Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

This paper carried out a contextual analysis of different models of performance appraisals in both developed and developing countries on Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). First, it conducted a thorough examination of the contextual implications of performance appraisal models in developed and developing countries. Secondly, to better understand the various performance appraisal models for HEIs in both developed and developing countries, a review of the theoretical and conceptual framework of several performances appraisal models were conducted. The third phase of the review focused on performance appraisal in educational institutions in selected countries, as well as a review of Eric Alan Hanushek article on the role of human capital in economic growth in developing countries. Finally, the paper presented the findings and the research gaps identified in the review. In carrying out the first phase of this paper, the emphasis was placed on the importance of the context, which involves the interplay between the extrinsic (such as societal norms, economic and political situation of the country) and the inherent (institutional culture and leadership style) factors within which the HEI operates. Intrinsic and Extrinsic factors affecting the performance assessment of HEIs in Iraq, Kurdistan, have been reviewed. A similar review was carried out in HEIs in the United Kingdom and the United States of America to determine the extent to which organizational culture and social norms influence the formulation of performance appraisal models.

Keywords: Performance appraisal, higher education institution, institutional culture performance management.

INTRODUCTION

Redman et al. (2007), Prince et al. (2007), Ahmed (2016) and Ojeh et al. (2017) jointly revealed that both internal and external factors lead to the implementation of performance appraisal in an establishment. According to empirical evidence (Avery and McKay, 2004 Ojeh et al. 2017; Dauda and Luki, 2018), there is a split in opinion on performance appraisal among authors and experts. For example, Dulewicz (1989) sees performance appraisal as a planned and intermittent interaction between an employee and supervisors. This is carried out with the sole objective of determining and orchestrating relevant activities to enhance and boost the productivity of the employee indicated that performance appraisal is a process whereby supervisors examine the employees' output via a question and answer session. Lawrence (2014), on the other hand, sees performance appraisal as a means of assessing the productivity of workers in an organization, geared towards the identification of strong and weak points to boost efficiency. According to these experts, regardless of the model used, performance appraisal is critical for institutional performance.

However, on the contrary, Boachie-Mensah and Seidu (2011), Armstrong and Baron (2005), as well as Bohlander and Sneel (2004) strongly objected to the notion that all forms of models are instrumental to institutional higher performance. The authors indicated that unless the establishment orchestrates ground-breaking or context-driven administrative schemes, the organization would never stay ahead of its competitors. In effect, these experts thought that just any model cannot work. Administrative staff developing the model must incorporate components that impress on the minds of employees that will fast track their personal development and heighten professional qualification. Workers are likely to support the model. If employees suspect that the model places much emphasis on exposing their weaknesses with little contribution to their progress, this would likely recoil and resist the model. Hence, a group of experts (Anthony, Perrewe; Kacmar, 1999) asserted that if the model is transparent and workers can decipher its benefits, it will boost their confidence and support.

Given the controversy surrounding performance appraisal models, numerous models are formulated and orchestrated with varying degrees of success. This has resulted in the formulation of several models of performance appraisal in developed and developing countries to orchestrate the most effective approach to performance appraisal (Redman et al. 2007; Ahmed, 2016; Dauda and Luki, 2018). Owing to the aforementioned, smart administrative personnel around the world often review and critically examine various types of models around the world to formulate a practical, result-oriented and contextually driven performance appraisal in their organization. This forms the nexus of this paper.

The primary objective of this paper is to conduct a comparative analysis of several models of performance appraisal in developed and developing countries. The analysis is structured as follows: First, the contextual implications of performance appraisal models in developed and developing countries are examined; second, theoretical and conceptual underpinnings on performance appraisal were reviewed; the third phase of the review considered the performance appraisal in the selected countries, which was critically reviewed and analyzed in connection with what influences the model and its effectiveness in achieving the sole objective of performance appraisal; and fourth, which is the last segment of the paper, comprises the conclusion and gaps identified in the review.

METHODOLOGY

To conduct a thorough examination of the contextual implications of performance appraisal models in developed and developing countries, ten studies were chosen that used the hypothesis test to establish a link between several components of institutional culture and the extent of the relationship between the constructs, such as the involvement of both staff and supervisors in providing input during the performance assessment process, the level of system satisfaction, academic staff motivation, and support for top management. Furthermore, to better understand the various performance appraisal models for HEIs in both developed and developing countries, a notable model by Winston and Creamer (1998) was reviewed, on which a record number (64%) of studies on the appraisal system for this paper underpins their study.

A hypothesis was developed to critically examine the relationship between institutional culture and the various ways in which the performance appraisal system is used at the institution. Inferential statistics in the form of Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r) in Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) version 21 were used to determine the type of relationship that existed between the various components of institutional culture and effective performance appraisal systems from ten (10) articles. The paper reviewed some articles by Eric Alan Hanushek, an economist who has written extensively on public policy, with a focus on educational economics.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Contextual implications of performance appraisal models

A review of the literature reveals that the context which comprises the interplay of internal and external factors, within which an institution found itself alongside the prevailing societal norms and economic situation in a Country exerts much influence on its approach to performance appraisal models. For example, due to a variety of factors, the administrative staff of HEIs in Iraq, Kurdistan, an autonomous region of Iraq (developing country), was unable to develop an effective performance appraisal model. The High Education, Scientific Research Ministry (MoHESR, 2010) and Ahmed (2016) said that Iraq’s higher education system is "disorganized, and it has no accountability, democracy and transparency in its hierarchical management structure." Moreover, World Bank (2000), Blackmore et al. (2009) and Aslam (2011) asserted that Kurdistan lacks highly qualified and motivated HEI faculty members and well-established mechanisms to effectively evaluate staffs’ performance due to the decades of military and political upheavals and the resulting economic downturn and uncertain circumstances.

