ABSTRACT

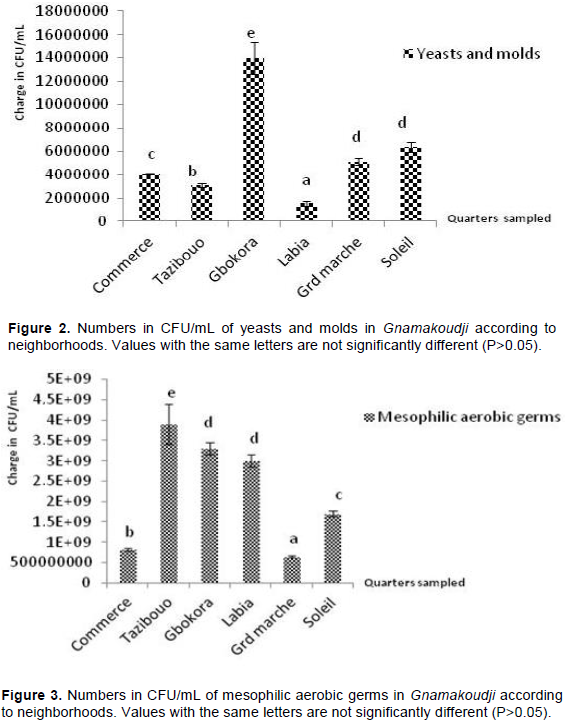

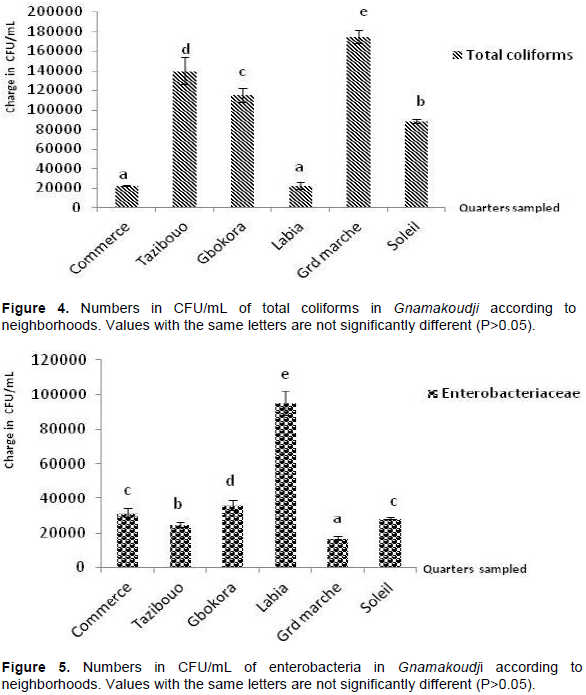

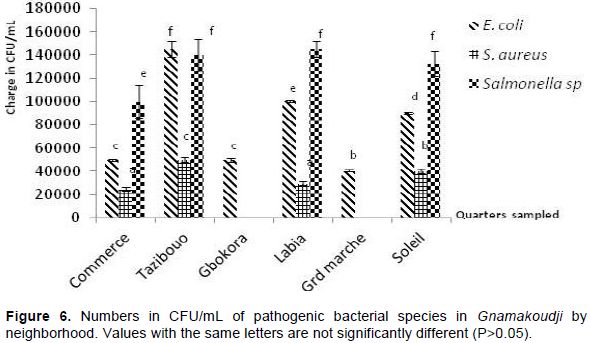

Street food has become unavoidable in the current scheme of restoration in urban Africa. This study aimed to study the microbiological contamination of a refreshing artisanal drink, Gnamakoudji, made from Zingiber officinale sold in the city of Daloa (Côte d’Ivoire). Physicochemical tests showed that Gnamakoudji is an acidic drink (pH ≈ 3.83) and very sweet (0.2 gmL-1). Microbiological analyses revealed a high level of contamination. For mesophilic aerobic germs, the CFU/mL load ranged from 6.5×109 to 3.9×1010. The CFU/mL load for yeasts and molds ranged from 1.5×106 to 1.4×107. Total coliforms and enterobacteria ranged between 2.2× 104 to 1.7×105 CFU/mL for the first and 1.7× 104 to 9.5x 104 CFU/mL for the second. Worse, pathogenic bacterial species have been found in the Gnamakoudji of all neighborhoods. Gbokora and Grand-marche Gnamakoudji were contaminated with E. coli alone with 5x105 and 4x105 CFU/mL, respectively. That of the other neighborhoods contained both E. coli, S. aureus and Salmonella sp. The charges in E. coli and S. aureus oscillated between 4×104 and 1.4×105 for the first and 2.5×104 to 5×104 CFU/mL for the second. Salmonella sp was found in samples from the other four quarters (Commerce, Tazibouo, Labia and Soleil) with loads that ranged from 105 to 1.4×105 CFU/mL. These colony counts were unequally distributed and far exceeded the microbiological standards for juices and fruit drinks. The empirical manufacture of Gnamakoudji and the difficult sales conditions would increase the risk of contamination. The street Gnamakoudji is unfit for human consumption. Strategies to ensure the availability of a healthy Gnamakoudji must be put in place with government authorities, the private sector and consumers. This scientific data could help to develop codes of practice for the safety of Gnamakoudji in order to avoid diseases transmitted by street foods.

Key words: Microbial contamination, gnamakoudji, street food, Daloa, Côte d’Ivoire.

In recent decades, street food has become an essential source of food in the major cities of developing countries. These foods are defined as ready-to-eat foods and beverages prepared and/or sold by street vendors or fixed vendors (FAO, 2014a). Rapid urbanization and the multiple constraints associated with it such as the distance between workplaces and home, poverty, the development of women's activity, the breakdown of family solidarity, and the emergence of new food styles would explain the expansion of this activity in Africa (Compaoré et al., 2008). The city of Daloa with 5,305 km2 of area is the third most populous city of Côte d'Ivoire after Abidjan and Bouake. Its population increased from 163,537 in 1998 to a population of 245,350 at the last general census in 2014 (RGPH, 2014; Zah, 2015). Today, the population is estimated at more than 288,000 inhabitants.

