Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

This paper presents the phenomenology of Issa-Afar protracted violence in Ethiopia from hitherto unexplored vintage points of remembering (subjective memory), re-presentation (narrative construction and re-construction of remembering), and dramaturgy (the discursive and performative utility) of violence. Issa-Afar violent conflict is one of the most protracted violent conflicts in the Horn of Africa that unabatedly perpetuated at least since the turn of 20th century to date. Situated at the cross-roads of the most insecure, fragile and geo-strategically significant region of the Horn characterized by Regional Security Complex, and the environmentally and historically marginalized pastoral territories of Ethiopia, Issa-Afar protracted violent conflict is checkered with local, national, regional and global interplay of forces; the complex overlap of identity, politics, geography and history have set the context and dynamics of perpetual violence. The study strongly contends that the unattended continuity of memories of violence, the remembering, representation and dramaturgy involved have contributed to the self-perpetuation of violence; and strongly recommends to re-tune state and none state efforts to address the invisible and visible, consequential and inconsequential utilities of Issa-Afar conflict in a synchronic orientation. The paper has purely qualitative research design and exploratory analytical approach which is based on the collection and analyses of huge qualitative data from triangulated data collection tools covering eight decades. Primary data sources were gathered from Afar, Issa, Oromo and federal organ informants; secondary archives of the three successive governments accessed are from Afar, Somali, Harari and Dire Dawa administrative organs, as well as Central (Federal) government archives at Addis Ababa. Theories of protracted violent conflict (from peace studies), dramaturgy of violence (from sociology) and memory and representation of violence (from Hierological history and anthropology) are triangulated under the umbrella of Constructive Conflict Transformation; theories are embedded in the main body as triangulated frame of analyses. The paper is organized into four parts; part one provides prefatory note; part two describes the prognosis of the conflict; part three analyses memories, narrations and representation of violence based on critical reflections on popular beliefs, official evidences and historical documents and informant narrations; part four presents the complex impact of remembering and representation in molding the dramaturgical shift of recent Issa-Afar violence; the last part makes brief remarks as conclusion and recommendation.

Key words: Issa-Afar, remembering, representation, dramaturgy, trauma, victimization.

INTRODUCTION

The Issa and the Afar belong to the southern Cushitic linguistic category of the Somali and Afar speaking Horn of Africa respectively. The Issa are one of the nine Somali clans residing in Ethiopia, Djibouti and Somali-land (Schrader, 1993); the Afar, a distinct ethnic group, are ancient settlers in Ethiopia, Djibouti and Eritrea (Gemaludin, 2007). This study, though not exclusively, is concerned about the Issa-Afar violent conflict in Ethiopia. Issa-Afar conflict is the most protracted and intractable violent communal conflict in the Horn of Africa (Markakis, 2003). The tempo of violence has never shown significant de-escalation since the turn of the 20th century to date; nor does current state of affairs harbor faint hopes in the horizon of the future. This accounts for the structural, cultural and direct violence constituted and instituted through the long history of violence and interplay of complex overlap of multi-tiered factors. The conflict, despite the nature of changes, has been feeding on positive and negative local, national, regional and international changes towards further escalation: it became resistant to positive change. Comprehensive understanding of how the Issa and Afar bogged down in self perpetuating cycle of violence is examined here from the vintage point of remembering and representation of memories of violence and the unfolding transformation of the expression of violence.

METHODOLOGY

The paper has purely qualitative research design and exploratory-critical analytical approach which is based on the collection and analyses of huge qualitative data from triangulated data collection tools covering eight decades. Primary data sources are gathered from Afar, Issa, Oromo and federal organ informants; secondary archives of the three successive governments accessed are from Afar, Somali, Harari and Dire Dawa administrative organs, as well as Central (Federal) government archives at Addis Ababa. Theories of protracted violent conflict (from peace studies), dramaturgy of violence (from sociology) and memory and representation of violence (from Heterological history and anthropology) are triangulated under the umbrella of Constructive Conflict Trans-formation; theories are embedded in the main body as triangulated frame of analyses.

History as battle ground of the Nowhere and Arrivant

Examining the nature of contemporary Issa-Afar violence requires turnedness (Wsphycogrod, 2001:49-51), retro-active look to the past. To capture the current (nowhere) and future (Arrivant) dynamics of the violent conflict, it is mandatory to explore the past, where it all began or is imagined to have in the collective-archive of communal memories. To comprehend the dominant role of oral tradition and folklores among the Afar and the Issa in presenting and re-presenting the memory of violence in the Nowhere and preserving it to the Arrivant, it is commendable to put oneself in the feet of ‘the angel of history’ (Anderson, 2006:161-62)[1] of Issa-Afar Violence; oblivious of stream of events, frozen captive of and transfixed by history of violence ever regressing in evermore progressing piles of wreckage.

Accordingly, Issa-Afar conflict is rooted in Issa-Afar shared and rival Mythogenesis; shared communal myth has it that, the Issa and Afar claim descent from the first ancestor to settle the planet. Rivaling myths begin in the prototype narrative of conflict and separation of brothers and the consequent formation of mutual-incriminatory Othering in biblical story of the Prodigal son; but in this case the cursed unrepentant other. The Afar version has it that ancestor of the Issa selfishly usurped the cattle inheritance denying his brother his fair share and was cursed to live in barbarity of wilderness. The narration goes on to define contemporary Issa violence genetic inheritance of the cursed other (Mohammed, 2009). The Issa version states that on separation ancestor of the Afar settled in fertile and hospitable banks of the Awash and Erer, his unfortunate brother led for long precarious existence of the wilderness; facing extinction, he requested to take refuge in the Aden of his brother, which the latter ungratefully denied him to doom. The conflict that began by malicious cruelty of the Afar ancestor has continued to date in his offspring’s continued continuity of cruel judgment to Issa extinction in wilderness (Hirsi, 2009).

The same rivalry over myth and history encapsulated the re-presentation of latter historical cataclysms, among others the Harrela (ETV, February 19, 2008) extinction, the persona, victory, defeat and succession of Imam Ahmed Ibrahim Algazi (the left-handed), and the demise of the Adal Sultanate. According to the Issa myth, the Harrela were the South Eastern dwelling Afar, whose unsleeping malice and abuse of their God given wealth and power consummated their annihilation (Shukri, 2009). The Afar, on the other hand, accept the myth of their might, wealth and Afar identity to support their historical presence and territorial claim over the environs of Dire Dawa and Harerge highland (Historical Harrela Homeland) before their eviction by waves of successive Issa invasion during the first half of the 20th century; yet, they characterize the Harrela cataclysm to unfathomable super natural power doing (Hamedu, 2009). The rivaling myths of origin, instead of the myth of the Harrela cataclysm, applies in explaining the two fiercest warring Issa and Afar clans named Harrela; the two namesake clans are believed to have been formed after process of segmentary lineage (Duany, 1993).

On the other hand, both groups claim over the Persona of the Imam, his great victory and the right to succession to their own while they do mutual incrimination for the eventual defeat of the multi-ethnic army of Imam Ahmed to each others’ malice and weakness (Gemaludin, 2007:288; Yasin, 2008:39). The Afar who succeeded to inherit Adal sultanate and formed the powerful Awusa Sultanate in the homeland of the Aydahiso moving their center from Hararge Highland to the fertile bank of lower Awash basin were, to the Issa, usurpers whose absolute tyranny caused their eventual distraction (Roble, 2009; Musa, 2010; Mayru, 2010).[2] Among mainly the Awusa Afar, the demise of the Sultanate is widely held to have been caused by persistent Issa invasion from the South (Yayo, 2010; Ahmed, 2010).

The same structure of representation of the past has defined their relation to the Ethiopian Empire. For the Afar, the Issa are opportunist diabolical other always working for the destruction of the Afar homeland and Ethiopia in time of the political weakness and sickness at the center and external enemy presence at the gates (Mohamed, 2010). [3] On the other hand, they depict the unwavering patriotic vigilance of the Afar people for Ethiopian sovereignty from the times of the massacre of Italians by Sulatan Elelta (Great) Mohamed, through Sultan Ali Mirah up to now (Ethiopian Review, 1992).[4] The Issa narrative depicts the Afar as malicious in manipulating Ethiopian state interests for their gain at the tribulation of the Issa in the hand of successive governments’ punitive military campaigns, drought and famine. They vehemently regret how Ethiopian govern-ments always fail to see Afar schema of resurrecting the zombie of the Gragn syndrome, the Achilles hill mot contemporary but Imperial Ethiopian, to realize their long term hidden Greater-Afar (in Afaraff known as Siddocamo, Afar Triangle) aspiration. Issa counter out maneuvering similarly harped on the same string of manipulating national security interests of Afar- Horn states (Ethiopia, Eritrea and Djibouti) that the Siddocamo aspiration is grave reconfiguration and harbinger of evil to the horn states; that Issa strong presence in Ethiopia and Djibouti is vital to checkmate the danger of Greater Afar (IAJC, 1999). The mutual conspiracy theories have often succeeded in causing misery on both sides of the divide. Yet, Issa power coefficient in the regional power equation has grown asymmetrically mainly availing internal and regional developments in Afar-Horn states that continuously left the Afar weaker than ever.