The formulated performance appraisal was later discovered to be ineffective because the model stipulates a mono approach to assessment. Rasheed et al. (2011) and Ala’Aldeen (2013) reported that with the existing model, Deans (managers in HEI) evaluate lecturers without their knowledge or participation. This report, according to Rasheed et al. (2011) and Ala’Aldeen (2013) is a secret endeavour performed annually via the completion of the Annual Confidential Report (ACR) form. Ala’Aldeen (2003) reported that students were not allowed to participate in assessing or appraising their lecturers. Moreover, the entire process lies with the Dean and whatever he or she reports is final.

However, MoHESR (2010) felt the model was ineffective and reviewed it by deploying new mechanisms to adequately evaluate and improve lecturers' efficiency in the faculties. Lecturers are required to attend workshops, seminars and conferences during a year. The newly formulated model also requires lecturers to give three presentations about the state of academic endeavour in their professional career. The model also stipulated that lecturers should prepare their lectures well in advance so that a proper assessment can be made regarding the objectives and goals for each course and the extent to which the lecturer develops a creative learning environment. To the surprise of many lecturers, the students were formally grafted into the performance appraisal model. Students are required to critically assess and evaluate the teaching staff and provide the administration with feedback which is considered by the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research (MOHESR) as critical to effective evaluation and assessment of a lecturers' performance. The students can readily provide the administration with firsthand information regarding teaching staff.

According to MOHESR-KRG (2010) and Ahmed (2016), the newly formulated appraisal model was rebuffed by several lecturers at UoS as an imposition of Western ideas on them. Mellahi (2006) indicated that in the Middle Eastern countries, performance appraisal is viewed from the perspective of improving the loyalty of a subordinate to his superior. This means any model measuring the performance of a lecturer through the quantity and quality of his or her research activities and teaching practice will be resisted. An extensive study by Appelbaum et al. (2011) on performance appraisal in the Middle East, Arab nations in general, findings revealed that there is little transparency when performance appraisal is conducted every activity is confidential. Lending credence to this conclusion, Weir (2000) asserted that in this region of the world, employees are often not informed or in the dark regarding why they are being punished or suspended at work.

In effect, both the internal and external factor influences make it difficult for MOHESR to formulate a model based on the principles of justice, fairness and ethics, which are highly instrumental to human resource development and enhancement of professional performance. It must be noted that the environmental factors influencing the performance appraisal model in Asian countries are vastly different from Arab countries. Shen (2004) indicated that because of the deeply etched culture of "saving face", which means helping others save embarrassing situations or providing constructive assistance to others so would be at ease. Japanese institutions value group meetings where both the employee and the supervisors are fully aware of the entire process of performance appraisal. Unlike the Arab countries, in Japan, workers are provided timely feedbacks on their strong and weak points to foster career development. Similarly, in India, Amba-Rao (1994) argued that performance assessment in several establishments is inherently characterized by ample and timely feedback of results to workers so that they can decipher areas that need improvement and concrete areas that are already doing well.

In developed countries such as the USA and the UK, performance appraisals were not initially used for measuring professional staff whether in the business or educational sector. It was originally used to assess military personnel to ensure that the required standard of operation. Wiese and Buckley (1998) indicated that it was later introduced to other sectors within the framework of blue-collar jobs. The authors posited that administrative staffs were not included in the system. The performance appraisal model in those early times in developed countries employed a scoring system for appraising individual workers. The model was designed to focus primarily on the past actions or performance of workers without any strategic influence on future activities, goals and career development. It must be noted that even in developed countries such as the USA and UK, there was little input from the workers, the system was not transparent initially, moreover the entire process is controlled by the supervisors and a top-down rigid framework.

However, in recent times, there is a major paradigm shift on the performance model with much emphasis on transparency and feedback in developed countries. Furnham and Chamorro?Premuzic (2004) indicated that most corporations now include administrative staff and professionals in performance appraisal models.

Takeuchi et al. (2007) as well as Smith and Collins (2006) argued that, instead of the interpersonal type of interaction between the character and traits of employees and administrative control, which may result in less understanding of the actual performance of individual employees, some corporations do not use in-person assessments that emphasize the professional development of employees, learning opportunities. What contributed to the implementation of models with administrative purpose was McGregor's (1957) theoretical underpinning tagged "Management by Objectives". In his assertion, McGregor places a great deal of emphasis on the assessment of workers on the rationale of short-term objectives, determined and implemented by both the supervisor and the staff, instead of a model solely controlled and coordinated by the supervisor, based on the personal characteristics and characteristics of individual workers.

A closer examination of the modern performance appraisal systems in several countries, both developed and developing countries, according to Murphy and Cleveland (1995) and Ahmed (2016), reveals that it is universally accepted as a critical component of managing human resources in organizations and educational institutions. Brudan (2009) posited that most of the models operative in several organizations now employ an interactive forum between individual, operational and organizational aspirations and goals alongside the introduction and growth of strategic performance appraisal models. According to Brudan (2009), this has led to the introduction of a Balanced Scorecard to integrate workers' career development with the results as dictated by the framework of assessment models. This is carried out with the sole aim of maintaining a competitive edge because both the strategic system of appraising staff and the structure of operations are compatible.