With rampant urbanization, Daloa is also confronted with profound changes in lifestyles, work activities, family and social relations, which crystallize the problem of food security. Thus, this constantly growing population with the many administrative changes (commune, sub-prefecture, department and region, university town), has a clearly growing need for food, and street food has become a major source of food. Local craft drinks made from local fruits or vegetables are part of street foods. Of these, the drink Gnamakoudji (based on ginger (Zingiber officinale)) is very well known. This non-alcoholic, hot-tasting traditional drink is appreciated and abundantly well-known in many countries of the sub-region, as is the case in Côte d'Ivoire (Nandkangre et al., 2015; Mpondo et al., 2017). This drink, extracted from the rhizome, is a refreshing drink during weddings or baptisms. It is consumed alone as in family (Nandkangre et al., 2015). In Daloa, it is sold along roadsides, in markets and areas with high population densities such as schools and bus stations. Because of its cost accessible on all budgets, this refreshing drink is an important part of people's eating habits. However, during processing, this drink can be contaminated by various microorganisms including pathogens.

In addition, street foods are known to be frequently associated with diseases and several microbiological analyses have revealed the presence of many pathogenic microorganisms with loads exceeding the standards (Barro et al., 2007; Chenouf et al., 2014; Mbadu et al., 2016). In addition, several outbreaks of disease have been attributed to beverages in various parts of the world and some infections have been reported in populations consuming these street foods (WHO, 2010; Mihajlovic et al., 2013; Kouassi et al., 2018). If the diet of this drink has proven positive aspects, the microbiological quality remains doubtful (Kouassi et al., 2012; Bayoï et al., 2014; Mbadu et al., 2016). Except, to our knowledge, no study on the quality of this soft drink sold in the city of Daloa has yet been the subject of scientific study. It is in this context that this study falls under the theme: Microbial contamination of a non-alcoholic soft drink sold in the streets of Daloa: the case of Gnamakoudji (Z. officinale). The overall objective of this study is to evaluate the microbial contamination of this non-alcoholic refreshing drink sold in the streets of Daloa. It also aims to diagnose the manufacturing process, looking for physicochemical parameters of this refreshing drink sold in the streets of Daloa. The information obtained can be used to educate producers and consumers about the quality and safety of this drink produced in the city of Daloa, or even throughout the country.