The manipulation, selection, re-casting, reconstitution and re-presentation of historical collective memories for pragmatic gains of the present (the Nowhere) and future strategic subjective aspirations and averting real and imagined threats (the Arrivant) have made history the battle ground of communal and state actors. In effect, the role of structural, cultural and direct violence perpetuating narratives and structures of re-presentation has unleash-ed the plague of grotesque turnedness animating state and communal actors towards violent behavior. The overall imperative to addressing immediate basic human needs, reducing violence and enlarging justice (Leaderach, 2003), in agile and creative turnedness towards history with practical attendance to the Nowhere (Wsphycogrod, 2001) and vigilant envisioning of the future horizon is kept hostage of the memory, re-membering and representation of violence.

In light of this, the socio-cultural values and practices of pastoral egalitarianism, even more, the steady fast social and informational network of consensual and universal thought structure among the Afar and the Issa is synonymous of totalitarian indoctrination in violent values; the precarious pastoral daily life provides practical confirmations and re-affirmation of hate, enemy imagery and violence in all forms, for all utility and disutility: baptism in violence. The experiential and operational rationales of violence under the animating spell of the subjective Turnedness which are made to be the unlived presence of the absent (John, 2001) in productive and reproductive constellations of society become part of the super-structure as symbolic significance of society. This seemingly abstract transformation of violence rooted in history into symbolic existence to which individuals unconsciously comply, live in and die of is given material existence by real life experiences of violence; an outcome of un dealt matter-the shadow-often erroneously inferred as ‘evidences’-of being violent- for sticking to recantation of violent memories; the unattended truth behind being violent in attitude and behavior is embedded in structural continuities-Epicenters as much as mediated by distressing Episodes. One of the many overlooked epicenters is the memories of violent episodes, the structures of remembering and representation involved. The mutual causation of the violent epicenters and episodes, and their remembering and representation perpetuates violence. Among the major structures sustaining violence, the study cruises through the unchartered territory of memories of violence.

[1]Walter Benjamin’s grotesque image of the Angel of History true image of the tragic Issa-Afar predicament except that for the latter the angel pretends conscious of pattern of events and in vain manipulates them to ensure progress, which Benjamin’s Angel is oblivious about, but both adding obscene banality of violence. He wrote that, ‘His face is turned towards the past. Where we perceive a chain of events he sees one single catastrophe which keeps pilling wreckage up on wreckage and hurls in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm is irresistibly propels him in to the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we called progress.' P.p.: 161-62.

[2]Among the Afar the political degeneration introduced by the Awusa Sultanate is known as decadence from the House of Authority by law (Mada’a Xinto Buxxa) to the despotic Oligarchy of Sword (Gile Xinto Merra).

[3]Also see Mu’uz Gidey’s Issa-Afar Conflict in Post-1991 Period.

[4]The verbatim of the last Sultan of Awusa AliMirah Hanfere ‘Even our camels know the flag of Ethiopia’ had strong emotional appeal to the mass and the permanent siege mentality of whoever leader be at the center are partly connected with the above narration and mainly the old stance to realize greater Afar aspiration within Ethiopia.

ISSA-AFAR REMEMBERING AND RE-PRESENTATION OF MEMORIES OF VIOLENCE

“Memory is a festering wound”

(F. Nietzsche, Ecce Homo)

“. . . for it is a fact that humans shape

their memories to suit their sufferings.”

(Thucydides)

“. . . as is commonly said by people,

memory must be the guardian of lies.”

(Optatus)

Studies on post-war societies in Africa and Latin America have shown that memory of victimhood and violence is inextricably embedded in the mind of not only those directly involved as victim and perpetrator but also in the mind of passive audience. The memory of trauma and victimization is transmitted and shared with people not involved in any one of the three ways by narrations of violent stories. The themes in the epigraphs are instructive of examining stories of victimhood and trauma that are recreated fitting into subjective narrative structures (Thucydides) corresponding to peculiarities of every historical period, in extreme cases verging the trickster in true form, fabrication of lies (Optatus). Hence, the representation of communal remembering of memories of violence reconstructed and sustained in the present and future.

Survey of communal Memory of victimhood and trauma has exhibited universality among the Afar and the Issa, polar opposite of atomies societies (violently individualistic), precluding individuation (violently communitarian) at any level (Galtung, 2003:61). Even children are not immune from the destructive acumen of transgenerational memories of victimhood and trauma remembered and re-presented bourgeoning violent symbolism in time and space. The dangerousness of this remembering is associated with ‘the simultaneously collective forgetting . . . (of) its historical recency, . . . (so does of) forgetting the violence which brought them into existence…’ (Gebrewold, 2009) that keeps hostage the present (Nowhere) and future (Arrivant) to the dark images of memory. To further elucidate this point in Issa-Afar history of violence, major collective and individual memories of victimization embedded in Issa-Afar historical episodes of direct violence are discussed in historical chronology.

For availability of recorded official accounts, Issa-Afar violent conflict dynamics is discussed from the period of Italian invasion to date. Survey of official documents beginning from the pre-Italian invasion shows that despite various peacemaking efforts by successive Ethiopian governments, Issa-Afar violent conflict has remained impregnable to change. During the Imperial government of Hailessilassie, Issa-Afar violent conflict was mainly owing to cultural and resource competition factors common to pastoral mode of production and the universal ecology-conflict linkage characterizing most contempora-ry African pastoral societies. Conflict situation and incident reports for the period 1934-1974 have recorded hundreds of Issa-Afar raids and counter raids in the Harerge and Erer highlands that left thousands of human causality, hundreds of thousands of cattle rustled, villages and hamlets razed to the ground. The Issa evicted the Afar locality after locality, except for temporary halt and relapse of the tide of violence to the former, pushing the latter down hills of the traditional Issa-Afar divide of Erer River to the Awash valley (Dawa, 26/01/46; HGGO, 26/01/46; VHGG, 17/10/49). Before the Italian invasion in 1935, the Imperial government followed punitive and conciliator hybrid strategies of containment judging the violent conflict, as was the dominant thinking of the time, inherent of Issa-Afar culture and nomadic social organization (MoI Department of Public Safety and Security (MoI-PSS, 15/08/1960). The government acted with contempt as neutral arbiter between its uncivilized (other) barbarous subjects characteristic of Christian-Highlander Ethiopian political culture with its deeply embedded memory of the Gragn syndrome and staunch view of pastoral territory as terra nullius (HGGO, 1945-74; AIKW, 20/02/46-1956; MoP, 1946; AIGO, 20/02/46- 1956). Since the nature of conflict during this period was mainly due to cultural and resource causes and was less resistant to state and customary containment measures, it was not utter state misconception. Afar and Issa elders similarly remember the period (recasting against current state of crisis) as the good old days where state was effective as neutral arbiter and Issa-Afar customary conflict resolution constellations were functionally effective in containing violence (Yayo, 2006; Tahiro, 2008). However, objectively speaking official records of the frequency of violent over turns and effectiveness of containment measures of the period witness the good old days were not good enough in containing direct violence rooted in culture and fragile ecological structures. During the period, in particular the years 1931-1935, no month had passed without recording at least two failed containment measures and fresh outbreak of violent clashes (Mu’uz, 2010). On the other hand, taking the organization of violence (instruments, mobilization and short period of active violent clashes) but the consequences thereof, the good old days were not totally the bad days; more so compared to the transformation of the nature, objectives and organization of violence during Italian occupation and thereafter.