In brief, performance appraisal has become ubiquitous in the developed and developing world. Though, some experts such as Lucas and Katdare (2006), Redman et al. (2000) felt it is entrenched in the developed countries such as the UK and USA, empirical evidence and the review so far revealed that it is also operative in several other countries around the world.

Snape et al. (1998) indicated it is entrenched in Hong Kong, Brutus et al. (2006) posited that it is prevalent in Argentina and some countries in the Americas. Arthur et al. (1995) intimated that African countries such as South Africa are also enjoying the impact of the performance appraisal model in both public and private institutions. India, according to Lawler et al. (1995) and Lawler et al. (2012), is not left out in the benefit accruing from performance appraisal in Institutions.

At this juncture, it is essential to consider critically the nature of different forms of performance appraisal in developing and developed countries to analyze strengths and weaknesses in each of the models. The analysis brings to the fore, features that are inherent to the functional, practical and result-oriented performance appraisal model. However, before the analysis of the various forms of performance appraisal models, it is pertinent to discuss some theoretical underpinnings of performance appraisal and management to underscore its relevance within educational settings and contexts.

Control theory of performance management system

An analysis of the control theory was carried out because the performance appraisal model represents an essential and important aspect of human resources management, with the sole aim of harmonizing and improving the performance of employees and teams to the end of the improved institutional performance reflected in the career development of staff and academic prowess of students. The Performance Management System therefore measures, identifies and develops an institution's overall performance (Aguinis et al., 2011).

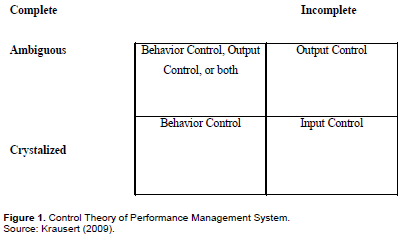

The theory of control was proposed to define different forms of control between both the institution as well as its systems. The control system, as per Barrows and Neely (2011), is designed to bring all processes within an entity in line with the overall goals, objectives and focus of an institution. Therefore, control mechanisms should then be laid down at all levels of an establishment from the viewpoint of control theory. The various aspects of controls designed to accelerate the achievement of the Institution's overall goals and objectives are stated as follows from the theory: structure of an institution; policies and standards capable of monitoring the equilibrium of behavior patterns within the organization; structures coordinated to assess institutional performance.

Dwivedi and Chetty (2016) asserted that the organization's controls must always connect with the organization's strategic objectives and goals. Neely and Barrow (2012) also posited that an institution's control system has three parts as outlined below.

1. Behavioral control: The organization or appraiser monitors and evaluates employees' activities per the stipulated standards of functioning within the establishment to achieve the spotlight of this method of control.

2. Output control: Under this scheme, the performance of employees depends on the standards of sanctions and rewards of the institution.

3. Input control: This method is used during the hiring process to pick and assess the training needs of the workers per Krausert (2009) who suggested that this program relies on the existence of necessary skills and competencies of the institution's workers meeting the standard required.

In other words, the worker's built-in skills and knowledge must be in line with the organization’s preferred level of competence before the recruitment and training programmes.

Control theory of performance management system

In the study, Shell (1992) made a remarkable assertion that organizational culture, standards, structure, administrative capacity and policies play a role in making such control mechanisms effective as depicted in Figure 1. Fundamentally, an Institution can achieve a competitive advantage by enhancing its performance through improved staff motivation (compensation), capacity (training), and workplace environment participation.

Performance appraisal in developed countries: UK

Despite the longstanding existence of the performance appraisal model in the United Kingdom, its relevance to heightening staves' development and organizational performance is still open to controversy. Literature reveals that there are several pockets of resistance to performance appraisal models in the UK. For example, Prahalad and Hamel (2010) and Dwomoh et al. (2014) asserted that over 80% of the corporations and establishments in the United Kingdom are in one way or another resisting performance appraisal with the argument that it does not necessarily motivate workers.

However, another study by Bowles and Coates (2009) discovered that over 68% of 48 corporations in the United Kingdom indicated their agreement and acceptance of the prevailing performance appraisal model in the UK. Providing additional insight into the matter, indicated that the institutional culture or approach to performance appraisal often dictates acceptance or rejection on most of the prevailing models in the UK. Notwithstanding, Jozwiak (2012) indicated that performance appraisal has become an intrinsically integrated aspect of Institutional management.

According to Jozwiak, over 80% of human resource professionals including the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development in the UK, agreed that performance appraisal and management is crucial to the public sector (including the educational sector) productivity and become the focal point of all HR management practices.

Adducing reason for such development, Horton (2006) outlined five major reasons as indicated below:

1. Several political regimes in the OECD desire to attain competency in the economy;

2. Public offices are expected to be occupied by highly professional state officials;

3. Initiation of a strong competition between non-Government institutions and Governmental agencies;

4. More transparency and openness is demanded by the citizenry;

5. The insistence of both Government and non- Governmental Institution on highly effective regimes and systems.

As a result, the new model of performance appraisal took sway in the United Kingdom with much emphasis on Institutional productivity and staff development. According to OECD (1995 and 1999) reports, every organization within the UK is expected to conform to the new performance appraisal with the following standard:

1. Shall be well-formulated to ensure proficiency;

2. Benchmarks for staff outputs should guide formal activities;

3. Employee evaluation models should determine staff and institutional outputs

At this point, performance appraisal was mandatory by all establishments and it should be carried out regularly. Employees are regularly assessed to fine-tune their productivity, improve personal development through incentives and additional training requirements. As indicated earlier, employees were unaware of the assessment process in the UK, but with the new model, both employees and supervisors are actively involved.