The study material consists of the non-alcoholic drink called Gnamakoudji sold in the streets of Daloa. This drink is made from ginger (Z. officinale).

Investigation for the diagnosis of the manufacturing process of Gnamakoudji

Information on Gnamakoudji drink manufacturing processes was collected from 10 producers in the city of Daloa. The information concerned the different stages of the manufacture of the Gnamakoudji drink.

Sampling

Samples of Gnamakoudji were harvested in six (6) main districts of Daloa City (Commerce, Tazibouo, Gbokora, Labia, Grand marche and Soleil). In each neighborhood, three samples each consisting of three bottles (250 to 330 mL) were collected at the same point of sale. The various points of sale were either on the roadsides, in the markets or in areas with high population densities such as schools and bus stations. In these different outlets, drinks are exposed to room temperature. Samples once taken are stored in a cooler with dry ice and transported to the laboratory for analysis. These analyses were done at the Laboratory of Host-Microorganisms and Evolutions Interactions (LIHME) of University.Jean Lorougnon Guede.

Physicochemical characterization of Gnamakoudji

Determination of the pH

The determination of the pH is carried out using a pH-meter (PHS-38W). A quantity of 150 mL of the sample was used for this purpose. Three (3) measurements from one sample of 150 mL were performed.

Determination of Brix degree and amount of sugar in Gnamakoudji

The degree of Brix was measured using a portable refractometer (ATAGO N-1α) measuring up to 30 Brix. Three measurements were performed per sample. For the determination of the amount of sugar in the beverages, the volume of beverage contained in the bottle was spilled in a beaker and weighed. From Brix degrees and determined beverage masses, the amount of total sugars contained in a bottle of Gnamakoudji was calculated according to the formula described by Monrose (2009):

Quantity of sugar in the product (g) = (Brix degree of the product / 100) × Amount of product (g)

Microbiological characterization

Methods of analysis

Buffered Peptone Water (BPW) broth was used in the preparation of stock solutions as described in ISO 6887-4: 2011. Decimal dilutions were performed with Tryptone Sel broth as recommended in ISO 6887-1: 1999. Plate Count Agar (PCA) was used to count mesophilic aerobic flora at 30°C for 72 h as recommended in NF/ISO 4833: 2003. Enterobacteria count was performed at 37°C for 24 h on Violet Red Neutral Bile Glucose (VRBG) agar according to ISO 21528-2: 2004. Violet Neutral Bile Lactose (VRBL) agar was used for total coliform count at 30°C for 24 h as described in ISO 4832: 2006. For the search, isolation and enumeration of Salmonella, media Buffered Peptone Water (BPW), broth Rappaport of Vassiliadis Soya Broth and Hecktoen Enteric Agar were used as described in the reference standard NF/ISO 6579: 2002 Amd 1: 2007. Baird-Parker Agar with Telluride Egg Yolk and 0.2% Sulphamethazine served the identification of Staphylococcus aureus at 37°C for 48 h according to the French standard NF/ISO 6888: 2004. Rapid'E coli 2 agar served the isolation and enumeration of Escherichia coli at 44°C for 24 to 48 h as recommended in standard NF/ISO 16140: 2013. Yeasts and molds were counted with Sabouraud agar chloramphenicol 25°C for 5 days according to the NF/ISO 16212: 2011 standard. The different culture media used were prepared according to the manufacturers' instructions.

Preparation of the stock solution and decimal dilutions

Twenty-five milliliters (25 mL) of Gnamakoudji's sample was aseptically transferred to an Erlenmeyer flask containing 225 mL of sterile (BPW) medium to prepare the stock solution. After a 1 hour rest on the bench at room temperature, the stock solution was decimally diluted in sterile Tryptone Salt medium up to 10-6.

