching. This study is concerned with the last type of institutional factors (that is the curriculum structure and design) that affect how the training of primary school teachers takes place in the TTI. The data analysis yielded the findings in alignment with the major themes that can be inferred from the study questions.

Curriculum implementation

It was found that the teacher training institute of Chicuque has not implemented the curricular change of integrating complementary subjects into the English course and the reason behind the implementation failure is the error found in the curriculum formulation, that is, the planning agency designed the Curricular Plan of Teacher Training for Primary Education which integrates the study plan of English course. Within the curricular plan it is proposed that the English course training should integrate complementary subjects whose language of instruction is Portuguese to enable the future teachers of English to also teach these subject in primary schools where a single teacher deals with all the subjects of a certain grade including English from grade 6 onward. However, the same planning body did not put forward the integration mechanism possibly by creating an appropriate slot in the study plan. This omission is regarded in this study as the critical flaw which made the proposal of complementary subjects to fail in its implementation because it had no implementation strategy. This applies to eighteen more teachers’ institutes that follow the same training model 10+1.

This finding could be regarded as a response to the gap of knowledge found in previous studies on how the teacher training institutes implemented the curriculum changes by giving no attention to the policy of English course. Guro (2009) explored the relationship between policy and practice like the present study; his research aimed to determine how the learner-centred approach and interdisciplinary approach was implemented in one of teacher training institute, but no attention was given to the implementation of the new subjects including English, as the interest of the present study. Another study carried out in 2008 by Mucavele discussed the phenomenon of curriculum implementation, which is also tackled in this manuscript. However, while the previous study aimed to examine the implementation process of the new basic education curriculum in Mozambique in order to ascertain how the intended curriculum changes were being operationalized, the present study aims to examine the implementation process of the teacher training curriculum in attempt to find out whether or not the policy of integrating complementary subjects in the English course is implemented, and then ascertain the associated factors. The correlation between the two studies is that, one investigates the curriculum implementation in the downstream of Education system (bottom up approach) and the other examines the same phenomenon in the upstream (top down approach) and both studies are concerned with the effect of curriculum changes in the primary education for achievement of the goal of improving Education quality in Mozambique.

Impact of curriculum implementation

The study showed that the curricular change examined has not been implemented and the graduates finish their training without the required competence to teach the proposed subjects. This may reveal that the issue of ‘competence to teach’ is put at stake as Medley and Shannon (1994) highlight that a competent teacher should possess two kinds of knowledge, knowledge of subject matter and professional knowledge, and training programmes are developed to help students become competent in this sense. Thus, the effect of the error found in the policy formulation on implementation process is that, since the policy designer (central authority) did not predict the implementation strategy or a mechanism of how the innovation of complementary subjects should be executed, as a result, the intended innovation was not realised by the downstream implementers.

Lack of coherent training policy

It was found that the curricular plan for English course is not aligned with its course plan and the teaching programme in primary schools. Research had reported the lack of a coherent teacher training policy in Mozambique and this finding came to confirm the phenomenon.

Curriculum formulation

The study discovered that the curricular plan (syllabus) for English course contains an error in its formulation. The discovery came to light during the documentary analysis of the curricular plan for basic education and teacher training curriculum. One of the official documents analysed in this study is the Curricular Plan of Teacher Training for Primary Education which integrates the Study Plan of English course. The plan covers four departments namely: Communication and Social Sciences; Mathematics and Natural Sciences; Practical Activities and Technology and Educational Sciences as detailed in Table 1. A thorough reading of this document shows that the Study Plan of the English Course has no slot to integrate the complementary subjects of Block 3 which are proposed in the same document as curricular innovation, except four other subjects whose medium of instruction is Portuguese namely; the Teaching Methodologies of Moral and Civic Education, Mozambican languages, Psychopedagy and School Administration and Organisation. These subjects are delivered in the first term of the course not as integrated part of the curricular innovation. In other words, the complementary subjects that were proposed intending to meet the primary school needs are given no room during the training in favour of other subjects that are regarded as minor in the English course all in accordance with the design of the training curricular plan. From the context described above, it can be perceived that the issue of complementary subjects was only proposed in the policy design by the policymaker (INDE), but the same entity did not suggest the integration mechanism possibly by creating an appropriate slot in the Study Plan. As a result, the curricular innovation is deemed as failure of policy formulation which poses great challenges to the new generation of teachers who take the training model of 10+1 because they finish their training with a gap of knowledge of the teaching methods for the subjects they are directed to teach soon they graduate in a clear incoherence of the training policy and teaching practice in primary schools. The policy incoherence is depicted in a top-down comparative analysis between the curricular plan of teacher training and curricular plan for Basic Education in Primary schools (Table1) to see if they match one another. Through this comparison, it could be noticed that since the teachers of English are directed to teach every primary school subject, they are in fact, subject to teach without the required qualifications because the subjects listed for their training in English do not include every primary school subject. Chaudhary (2015) says there are various factors that influence curriculum implementation as presented in the introductory section above; however besides those factors, this study puts forward one more element of curriculum formulation, that is, if the curriculum design contains critical guideline omissions as described above, it may not have an effective implementation like the policy innovation investigated in this study. This standpoint is also supported by Malen and Knapp (1997) when they argue that in general, failure of policy implementation is due to badly designed policy influenced by economic and political reasons in developing countries.