The Italian occupation had as much influence on the transformation of Issa-Afar violent conflict as on the post-restoration political dynamics in Ethiopia. Before this period, despite the presence of colonial powers in the Afar-Horn and Somali-Horn, Issa-Afar violent conflict had not been directly linked with the precarious and fragile sovereign status of the Ethiopian state. This is evident from the orientation of the Imperial government towards the conflict discussed above (MoP, 1946). Up until the post-restoration period National Intelligence and army reports had not linked Issa-Afar violent conflict with big power and sub-regional national security threats. Nor did it appear in Afar and Issa collective memory of the past and the narrative structure of representation of the history of Issa-Afar violence (MoP, 1946).

The Italian occupation period

The brief discontinuity of Ethiopian state sovereignty during the Italian occupation had introduced new elements to Issa-Afar Violence once considered by both conflictants and state actors as ordinary pastoral communal violent conflict over resources and values.

First, the Italian effort to co-opt and manipulate historically marginalized religious and ethnic groups’ support during the invasion and occupation, the Issa and the Afar being Muslim and pastoral were victim of double marginalization, among the most favored targets. Based on the level of allegiance and resistance each group pledged to the new master the binary patriot-traitor (equivalent in Amharic to Arbegna ena Banda) fault line that divided post-restoration national politics was introduced into Issa-Afar conflict as powerful political variable (HGGO, 9/1/44; AIWG, 18/04/47; HAGOR, 1/9/47). Second, the introduction of stoke piles of gun power during the occupation as part of the reward for loyalty to the occupying force and as part of the partisan patriotic resistance changed Issa-Afar violence in two ways: the organization of violence and power relations. The availability of semi-automatic and automatic light and heavy weapons with ample supply of ammunitions changed the objectives, mode of organization, duration and frequency, and the impact of warfare among the Issa and the Afar. Hitherto violent clashes using rudimentary implements of warfare carried out in spontaneity and that only lasted for very few hours, a day or couple of days now using individual and group gun power fashioning regular military formation raged for weeks leaving unheard of cataclysm behind every violent incidents; securing access to water point, grazing land and settling old scores, vengeance and trophy killing that characterized pre-occupation violence were replaced by objectives of total eviction and permanent territorial occupation verging mutual extermination (AIWGO, 5/7/39; AIWGOR, 5/7/39). The influx of gun power in Issa society by the Italians in return for their active loyalty as opposed to Afar resistance and reluctance ushered power asymmetry in the most vital implement of violence that in turn determined the nature and organization of violence in favor of the Issa. Given the high value attached to gun among the Afar and the Issa, the mutated escalation of communal violence threatening communal security got the best of both groups snared in gun-violence cycle(Ibid). The seed of self-perpetuating violence that further hardens intractability of conflicts in a context of unmitigated power asymmetry was sawn during this period. Third, stories of massacre, massive eviction and territorial, annexation discussed at length in the next sub-section, that reverberates across ages since then to date in shaping the RRD of Issa-Afar history of violence began to take shape. The advent and use of hand grenades and other explosives for the first time in the history of not only among the Issa and the Afar but also among Oromo and Gedebursi clans was introduced during this period. The Italians brought unprecedented destructive capability never used even by then except in Issa-Afar violence (Tekole, 2008). Archival sources of the Italian occupation period showed the scale, immensity, frequency and organization of Issa-Afar violence reached crisis level to be critical security concern of the occupying force that it desperately resorted to play the role of neutral arbiter; showing no de-escalation to contain the cycle of violence in the face of relentless patriotic resistance, the occupying force hinged on empowering the utility of customary conflict resolution constellations. Yet, despite very short lived relief Issa-Afar violence continued gathering destructive momentum during the periods of occupation, post-restoration and thereafter (HGGO, 1935/6). Fourth, the occupation could also be taken the first school for both the Issa and the Afar to learn the active art of violent politicking and politicking of violence that continued during the post-restoration through the Dergue to date. This is evident from the systematized mutual incrimination campaigns both groups launched immediately after the restoration of the monarchy (Mu’uz, 2010). Finally, the relative experience of empowerment of traditional leaders and ease of domination of society by the Italians, typical divide and rule tentative colonial schema, on the one hand and the disgrace and eventual forced exile of the monarchy on the other hand added element of contempt, manipulation and defiance against the latter in post restoration period (Ibid). Consequently, the cumulative impact of the brief experience of Italian occupation relayed Issa-Afar violence from quagmire in to Calderon in post restoration period.

Post-restoration period

The grotesque restored monarchy and the precarious struggle and not yet won battle for territorial integrity and national sovereignty in the post-restoration British dominance period at home and ex-Italian colonies gave Issa-Afar violence regional dimension. The inability of reestablishing effective local administration in Afar-Issa homelands, and the challenge of unifying the national post-war divide, restoring old territories under British control and the sub-regional challenge of emergent Somali nationalism put Issa-Afar violence once more at the heart of national and regional politics (Government, 12/5/48; AIAG, 30/1/53; GTW, 29/2/53; JAGO, 29/2/53; AIAGO, 23/11/52; AIAGO, 'Crisis Report of the nomadic Issa has caused on us', 8/11/52; AIAO, 2/12/52). In effect, the immediate post-restoration period local, national and regional contexts let loose all evils of Issa-Afar violence that made it national security concern. According to Imperial government Ministry of Public Security (MoPS) records, Issa-Afar violent conflict had been rated number one national security threat from the Eastern and South Eastern direction (Ibid). Conscious of the precarious situation both groups meticulously attempted to manipulate government security concerns in their favor that furthered the tempo of violent escalation. The restored monarchy pursued an eclectic approach of coercion, conciliation, containment and checkmating of the conflicting parties. Unfortunately, none proved effective that as part of the national administrative reshuffling of old administrative structures, different administrative structures involving the juxtaposition of Issa, Adal, Karrayu, Gedebursi and other identity groups were tried with no lasting containment on Issa-Afar violent interface (Ibid). Nor did the various conciliatory as well as military punitive measures do any better.

Somalia irredentism

The emergence of Somali nationalism and its irredentists Greater Somalia Project up on independence in 1960 further augmented the precarious national security status that in turn complicated Issa-Afar violent conflict linkage with internal and external (sub-regional) forces. The local-regional nexus of Issa-Afar violence and its politicking had never been seen in full shape until the two Somali invasions wherein the Issa cause merged with Somalia irredentism and the Afar cause carried the banner of Ethiopian state nationalism. This was openly debated in central government mediated Issa-Afar conference during both periods. The imperial government until its demise by the popular revolution continued to checkmate the Issa and the Afar only for ensuring national security concerns. Except the unsuccessful coercive attempt to disarm the Issa and arm the Afar during the immediate post-Somali invasion period no substantial measure had been taken to change the asymmetry introduced during the Italian occupation (Ibid).

Revolution, war and independence

The PMGE and latter on the PDRE government except for dose of military measures on both Issa and the Afar it did followed no different orientation from its predecessor. The Somalia invasion accompanying the revolution and the independence of Djibouti under the leadership of Issa dominated government (to the dismay of the Afar) further cemented its national and military security orientation of the military government committed to solve not only Issa-Afar conflict but also the civil war at national level. The presence of Somali and Afar ethno-nationalist armed dissident groups gave legitimacy to its intransigency on using heavy handed management of Issa-Afar violence. Add to it Issa-Afar politicking to manipulate government security concerns to their benefit which did achieve any substantial gain for none other than tightening the grip of the military administration put in place since the era of the monarchy (PSSO, 25/11/52; CCTTD, 12/1/960; PMGSE, 6 Feb, 1987).

In short, the Dergue with the view of securing the rail and life line to Djibouti and Assab respectively forcefully imposed faring and disarming both groups from these vital infrastructures and the state farms and agricultural schemes introduced during the past regime and further expanded by it. Thus, the Dergue left the Issa and the Afar to their violent discretion provided that they would not be nuance to its security and military concerns (Ibid). Yet, it does not mean that there were many unsuccessful peacemaking efforts and unfulfilled promised; nevertheless, none were of any genuine concern for envisioning non-ephemeral lasting settlement in the benefit of the people than for short sighted military-security considerations (Ibid).