Inoculations and incubations

Research of mesophilic aerobic germs, yeasts and molds, total coliforms, enterobacteria and Escherichia coli

According to the prescriptions of the standards adopted, the pour plate method was applied. Thus, one milliliter (1 mL) of the diluted Gnamakoudji sample to be analyzed is aseptically transferred to a sterile Petri dish and mixed with 20 mL of the respective agar. After solidification, the dishes are inverted and incubated at temperatures as given in the respective standard. Three Petri dishes were inoculated per dilution. The characteristic colonies according to the different media are then counted taking into account the calculation standard (NF/ISO 7218: 2007).

Research of Staphylococcus aureus

The surface spreading method was used for the detection of S. aureus. It consisted of taking 0.1 ml of the stock solution or a dilution of the Gnamakoudji sample to be analyzed, using a sterile pipette, and transferring to a Petri dish containing the Baird Parker agar medium already poured and solidified. The dilution is spread on the agar using a spreader rake. These manipulations are all performed under aseptic conditions near the Bunsen burner flame. Petri dishes are then inverted and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Two plates of petri were seeded by dilution. Black colonies with a clear halo (action of lecithin) and an opaque zone (action of lipase) are counted (15-150 characteristic colonies) taking into account the dilution.

Highlighting Salmonella sp.

It is done in three stages. Pre-enrichment is performed by incubating the stock solution at 37°C for 24 h. The enrichment consisted of taking 0.1 mL of the stock solution (pre-enriched) and transferred to a tube containing 10 mL of Vassiliadis Rappaport previously prepared and sterilized. After homogenization, the tube is incubated at 42°C for 24 h. Finally the isolation was carried out from the enrichment medium incubated on a solid selective medium: Hecktoen agar. A drop is taken using a Pasteur pipette and then seeded by streaks on the surface of the Hecktoen agar. The dish is incubated at 37°C for 24 h, and sometimes even for 48 h, in the absence of characteristic colonies after the first incubation. On Hecktoen agar, the typical Salmonella colonies observed are green or blue with a black center.

Enumeration

The number of Colony Forming Units per milliliter of sample (CFU/mL) from the number of colonies obtained in the Petri dishes is carried out according to standard NF/ISO 7218: 2007

ΣCi: Sum of characteristic colonies counted on all retained Petri dishes;

N1: Number of Petri dishes retained at the first dilution;

N2: Number of Petri dishes retained at the second dilution;

d: Dilution rate corresponding to the first dilution;

V: Inoculated volume (mL);

N: Number of microorganisms (CFU/mL).

Standards for assessing the microbiological quality of Gnamakoudji

The microbiological quality assessment standards for Gnamakoudji are taken from the “Microbiological Criteria for Foodstuffs - Guidelines for Interpretation of 2015 of Luxembourg”.

Statistical analyses

The different parameters analyzed were then subjected to an analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the software Statistica, 99 Edition. For this purpose, a single-factor ANOVA and Duncan's multi-extended tests were used. ANOVA was used to test, on the one hand, the variability between the different samples. As for Duncan's test, he later made it possible to first locate the differences between the samples and then the differences between them. Statistical differences with P-values under 0.05 were considered significant.

Evaluation of the manufacturing process of Gnamakoudji

All the information collected from the manufacturers, unit processing operations are essentially the same, with the exception of the rhizome peeling stage which is not carried out by some manufacturers. These operations are carried out on the same production site except the grinding phase which is carried out in another site (market, or grinding machine site). The essential operations are illustrated by the Gnamakoudji manu-facturing diagram (Figure 1). However, no heat treatment is associated with the manufacture of this drink.

Physicochemical characteristics of Gnamakoudji

The physicochemical studies carried out on the various drinks made it possible to determine the Brix degree and the pH summarized in Table 1. Gnamakoudji is an acidic drink with an average pH of 3.81 ± 0.12. The Brix degree ranged between 16.93 and 19.73. The estimated Gnamakoudji sugar level from Brix degrees and drink masses is about 0.20 g/mL.