Teachers’ qualifications

This study found that there are teachers with no training for teaching and other trained ones who teach subjects out of their training areas, as illustrated in Figure 1. Looking at both categories, the trained and untrained teachers become unskilled staff to teach complementary subjects together with English in primary schools because they had no previous exposure to the teaching methodology of those subjects. This is not new, in previous studies Craig et al. (1998) stated that:

In most developing countries, nations are forced to employ some under-qualified and often unqualified teachers in order to achieve universal primary education. This has generally been a major factor in the decline of the overall quality of education and the increase in recurrent budget expenditure. (p.6)

In connection with this finding, majority of teachers of English in primary schools perceive some challenges in their work experience marked by knowledge limitations on how to teach issues of Social Science, Musical Education, Mathematics, Portuguese, Physical Education as some of the subjects they are assigned to teach while their training in English course did not cover these subjects. These challenges could be regarded as an immediate effect of curriculum design leading to faulty implementation of teacher training policy, which in turn will negatively influence the learning quality.

Teachers’ placement

The study found that the placement of trained teachers in schools and their subject distribution do not always correspond with their training areas. This finding confirmed the report of a previous assessment of the Teacher Training Strategy 2004-2015 carried out by the MINED (2004), which revealed that there was lack of a national policy of teachers' placement according to their qualifications. As a result, the placement of teachers in primary schools tends to be an administrative procedure of the local Education authorities, which is only concerned with having the teaching staff in schools and gives no attention to the combination of qualifications, experience and teachers' inclinations with the specific needs of the schools where they are placed. This assertion is sustained with examples of primary teachers who did the regular course model 10+1 with no specialization in ELT, but they are assigned to teach subjects of block 3 including English. Similarly, there are teachers who have undertaken English course, but when they apply for the teaching post, they are oriented to teach either grades without English (from 1 to 5) or subjects which were not taught during their training.

Curriculum assessment

It was found that the training model 10+1 of English course has not been subjected to a formal assessment to measure its achievements. It is believed that a timely course assessment would contribute to identifying the training shortcomings and take the proper measures.

Remedial strategies

The study shows that some palliative solutions have been put in place to enhance the performance of untrained teachers and those lacking qualifications to teach complementary subjects and these include ‘knowledge sharing’ between novice teachers and experienced ones, peer-observations, group planning, capacity building sessions and the CPD and on-job training programmes. The government adopts these measures in acknowledgment of several challenges faced in the national educational system. This study also revealed that a new teacher training curriculum has been designed for applicants who finished grade 12 and it will have three-year duration to be in force from 2019 onward, which will cut the English course off from teachers’ institutes because the English subject will no longer be taught in primary schools, but rather from secondary schools up to universities.