The mill of Issa-Afar violence kept on grinding and gathering ever more intense memory of violence, expanding the stories of eviction and mutual bloodletting from Hararge highland, through the Awash valley up to the hinter land of traditional Afar homeland on the tarmac road leading to Assab and Djibouti (MoFA, 1995-2010). However, it would be unfair to miss the dominant perception among the Afar and the Issa that despite barbaric measures the Dergue in comparisons with its predecessor and successor had limited the spiral of violence (ASJAB, Issa-Afar Joint Peace (IAJP) Conference Reports, 2007-2008; FGD, 2010; FGD, 2010). This communal perception is instructive of the lesson that shared victimization in the hand of unrepentant tyranny could create mutually accepted views by groups engulfed in history of violence as the Afar and the Issa. Yet, it is also worth noting that such binding views are powerless in the face of historically accumulated communal memories of enemy imagery, hatred and violent narratives that seldom spared divergent and convergent views from the instrumentation for the grand narrative of victim hood. This is evident from the mutual-demonizing re-presentation of their shared myth of origin, ties and religion, as well as historical events to fit their contemporary image of the cruel other. More particularly, mutual incrimination of manipulating the Dergue to cause misery against respective community is popular among both the Issa and the Afar (Md, 2008).

Post-1991 Period: Old wars and New Wars

The EPRDF upon coming to power inherited Issa-Afar violent conflict along with its unabated escalation, ever growing and changing issues debilitating the challenge of solving the old with the rise of new issues accompanying the outbreak of every violent incident. However, there are also new developments contributing to complete trans-formation that accounts to the new national, regional and local contexts of the restructuring of state and society in post-Dergue Ethiopia which requires brief exploration.

To begin with the global and regional dynamics, follow-ing the collapse of the USSR power block and the end of the Cold War, the Horn of Africa experienced multiple changes affecting the structure and content of states and societies. The gradual descent of Somalia from peacelessness into statelessness, the downfall of the Dergue and the de facto secession of Eritrea, and the outbreak of civil war in Djibouti were among major changes in the region that had close implications on Issa-Afar conflict dynamics. Though the rest of the world was jubilant in coming out of the Cold, Africa in general and the Horn in particular was still trapped in the uncertainties of post-war political transition, outbreak of fresh civil war and spontaneous eruption of communal violence. In Ethiopia, besides the former Ethiopian army soldiers and the victorious EPRDF, there were more than dozens of ethno-nationalist armed groups; among which three Afar and two Somali armed groups were active in the political scene (Ibid) (HF, 2008).

The region and the Afar and Somali Horn in particular was flooded with SALWs left over of the Cold War and the excess stoke piles of armed produced for but not supplied during the Cold War provided fresh supplies from big powers. The Issa and the Afar were armed to their tooth from domestic and external inflows. In both Awusa and Jigjiga former armed groups are battling for dominance as much as the struggle at the national political arena on structural issues for and against self determination and secession of the Ogaden Somali region of Ethiopia and the Southern Red Sea coastal Afar homeland of Assab. The EPRDF block at the central had not had effective control over Afar and Somali regions as much as it was not until much later able to forge non-ephemeral structure of representation (Ibid). In the mean time, the Afar and the Issa anticipating proactive out maneuvering got locked in violent clashes; this time with the support and involvement of armed groups rallying divergent agendas ranging from irredentist reunification, secession and against further separation of the Red sea Afar up to and including national unity. Both sides got ample political tramp cards for mutual subversive politicking as much as continuing their goals by violent means.

During the transitional period and the beginning of the federation, despite the promise on the part of EPRDF led government for peaceful and lasting settlement, intermittent violence continued with further territorial gains on the Issa side. The Afar though for the first time united under their own self governing region and the Issa equivalent to their population and territory only zonal administrative unit at Shenile within the Somali region; however, it did not change the historical power asymmetry. In effect, in the first five years after the downfall of the Dergue, the Issa controlled more territories than they had in thirty years (Mu’uz, 2010). According to some observers, this was due to the political factors associated with self determination and the undetermined ethno-territorial administrative boundary demarcation left in limbo since then to date. Since self determination is unrealizable without effective control over feasible territory and the administrative boundary demarcation equation in order to avoid tumultuous historical claims and counter claims has avoided historical claims the like of the Afar, the Issa vehemently perused territorial annexation and subsequent demand for recognition. The Afar, on the other hand, made various counter moves to restore new and old lost territories only to give Issa pretext for further penetration that brought the latter at the current hot spots at Adaytu, Gedamaytu, Qunduffo and very recently at the door steps of Mille (Ibid).

At the political front the Afar harped on the old over used Greater Somali threat narrative to win the favor of the federal government; the presence of certain Somali political parties with secessionist agenda was capitalized to establish that Issa invasion of the Afar was part of the Grand Somali project of dismembering every territory the Somali set its feet on (ESDM, 1992). On the other hand, the Afar popular resistance against the dismemberment of the Assab region with Eritrea, the rise of an all-Afar war lead by FRUED against the Issa dominated government in Djibouti and the continued presence of unrepentant armed Afar nationalist movements against all Afar-Horn states (Ethiopia, Eritrea and Djibouti) for the realization of the so called Siddoccaho (the Unified Afar Triangle) aspiration was counterproductive to the Afar cause. It instead became a readymade effective weapon for the Issa (to score huge political gains) against the Afar. Moreover, the Siddoccaho aspiration its feasibility notwithstanding, caused the Afar to be at best less attractive, at the worst harbinger of sub-regional destabilization in the eye Eritrea and Ethiopia. On the contrary, the Issa appeared more appealing force to counter balance and checkmate the Afar (Wonbede, 2009). The Ethiopia-Eritrea army joint military operation against the FREUD that rescued the Issa dominated government of Djibouti in 1992 from Afar imminent victory (Yayo, 2006) can be a naked attestation of their disfavor of the Afar. Among the Afar, this event is believed to have proved EPRDF’s policy (on other matters does favor the Afar interests but) on Issa-Afar violent conflict is the continued continuity of bygone regimes. As a result, despite their patriotic self image, EPRDF’s orientation caused very melancholic realization that whosoever comes to Ethiopian power center do not wish to see strong and united Afar. This collective anguish is often expressed in referring the Afar as the African Kurd or Palestine to connote the dismemberment of Afar homeland under three political constellations and the Issa invasion of their land respectively (Mu’uz, 2010).

The paradox of territoriality

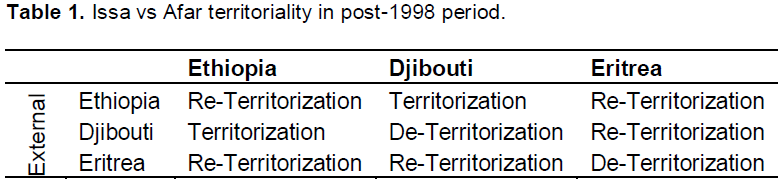

The grotesque Afar status in relation to Afar Horn governments has far reaching implication on the idea of territorial of the Afar, the Issa and respective govern-ments summarized in Table 1.

To the government of Eritrea, weak Afar in Ethiopia and Djibouti was in line with its policy of molding one and unified Eritrean identity without divisive kinship ties and ethno-social allegiance across its borders. It precisely fits into the service of the deterritorialization and homogenization policy the regime in Asmara aggressively pursued in the Red Sea Afar homeland (Bruce, 1998; Dinucci and Zeremariam, 2003). Inversely, it is hand in glove with its reterritorialization external policy with all its neighbors. The Issa dominated government in Djibouti has been consistent in internal deterritorialization that enabled to make Issa dominated state in thirty years and external territorialization to avoid encroachment from its big neighboring states (Schrader, 1993). The paradox is sharp with FDRE government that disavowed internal deterritorialization and territorialization in favor of principled constitutional reterritorialization (Tobias and Mulugeta, 2008) but enforces its emasculated version leaving wide space in favor of for power politicking that set the Afar on the debt side of the balance sheet. With no further ado, the Issa are better off than their rival kin. In all Afar-Horn states, the territorial policies are contrary to the universal Afar idea of territoriality and particular aspirations in their respective states. More so does the Afar in Ethiopia trapped in the incessant violent clash with the Issa and tormented by the memory of victimhood of the past than any of their kin in the Afar Horn.

