ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to examine how people within individualistic and collectivistic cultures differ in their intentions to seek professional mental health help. As such, it was crucial to examine possible predictors of intention to seek help for mental health issues. We explored the cultural differences between American and Japanese students and their intentions to seek help from mental health professionals. A total of 155 undergraduate students from America and 116 undergraduate students from Japan participated in this quantitative study. Participants completed surveys regarding public stigma, self-stigma, self-efficacy, confidence in mental health professionals, and intention to seek help. A 2 × 2 MANOVA was performed to test the hypotheses. The American college students had less public and self-stigma and had more self-efficacy, confidence in mental health professionals, and intention to seek help compared to the Japanese college students. Interventions for eradicating public and self-stigma and increasing self-efficacy are further discussed.

Key words: Mental health, public stigma, self-stigma, self-efficacy, confidence in mental health professionals, intention to seek help, college students, cross-cultural research.

The intention to seek professional mental health help and the stigma surrounding help seeking can vary across cultures depending on specific cultural norms (Mojaverian et al., 2013; Vogel et al., 2017). For instance, individuals in the Eastern world tend to be more interdependent and have encompassing social relationships with each other, with thoughts, feelings, and actions that are contingent on these relationships (Markus and Kitayama, 1991). As such, the act of seeking help outside of these encompassing social relationships may lead to the interruption of interpersonal relationships for individuals within collectivistic societies (Mojaverian et al., 2013), such as Japan, and collectivism has been found to be negatively associated with having positive, help-seeking attitudes (Sun et al., 2016). Furthermore, people in collectivistic cultures prioritize emotional restraint over emotional expression e.g., discussing mental health issues (Chen et al., 2015).

In comparison, individuals in the western world, such as Americans, tend to be more independent and are encouraged to be autonomous and self-enhancing and place importance on personal identity (Wang and Lau,

2015; Yıldız and ÅžimÅŸek, 2016). Moreover, there is less emphasis on considering the ingroup and those close to individualists when making decisions, such as seeking help, and the decision to seek help from mental health professionals may not be influenced by individuals’ relationships with others. Indeed, previous researchers have found that Asians and Asian Americans tend to underutilize mental health services (Kikuzawa et al., 2019; Kim and Zane, 2016), while the prevalence of certain mental illnesses is relatively similar between America and Japan (Inaba et al., 2005). Researchers have also found that Asians tend to avoid seeking mental health services and frequently terminate therapy prematurely in comparison to Americans, and they may also delay seeking help in general (Atkinson and Gim, 1989; Han and Pong, 2015). Due to these findings, it is necessary to examine the differences between American and Japanese individuals’ intentions to seek professional mental health help.

The purpose of this exploratory study was to examine the cultural differences of public stigma, self-stigma, self-efficacy, and confidence in mental health professionals’ abilities between American and Japanese college students. We then considered how these differences influence students’ help-seeking intentions. Such investigation is vital since it helps identify effective ways to reach out to many Asian and Asian American individuals who are suffering through mental health struggles without sufficient treatment.

REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE

Effects of stigma on intention to seek help

Previous researchers have focused on the effects of stigma on attitudes toward seeking, and intention to seek, mental health services (Clement et al., 2015; Corrigan, 2004). In fact, these researchers revealed that stigma was a significant predictor of barriers to seek help. In particular, researchers have revealed that Americans are less concerned about the stigma that comes from others (that is, public stigma) than Japanese individuals are (Mojaverian et al., 2013), and this finding holds true for those seeking help for mental health concerns. Japanese individuals are readily concerned about the results that their actions may bring toward other members of their ingroups e.g., focusing on ingroup harmony (Hui and Triandis, 1986; Su et al., 2015), as actions that go against one’s ingroup could be seen as disruptive (Mojaverian et al., 2013). Furthermore, it is considered less appropriate to disclose personal issues in Japan. In a study of personal control and social accommodation, researchers found that choosing to disclose to others is regarded as more appropriate in western (individualistic) cultures compared to eastern (collectivistic) cultures (Ishii et al., 2017).

Corrigan (2004) identified two types of stigma associated with mental health and psychological services: public stigma and self-stigma. Public stigma is the act of discriminating against individuals with mental illness (Corrigan, 2004; Saavedra et al., 2020), and this term is used to describe how the public treats individuals who seek professional mental health help. Mental illnesses and seeking help for them are both widely stigmatized in Japan (Kasahara-Kiritani et al., 2018; Shimotsu et al., 2014). As a result, Japanese students view the disclosure of mental illnesses less favorably than U.S. students do (Masuda et al., 2005). This is possibly due to the negative consequences that could occur from being stigmatized and from being afraid of bringing disharmony to their families or inner circles. In a recent study of Japanese college students, researchers found that reducing public stigma toward mental illnesses in young people could enable them to utilize mental health resources (Koike et al., 2018). Yamawaki et al. (2011) found that more Japanese individuals see mental illness as a weakness compared to those living in individualistic countries. Furthermore, Japanese people accept the belief that having a weak personality causes mental illnesses, a belief that contributes to public stigma in Japan (Yoshioka et al., 2016). Therefore, the first hypothesis is: Public stigma would show greater significant impact on intention to seek help among Japanese participants than among American participants.

Public stigma influences the development of self-stigma, a facet in determining if individuals seek help (Vogel et al., 2007), in individuals with mental illnesses, leading to decreased intention to seek help and limiting the establishment of positive attitudes about oneself (Vogel et al., 2013). Self-stigma is the act of personally internalizing the public stigma being displayed by other people and the stereotypes surrounding mental illness (Corrigan, 2004; Corrigan et al., 2016; Heath et al., 2018; Vogel et al., 2013). Researchers have found that self-stigma results in treatment avoidance and decreased participation in treatment (Corrigan, 2004; Vogel et al., 2013).