Microbiological characteristics of Gnamakoudji

The microbiological studies carried out allowed the counting of microorganisms, the main weathering flora or flora evoking a lack of hygiene (yeasts, molds, mesophilic aerobic germs, total coliforms and enterobacteria) and pathogenic species in Gnamakoudji. Drinks from all sampled neighborhoods were heavily contaminated by these different floras. In addition, all flora charges (CFU/mL) were all well above the expected microbiological quality standards (norm NF in 2073/2005/CE). The CFU/mL load for yeasts and molds ranged from 1.5×106 to 1.4×107, whereas the standard predicts 105 (Figure 2). The counts found in the Gnamakoudji neighborhood Soleil and Grand-marche were not statistically different (p> 0.05). For mesophilic aerobic germs, the CFU/mL load ranged from 6.5×109 to 3.9×1010 while the standard indicates 106 (Figure 3), however, Gnamakoudji loads from Gbokora and Labia neighborhoods were not statistically different (p> 0.05).

Total coliforms and enterobacteria ranged between 2.2×104 to 1.7×105 CFU/mL for the first and 1.7×104 to 9.5×104 CFU/mL for the second while the expected standard is 103 CFU/mL (Figures 4 and 5). For total coliform loads in the Commerce and Labia neighborhoods, there was no statistically significant difference (p> 0.05); those in enterobacteria of the Soleil and Commerce districts also did not statistically show any difference (p> 0.05). In addition, the colony counts of the flora were also unevenly distributed. If Gnamakoudji from the Tazibouo district was more contaminated by mesophilic aerobic germs (3.9×1010 CFU/mL), the Gbokora District contained the highest yeast and mold load (1.4×107 CFU/mL); Gnamakoudji in the Grand Marche District had the highest total coliform load (1.7×105 CFU/mL) and the Soleil district, the highest level of enterobacteria (9.5×104 CFU/mL).

Pathogenic bacteria species were detected all the drinks of different neighborhoods (Figure 6). Gbokora and Grand-marche Gnamakoudji were contaminated only with E. coli with 5×105 and 4×105 CFU/mL, respectively; loads higher than the standard of 102. Other beverages from other neighborhoods contained both Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella sp with heavy loads exceeding the microbiological standards for juices and fruit drinks. The E. coli and S. aureus loads of all beverages ranged from 4×104 to 1.4×105 for the first and 2.5×104 to 5×104 CFU/mL for the second while the standard tolerated only 102 for both species. Where the microbiological standard for Salmonella sp is a total absence in 25 mL of beverage, loads of 105 to 1.4 × 105 CFU/mL were noted for Commerce, Tazibouo, Labia and Soleil samples. The burden of pathogenic species varied from one district to another. Tazibouo's Gnamakoudji was more contaminated than those in other neighborhoods; it contained both the largest E. coli and S. aureus loads of 1.4×105 and 5×104 CFU/mL, respectively. Labia's had the largest load of Salmonella sp. (1.4×105 CFU/mL). The E. coli loads of Gnamakoudji from Commerce and Gbokora were not statistically different (p> 0.05). Those in S. aureus from the Commerce and Labia neighborhoods were not as statistically different (p> 0.05). Salmonella sp (CFU/mL) contamination of Gnamakoudji from Tazibouo, Labia and Soleil neighborhoods was not statistically different (p> 0.05). The Gnamakoudji sold in the streets of Daloa is identified as a source of microbiological hazards, which would cause multiple diseases such as diarrhea, gastroenteritis, typhoid and paratyphoid fevers. Its consumption constitutes a real risk of infection or a source of food poisoning which can lead to a public health problem.