Borders, wars and Zombie of mutual insurgency

The overall circumstance of Issa-Afar violence and especially the precarious position of the Afar were further complicated by the outbreak of Eritrea-Ethiopia Border conflict and Ethiopia’s subsequent dependence on Djibouti for access to the sea. The war was big blow to the already weak power coefficient of the Afar in Ethiopia. The Issa seemed to have realized the case that during the immediate outbreak of the war they launched massive penetrative campaign into Afar domicile in and around Buremodaytu Gelaelo and Afambo-Aysaita directions. The Afar, with aware of their precarious circumstances in a proactive defiance, put to defense fighters the legendary Ouggugumo Afar revolutionary nationalist movement, a mystified and cross generational self generating rhizome entity that geometrically multi-plies with its destruction, causing perhaps for the first time after fifty years heavy damage on the Issa. Since then to date the Ouggugumo is kept as shadow organization for the worst hour. Also, the Ouggugumo injected fresh blood (to the Issa of new crocodile breed) and via regular military training and war formation into the psychologically and morally devastated mass by all-time-all Issa invisibility (Mahmmud, 2009). To the Issa it is one of the bitter recent memories of victimhood as much as self restoration to the Afar (Robba, 2008).

The Federal Government of Ethiopia at this juncture was desperate to appeal to the Afar declared self ascription of patriotic zeal to show the at most restraint for their country’s sake; at the same time it approached the Issa with carefully crafted benevolence of a benefactor and reiterating the damages done to the Afar and the extreme restraint government did commit itself for the sake of future lasting solution. To the dismay of government expectations, neither the Issa nor the Afar showed restraint; instead fresh cycle of violence, hit and run robbery and killing targeting governmental and civilian committers began. The outbreak of anarchy at the height of the Eritrea-Ethiopia war made the Federal Affairs Minister and the commander of the National Defense Force division in the region to desperately resort to threatening to use of force least both groups fail to respond to the call of Mother land in its darkest hour. In response Issa and Afar elders worked hard to convince their respective people to cessation of hostility appealing to the sacrifices Issa-Afar men in uniform are paying for the common cause of defending the Mother land for no avail (ASJAB, 1999).

Instead both groups tried to manipulate the circum-stance to their myopic gains, while Afar-Issa youths continue paying dearly sacrifices at battle fronts. Federal Rapid and defense force detachments were stationed across the Hot Spots Awash to Gewane. Only the use of punitive measures by these forces tentatively succeeded in de-escalating violent incidents (Mu’uz, February-September, 2010/11; Kassa, 2010). At the elite level, Issa and Afar politicians compete over winning the favor of federal government as historical continuity of inter-group behavior during similar circumstances in the past; inter-subjective memories of acceptable and expedient behavior during national crisis seems animated by the war in acting paradoxically frustrating manner. At the center of which is the Arbegna vs. Banda divide that began during the Italian occupation and continued afterwards. In addition to the impact of remembering, perhaps two crucial considerations at the elite level explain Issa-Afar behavior.

The dynamics of developments in the battle front, in particular the Bure-Eastern front, had made the Afar region and Djibouti Republic of irreplaceable geostrategic and military significance providing the Afar and the Issa political tramp card to gamble with. Following the logic of war government worked hard to win the active support of both (ASJAB, 2007; ASJAB-S, 2007). However, the Issa and the Afar used different grammars in deciphering the logic of war to their subjective gains: worked with the anticipation of rendering government to take categorical position. They kept harping on binary strings while government promising lasting solution after ending the war kept singing ‘it takes two to tango’ (Ibid).

For the Afar the war was testing case of the double paradox the Afar are in; on the one hand Ethiopia’s dependence on Issa dominated Djibouti as the only access to fetch war supplies was to boost Issa influence in the power equation; on the other hand, the united (including dissident armed groups) Afar commitment demonstrated in defending country in the decisive Bure front besides (Abriha, 2008) Afar military strategic significance was ample opportunity that need to be carefully utilized in out maneuvering Issa influence. The patriotic activism of Afar and non Afar residents of the region were showing in backing up the war, especially the care and support provided for the wounded in the make major shift hospital set up in Semera (now seat of Afar regional government) was considered vital public diplomacy meant to influence long term civil and military officials (Indris, 2009; Adem, 2009). Similarly, the Issa, in addition to the Djibouti factor, worked to manipulate the counter intelli-gence offensive role of Red Sea Afar across the border and the strong kinship factor with the Ethiopia Afar as providing hub for insurgency. Furthermore, the presence of certain Ouggugumo splinters opposing both the state of Eritrea and Ethiopia during the war used to be invoked linking it with outbreak of violent incidents (IAJC, 1999).

Therefore, the historical embeddedness of Issa-Afar violence in national and regional developments was once again activated during the war; Issa-Afar competing maneuvering and counter-maneuvering efforts together with the tight conditions of war period made government to make unrealizable promises of lasting peace that did nothing more than postponing the ever more bourgeoning demands. After the war, government attention diverted to the post-war national and party politics that resulted in the spilt in TPLF power bock that the Issa-Afar question was not attended until the rise of cycle of violence. The TPLF-split in 2001 ousted influential old guards and brought new faces into the rank and file of party and government that brought power re-configuration at the political core of EPRDF-TPLF and minor reshuffling in the regions(Ibid). The delayed government response to the promises caused grievances among the population and elite groups resorting to spontaneous violent behavior and fall back to life in Gerbbo-Insurgency respectively (ALF, 2011). In effect, the post-war developments at the center and regions out dated Issa-Afar schemas design-ed during the war made regional elites unable to get the attention of government and to answer the demand of their nor contain violence. Thus, circumstance required both groups to draw the attention of the new Modus Vivendi and to devise new political modus operande. The fresh spiral of violence, though not fully, can be characterized to the need to beckon federal government attention and to the silent consensus on the effectiveness of no strategy other than causing insecurity. Targeting civilian and military commuters, closing the lifeline to Djibouti and the deliberate involvement of insurgents and members of the law enforcement and security organs of both regions, after which federal government responded immediately, supports the utility the fresh violence was employed in this particular context (IAJC-A, 2001). However, it is misleading to assume that the Issa-Afar carnage of this period at the grassroots was totally for the operative utility of elite politics of seeking government attention. Rather, as it is discussed in detail in the next section, Issa-Violence during this period was used for instrumental and operative utility of tangible and intangible values as well as for its symbolism. Often misjudged as nonsense (by external) but seldom analyzed unprecedented and demonical violent acts were witnessed causing ‘embarrassment’ even to the people involved in and directly affected by the violence.[1] To make sense of the ‘senseless’ violence of the period examining the emergence and hardening of four issues is crucial.

First, Issa-Afar historical skepticism of any Ethiopian government that be which began to decline with EPRDF rhetoric and practice of democracy, empowerment and self rule, and war time promises turned in to radical mistrust, despair and nihilistic violence. The catch phrase among the people was ‘governments do desire us in violence, even EPRDF; trust not the Issa /Afar, even more the government!’ Fearful, angry and oblivious about what to do between them, and disdainful of government intentions they got obsessed with lamenting what they surely know and trust, their past and the collective archival memory of violence. Thus, indulged in relentless re-membering and re-presentation of memory of violence in search of meaning to their melancholic situation and to their senseless violence so that it fits communal narratives of long term aspirations and immediate security needs; that in turn brought the discursive utility of violence as symbolic representation of the being (the nowhere) and becoming (the Arrivant) of their identity. Second, the no peace no war state with Eritrea and Ethiopia’s dependence on Djibouti introduced contexts that promote violent attitude and behavior. The tense situation and resumption of mutual-insurgence between Eritrea and Ethiopia in arming and weaponizing each other’s dissidents brought insurgency in to the center of whirlwind of Issa-Afar violence. The direct participation in violent acts and arms trafficking of insurgents, in addition to being used for mutual-incriminatory politicking, caused the militarization of society. The growth of arms trafficking and contraband trade mainly among the Issa and the emergence of powerful contraband class which cannot benefit unless from the dividends of Issa-Afar violence otherwise intensified militarization and widened social sphere of violence. Government reluctance to take lasting measures against open contraband centers owing to the Issa-Djibouti connection and against Afar insurgency due to the Eritrea factor on the one hand and the reservation of regional authorities to combat insurgency and banditry on the other hardened Issa-Afar-Government mistrustful attitude and violent behavior. Third, the partisan involvement of regional authorities in active violence resulted in the consistent failure of federal government brokered peacekeeping, breaching of peacemaking efforts and the disappearance of culpability that in turn promoted crisis of legitimacy and of non-ephemeral structures of representation. Consequently, asserted violent behavior as accepted and expedient within no approved and formalized opportunity costs sanctioned in return. Fourth, with the ever rising unmitigated violent incidents, death tolls and scene of mountain of wreckages, the memory of trauma and its neuropsychological insatiable urge to prevail over the existential source of fear, in the tragic prototype of the absurd, exponentially intensified fear and the nihilistic urge to prevail over it. Hence, the inconsequential affirmation of violent attitude and behavior feeding on the structures of remembering and representation of memory of violence grew unattended establishing direct acts of violence as expected and approved standard of being in a group. Opinion survey results carried out among the Afar and the Issa at different periods during 2009 and 2010 confirmed this conclusion; irrespective of sex, age, income, education and direct experience in violence they approve violent action.