CONCLUSION

It has been confirmed that the teachers’ institutes for primary education have not implemented the policy of complementary subjects in the same way as intended. This is due to some design flaw in the curriculum document. It is characterised by not providing strategies of how the complementary subjects should be executed. This led us to conclude that the relationship between policy and practice is not as linear and predictable as it may appear for the top authority. In this context, Hargreaves and Fink (2006) highlight that "change in education is easy to propose, hard to implement, and extraordinarily difficult to sustain"(p.6). Therefore, the evidence from this study showed that the practical application of the innovation of complementary subjects for English course at Chicuque teachers' institute remains a failure due to "lack of internal consistency within the curriculum design" (Van den Akker, 2010, p.178). Moreover, a previous study on teachers’ competence and its effect on pupils’ performance (Passos, 2009) reported that the lack of a coherent teacher training policy may somehow explain the low level of effectiveness of the education system. The present study corroborates with this assertion since it has revealed that the curricular plan of English course is not aligned with its course plan and the teaching programme in primary schools, and consequently the goals of the educational innovation of complementary subjects are prone to fall through. Since a large number of teachers from model 10+1 leave the institutes without the required pedagogical knowledge for teaching complementary subjects, some teaching limitations were reported by the teachers of English as part of their work experience, despite the implementation of remedial strategies by the government. Thus, it can be concluded that Mozambique faces problems related to teachers’ qualification as substantiated by evidence that there are qualified teachers assigned to work with subjects not connected with their training fields and other teachers with no training at all. The implication of non-implementation of complementary subjects for English course is that graduates finish their training without the required skills to teach the proposed subjects and afterward they hardly meet the teaching needs in primary schools where they are urged to teach complementary subjects together with English. As a result, it raises questions about the achievement of students’ learning in the hands of unskilled teachers. Scholars have reaffirmed that “the teacher quality is the main school-based predictor of students’ achievement (...) and the impact of many reforms of teacher policies depends on specific design features” (System Approach for Better Education Results [SABER], 2014, p.1). Thus, the flaw in policy design of complementary subject has made it ineffective in its implementation and impact. Despite the caveats of scholarly reports on the negative consequences of the coexistence of different teacher-training models on the quality of education (Passos, 2009; Beutel et al., 2011; Carita et al., 2017) and lack of formal assessment on the strengths and weaknesses amid the change from one model to another (Guro, 2009), it can be concluded that this phenomenon will still raise concerns for future studies. This is because this study showed that until 2018, the training model 10+1 had been in force, parallel to model 10+3 for seven years, and in the following year another training model 12+3 was in force.

RECOMMENDATIONS

This study has identified a few issues with implications on policy designing and it is hoped to give contributions to strengthen decision making in Mozambique’s education system particularly in teacher training subsystem. Its findings led to the following recommendations:

1. The Ministry of Education. The lack of a deep and thorough evaluation with a formal report on strength and weaknesses of the training model 10+1 makes it hard to measure the achievements of the curricular changes in teacher training subsystem. Therefore, the Ministry of Education should appoint a panel of experts to investigate the nature of the challenges and problems experienced in the implementation of the national curriculum of teacher training and propose long term guidelines which will be assessed from time to time.

2. The policymakers and curriculum designers. A timely review of the course plan of English course should be made for an effective integration of the complementary subjects since the graduates are called to respond to the teaching-learning needs in primary schools.

3. The Education managers. The training area of each teacher to be employed should be taken into account at recruitment for their school placement and subject distribution rather than placing them on the basis of administrative measures and schools’ needs of teaching staff.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Alghazo S (2015). The role of curriculum design and teaching materials in pronunciation learning. University of Jordan Amman. Research in Language 13(3). |

|

|

Alvior MG (2014). "The Meaning and Importance of Curriculum Development." Available at: |

|

|

Bell J (2005). Doing Your Research Project. (4th edition), London: Open University Press. |

|

|

Beutel M, Macicame A,Tinga R (2011). Teachers Talking: Primary teachers' contributions to the quality of education in Mozambique. London: VSO. |

|

|

Bogdan RC, Bilken SK (1982). Qualitative Research for Education: An Introduction to Theory and Methods. Boston, Mass. Allyn and Bacon. |

|

|

Carita A, Cau MM, Mofate OL, Duarte RS (2017). The Evolution of Teacher Training in Mozambique and the Contexts of its Emergence. [Chapter]. Available at: |

|

|

Chaudhary GK (2015). Factors affecting curriculum implementation for students. International Journal of Applied Research 1(12):984-986. |

|

|

Craig HJ, Kraft RJ, Du Plessis J (1998). Teacher Development: Making an impact. Washington: USAID. |