Due to this emphasis by OECD, Horton (2006) indicated that over 90% of private corporations regularly conduct employees’ performance appraisal while 100% of the public institutions are actively carrying out performance appraisal. In the new model for performance appraisal, the top-down approach to assessment is minimized because staffs are not privy to what is recommended regarding them and this paves way for the caprices and whim of supervisors.

However, Horton indicated that with the new approach, self-appraisal is encouraged and it opens a large door of opportunity for staff to take the bull by the horn and dictate the course of their assessment.

Further expanding the efficiency of performance appraisal in the UK, the Audit Commission was launched in the 1990s to critically examine the level of compliance by public institutions to the new model through publications. The commission standards were based on the following premise:

1. Descriptive and numerical approaches should determine the productivity level of Institutions;

2. All Institutions and establishment should regularly publish comments on the individual staff output and organizational output;

3. All Institutions should acknowledge the improvement in requisite skills of individual staffs with the sole aim of motivating them into increased performance;

4. In connection with HEIs in the UK, literature (Redman et al., 2000; Simmons, 2002) revealed that it is structured into two broad categories, namely, Stewardship-based models and Agency-based models.

In his study, Dauda and Luki (2018) posited that the Stewardship based model approach entails results that last for a long period and are influenced by organizational culture and awareness of the Society. Agency-based models, on the other hand, is primarily concerned with short-term results and influenced by regular assessment and appraisal. A critical appraisal of the two models revealed that the agency-based model is gaining an upper hand, although a blend of the two models is used in HEIs of the UK. This paper also discovered that due to the organizational culture of a certain corporation that dealt with long-term and complex objectives, administrative staffs are interested in the stewardship performance appraisal model.

By implication, it means those with short-term goals and objectives favour the agency-based model. Whereas institutions with both short-term and long-term goals, the objectives favour a hybrid model comprising both the stewardship and agency-based models. The review of the UK reveals that incumbent on the circumstance and context of each HEI, a model can be formulated to determine both individual and organizational outputs.

Performance appraisal in developing country: India

Chowdhury (2008), Kumar and Singla (2014) as well as Sing and Vadivelu (2016) reveal that India has a long history of actively assessing staff performance because the performance appraisal model is readily accepted by several corporations. Chowdhury (2008) indicated that some of the prevailing models in India place much emphasis on individual staff's work output, of which incentives are given to those who performed very well while those underperform are punished.

However, Chowdhury criticized some of the models as putting too much power into the supervisor's hand so that his interest is treated as paramount; staff interest is relegated to the background. Lending credence to Chowdhury submission, Jain and Ratnam (1994) and Sing and Vadivelu (2016), stated that the societal norm in India influences the model because "hierarchy and inequality" is an inherent feature of Indian society. Moreover, Kanungo and Mendonca (1994) indicated that most of the employees prefer a cordial relationship with their supervisors, thus, entrenching the hierarchy and inequality gaps.

Considering the above-mentioned flaws of modern performance appraisal, a recent establishment in India rejected it and launched a new model that places a strong emphasis on transparency, equality, and the personal attributes of employees. As a result, most of the establishments favor an appraisal system that emphasizes self-assessment which allows both the supervisor and the employee to actively participate in the assessment process. Sing and Vadivelu (2016) and Dauda and Luki (2018) intimated that at present most of the corporations in India follow the new model even though certain administrative staffs, especially those liking the contemporary performance appraisal are generating heated debate on the effectiveness of the new model.

Appraisal in developing country: Ghana

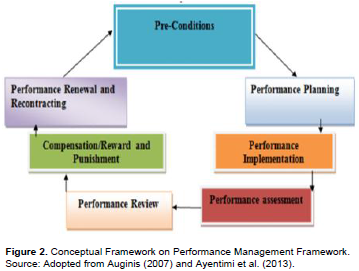

At present, performance appraisal in Ghana is highly transparent and entails the active involvement of the supervisor and the staff. Being the fulcrum of all educational activities, the Ghana Education Service (GES) coordinates all activities on performance appraisals. A closer look at pictorial illustrations in Figure 2 reveals that performance appraisal for education in Ghana follows Auginis (2007) and Ayentimi et al. (2013) model. As depicted in Figure 2, the first practice is Pre-Conditions.

The performance appraisal section deals with the two key prerequisites for efficient performance management, namely: ample knowledge of the appraisee task; adequate knowledge of the Institution’s goals and missions. This means that the evaluators who complete the form of GES's performance management system must have great knowledge of every aspect of the curriculum and other aspects of the profession.

The next phase is previously explained in Performance Planning because it covers the first phase of ME-SPRASO1. According to Aguinis (2007) and Newman and Milkovich (2008), both the instructors and the supervisor communicate to review the framework for what to do and how to do it. The supervisor will therefore critically examine the behaviors, development plan and performance useful to the performance management system integrated process.

The next phase is performance execution, described as a phase of action by both Newman (2008) and Aguinis (2009) solely to demonstrate competence and produce positive results together with good behavior, within the framework of the predefined set of requirements.

The fourth phase of the performance appraisal process is where the supervisor and the staff decide whether the desired outcome or objective is met. The activity of the employee is assessed. This segment of the procedure is critical since any outcome achieved for this segment serves as the basis for the following phase, as indicated by Pierce.