In a study with a 90% European American sample (which represents a highly individualistic culture), self-stigma was found to be a more prominent predictor of help-seeking attitudes than public stigma, and self-stigma was negatively related to peoples’ attitudes about and intention to seek help from mental health professionals (Vogel et al., 2007). This could partially be due to the fact that people in individualistic cultures are encouraged to promote and maintain their distinctiveness from others (Taylor et al., 2004). Therefore, self-stigma would be an important determining factor to individualistic people regarding seeking help because self-stigma pertains to the self and upholds one’s distinctiveness from others. However, since self-stigma is heavily influenced by public stigma e.g., higher public stigma can result in higher self-stigma (Vogel et al., 2006, 2017), it may be a significant predictor of intention to seek help in both collectivistic and individualistic cultures. Therefore, the second hypothesis is: There would be a significant main effect of self-stigma, while there would not be any significant difference between Japanese and American participants on one’s intention to seek help.

Effects of self-efficacy on intention to seek help

Self-efficacy might be also a significant predictor between collectivistic and individualistic cultures of one’s intention to seek help (O’Connor et al., 2014). Self-efficacy is an individual’s belief about the competence they have to complete an action for a specific goal (Bandura, 1986), and it is the perception of one’s ability to engage in certain behaviors and be successful in doing so (Florer, 2015). Previous researchers have found that adherence to European American values is positively related to self-efficacy (Kim and Omizo, 2005) and is beneficial for one’s mental health (Alamilla et al., 2017). Americans have been found to place greater importance on self-efficacy than individuals in collectivistic cultures (Chen et al., 2006; Yıldız and ÅžimÅŸek, 2016), with general self-efficacy being less important for Japanese individuals (Kiuchi, 2006). While researching three groups of students (European American students, Japanese international students in America, and native Japanese students in Japan), Kiuchi (2006) found that, while all three groups placed priority on independent construals of the self, native Japanese students in Japan ranked independent construals of the self as the lowest in priority and were the least independent of the three groups. This finding suggests that one’s self-efficacy may be related to one’s independent construal of the self, and other researchers have found that one’s independent construal of the self is positively related to self-efficacy (Suryaningrum, 2018). Because collectivistic individuals focus on maintaining both group harmony and their relationships with their ingroups, they may be less interested in constructing an independent construal of the self because their identities rely heavily on their ingroups instead of themselves.

Other researchers have found that Japanese individuals have lower scores of self-efficacy than do Americans and people from other individualistic cultures (e.g., Lithuania), and this research supports the finding that collectivistic cultures yield lower levels of self-efficacy as a whole (Kononovas and Dallas, 2009). Indeed, a previous study showed this finding by using general self-efficacy to measure respondents’ overall self-efficacy to predict help-seeking attitudes and behaviors (Corrigan et al., 2006). However, according to Eden and Granat-Flomin (2000), self-efficacy in a specific domain could much more efficiently predict specific domain behavior while general self-efficacy could not. For the purpose of this study, we perceive that it is vital to examine the effect of respondents’ self-efficacy to overcome psychological problems with the help of mental health professionals on their intention to seek help. Therefore, the third hypothesis is: Self-efficacy to overcome psychological problems would show greater significant impact on one’s intention to seek help among American participants compared to Japanese participants.

Confidence in mental health professionals’ abilities

When seeking help to overcome mental illness, having confidence in the abilities of mental health professionals is crucial. Researchers have found that the responsiveness of professionals, which was coded as professionals’ competence (e.g., ability), was found to be strongly related to peoples’ confidence in mental health professionals (Zartaloudi and Madianos, 2010). Zartaloudi and Madianos (2010) also found that people who had friends who previously sought help from a mental health professional were less concerned about mental health professionals’ abilities to help them with their own mental illnesses. In their multidimensional model, Fischer and Turner (1970) stated that positive help-seeking attitudes involve the confidence that individuals have in mental health professionals’ abilities to help with mental illnesses. Other researchers using this model have found that being a woman and having previously received mental health help are both connected to having positive help-seeking attitudes, including more confidence in mental health professionals’ abilities (Masuda et al., 2005). In fact, researchers found that American students reported having more favorable attitudes toward mental health professionals’ abilities than did both Japanese and Asian-American students (Masuda and Boone, 2011; Masuda et al., 2005).

Other researchers have found that having an ethnic identity that corresponds to a collectivistic culture is negatively correlated with attitudes of seeking help (Li et al., 2016). Japanese students who previously sought help had more confidence in the abilities of mental health professionals than Japanese students who had never sought help (Masuda et al., 2005). However, even though past experiences with mental health professionals increased Japanese students’ confidence in seeking help, American students were still found to be more confident in mental health professionals’ abilities than were these Japanese students (Masuda et al., 2005).

Description of the sample/procedure

American participants were recruited from an undergraduate student research pool in the psychology department at a large private university in the Rocky Mountain region in America, and they received research credit that fulfilled course requirements. A total of 155 American students (65 men and 90 women) participated in this quantitative study, and their ages ranged from 18 to 36 (M = 20.75, SD = 2.96). Among American participants, 87% identified themselves as Caucasian American, 6% Hispanic American, 6% Asian American, and 1% as other. Approximately 80% were single, 18% were married, and 2% were divorced. As for Japanese participants, we invited university instructors who are members of the Japan Mental Health Research Association to assist in collecting responses from Japanese students. Two instructors from one Japanese private university agreed to collect data in their classes on a completely volunteer basis. They all were undergraduate students taking introductory college classes at a large private university in the metropolitan area of Japan. A total of 116 Japanese students (43 men and 73 women) participated in this study, and their ages ranged from 18 to 23 (M = 18.53, SD = 0.88). All students were unmarried. All participants consented to participate in this study and received research credit that fulfilled a course requirement.

Translation

All measures and the consent form used in the present study were translated from English into Japanese by a professional Japanese translator. The Japanese versions of these materials were then translated from Japanese into English by a Japanese university instructor fluent in both languages. This individual was not shown the original English version. All materials were evaluated by a bilingual psychologist to make sure that the translations were accurate and that the content was the same.