The flow diagram of artisanal production of Gnamakoudji compared with those presented in the work of Agassounon et al. (2011) and those of Ndiaye et al. (2015) on other close-up craft drinks were almost the same. Moreover, according to the work of Ndiaye et al. (2015), throughout West Africa, fruit juice and beverage product flow diagrams show the same unit operations with some differences in formulations. But, these empirical manufacturing methods do not guarantee the stability of the productions. However, the physicochemical stability and the microbiological quality of Gnamakoudji depend in particular on the raw material, the formulations and the various technological treatments including pasteurization, chemical preservatives and stabilized final pH. Physicochemistry showed that Gnamakoudji was an acidic drink. This acidity is due to the liberation of many organic acids (contained in the rhizomes of ginger in the juice (Ali et al., 2008; Park et al., 2008; Shimoda et al., 2010). The pH of this non-alcoholic beverage is satisfactory because according to CODEX-STAN 243-2003, the pH of fruit juices and beverages must be less than 4.5. With regard to the sugar content of Gnamakoudji, consumption approximately 330 mL (more than 50 g of sugar) would put the consumer at the limit of the tolerable amount recommended by the WHO (less than 50 g of sugar per day).

Over-consumption of non-alcoholic but very sweet Gnamakoudji could have adverse effects on health and lead to cardiovascular disease (Johnson et al., 2009, Yang et al., 2014), obesity (Sievenpiper et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2013), diabetes (Basu et al., 2013) and dental caries (Moynihan and Kelly, 2014). This 18% sugar content is lower than the levels that would limit microbial growth (between 65 and 67%) based on Boumendjel's work (2005). Microorganisms could therefore develop easily in said drinks despite relatively low pH. Indeed, at pH close to 4, germs are not

eliminated but have a slow growth. The microbiological study showed the contamination of Gnamakoudji by flora of deterioration and insalubrity resulting in a deficit of good production practices. Worse, pathogenic species are found there. This contamination is due, on the one hand to the process of transformation of the drink and on the other hand to the intrinsic characteristics of this drink.

According to the manufacturing process, ginger is often ground with the skin during the manufacture of Gnamakoudji. Like simple washing, no disinfection operation has been undertaken to neutralize the microorganisms of the soil on this skin. In addition, the hygienic state of mechanical grinders in community markets is never mastered. The multiplicity of products crushed by these machines could be considered as a cross-contamination site par excellence. Also, the operation of extraction of the juice would be carried out with bare hand. The hands would carry most of the germs of contamination, even faecal, when hygiene is not practiced. It should be noted, however, that the drink obtained was always packaged in jars already used or recycled; anything that does not guarantee their safety.

Moreover, according to the work of Bayoï et al. (2014), manufacturing processes greatly influence the microbiological quality of artisanal beverages. In a study on food packaging, recycled packaging is strongly discouraged as it may contaminate food (FAO, 2014b). Hygiene indicators such as E. coli, coliforms and enterobacteria have been detected at loads well in excess of standards. These germs could be responsible for serious food infections. Moreover, in the recent work of Kouassi et al. (2018), street food consumers in the same city reported gastroenteritis, diarrhea, vomiting and fevers from consuming foods such as fruit juices and drinks, or dairy products. These microorganisms indicative of a lack of hygiene have also been highlighted in other artisanal drinks by other authors such as Aawi (2000), Kruy et al. (2001) and Baba-Moussa et al. (2006).

In addition, the total absence of heat treatment throughout the manufacturing process would explain the very high load of indicator bacteria mesophilic aerobic germs in Gnamakoudji. The presence of these germs in artisanal beverages has also been reported by Mbadu et al. (2016). Poor conservation would favor the process of alteration of Gnamakoudji. Indeed, this drink is sold in coolers and jars without ice to maintain the temperature at 4°C, without omitting the phases of freezing and thawing. The breaking of the cold chain could cause the accelerated growth of certain microorganisms.

According to the work of Agassounon et al. (2006) and those of Folefack et al. (2008), in addition to manufacturing processes, the contamination of artisanal juices and beverages is also related to the socio-geographical environment of manufacture and / or sale of these juices or drinks. The fabrications were made in homes with uncontrolled environment. Under these conditions, these drinks would be subject to all kinds of contamination according to Koné (2014) in a study of the control of contamination of fresh drinks. The less acidic pH could help the growth of these germs. The presence of pathogenic bacterial species such as S. aureus, E. coli and Salmonella sp is a real danger for consumers of this drink. Apart from samples from Gbokora and Grand-marche districts, where the drinks were contaminated with only E. coli, the Gnamakoudji from the other quarters was contaminated by the three pathogenic species in combination: S. aureus, E. coli and Salmonella; anything that would not guarantee food security. Similar studies have reported not only common but also pathogenic germs in beverages (Agassounon et al., 2009; Amusa et al., 2009). The consumption of street Gnamakoudji poses a real risk of dietary infection for Daloa populations.