During the post-war period only, from the 2000 up to the Eritrea-Djibouti border skirmish in 2010 around Ras Dumera, more than two dozens of conferences, and countless consultation workshops and joint meetings and dozens of accords have been made. None of them succeeded in either settling issues or deescalate frequency of violence nor the progressive advance into and eviction of the Afar, and subsequent laying of claim for recognition as Issa self governing unit; the case in point is the Issa claim over the Hot spots at Adaytu, Gedamaytu and Qunduffo. In response to the unabated Issa advance, the Afar did not fail attempting to avail themselves of domestic and sub-regional unfavorable developments to Issa the like period of drought, famine and even the RasDumera incident with the anticipation of recapturing lost territories. Unfortunately, except for few instances of causing heavy damages on the Issa and forestalling further advances, the Afar has never achieved to reclaim territories lost to the Issa.

By and large, the federal government chose to once again postpone lasting solution associating lasting Issa-Afar peace with the imperative of ensuring development to both communities; and it preferred to manage and control direct violent incidents using federal police and national defense detachments which do not provide more than fire brigade function; yet, these forces were not spared of partisan involvement accusation and direct violent assaults from both sides (ASJAB-C, 2002-2010). In the end all joint peace constellations at all levels gradually transpired by their own accord and to both regions the case was deactivated from annual plans of action for unlimited time in the future, up until federal government wills to end the drama. In the mean time, the unabated continuity of violence had been transforming itself in to approved, expected and regular behavior of society aesthetisized in perpetration of unprecedented banal violent acts; hence, Issa-Afar Dramaturgy of violence.

Issa-Afar dramaturgy of violence

The dramaturgical metaphor, pioneered by Goffman, in the late 1950s, is commonly applied to analyze the beha-vior of people in presenting themselves through unique acts (rituals or performances hence called ‘performative’) to an audience other for non-consequential purposes. Basic to the metaphor are violence as performance, the presence of an audience and non-instrumentality of the violent act (Barkun, 2005). It appears apt to analyze recent Issa-Afar violence, for the dramatic nature, the deliberate addressing of the other as witness audience and the absence of tangible and intangible utility of violent. These conceptual considerations have allowed academics to extend the dramaturgical metaphor to analyze acts of religious terrorism including the September 11/2001 attack: apparently poetic and non-instrumental (Juergensmeyer, 2009). Its applicability to Issa-Afar violence is on double counts; its performative nature and novelty.

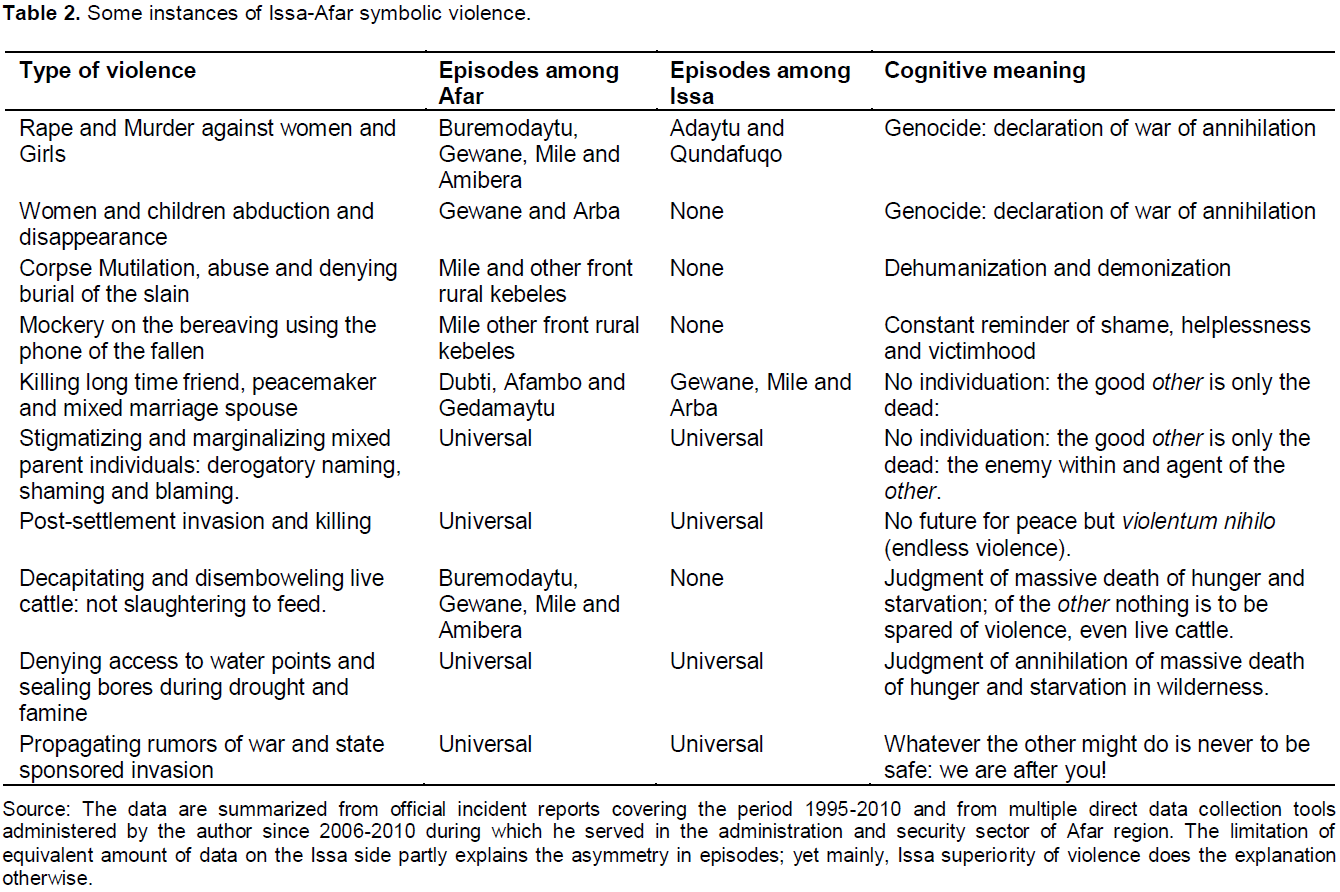

Left to its accord, the nature of Issa-Afar violence discussed earlier mutated in to strange acts of sheer brutality inviting men and women, children and elderly, including police and security officers that high authorities of the Afar region including the President and Security head had to use the disguise of non-Afar plates to cross Issa occupied territories in their de tour to Addia Ababa direction. Ordinary Afar folk do not dare to set out of public transport or government vehicles in these territories or speak in Afar language in commuting for fear of being killed on sight. Similarly, the author has witnessed, the Issa face the same fate in traveling in Afar towns, for instance in commuting from Djibouti. Moreover, series of inconsequential and dramatic violent acts flamboyantly staged for the other as, audience of its own victimization as though a spectacular play on the arena, became most frequent experience. The fact that the inconsequential new violent acts militate the purview of subjective cognitive structure of remembered violence and had neither experiential nor operative utility made violence as social sacred drama of symbolic utility. Though accounting experiences of victimization and trauma is not in the scope of this study, stories of victimization and trauma from the new face of violence among the Afar and the Issa got pervasive pedigree. With the view to cast the bird’s eye’s view of the new violent drama and dramatic violence, few most frequented types of the recent violence are summarized in Table 2.

The examples of violent episodes summarized above have no instrumental utility except the banal drive to cause as much trauma as possible: violence for itself. The effort to give novelty to cruelty is ostensible from the acts and the knowledge of corresponding Connative meaning which are unbearable in any circumstances that be; hence, attestation of the dramaturgical turn of Issa-Afar violence. Tragically, state and non-state actors never got a glimpse of the new violent dynamics.