Instruments and measurements

Intention to seek counseling for psychological and interpersonal concern (ISCPIC) (Cash et al., 1975). The ISCPIC was measured by the Intent to Seek Counseling Inventory (ISCI), which is a widely used and validated scale that is designed to measure the degree to which respondents are willing to seek help from mental health professionals. The ISCI consists of three subscales: 10 items for “Psychological and Interpersonal Concern,” four items for “Academic Concern,” and two items for “Drug Use Concern.” For the purpose of this cross-cultural study, only the Psychological and Interpersonal Concern subscale was used. The subscale asks respondents about their intention to seek help when they have depression, anxiety, loneliness, or feelings of inferiority. Respondents were asked to rate items on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (“Not likely”) to 5 (“Very likely”). All 10 items were summed, and higher scores represent greater intention to seek mental health treatment. The Cronbach’s alphas of this subscale for Japanese and American data were 0.94 and 0.87, respectively.

Stigma of seeking professional psychological help (SSPPH) (Komiya et al., 2000). The SSPPH contains five items that are designed to assess respondents’ perceptions of the societal stigma associated with seeking professional psychological help. Respondents were asked to rate all five items on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 5 (“Strongly agree”). One example item is “People tend to react negatively to those who are receiving professional psychological help.” Participants’ scores were totaled, and higher scores denote respondents’ perception of greater societal stigma toward seeking professional help. The Cronbach’s alphas of this measure were 0.87 for Japanese participants and 0.89 for American participants.

Self-stigma of seeking help (SSOSH; Vogel et al., 2006). This measure was designed to evaluate the degree to which participants self-evaluated for seeking psychological help. It consists of 10 items, such as “My self-confidence would NOT be threatened if I sought professional help.” All 10 items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 5 (“Strongly agree”). One item (the one used as a sample earlier) was reverse scored and summed with all other items. Therefore, higher scores indicate greater self-stigma for seeking help. The Cronbach’s alphas of this measure were 0.31 for Japanese respondents and 0.39 for American respondents. Due to these low reliabilities and to ensure that both Japanese and American data show similar patterns of self-stigma, principal component factor analyses were performed separately for Japanese and American data. In particular, a one-factor solution with varimax rotations was imposed since this measure is designed to assess one component of self-stigma. Items were dropped that did not load highly (greater than 0.50) on one factor, and this analysis resulted in similar patterns in loading for both countries. Four items were dropped, and a total of six items were selected for the final self-stigma scale for this data. Those six items were (a) “I would feel inadequate if I went to a therapist for psychological help,” (b) “My self-confidence would NOT be threatened if I sought professional help,” (c) “Seeking psychological help would make me feel less intelligent,” (d) “It would make me feel inferior to ask a therapist for help,” (e) “If I went to a therapist, I would be less satisfied with myself,” and (f) “I would feel worse about myself if I could not solve my own problems.” One item, (b) was reverse scored and summed to the other five items. Higher scores indicate the strength of respondents’ self-stigma toward seeking professional help. The Cronbach’s alphas for the final, six-item measure were 0.89 for Japanese participants and 0.82 for American participants.

Self-efficacy to overcome psychological problems with help of mental health professionals (SEOPPHMHP). In a previous study, some researchers used the General Self-Efficacy Scale to measure respondents’ overall self-efficacy (Corrigan et al., 2006) to predict help-seeking attitudes and behaviors. However, according to Eden and Granat-Flomin (2000), self-efficacy in a specific domain could much more efficiently predict specific domain behavior, while general self-efficacy could not. Therefore, the SEOPPHMHP was developed for the purpose of this study. The SEOPPHMHP refers to respondents’ judgments of their capability to overcome psychological problems successfully with professional help. The SEOPPHMHP contains 10 items and was constructed following the suggestions offered by Bandura (2006) and Lent and Brown (2006). Items for this measure were generated from existing published self-efficacy scales, that is, Career Decision Making Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form (Betz et al., 1996) and Career Search Efficacy Scale (Solberg et al., 1994). Respondents were asked to rate their degree of confidence in their ability to overcome psychological problems with help from mental health professionals on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 5 (“Strongly agree”). All items were summed, and higher scores represent greater self-efficacy to overcome psychological problems with the help of mental health professionals. The Cronbach’s alphas for this measure for Japanese and American participants were 0.89 and 0.81, respectively.

Confidence in mental health professionals (CMHP). The CMHP was created to measure respondents’ confidence in mental health professionals in general. It contains five items, and respondents were asked to rate their general confidence in mental health professionals on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 5 (“Strongly agree”). Typical items for the CMHP are “In general, I am (a) ‘confident that mental health professionals are competent,’ (b) ‘confident that mental health professionals are effective,’ (c) ‘worried that mental health professionals do not have the ability to assist individuals to overcome their problems,’ (d) ‘confident that mental health professionals have the knowledge and skills to help people effectively’, and (e) ‘worried that mental health professionals cannot understand peoples’ problems.’” Items (c) and (e) were reverse scored and then all items were added to create the CMHP. Therefore, higher scores represent greater confidence in mental health professionals. The Cronbach’s alphas for this scale for Japanese and American respondents were 0.77 and 0.83, respectively.

Country and gender differences in public and self-stigma, intention to seek help, and self-efficacy

First, we performed a 2 (country) × 2 (gender) MANOVA with country and gender as independent variables and with public stigma, self-stigma, intention to seek help, and self-efficacy as dependent variables. Then, multivariate analyses of covariance (MANCOVA) were conducted to control for respondents’ general confidence in mental health professionals.