Street food has become unavoidable in the current development of urban catering, as is the case in Daloa. The physicochemical and microbiological analyses revealed that the consumption of the Gnamakoudji drink sold in the city of Daloa would pose a risk to the health of the consumer. High loads of coliforms, enterobacteria and mesophilic aerobic germs have been discovered. Pathogenic bacterial species such as E. coli, S. aureus and Salmonella sp even in high numbers have been detected in street Gnamakoudji. As a result, consumption poses a real danger to the health of consumers. The upstream empirical manufacturing process and the difficult sales conditions would increase the risk of contamination and growth of microorganisms. Thus, the competent authorities must inform and raise awareness of the health risks to consumers. A regulation of street food could limit the risk of contamination. Awareness of hygienic measures such as routine hand washing before and during production would reduce the risk of contamination. Adequate measures must be taken during manufacture to produce a less risky Gnamakoudji. These measures may include decontamination of the raw material with all equipment used, hot packaging, wearing gloves, heat treatment at the end of the preparation of the drink; which would limit transmissions of germs. Good communication about the dangers of eating street foods would help to improve the well-being of consumers.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Aawi A (2000). Evaluation de la qualité hygiénique des denrées alimentaires des revendeuses détentrices d'une carte de santé valide dans les écoles primaires de la ville de Lomé. Mémoire d'Université, Lomé, Togo 105 p.

|

|

|

|

Agassounon D, Tchibozo M, Toukourou F, De Souza C (2006). Identification de la flore microbienne de six plantes médicinales utilisées en médecine traditionnelle béninoise. Association Africaine de Microbiologie et d'Hygiène Alimentaire 18(53) :24-29.

|

|

|

|

|

Agassounon DTM, Ahissou H, Ahanhanzo C, Toukourou F (2009). Appréciation des qualités microbiologiques et nutritionnelles de la boisson "Bissap" issue de la technologie traditionnelle améliorée. Journal de la Recherche Scientifique de l'Université de Lomé série A, 11(1):17-25.

|

|

|

|

|

Agassounon DTM, Bada F, Ahanhanzo C, Adisso SA, Toukourou F, De souza C (2011). Effets des huiles essentielles sur les qualités hygiéniques et organoleptiques de la boisson "bissap". Review of Industrial Microbiology Sanitary and Environnemental 5(1):1-23.

|

|

|

|

|

Ali BH, Blunden G, Tanira MO, Nemmar A (2008). Some phytochemical, pharmacological and toxicological properties of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe): A review of recent research. Food Chemical Toxicology 46: 409-420.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Amusa NA, Odunbaku OA (2009). Microbiological and nutritional quality of hawked kunun (a sorghum based non-alcoholic beverage) widely consumed in Nigeria. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition 8:20-25.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Baba-Moussa L, Baba-Moussa F, Sanni A, Fatiou T (2006). Etude des possibilités de contamination des aliments de rues au Benin : Cas de la ville de Cotonou. Journal de la Recherche Scientifique de l'Université de Lomé 8(2):149-156.

|

|

|

|

|

Barro N, Ousmane O, Bello AR, Nikiema PA, Ilboudo AJ, Ouattara AS, Ouattara CAT, Traoré AS (2007). L'impact de la température de vente sur l'altération de la qualité microbiologique de quelques aliments de rue à Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso). Journal des Sciences 7(2):25-32.

|

|

|

|

|

Basu S, Yoffe P, Hills N, Lustig RH (2013). The relationship of sugar to population-level diabetes prevalence: an econometric analysis of repeated cross-sectional data. Public Library of Science 8(2):1-8.