The performance review is where the formal assessment process is conducted because the activities of the employee concerning achievements, performance and development plans will be reviewed. The sixth phase includes compensation, sanctions or reward. It coincides with ME-SPRASO1's fourth section. Several authors, including Newman and Milkovich (2008) and Ayentimi et al. (2013), have asserted that, at this stage, "all forms of tangible services and benefits, as well as financial returns received by employees, are considered to be part of the employment relationship." Consequently, Stone (2005) indicated that penalties may be enforced if the performance outputs are negative and this will serve as motivation because the employee will decipher that penalties will be removed if his performance improves and the employee will be able to benefit from compensation and other benefits.

In Figure 2, the last part concerns re-contracting and renewal of performance according to Ayentimi et al. (2013), the final phases of management systems in performance. However, the only difference is that "the stage of re-contracting and renewal stage takes advantage of the insights and information derived from previous stages." This section reflects the performance plan segment. Though this is the last section of a review year, at the beginning of a new year, the process begins again. In seven time-tested practices, therefore, it is essential to keep the performance management system in line with the overall advancements in organizational performance.

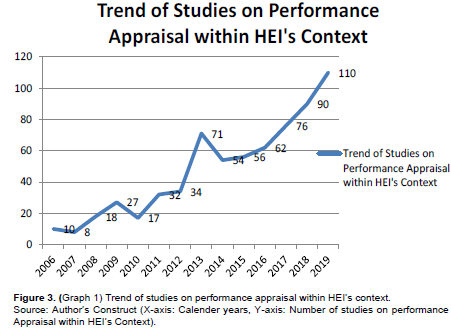

A systematic review of 50 studies drawn from developed and developing countries, as depicted in Graph 1, is very revealing as far as the relevance of performance appraisal is concerned within differing HEI's contexts worldwide. To achieve scientific rigour and to make a significant contribution to knowledge, existing studies are categorized based on a conceptual, theoretical and methodological framework. A comprehensive search for the related study was performed similarly to previous studies by Kim et al. (2012), Hence, peer-reviewed articles from reputable sources such as Emerald, EBSCO and ProQuest databases were used for the review.

A closer study of Figure 3 reveals a positive trend in connection with the implementation of performance appraisal in both developed and developing worlds. In 2007, fewer articles (8) discussed performance appraisal within HEI's. However, in 2013, it rose to 71 and interest in performance appraisal within the HEI context gained wide acceptance with articles rising to 100 in 2019. Findings of several studies (Kemper, 2005; Flaniken, 2009, indicated fierce competition within the HEI landscape led to increased demand for a higher standard of accountability from staffs and management of HEI's by the stakeholders including students, public officials and the general public.

However, in-depth analysis of the selected existing studies reveals that while some experts and HEIs management sees performance appraisal as evaluative (Alexander, 2000; Kemper, 2005, Becket and Brookes, 2006; Cardoso, et al., 2013), the others felt it should be directed more towards the professional development of staffs (Kambanda, 2008; Dechev, 2010) and yet others felt both approaches should be adopted to ensure holistic appraisal of staffs to the end of boosting staff motivation, enhance corporate communication and overall HEI effectiveness (Flaniken, 2009; Tuyishime, 2019).

Critique of Winston and Creamer (1998) model

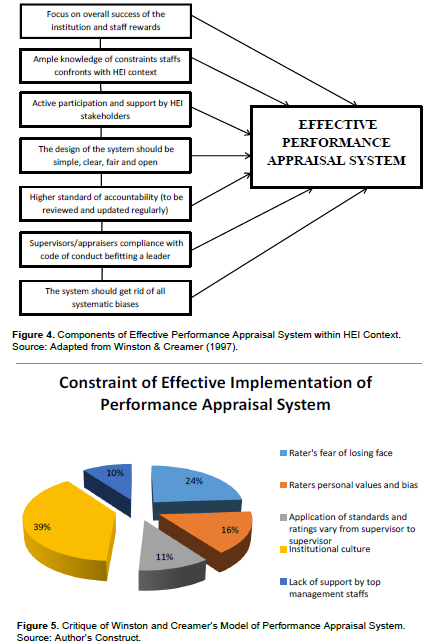

The majority of the studies (78%) revealed that there is increased awareness and adoption of the performance appraisal system within the HEI context. Several institutions are confronted with difficulties in effectively applying the process within their context of the operation. Through a notable model by Winston and Creamer (1998), upon which a record number (64%) of studies on the appraisal system underpins their study, offers a practical approach to a successful implementation of performance appraisal system, several gaps limit its applicability within HEI's.

As depicted in Figure 4, Winston and Creamer (1998) theorized that the inclusion of the underscored seven components will ensure effective employment of the performance appraisal system. However, the findings of several studies (79%), as depicted in Figure 5, show that these lofty components are constrained by the following issues as shown in this study.

From the proposed research perspective, Figure 5 demonstrated the difficulty of effectively implementing the principles of Winston and Creamers' model of performance appraisal system because, as shown above, even though the model specifies the required standard or qualities a rater or supervisor should possess, some of the selected studies show that factors such as institutional culture (39%), fear of losing face (24%), influence of personal values and biases (16%), a variation of rating standards from one supervisor to the other (11%) and lack of support by management staffs (21%) limits the efficacy of the model. Notable among these studies is Flaniken (2009) study that demonstrated that the Institutional culture exerts much pressure on the success of performance appraisal irrespective of the lofty components of Winston and Creamer (1998) model.