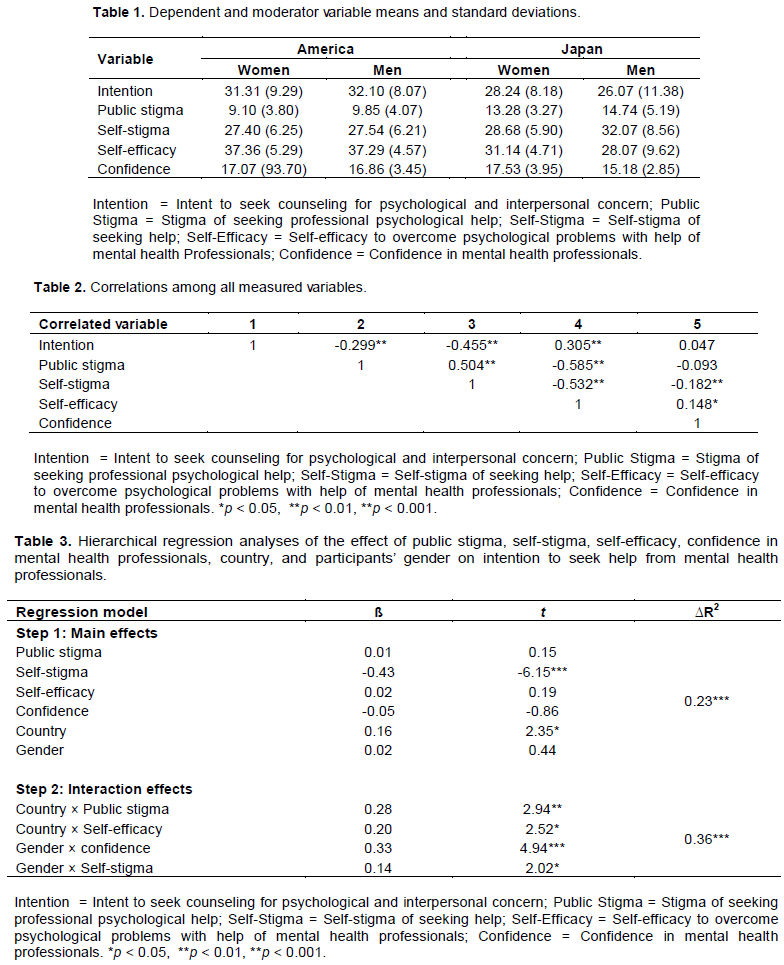

Means and standard deviations on the measured variables as functions of country and gender are shown in Table 1. Neither marital status nor age predicted intention to seek help in this study either directly or in an interaction with other variables. In line with the hypothesis, there was a significant main effect for country (F [4, 263] = 38.02, p < 0.001, r = 0.37). This analysis found no main effect for gender and no interaction effects (F [4, 263] = 1.83, p = n.s.; F [4, 263] = 1.21, p = n.s., respectively). A follow-up univariate test revealed that Japanese participants tended to hold greater public stigma and self-stigma than did American participants (F [1, 269] = 81.37, p < 0.001, r = 0.24; F [1, 269] = 12.28, p < 0.001, r = 0.05), respectively. Conversely, Japanese participants tended to hold less intention to seek professional help and less self-efficacy to overcome psychological problems with the help of mental health professionals compared to American participants (F [1, 269] = 15.86, p < 0.001, r = 0.06; F [1, 269] = 82.93, p < 0.001, r = 0.24), respectively.

Results of a MANCOVA indicated that there were main effects of both country and gender of participants (F [4, 262] = 37.29, p < 0.001, r = 0.36; F [4, 262] = 2.41, p < 0.05, r = 0.04), respectively. An ANCOVA indicated that even when controlling for confidence in mental health professional, Japanese participants were still likely to hold greater public and self-stigma and had less intention to seek help and self-efficacy in comparison to American participants (F [1, 262] = 79.29, p < 0.001, r = .23; F [1, 262] = 10.71, p < 0.001, r = 0.04; F [1, 262] = 15.32, p < 0.001, r = 0.06; F [1, 262] = 104.22, p < 0.001, r = 0.28), respectively. As such, the difference in confidence in mental health professionals between Japanese and American participants did not have a significant impact on the difference on the dependent variables between the countries.

One of the main differences between the MANOVA and MANCOVA results was that gender differences became significant after controlling for confidence in mental health professionals. ANCOVA results revealed that public and self-stigma as well as self-efficacy were all significant (F [1, 262] = 5.39, p < 0.05, r = 0.02; F [1, 262] = 7.00, p < 0.001, r = 0.03; F [1, 262] = 5.87, p < 0.05, r = 0.02), respectively. That is, male participants, in general, tended to hold greater public and self-stigma and self-efficacy with the help of mental health professionals than did female participants.

Effects of public and self-stigma and self-efficacy on intention to seek professional help

All measurements were centered to the means in order to reduce the possibility of multicollinearity influencing the results prior to the analyses (Jaccard et al., 1990). Participants’ gender was not part of our hypotheses, but it is included in all of the analyses. Zero-order correlation coefficients for all variables are shown in Table 2. Overall, statistically significant correlations emerged among all the measured variables at p < 0.05 except for the relationship between intention to seek help and public stigma and the relationship between intention to seek help and confidence in mental health professionals (n.s.). The correlations among the measured variables that were significant ranged from r = 0.182 to r = 0.585. To investigate any potential moderators on intention to seek professional help, hierarchical regression analyses were performed. In the first model, country, public stigma, self-stigma, self-efficacy, confidence in mental health professionals, and gender of the participants on intention to seek help were entered. Then, two-way interaction terms were entered in the second model. The results of these analyses are summarized in Table 3.

The results of the first model indicated a main effect of country and self-stigma. That is, Americans tended to show greater intention to seek professional help than did Japanese individuals, and participants who endorsed greater self-stigma toward seeking mental health help were less likely to seek help (Table 3). These main effects grant the further analysis of an interaction effect. As such, all two-way interaction terms were entered for intention to seek professional help in the second model. When the interaction terms were entered, country, self-stigma, country × public stigma, country × self-efficacy, gender × confidence, and gender × self-stigma became significant predictors of intention to seek help. To investigate the pattern of the interaction, simple effect analyses were conducted. The results revealed that self-efficacy was a significant predictor in Japan (β = -0.25, p < 0.05) but was not a significant predictor in America (β = 0.04, p = n.s.). The effect of public stigma in America was small (β = -0.18, p < 0.05), while it was significant in Japan (β = -0.43, p < 0.001). As for the gender x confidence interaction, a simple effect analysis revealed that confidence in mental health professionals positively predicted intention to seek help among women (β = 0.40, p < 0.001), while it was a negative predictor among men (β = -0.25, p < 0.001). Furthermore, self-stigma was a significant predictor among men (β = -0.49, p < 0.001) but was not a significant predictor among women (β = -0.11, n.s).