As is the case with every new comer minister in dealing with the Issa-Afar issue, up on coming to office the new Minster of Federal Affairs, joint conference chaired by the ex-Minster Abay Tsehaye was held in Awash Sebat on June 2011. The proposal provided by the Minister was recommendation for mutual and legal recognition of the Issa occupied territories to be part of the Shinile zone self governing units under Somali region in return for making lasting peace. This had been the last thing the Afar would do; and they vehemently condemned the idea and the walk out of the conference in rage. For months to come anger against federal government was expressed in violent attacks against federal government truck drivers and a Trans-Ethiopia track (owned by TPLF-affiliated endowment enterprise) was attacked with shower of bullets in Mile. However, these single incidents were mere vents to release the immense frustration caused by the proposal. The major consequence was the popular anger against the regional leadership accusing them for treason against and bartering the Afar cause for long term political carrier: the president Ismael Ali Sero was the most demonized. A couple of months later, confusions cleared to see their leaders were not part of the plot; but the frustration caused by the conference was directed against the Issa in subsequent outbreak of violent incidents that engendered human causality on both sides of the divide (Mu'uz, 2011).

Since then up to the very recent peace agreement signed and televised on December 14, 2014 (EBC, 2014), no attention had been given to the powerful role of the communal memory of violence, the syntax and morphology of remembering and representation of violent episodes perpetuating the cycle of violence. With hind sight to the agonizing path the Afar and the Issa has gone through, the imprints every violent experience left on communal psychic and the grotesque turnedness associated with it, however noble and well intentioned a peace accord may be lasting peace is farfetched without dealing the unattended dimension of memory of violence.

In sum, therefore, for now what can certainly be said is that violence in all its forms and utility has engulfed society to the level of banal complexity. In effect, irrespective of consequences to kill or die trying in Issa-Afar violent incident has become unquestionable act to be performed-Performative; if left unabated is to become universal common sense of communal ethics-New Connative, and the way of dealing with insecurity-New Operative, worse if banal acts get instrumental utilities to justify themselves with; for now, Issa-Afar violence has partly become the symbolic act of and for no tangible or intangible utility imaginable-Dramaturgy, no one rejects without running the risk of being the other.

[1]The author has witnessed participants of endless peace conferences, negotiation works and meetings, after hours of endless verbal belligerency and up on sudden cognition of the banality of the cycle of violence, expressing their embarrassment as ‘why do we live like this , . . . is it divine curse for Muslim kin to keep killing each other like wild beast? Isn’t the land wide enough to keep us in peace side by side . . . ?’ Tragic enough, the rare peace accords made in this spirit has never lasted weeks before transpiring by fresh wave of violence, however. This could be one indication of the need for further examination of the powerful impact of communal memory of violence, the process of remembering and the narrative structure of representing unlived experience in seamless alliance with the nowhere life.

CONCLUSION

The nature and utility of Issa-Afar violence has entered the realm of inconsequentiality; it is no longer about hitherto upheld tangible and intangible utilities per se has gained performative features; the remembering and representation of memories of violence gave the emergence of dramaturgical violence, inversely, the latter is setting the context for the reconstruction of frameworks of remembering and narrative structures of re-presentation of violence that fits the degree of trauma and victimization engendered by dramaturgical violence. This is evident from the obsessive nihilistic urge for violence on both sides and the impossibility of closure to lived and remembered traumatic experiences of victimization in the immediate future. While the invisible cultural and structural violence of memory and history of violence is the ever festering wound of Nietzsche keep on causing visible irreparable damages, the invisible impacts of the most visible dramaturgical violence is misjudged for its visible impacts. Thus, given the current circumstances of disorientation in peace keeping and peacemaking, the destructive entropy of the visible and invisible (greater than 2R +D) violence is harbinger of bigger evils in the time to come.

Therefore, it is commendable to give sufficient attention to efforts of creating contexts of closure to lived and remembered collective trauma and victimization, healing to the ever festering wound, forgiveness and mercy to reign as much as the immediate need for reducing direct violence. Also, peacekeeping to reduce direct violence-not mere but frequently expressed in dramaturgical fashion- should not apply conventional strategies tailored for the ordinary; rather, it need to be innovative to integrate the need for Reconstruction, Reconciliation and Resolution (3Rs) in one package. Borrowing Galtung’s metaphor, the task of addressing the expression and impact of invisible and the visible violence, immediate basic need of reducing justice (Reconstruction), middle-term Resolution of incompatibilities and Long-term Reconciliation and overall Reconstruction of society should not be comprehended and done in diachronic frame; should be synchronic; all imperatives got to be synchronized at once with clear image of the bigger picture and envisioning of the future horizon.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

| AIKW GOIK (1956). Top Urgent AICIRs of AIKW-Afdem. Addis Ababa: MoI Archives. | ||||

| Abriha M (2008). 'Badmen ende Mikinyat'. Addis Ababa: Mega Publishing. | ||||

| Adem A (2009). Issa-Conflict During the Eritrea-Ethiopia Border War. (Mu, & u. Gidey, Interviewers). | ||||

| Ahmed A (2010). The decline of the Awusa Sultanate. (M. Gidey, Interviewer). | ||||

| AIAG (30/1/53). Issa Situation Report: Regarding the fund Raising among the Issa forthe Somalia Government. Dire Dawa: np: AIAGO Records. . | ||||

| AIAGO (23/11/52). Situation Report of the Political Rumors discussed around Issa Elders to HGGO. Harrar: np: HGGO Records, Archival No. 3731. | ||||

| AIAGO (8/11/52). 'Crisis Report of the nomadic Issa has caused on us'. Harrar: np: HGGO 1st records. | ||||

| AIAO (2/12/52). Top Urgent and Classified: dal and Issa Awuraja Office (AIAO) AICIR to HGGO. Erer: np: AIAO Records, Ref/No. 2/7065/. | ||||

| AIGO (20/02/46-1956). AICIRs by Adal-Issa Governorate Office (AIGO) to MoI. Addis Ababa: MoI, Archive No.11/94. | ||||

| AIGO (30/1/ 53). Unique Situation Report: Regarding the fund Raising among the Issa-Somali for Somalia. Dire Dawa: np: AIGO records. | ||||

| AIWG A (18/04/47). AICIR by AIWG on 18/04/47 ("the Issa attacked the Afar once again"). Harrar: np: HGGO 1st Records. | ||||

| AIWGO (5/7/39). AICIR: "Request for the Necessity of dispatching Armed Forces Back up")by AIWGO.to the Acting Governor of AIG. Asebe Teferi: np: AIGO Records, Ref. no. 563/17. | ||||

| AIWGOR (5/7/39). Top Urgent and Classified AICIR to PSSO Records. Addis Ababa: np: PSSO Records, archive no. 623/17. | ||||

| Alessandro D, Zeremariam F (2003). Understanding the Indigenous Knowledge and Information Systems of Pastoralists in Eritrea [Journal] // Communication for Development Case study 26, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome. | ||||

| ALF I (2011). February and March 15 February to 29 March). On the politics of Afar Insurgency. (M. Gidey, Interviewer). | ||||

| Anderson B (2006). Imagined Communities: Reflekction on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Revised Edition. London and New York: Verso. | ||||

| ASJAB (1999). Issa-Afar Peace Conference Report. Semera: np: ASJAB Archive. | ||||

| ASJAB (2007). Issa-Afar Joint Peace (IAJP) Conference Report. Semera: np: ASJAB archives. | ||||

| ASJAB (2007-2008). Issa-Afar Joint Peace (IAJP) Conference Reports . Semera: np: ASJAB archives. | ||||

| ASJAB-C (2002-2010). Violence incident Reports against members of the federal police detachment. Semera: np: AJSAB IACIR archives. | ||||

| ASJAB-S (2007). Issa-Afar Joint Peace workshop Report. held at Gewane: np: ASJAB archives. | ||||

| Bruce JW (1998). Country profile of land Tenure. Africa, Land Tenure Center, Institute for Research and education on Social structure rural institutions, resource use and development, University of Wisconsin, Madison, 160-169. | ||||

| CCTTD (12/1/960). Top Secret Military Operation Plan to enforce law and order among rebellious Issa Clans by B/General Abebe Gemeda, Chief Governor of Territories Under State of Emergency and Commander in Chief of the 3rd Infantry Division (CCTTD). Asebe Teferi: np. | ||||

| Dire Dawa AA (26/01/46). Top urgent and Confidential, Adal Issa Conflict Incident Report (AICIR). Dire Dawa: DAIG. | ||||

| Duany W (1993). Neither Palaces nor Prisons: The Constitution of Order among the Nuer. PhD Indiana: Indiana University Department of Political Science and the School of Public and Environmental Affairs Indiana UniversityBloomington, Indiana, USA. | ||||