In effect, critical attention should be given to the culture of an institution to ensure the effective application of the performance appraisal system since it dictates the extent to which most of the seven components will be employed.

When Institutional culture is positive, it will compel raters or supervisors to conform to a lofty standard of performance appraisal, however, when it is negative, it erodes all other components in the model.

Hanushek's perspective on the role of human capital in economic growth in developing countries

Human capital is widely regarded as one of the most important components of effective organizational productivity and the use of an appropriate performance appraisal mechanism is regarded as a key catalyst for increasing employee productivity. In this regard, each organization should establish an effective appraisal framework in order to facilitate the continued development of its employees. This is particularly important for HEIs in countries where performance assessment systems are inherently flawed. Hanushek (2003) succinct perspective is being explored by looking at the context and role of a few critical human capital practices, primarily related to employee performance appraisal, and its impact on the economic growth of developing countries.

Hanushek's assessment of human capital and its impact on developing-country economic growth emphasized four main themes in his argument: the level of population cognitive skills is closely linked to the improvements to long-term growth; in contrast to educational or cognitive skills, development policy mistakenly emphasized educational attainment; while developing countries have improved their educational attainment, they have not improved their educational quality; in developing countries, school policy should focus on improving both basic and advanced skills. Employee selection procedures, performance appraisals, rewards and benefits, employee training and development, and other human capital practices, according to Hanushek, often have a direct impact on organizational productivity and performance.Human capital practices are the primary option for any company to influence and train employees' abilities, attitudes, and actions to complete its work and, as a result, achieve institutional goals (Collins and Clark, 2003; Martinsons, 1995).

The focus in developing countries on human capital as a driver of economic growth has resulted in an overabundance of attention paid to employee productivity measurement.

First, HEIs must ensure that the assessment process to be applied is objective, useful, practicable, accurate, and understandable so that workers in the sector can generally accept the appraisal feedback. Appraisals should also be performed by individuals who are well trained and qualified.

Furthermore, rather than focusing on punishment and redundancy, it should be focused on specific goals aimed at individual and collective improvement. Ultimately, the appraisal system should not be treated in isolation, but rather as part of a broader reform of the entire public sector management system.

Effects of institutional culture on effective performance appraisal

A hypothesis was formulated in a bid to critically examine the relationship between the institutional culture as reflected in several ways in which the institution applies the performance appraisal system, such as the mode of communication and the involvement of both supervisors and supervisors in the performance appraisal process, the level of satisfaction and commitment of staff, the support of senior management of the Institution.

Hypothesis:

H0: There is no significant relationship between institutional culture and an effective performance appraisal system within HEI's context.

H1: There is a significant relationship between institutional culture and an effective performance appraisal system within HEI's context.

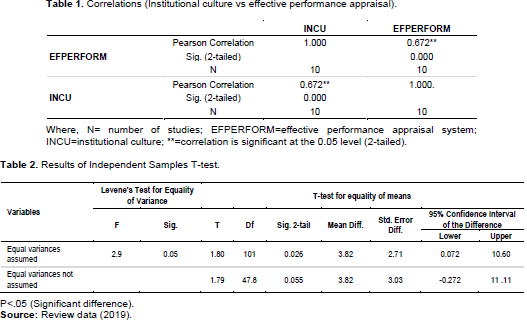

Inferential statistics in the form of Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r) in the Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) version 21 was initially used to ascertain the type of relationship existing between the various components of institutional culture and effective performance appraisal systems as shown in Table 1.

The Pearson Correlation Coefficient was run between ‘institutional culture and effective performance appraisal’. Results shown in Table 2 revealed a correlation coefficient (r) of 0.672 (p≤.005) which is strong and positive. It means Institutional culture is an important factor in effective performance appraisal. Being the most compelling attribute of an Institution, its culture is highly shown as instrumental in the successful implementation of an effective performance appraisal system. The finding of studies by Flaniken (2009), Adu (2016), Turk (2016) and Niyivuga et al. (2019) lend credence to the finding of this review since demonstrated that Institutional culture is the essence of an organization and representative of its approach to issues within and outside the Institution.

Hence it exerts much influence on the extent to which the performance appraisal system can be successfully implemented and maintained. Institutional culture, according to the above-mentioned studies, also dictates whether the organization will succeed in buoying the overall productivity of the Institution and retain a competitive edge amidst its competitors. To accept or reject the hypothesis requires ascertaining the level of significance since it is established that there is a relationship between the two variables.

At this juncture, it is pertinent to test the level of significance using the Independent Sample t-test utilizing Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) version 21 as depicted in Table 2. A closer study of Table 2, reveals that the mean of Institutional culture (M= 4.3451, SD=1.4324) and the mean of effective performance appraisal system (M=4.2625, SD= 1.5245) show that the difference is statistically significant (t=1.8, p=.026).

Therefore, because p<.05, the null hypothesis was rejected and it was concluded that there is a statistically significant effect of an Institutional culture of an effective performance appraisal system. The findings of this review are consistent with the result of studies by Flaniken (2009), Turk (2016), Adu (2016) and Niyivuga et al. (2019) which emphasizes the importance of nurturing a positive Institutional culture within the HEI context to facilitate a higher standard of accountability, professional development of staffs and improvement in the overall productivity of the Institution to effective performance appraisal system.