The purpose of this study was to examine the differences between American and Japanese students regarding intentions to seek help for mental illnesses. We examined the following possible variables that could influence intentions to seek help: public stigma, self-stigma, self-efficacy, and confidence in mental health professionals’ abilities.

As hypothesized, public stigma had a greater impact on intentions to seek help for Japanese individuals than for Americans. With this finding, we recommend taking actions to reduce public mental health stigma in Japan. In one systematic review, researchers found that mass media campaigns and interventions for target groups concerning stigma-related knowledge, intended behaviors, and attitudes about mental illnesses helped reduce public stigma toward mental health problems (Gronholm et al., 2017). Other researchers have recommended the following interventions for reducing public stigma: employing mass anti-stigma interventions, improving knowledge about mental health, making available more literature about mental health, implementing educational programs for students, facilitating direct and positive contact with individuals who have mental illnesses, and discrediting cultural myths about mental health (Corrigan et al., 2012; Corrigan and Shapiro, 2010; Crowe et al., 2018; Evans-Lacko et al., 2012; Mak et al., 2014; Parcesepe and Cabassa, 2013; Wong et al., 2018).

Furthermore, online resources (e.g., more online literature about mental health, social support groups), peer services (e.g., people who have experienced the same mental health issues and can provide support), and policy changes to help protect individuals with mental illnesses (e.g., Americans with Disabilities Act), are recommended to help eradicate public stigma (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016). Implementation of these types of interventions, either alone or simultaneously, within collectivistic cultures such as Japan may help reduce the amount of public stigma individuals within those cultures have toward mental health illnesses and seeking professional help. Overall, it is recommended that interventions address both wide populations and specific target groups, as both help reduce public stigma.

As hypothesized, Japanese individuals had greater self-stigma than Americans. Since there is a strong connection between public stigma and self-stigma (Vogel et al., 2006, 2007), and since Japanese individuals in this study had greater public stigma, greater self-stigma was expected to follow. Moreover, self-stigma was greater for

both American and Japanese men than for American and Japanese women. This finding could be explained by gender differences. Previous researchers have found gender differences for intentions to seek help and have reported that men are less likely to seek help than women and even recommend self-care over seeking professional help (Haavik et al., 2017; Nam et al., 2010; Sen, 2004; Pattyn et al., 2015). This difference between men and women could also be due to men having more self-stigma about needing professional help for mental illnesses than women.

Researchers have found that masculinity ideology, masculine norms, and masculine gender-role conflict can discourage men from seeking professional help for mental health, and these factors ultimately promote avoidant behaviors toward seeking professional help (Addis and Mahalik, 2003; Cole and Ingram, 2019; Levant et al., 2009; Ramaeker and Petrie, 2019). Lynch et al. (2018) focused on barriers to seeking help that arose in a study of men. One theme was “traditional masculine ideals,” and men gave examples including the feeling that seeking help would compromise their masculinity, which was defined by self-reliance and strength. These qualities may be incompatible with disclosing one’s emotions, including negative feelings caused by mental illness, and can result in self-stigma. Another theme that appeared was “personal challenges,” which included examples of communication issues (e.g., difficulty communicating emotions), asking for help and then feeling a personal loss, and the inability to recognize the symptoms that coincide with mental illnesses. Both themes and the reasons listed correspond to masculinity ideologies and masculine gender roles, reflect previous research about men having less intention of seeking help than women, and can be classified as influencing self-stigma.

To reduce self-stigma, it would first be important to decrease public stigma since both types of stigma, while separate constructs, are highly related. To combat self-stigma, interventions have been implemented that are similar to the interventions used in reducing public stigma. Yanos et al. (2015) reviewed different psychoeducation programs to correct individuals’ current knowledge about mental health and to counteract any myths about the topic. Furthermore, cognitive techniques were reviewed, such as Narrative Enhancement and Cognitive Therapy (NECT). Yanos et al. (2015) discussed that NECT can promote learning the skills necessary to help individuals identify having self-stigma and combat their own negative thoughts and beliefs about mental health. Other researchers have designed and implemented programs such as the “Ending Self-Stigma” program (Lucksted et al., 2011). This program is nine weeks long and is tailored for individuals with serious mental illnesses. It helps reduce individuals’ self-stigma about mental illnesses, and individuals in this program have shown increases in personal strengths (Lucksted et al., 2011). Corrigan and Rao (2012) reiterated the importance of ensuring that individuals know that having self-stigma is not their fault, but rather a product of society. Corrigan and Rao (2012) emphasized utilizing the “Ending Self-Stigma” program and encouraged using it alongside peer support programs to reduce self-stigma. We recommend implementing the aforementioned interventions, based on their previous trials, to reduce the prevalence of self-stigma and to increase intentions to seek help.

In line with our hypothesis, Japanese individuals had less self-efficacy than Americans to overcome a mental illness with the help of a mental health professional. This could be due to the Japanese culture of showing modesty in public situations. In a study about accepting credit for prosocial behavior, American children viewed modest lies less favorably than Japanese children, and Japanese children were in favor of not taking credit for their prosocial behavior (Heyman et al., 2010). Other researchers reported that Americans tended to show self-enhancing tendencies, while Japanese individuals only showed self-enhancing tendencies when no reasons were present for making an evaluation (Yamagishi et al., 2012). Fu et al. (2011) found that people in individualist cultures were generally accepting of taking credit for doing good deeds while people in East Asian collectivistic cultures were not. Since Japanese populations have high levels of modesty, it could be that they are less likely than individualistic populations (e.g., Americans) to think they have the self-efficacy to overcome a mental illness. Therefore, Japanese individuals may attribute the success of overcoming a mental health illness to a professional instead of to themselves.