| EBC (2014). EBC News: Issa-Afar Peace Accord. Addis Ababa. | ||||

| Ethiopian Review (1992). Even our camels know the flag of Ethiopia. Ethiopian Rev. 4(3):11-13. | ||||

| ESDM (1992). Ethiopian Somali Democratic Movement (ESDM), Economic and Social Program. Semera: np: ASJAB archives. | ||||

| ETV (2008). Documentary on History of the Harella [Motion Picture]. | ||||

| FGD A (2010). Issa-Afar Conflct dynamics. (M. Gidey, Interviewer) | ||||

| FGD I (2010, February 8, Harewa). Issa-Afar Conflict dynamics. (M. Gidey, Interviewer). | ||||

| Galtung J (2003). After Violence: Reconstruction, Reconciliation and Resolution: Coping with Visible and Invisible effects of war and Violence. NP: NP. | ||||

| Gebrewold B (2009). Anatomy of Violence Understanding the Systems of Conflict and Violence in Africa. Brussules Signate. | ||||

| Gemaludin SI (2007). Ancient History of the Afar/Denakil:Almanac. Addis Ababa: Tirat Publishers. | ||||

| Government B (12/5/48). Confidential: British Government Letter of Protest to Ministry of Foreign Affair (MoFA). Addis Ababa: np: MoFA Periodicals and promotion Records. . GTW (29/2/53). Classified: Situation Report From Governor of Teferi-Ber wereda (GTW) to Ogaden Awuraja governorate office (OAGGO). Jijiga: np: OAGGO 1st Records, Archive No. 1/205/ 967/1. | ||||

| HAGOR (1/9/47). Minuet of the structure and organization of Offices within AIWG. Harrar: np: HGGO 1st records . | ||||

| Hamedu FT (2009). The Harrela Cataclysm. (M. Gidey, Interviewer) | ||||

| HF SA (2008). Issa-Afar Conflict dynamics. (M. Gidey, Interviewer) | ||||

| HGGO VO (17/10/49). Confidential AICIR. Harrar: HGGO 1st Records Archive No. 1002. | ||||

| HGGO (1935/6). AICIRs of 1935-36. Harrar: np: HGGO Records of 1935-36. | ||||

| HGGO (1945-74). AICIRs. Harrar: HGGO Records: 1945-74. HGGO (9/1/44). Petition of Clan chiefs and elders of the Adal to the director of HGGO. Harrar: np: HGGO Archive no. 61/400/39. . | ||||

| HGGO HG (26/01/46). AICIR, Archive No. 563/7. Harrar: HGGO. | ||||

| Hirsi A (2009). Issa perception of the Afar. (M. Gidey, Interviewer). | ||||

| IAJC (1999). Issa-Afar Joint Peace Conference Report. Adaytu: IAJC. | ||||

| IAJC-A (2001). The Adaytu Conference Report. Semera: np: ASJAB archives. | ||||

| Indris Y (2009). Issa-Afar Conflict during Eritrea-Ethiopia Border Wa. (M. Gidey, Interviewer) | ||||

| JAGO (29/2/53). Classified Report of the fund raising underway by the Issa from Jijiga Awuraja Governorate Office (JAGO). Harrar: np: HGGO 1st Records, Archive No. 649. | ||||

| John (ed.) C (2001). 'Of Remembering'. Zurik: Z books. | ||||

| Juergensmeyer M (2009). Terror in the Mind of God: The Global rise of Religious Violence. Berkley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press. | ||||

| Kassa MK (2010). Issa-Afar Conflict during Eritrea-Ethiopia Border war. (M. Gidey, Interviewer) | ||||

| Leaderach JP (2003). The Little Hand Book of Conflict Transformation. Syracus : Good Books Publisher. | ||||

| Yasin YM (2008). Political History of Afar in Ethiopia and Eritrea. The African Spectum GIGA: Institute of African Affairs, Humburg. 42(1):39-65. | ||||

| Mohammed A (2010). Afar view of Issa Violenc e . (M. Gidey, Interviewer) | ||||

| Mohammed A (2010). The decline of the Awusa Sultanate. (M. Gidey, Interviewer). | ||||

| Mahmmud S (2009). On the recent Issa-Afar conflict dynamics. (M. Gidey, Interviewer). | ||||

|

Markakis J (2003). Anatomy of a Conflict: Afar and Issa in Ethiopia [Journal] // The Horn of Conflict. Review of African Political Economy. 30(97). Crossref |

||||

| Mayru A (2010). The decline of the Awusa Sultanate [Interview]. - November 5, Aba'ala,. | ||||

| Md WA (2008). Issa-Afar Cofnflict during the Dergue period . (A. Abdu, Interviewer). | ||||

| MoFA (1995-2010). Issa-Afar Conflict. Semera: np: ASJAB records. | ||||

| Mohammed A (2009). Afar perception of the Issa. (M. Gidey, Interviewer). | ||||

| MoI Department of public Safety and Security (MoI-PSS). (15/08/1960). MoI Communique to Ft. Aemirosilasie Abebe vice Viceroy of HGG, Harrar: Vice VGGG archives, Ref. No.Ts/166FaPo/52/1. | ||||

| MoP (1946). Adal-Issa Boundary Demarcation Decision from Ministry of Pen (MoP) to HGGO. Addis Ababa: MoP Archive No. 2647/1946. | ||||

| Mu'uz G (2010). 'The Afar-Issa Conflict in post-1991 Period: transformative Exploration' Theses for the partial fulfillment of MA in PSS, AAU, UPEACE-Africa. [Book]. - Addis Ababa-AAU: np. | ||||

| Mu'uz G (2011). Field note of violent incidence in 2011 at Mile Wereda. Dessie: np: personal collection. | ||||

| Mu'uz G (2010/11). Author's Prison Diary. Dessie: np: personal archive. | ||||

| Musa S (2010). The decline of the Awusa Sultanate [Interview]. - Novemeber 2, Kelewan. | ||||

| Mu'uz G (2010). Author's Prison Diary [Report]. -Dessie: np: personal archive, February-September. | ||||

| Mu'uz G (2011). Field note of violent incidence in 2011 at Mile Wereda [Report]. - Dessie: np: personal Collection. | ||||

| Mu'uz G. Afar Diary 2005-2010 [Art]. - Semera: Personal. | ||||

| PMGSE (1987). Top Urgent and Classified Report of Afar-Issa Conflict Resolution Proposal by Chairman of the PMGSE, Mengistu H/Mariyam. Addis Ababa: np: Ref. No. MG1/L/46/012/7. | ||||

| PSSO (25/11/52). Classified Military Operation to settle the 1st Battalion of armed forces at Ayisha to control rebellious Issa clans. Addis Ababa: np: MoI-PSSO, Central Command Office Records. . | ||||

| Robba G (2008, September 10, at Haro Kersa Kebelle, Fentale Wereda). The role of the Ouggugumo in Afar-Karayu conflict. (M. G. Shekur, Interviewer). | ||||

| Roble H (2009). The decline of the Awusa Sultanate. (M. Gidey, Interviewer). | ||||

| Schrader JP (1993). ethnic politics in Djibouti: from the eye of the Hurricane to 'boiling cauldron'. Journal of the Royal African Society, 93(307) (African Affairs), 203-221. | ||||

| Shukri, A. (2009, June 8). The history of the Harella. (M. Gidey, Interviewer). | ||||

| Tahiro M (2008). Role of Customary Conflict Resolutions. (S. Mahmud, Interviewer). | ||||

| Tekole B (2008). on the Issa Afar Violence. (M. Gidey, Interviewer). | ||||

| Tobias H, Mulugeta A (2008). Pastoral Conflicts and State building in the Ethiopian lowlands [Journal] // Afrika Spectrum GIGA. 43(1):19-37. | ||||

| VHGG VO (17/10/49). Confidential: Adal-Issa Conflict Incident Report(AICIR). Harrar: HGGO 1st Records Archive No. 1002. | ||||

| Wonbede I (2009). the Afar-Horn during the transitional period. (M. Gidey, Interviewer). | ||||

| Wsphycogrod E (2001). The ethics of Remembering. Zurik: Z books. | ||||

| Yayo A (2010). The decline of Awusa Sultanate . (Mu, & u. Gidey, Interviewers). | ||||

| Yayo Y (2006). Role of Customary Conflict Transformation Mechanisms. (M. Gidey, Interviewer). | ||||

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0