CONCLUSION

A critical examination of the review so far revealed that performance appraisal is continually changing due to the ever-changing world. Most of the contemporary models of performance appraisal as shown in the case of the UK approach to the assessment of staff. Empirical evidence shows that these countries have launched concerted efforts by recent administrative staff to encourage self- assessment which emphasizes transparency and active involvement of both the supervisor and the staff.

Much effort was expended in Ghana to ensure that individual employees are aware of any conclusions reached regarding their professional ability and qualification. This in turn fosters heightened Staff and Institutional performance. Ample evidence was garnered explicating the weakness of Winston and Creamer's (1998) theory of performance appraisal system arising from little or no recognition of several components of Institutional culture. Incisive inferential statistics underscoring the instrumentality of Institutional culture in facilitating the application of an effective performance appraisal system was also touched. Graph and figures were provided to buttress my contribution towards the urgent need of conducting extensive research into the formulation of a practical, up-to-date and result-oriented conceptual framework for a performance appraisal system within the HEI context.

Notwithstanding, a gap still exists on the extent to which staff are allowed to participate in their assessment. Most of the recent models of performance appraisal often lead to hostility and rancour because it goes contrary to societal norms which are deeply etched and entrenched in various communities around the world. Some experts indicated that cognition of the socio-economic conditions of a country and the market of an establishment is paramount to the attainment of the best result in the formulation of a performance appraisal model. At this juncture, it is paramount to resolve the contradictory evidence gap and the gap in knowledge regarding the relevance of balancing good practice in performance appraisal with socio-cultural norms within a society to reduce conflicts and rancour.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors have not declared any conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

|

Adu FK (2016). The use of performance appraisal in the University of Cape Coast: perception of senior administrative staff (Doctoral dissertation, University of Cape Coast. |

|

|

Aguinis H (2007). Performance Management. Edinburgh: Heriot-Watt. University. |

|

|

Aguinis H (2009). Performance Management (2nd ed). New Jersey: Upper Saddle River Pearson Education. |

|

|

Aguinis H, Joo H, Gottfredson RK (2011). Why we hate performance management-And why we should love it. Business Horizons 54(6):503-507. |

|

|

Ahmad R, Ali NA (2004). Performance appraisal decision in Malaysian public service. International Journal of Public Sector Management. |

|

|

Ahmed S (2016). Impact of Organizational Culture on Performance Management Practices in Pakistan. Business Intelligence Journal 5(1):50-55. |

|

|

Ala'Aldeen D (2013). Kurdistan: A Higher Education Evolution that Cannot Fail. [Internet]. |

|

|

Ala'Aldeen D (2003). A Vision to the future of Higher Education and Scientific Research in Kurdistan Region of Iraq.[Internet]. Available from: |

|

|

Alexander DM (2006). How do 360 degree performance reviews affect employee attitudes, effectiveness and performance?. |

|

|

Amba-Rao S (1994). US HRM Principles: Cross-country Comparisons and Two Case Applications in India. International Journal of Human Resource Management 5(3):755-779. |

|

|

Appelbaum S, Roy M, Gilliland T (2011). Globalization of performance appraisals: theory and applications. Management Decision 49(4):570-585. |

|

|

Armstrong M, Baron A (2005). Managing performance: performance management in action. CIPD publishing. |

|

|

Arthur Jr W, Strong MH, Jordan JA, Williamson JE, Shebilske WL, Regian JW (1995). Visual attention: Individual differences in training and predicting complex task performance. Acta Psychologica 88(1):3-23. |

|

|

Aslam H (2011). Performance Evaluation of Teachers in Universities: Contemporary Issues and Challenges. Journal of Educational and Social Research 1(2):11-30. |

|

|

Arthur W, Woehr D, Akande A, Strong M (1995). Human resource in West Africa: practices and perceptions. International Journal of Human Resource Management 6(2):61-347. |

|

|

Avery DR, McKay PF (2010). 6 Doing Diversity Right: An Empirically Based Approach to Effective Diversity Management. International review of industrial and organizational psychology 25:227. |

|

|

Ayentimi DT, Pongo N, Obinnim E, Osei-Yaw F, Naa-Idar F (2013). An Investigation into Performance Management Practices in Ghana: Case Study of Oti-Yeboah Company Limited. International Journal of Business and Management Tomorrow 3(9). |

|

|

Barrows E, Neely A (2011). Managing performance in turbulent times: analytics and insight. John Wiley & Sons. |

|

|

Blackmore K, Jones HM, Jerew OD (2009). On the minimum number of neighbours for good routing performance in MANETs. In 2009 IEEE 6th International Conference on Mobile Adhoc and Sensor Systems pp. 573-582. |

|

|

Boachie-Mensah FO, Seidu PA (2012). Employees' perception of performance appraisal system: A case study. International journal of business and management 7(2):73. |

|

|

Bohlander GW, Snell S, Morris S (2015). Managing human resources. Cengage Learning. |

|

|

Bowles ML, Coastes G (1993). Image and Substance: The Management of Performance as Rhetoric or Reality? Personnel Review 22(2):3-21 |

|

|

Brudan A (2009). Integrated performance management: Linking strategic, operational and individual performance. In PMA Conference. Dunedin: University of Otago-NZ. |

|

|

Brutus S (2006). Words versus numbers: A theoretical exploration of giving and receiving narrative comments in performance appraisal. Human Resource Management Review 20(2):144-157. |

|

|

Chowdhury SN (2008). Developing performance appraisal system for performance leadership in banks. |

|

|

Collins CJ, Clark KD (2003). Strategic human resource practices, top management team social networks, and firm performance: The role of human resource practices in creating organizational competitive advantage. Academy of management Journal 46(6)740-751. |