Gupta and Kumar (2010) found that self-efficacy was positively correlated with both mental health and one’s mood and suggested that self-efficacy be increased to help with one’s mental health status. Moreover, self-efficacy beliefs may determine if and how people motivate themselves (e.g., how one motivates oneself to seek professional help) and how they think about themselves (Andersson et al., 2014). This motivation, or lack thereof, may determine whether an individual seeks help. We recommend that motivation, along with one’s moods and attitudes about mental health and professionals, be increased among individuals for self-efficacy to be increased. Furthermore, diminishing stigma and improving mental health literacy among individuals could help increase self-efficacy (Andersson et al., 2014). Other researchers have recommended peer support services, structured interventions (e.g., motivational interviewing, cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment seeking), and creating health care services that ensure individuals seeking help know that treatment for mental illnesses is a positive opportunity (Johnson and Possemato, 2019).

In the present study, Japanese individuals had less intention to seek help than Americans did, and if individuals exhibited self-stigma, they were less likely to seek help. This finding can be attributed to this study’s findings that Japanese individuals have more public and self-stigma and less self-efficacy than Americans. To increase the intention to seek help, we recommend using the aforementioned interventions to decrease public and self-stigma and increase self-efficacy.

In addition to men having greater self-stigma, public stigma, and self-efficacy than women, there was also a gender difference in their confidence in the abilities of mental health professionals and in their intentions to seek help. Having more confidence in the abilities of mental health professionals was a positive predictor of seeking help for women, whereas it was a negative predictor for men. Although there were no hypotheses for gender, this finding corresponds to previous findings that women tend to have more positive attitudes toward seeking help (Efstathiou et al., 2019; Leong and Zachar, 1999; Masuda et al., 2005), and this could lead to women having more confidence in the abilities of mental health professionals.

There were some limitations to this study. All participants were college students, making these findings difficult to generalize to other age groups and settings. Moreover, there was a larger than average number of Caucasian participants in the American sample, making it difficult to generalize these findings to other races and ethnicities. However, this study had strong internal reliability within the measures used.

Many people never seek help, or they fail to fully engage themselves when they are seeking help for mental health illnesses (Corrigan, 2004). This could be due to the prevalence of high public and self-stigma and low self-efficacy. Therefore, multiple interventions have been suggested to reduce both public and self-stigma and to increase self-efficacy. Many studies on these topics have not been longitudinal, and future researchers should conduct longitudinal studies to examine the lasting effects of these interventions. It is further necessary to monitor any changes, both short and long term, in the societies in which these interventions are utilized. Interventions should also address gender differences when examining whether interventions increase intentions to seek professional mental health help. Interventions such as mass media campaigns, targeting groups with large amounts of mental illnesses, and programs like “Ending Self-Stigma” should be considered and implemented in areas such as schools, colleges, and the broader public to help reduce both public and self-stigma around seeking help for mental health problems.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Addis ME, Mahalik JR (2003). Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. American Psychologist 58(1):5-14.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Alamilla SG, Kim BSK, Walker T, Sisson FR (2017). Acculturation, enculturation, perceived racism, and psychological symptoms among Asian American college students. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development 45(1):37-65.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Andersson LMC, Moore CD, Hensing G, Krantz G, Staland-Nyman C (2014). General self-efficacy and its relationship to self-reported mental illness and barriers to care: A general population study. Community Mental Health Journal 50(6):721-728.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Atkinson DR, Gim RH (1989). Asian-American cultural identity and attitudes toward mental health services. Journal of Counseling Psychology 36(2):209-212.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bandura A (2006). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.). Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents 5(1):307-337.

|

|

|

|

|

Bandura A (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall, pp. 23-28.

|

|

|

|

|

Betz NE, Klein K, Taylor KM (1996). Evaluation of a short form of the Career Decision-Making Self-Efficacy Scale. Journal of Career Assessment 4:47-57.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cash TF, Begley PJ, McCown DA, Weise BC (1975). When counselors are heard but not seen: Initial impact of physical attractiveness. Journal of Counseling Psychology 22:273-279.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Chen JM, Kim HS, Sherman DK, Hashimoto T (2015). Cultural differences in support provision: The importance of relationship quality. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 41(11):1575-1589.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Chen SX, Chan W, Bond MH, Stewart SM (2006). The effects of self-efficacy and relationship harmony on depression across cultures: Applying level-oriented and structure-oriented analyses. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 37(6):643-658.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, Maggioni F, Evans-Lacko S, Bezborodovs N, Morgan C, Rüsch N, Brown, JS, Thornicroft G (2015). What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychological Medicine 45(1):11-27.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cole BP, Ingram PB (2019). Where do I turn for help? Gender role conflict, self- stigma, and college men's help-seeking for depression. Psychology of Men and Masculinities Advance online publication.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Corrigan PW (2004). How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist 59(7):614-625.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Corrigan PW, Bink AB, Schmidt A, Jones N, Rüsch N (2016). What is the impact of self-stigma? Loss of self-respect and the "why try" effect. Journal of Mental Health 25(1):10-15.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Corrigan PW, Morris SB, Michaels PJ, Rafacz JD, Rüsch N (2012). Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: A meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatric Services 63(10):963-973.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Corrigan PW, Rao D (2012). On the self-stigma of mental illness: Stages, disclosure, and strategies for change. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 57(8):464-469.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Corrigan PW, Shapiro JR (2010). Measuring the impact of programs that challenge the public stigma of mental illness. Clinical Psychology Review 30(8):907-922.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Barr L (2006). The self-stigma of mental illness: Implications for self-esteem and self-efficacy. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 25(9):875-884.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Crowe A, Mullen PR, Littlewood K (2018). Self-stigma, mental health literacy, and health outcomes in integrated care. Journal of Counseling and Development 96(3):267-277.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Efstathiou G, Kouvaraki E, Ploubidis G, Kalantzi-Azizi A (2019). Self-stigma, public-stigma and attitudes towards professional psychological help: Psychometric properties of the Greek version of three relevant questionnaires. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling 41(2):175-186.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Eden D, Granat-Flomin R (2000, April). Augmenting means efficacy to improve service performance among computer users [Paper presentation]. Annual Meeting of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, New Orleans, LA.