|

|

Daniel J (2012). Sampling essentials: Practical guidelines for making sampling choices. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. |

|

|

Elmore R, Sykes G (1992). Curriculum policy. In Jackson O (ed.). Handbook of research on curriculum. New York: Macmillan pp.185-215. |

|

|

Fullan M, Stiegelbauer S (1991). The New Meaning of Educational Change. (2nd edition). New York: Teachers College Press. |

|

|

Fullan M (2012). Change forces: Probing the depths of educational reform. Routledge. |

|

|

Guro MZ (2009). Basic Education Reform in Mozambique: The Policy of Curriculum Change and the Practices at Marrere Teachers College (Doctoral Thesis). Pretoria: University of Pretoria. Available at: |

|

|

Hargreaves A, Fink D (2006). Sustainable Leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass. |

|

|

Jansen JD (2003). What Education Schools write About Curriculum in Namibia and Zimbabwe? In Pinar WF (eds.), International Handbook of Curriculum Research. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. |

|

|

Johnson D (1984). 'Planning small-scale research'. In Bell J, Bush T, Fox A (eds.), Conducting Small-scale Investigations in Educational Management. London: Harper and Row, pp.191-210. |

|

|

Kothari CR (2004). Research Methodology: Methods and Techniques (2nd edition). New Delhi: New Age International (P) Limited. |

|

|

Kumar R (2011). Research Methodology: a step-by-step guide for beginners. (3rd edition) London: SAGE. |

|

|

Kumar AC (2016). Implementation of Curricula of Teacher Education. In Manichander T (Ed). Teacher Education. (2nd edition), India: Laxmi Book Publication, pp.150-155. |

|

|

Lofland J (1971). Analyzing Social Settings. Belmont, California. Wadsworth. |

|

|

Malen B, Knapp M (1977). Rethinking the multiple perspectives approach to education policy analysis: implications for policy-practice connections. Journal of Education Policy 12(5):519-545. |

|

|

Matavele HJ (2016). Training and professionalism: a study on the initial training of teachers of Basic Education in Mozambique (Doctoral dissertation, University of Aveiro (Portugal)). |

|

|

MEC (2006). Plano Curricular de Formação de Professores do Ensino Primário. Maputo: MINED. |

|

|

Miles MB, Huberman AM (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks: Sage. |

|

|

MINED (2003). Plano Curricular do Ensino Básico. Maputo: MINED. |

|

|

MINED (2017). EDITAL. Exames de Admissão às Instituições de Formação deProfessores para o Ensino Primário. Maputo: CNECE. |

|

|

MINED (2018). EDITAL. Exames de Admissão às Instituições de Formação deProfessores para o Ensino Primário. Maputo: CNECE. |

|

|

Molapo MR, Pillay V (2018). "Politicizing curriculum implementation: The case of primary schools." South African Journal of Education 38(1):1-7. |

|

|

Mucavele S (2008). Factors Influencing the Implementation of the New Basic Education Curriculum in Mozambican Schools. [Ph.D. Dissertation], Pretoria: University of Pretoria. Available at: |

|

|

Passos AFJ (2009). A Comparative Analysis of Teacher Competence and its Effect on Pupil Performance in Upper Primary Schools in Mozambique and SACMEQ Countries (Doctoral Thesis). Pretoria: University of Pretoria. |

|

|

Pulzl H, Treib O (2006). Policy implementation. In Fischer F, Miller GJ, Sidney MS (eds.) Handbook of Public Policy Analysis: Theory, Politics and Methods, Pp. 89-107; CRC Press, New York. |

|

|

Sabatier PA (1986). Top-down and Bottom-up Approaches to Implementation Research: A Critical Analysis and Suggested Synthesis. Journal of Public Policy 6(1):21-48. |

|

|

System Approach for Better Education Results (SABER) (2014). Teachers Mozambique Country Report. The World Bank. |

|

|

Van den Akker J (2010). Building bridges: how research may improve curriculum policies and classroom practices. In Stoney SM (ed.), Beyond Lisbon 2010: Perspective from research and development for educational policy in Europe. Sint-Katelijne-Waver, Belgium: CIDREE. pp.175-195. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0