|

|

Dauda Y, Luki BN (2021). Perspectives on Performance Appraisal Practices in Organizations. GSJ 9(5). |

|

|

Dulewicz V (1989). "Performance Appraisal and Counselling, In: Herriot, P., (ed.), Assessment and Selection in Organisations: Methods and Practices for Recruitment and appraisal", John Wiley and Sons, New York pp. 645-649. |

|

|

Dwivedi A, Chetty P (2016). Control theory of performance management system. Retrieved August, 25, 2020. |

|

|

Flaniken FW (2009). Performance appraisal systems in higher education: An exploration of Christian institutions. University of Central Florida. |

|

|

Furnham A, Chamorro?Premuzic T (2004). A possible model for understanding the personality?intelligence interface. British Journal of Psychology 95(2):249-264. |

|

|

Hanushek EA (2013). Economic growth in developing countries: The role of human capital. Economics of education review 37:204-212. |

|

|

Horton S (2006). General Trends and challenges regarding performance evaluation of staff: The UK experience. In Portsmouth University United Kingdom Seminar on "Civil Service Performance Appraisal" Vilnius pp. 23-24. |

|

|

Jain HC, Ratnam CV (1994). Affirmative action in employment for the scheduled castes and the scheduled tribes in India. International Journal of Manpower. |

|

|

Jozwiak G (2012). "Is it time to give up on performance appraisals?", in HR Magazine, St. Jude's Church, Dulwich Road, London. |

|

|

Kanungo RN, Mendonca M (1994). Managing human resources: The issue of cultural fit. Journal of Management Inquiry 3(2):189-205. |

|

|

Kim SY, Peel JL, Hannigan MP, Dutton SJ, Sheppard L, Clark ML, Vedal S (2012). The temporal lag structure of short-term associations of fine particulate matter chemical constituents and cardiovascular and respiratory hospitalizations. Environmental health perspectives 120(8)1094-1099. |

|

|

Krausert A (2009). Performance Management for Different Employee Groups: A Contribution to the Employment Systems Theory. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. |

|

|

Kumar R, Singla N (2014). Cryptanalytic performance appraisal of improved CCH2 proxy multisignature scheme. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2014. |

|

|

Lucas NC, Katdare DA (2006). Chemosignals of fear enhance cognitive performance in humans. Chemical senses 31(5):415-423. |

|

|

McGregor D (1957). "An uneasy look at performance appraisals", Harvard Business Review 35(3):89?95. |

|

|

Mellahi K (2006). Human resource management in Saudi Arabia. In Managing Human Resources in the Middle-East. pp. 115-138. Routledge. |

|

|

Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research (MOHESR). (2010). Undergraduate Student Enrollments in Public Universities, 2004-2005. Khar-toum: MOHESR. |

|

|

Niyivuga B, Otara A, Tuyishime D (2019). Monitoring and evaluation practices and academic staff motivation: Implications in higher education within Rwandan context. SAGE Open 9(1):2158244019829564. |

|

|

Ojeh N, Sobers-Grannum N, Gaur U, Udupa A, Majumder MAA (2017). Learning style preferences: A study of Pre-clinical Medical Students in Barbados. Journal of advances in medical education & professionalism 5(4):185. |

|

|

Prince ED, Snodgrass D, Orbesen ES, Hoolihan JP, Serafy JE, Schratwieser JE (2007). Circle hooks,'J'hooks and drop?back time: a hook performance study of the south Florida recreational live?bait fishery for sailfish, Istiophorus platypterus. Fisheries Management and Ecology 14(2):173-182. |

|

|

Redman T, Snape E, Thompson D, Ka?Ching YF (2000). "Performance appraisal in a NHS hospital", Human Resource Management Journal 10(1):48?62. |

|

|

Redman-White W, Dong Y, Kraft M (2007). Higher order noise-shaping filters for high-performance micromachined accelerometers. IEEE transactions on instrumentation and measurement 56(5):1666-1674. |

|

|

Shen J (2004). International performance appraisals: policies, practices and determinants in the case of Chinese multinational companies. International Journal of Manpower. |

|

|

Simmons J (2002). An "expert witness" perspective on performance appraisal in universities and colleges. Employee relations. |

|

|

Sing R, Vadivelu S (2016). Performance Appraisal in India-A Review. International Journal of Applied Engineering Research 11(5):3229-3234. |

|

|

Smith KG, Collins CJ (2006). Knowledge exchange and combination: The role of human resource practices in the performance of high-technology firms. Academy of Management Journal 49(3):544-560. |

|

|

Snape ED, Thompson D, Yan FKC, Redman T (1998). Performance appraisal and culture: practice and attitudes in Hong Kong and Great Britain. International Journal of Human Resource Management 9(5):841-861. |

|

|

Takeuchi R, Lepak DP, Wang H, Takeuchi K (2007). An empirical examination of the mechanisms mediating between high-performance work systems and the performance of Japanese organizations. Journal of Applied psychology 92(4):1069. |

|

|

Turk K (2016). Performance management of academic staff and its effectiveness to teaching and research-Based on the example of Estonian universities. Trames 20(1):17-36. |

|

|

Wiese DS, Buckley MR (1998). The evolution of the performance appraisal process. Journal of management History. |

|

|

Winston Jr. RB, Creamer DG (1998). Staff supervision and professional development: An integrated approach. New Directions for Student Services 1998(84):29-42. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0