|

|

|

|

|

Evans-Lacko S, Brohan E, Mojtabai R, Thornicroft G (2012). Association between public views of mental illness and self-stigma among individuals with mental illness in 14 European countries. Psychological Medicine 42(8):1741-1752.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Fischer EH, Turner JL (1970). Orientations to seeking professional help: Development and research utility of an attitude. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 35(3):79-90.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Florer KJ (2015). The impact of self-efficacy, stigma, subjective distress, and practical factors affecting clients' intent to "no-show" [Master's thesis, Iowa State University]. Graduate Theses and Dissertations.

|

|

|

|

|

Fu G, Heyman GD, Lee K (2011). Reasoning about modesty among adolescents and adults in China and the U.S. Journal of Adolescence 34(4):599-608.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gronholm PC, Henderson C, Deb T, Thornicroft G (2017). Interventions to reduce discrimination and stigma: The state of the art. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 52(3):249-258.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gupta G, Kumar S (2010). Mental health in relation to emotional intelligence and self efficacy among college students. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology 36(1):61-67.

|

|

|

|

|

Haavik L, Joa I, Hatloy K, Stain HJ, Langeveld J (2017). Help seeking for mental health problems in an adolescent population: The effect of gender. Journal of Mental Health 28(5):467-474.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Han M, Pong H (2015). Mental health help-seeking behaviors among Asian American community college students: The effect of stigma, cultural barriers, and acculturation. Journal of College Student Development 56(1):1-14.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Heath PJ, Brenner RE, Lannin DG, Vogel DL (2018). Self-compassion moderates the relationship of perceived public and anticipated self-stigma of seeking help. Stigma and Health 3(1):65-68.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Heyman GD, Itakura S, Lee K (2010). Japanese and American children's reasoning about accepting credit for prosocial behavior. Social Development 20(1):171-184.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hui CH, Triandis HC (1986). Individualism-collectivism: A study of cross-cultural researchers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 17(2):225-248.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Inaba A, Thoits PA, Ueno K, Gove WR, Evenson RJ, Sloan M (2005). Depression in the United States and Japan: Gender, marital status, and SES patterns. Social Science and Medicine 61(11):2280-2292.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ishii K, Mojaverian T, Masuno K, Kim HS (2017). Cultural differences in motivation for seeking social support and the emotional consequences of receiving support: The role of influence and adjustment goals. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 48(9):1442-1456.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jaccard J, Wan CK, Turrisi R (1990). The detection and interpretation of interaction effects between continuous variables in multiple regression. Multivariate Behavioral Research 25(4):467-478.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Johnson EM, Possemato K (2019). Defining the things we can change to improve access to mental health care. Families, Systems and Health 37(3):195-205.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kasahara-Kiritani M, Matoba T, Kikuzawa S, Sakano J, Sugiyama K, Yamaki C, Mochizuki M, Yamazaki Y (2018). Public perceptions toward mental illness in Japan. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 35:55-60.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kikuzawa S, Pescosolido B, Kasahara-Kiritani M, Matoba T, Yamaki C, Sugiyama K (2019). Mental health care and the cultural toolboxes of the present-day Japanese population: Examining suggested patterns of care and their correlates. Social Science and Medicine 228:252-261.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kim BSK, Omizo MM (2005). Asian and European American cultural values, collective self-esteem, acculturative stress, cognitive flexibility, and general self-efficacy among Asian American college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology 52(3):412-419.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kim JE, Zane N (2016). Help-seeking intentions among Asian American and white American students in psychological distress: Application of the health belief model. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 22(3):311-321.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kiuchi A (2006). Independent and interdependent self-construals: Ramifications for a multicultural society. Japanese Psychological Research 48(1):1-16.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Koike S, Yamaguchi S, Ojio Y, Ohta K, Shimada T, Watanabe K, Thornicroft G, Ando S (2018). A randomised controlled trial of repeated filmed social contact on reducing mental illness-related stigma in young adults. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 27(2):199-208.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Komiya N, Good GE, Sherrod NB (2000). Emotional openness as a predictor of college students' attitudes toward seeking psychological help. Journal of Counseling Psychology 47(1):138-143.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kononovas K, Dallas T (2009). A cross-cultural comparison of perceived stress and self-efficacy across Japanese, U.S. and Lithuanian students. Psichologija 39:59-70.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lent RW, Brown SD (2006). On conceptualizing and assessing social cognitive constructs in career research: A measurement guide. Journal of Career Assessment 14(1):12-35.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Leong FTL, Zachar P (1999). Gender and opinions about mental illness as predictors of attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling 27(1):123-132.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Levant RF, Wimer DJ, Williams CM, Smalley KB, Noronha D (2009). The relationships between masculinity variables, health risk behaviors and attitudes toward seeking psychological help. International Journal of Men's Health 8(1):3-21.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Li J, Marbley AF, Bradley LJ, Lan W (2016). Attitudes toward seeking professional counseling services among Chinese international students: Acculturation, ethnic identity, and English proficiency. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development 44(1):65-76.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lucksted A, Drapalski A, Calmes C, Forbes C, DeForge B, Boyd J (2011). Ending self-stigma: Pilot evaluation of a new intervention to reduce internalized stigma among people with mental illnesses. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 35(1):51-54.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lynch L, Long M, Moorhead A (2018). Young men, help-seeking, and mental health services: Exploring barriers and solutions. American Journal of Men's Health 12(1):138-149.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mak WWS, Chong ESK, Wong CCY (2014). Beyond attributions: Understanding public stigma of mental illness with the common sense model. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 84(2):173-181.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Markus HR, Kitayama S (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review 98(2):224-253.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Masuda A, Boone MS (2011). Mental health stigma, self-concealment, and help-seeking attitudes among Asian American and European American college students with no help-seeking experience. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling 33(4):266-279.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Masuda A, Suzumura K, Beauchamp KL, Howells GN, Clay C (2005). United States and Japanese college students' attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. International Journal of Psychology 40(5):303-313.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mojaverian T, Hashimoto T, Kim HS (2013). Cultural differences in professional help seeking: A comparison of Japan and the U.S. Frontiers in Psychology 3:615.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Nam SK, Chu HJ, Lee MK, Lee JH, Kim N, Lee SM (2010). A meta-analysis of gender differences in attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. Journal of American College Health 59(2):110-116.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2016). Ending discrimination against people with mental and substance use disorders: The evidence for stigma change. The National Academies Press.

|

|

|

|

|

O'Connor PJ, Martin B, Weeks CS, Ong L (2014). Factors that influence young people's mental health help-seeking behaviour: A study based on the Health Belief Model. Journal of Advanced Nursing 70(11):2577-2587.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Parcesepe AM, Cabassa LJ (2013). Public stigma of mental illness in the United States: A systematic literature review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services 40(5):384-399.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Pattyn E, Verhaeghe M, Bracke P (2015). The gender gap in mental health service use. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 50(7):1089-1095.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ramaeker J, Petrie TA (2019). "Man up!": Exploring intersections of sport participation, masculinity, psychological distress, and help-seeking attitudes and intentions. Psychology of Men and Masculinities 20(4):515-527.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Saavedra J, Arias-Sánchez S, Corrigan P, López M (2020). Assessing the factorial structure of the mental illness public stigma in Spain. Disability and Rehabilitation 1-7.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sen B (2004). Adolescent propensity for depressed mood and help seeking: Race and gender differences. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 7(3):133-145.

|

|

|

|

|

Shimotsu S, Horikawa N, Emura R, Ishikawa S-I, Nagao A, Ogata A, Hiejima S, Hosomi J (2014). Effectiveness of group cognitive-behavioral therapy in reducing self-stigma in Japanese psychiatric patients. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 10:39-44.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Solberg VS, Good GE, Nord D, Holm C, Hohner R, Zima N, Heffernan M, Malen A (1994). Assessing career search expectations: Development and validation of the career search efficacy scale. Journal of Career Assessment 2(2):111-123.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Su LP, Miller RB, Canlas JM, Li T-S, Hsiao Y-L, Willoughby BJ (2015). A cross-cultural study of perceived marital problems in Taiwan and the United States. Contemporary Family Theory 37:165-175.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sun S, Hoyt WT, Brockberg D, Lam J, Tiwari D (2016). Acculturation and enculturation as predictors of psychological help-seeking attitudes (HSAs) among racial and ethnic minorities: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Counseling Psychology 63(6):617-632.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Suryaningrum C (2018). The correlation of self-construal, self-efficacy, and emotional regulation strategy as cultural factors with social anxiety: Preliminary study. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research 133:206-211.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Taylor SE, Sherman DK, Kim HS, Jarcho J, Takagi K, Dunagan MS (2004). Culture and social support: Who seeks it and why? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 87(3):354-362.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Vogel DL, Bitman RL, Hammer JH, Wade NG (2013). Is stigma internalized? The longitudinal impact of public stigma on self-stigma. Journal of Counseling Psychology 60(2):311-316.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Vogel DL, Strass HA, Heath PJ, Al-Darmaki FR, Armstrong PI, Baptista MN, Brenner RE, Gonçalves M, Lannin DG, Liao H-Y, Mackenzie CS, Mak WWS, Rubin M, Topkaya N, Wade NG, Wang Y-F, Zlati A (2017). Stigma of seeking psychological services: Examining college students across ten countries/regions. The Counseling Psychologist 45(2):170-192.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Vogel DL, Wade NG, Haake S (2006). Measuring the self-stigma associated with seeking psychological help. Journal of Counseling Psychology 53(3):325-337.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Vogel DL, Wade NG, Hackler AH (2007). Perceived public stigma and the willingness to seek counseling: The mediating roles of self-stigma and attitudes toward counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology 54(1):40-50.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Wang S, Lau AS (2015). Mutual and non-mutual social support: Cultural differences in the psychological, behavioral, and biological effects of support seeking. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 46(7):916-929.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Wong EC, Collins RL, Cerully JL, Yu JW, Seelam R (2018). Effects of contact-based mental illness stigma reduction programs: Age, gender, and Asian, Latino, and White American differences. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 53(3):299-308.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Yamagishi T, Hashimoto H, Cook KS, Kiyonari T, Shinada M, Mifune N, Inukai K, Takagishi H, Horita Y, Li Y (2012). Modesty in self-presentation: A comparison between the USA and Japan. Asian Journal of Social Psychology 15(1):60-68.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Yamawaki N, Pulsipher C, Moses JD, Rasmuse KR, Ringger KA (2011). Predictors of negative attitudes toward mental health services: A general population study in Japan. The European Journal of Psychiatry 25(2).

|

|

|

|

|

Yanos PT, Lucksted A, Drapalski AL, Roe D, Lysaker P (2015). Interventions targeting mental health self-stigma: A review and comparison. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 38(2):171-178.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Yıldız IG, ÅžimÅŸek ÖF (2016). Different pathways from transformational leadership to job satisfaction: The competing mediator roles of trust and self-efficacy. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 27(1):59-77.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Yoshioka K, Reavley NJ, Rossetto A, Nakane Y (2016). Associations between beliefs about the causes of mental disorders and stigmatizing attitudes: Results of a mental health literacy and stigma survey of the Japanese public. International Journal of Mental Health 45(3):183-192.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Zartaloudi A, Madianos MG (2010). Mental health treatment fearfulness and help-seeking. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 31(10):662-669.

Crossref

|

|