|

|

|

|

|

Bayoï JR, Djoulde DR, Maiwore J, Bakary D, Soppe EJ, Noura B, Tcheme G, Sah RT, Ngang JJE, Etoa FX (2014). Influence du procédé de fabrication sur la qualité microbiologique du jus de «Foléré» (Hibiscus sabdariffa) vendu dans trois villes du Cameroun: Maroua, Mokolo et Mora. International Journal of Innovation and Applied Studies 9:786-796.

|

|

|

|

|

Chenouf A, Khirani A, Yabrir B, Hakem A, Lahrech BM, Houali K, Chenouf N (2014). Risque dû à la consommation des boissons rafraichissantes sans alcool édulcorées. Afrique Science 10(4):70-77.

|

|

|

|

|

Compaoré JT, Barro N, Belemsigri Z, Komkobo C, Belem MC, Yameogo C (2000). Leçons de management stratégique: amélioration du secteur de l'alimentation de rue à Ouagadougou, Burkina-Faso, 1ère Ed. Edition ONG ASMADE.

|

|

|

|

|

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (2014a). Solutions d'emballages alimentaires adaptées aux pays en développement. Rome. www.fao.org/3/a-i3684f.pdf

|

|

|

|

|

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (2014b). The Street Food Initiative in Khulna [L'initiative de vente d'aliments sur la voie publique à Khulna] [disponible en ligne à l'adresse:

|

|

|

|

|

Folefack DP, Njomaha C, Djoulde DR (2008). Diagnostic du système de production et de commercialisation du jus d'oseille de Guinée dans la ville de Maroua. Tropicultura 4(26):211-215.

|

|

|

|

|

Johnson RK, Appel LJ, Brands M, Howard BV, Lefevre M, Lustig RH, Sacks F, Steffen LM, Wylie RJ (2009). Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 120(11):1011-1020.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kone S (2014). Hygiène et maitrise de la pollution dans la fabrication des boissons artisanales consommées fraiches. Brevet de Technicien Supérieur des industries agro-alimentaires et chimiques, option contrôle, Institut Voltaire, Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire, 43 p.

|

|

|

|

|

Kouassi CK, Coulibaly I, Coulibaly B, Konate I (2018). Diagnosis and characteristics of street food consumption in a city with high population growth: case of Daloa (Côte d'Ivoire). International Journal of Science and Research 7(6):1129-1133.

|

|

|

|

|

Kouassi KA, Dadie AT, N'Guessan KF, Yao KC, Dje KM, Loukou YG (2012). Conditions hygiéniques des vendeurs et affections liées à la consommation de la viande bovine cuite vendue aux abords des rues de la ville d'Abidjan (Côte d'Ivoire). Microbiologie et Hygiène Alimentaire 24(71):15-20.

|

|

|

|

|

Kruy SL, Soares JL, Ping S, Flye SMF (2001). Qualité microbiologique de l'aliment "glace, crème glacée, sorbet" vendu dans les rues de la ville de Phnom Penh; avril 1996 - avril 1997. Bulletin de la Société de Pathologie Exotique 94(5):411-414.

|

|

|

|

|

Mbadu Z, Ntumba M, Sumba F, Benandwenga M, Ekalakala T (2016). Contrôle de la qualité microbiologique et physicochimique de la boisson artisanale Londo à base de Mondia whitei ((Hook. f.) Skeels) (Apocynaceae). Congo Sciences 4(1): 1-7.

|

|

|

|

|

Mihajlovic B, Dixon B, Couture H, Farber J (2013). Évaluation qualitative des risques microbiologiques que comportent les jus non pasteurisés de pomme et d'autres fruits. International Food Risk Analysis Journal 3(6):1-22.

|

|

|

|

|

Monrose GS (2009). Standardisation d'une formulation de confiture de chadèque et évaluation des paramètres physico-chimiques, microbiologiques et sensoriels. Mémoire de Master de l'Université d'Etat d'Haïti, option agronomie, Port-au-Prince, Haïti 60 p.

|

|

|

|

|

Moynihan PJ, Kelly SA (2014). Effect on caries of restricting sugars intake: systematic review to inform WHO guidelines. Journal Dental Research 93(1):8-18.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mpondo EM, Vandi D, Ngouondjou T, Foze, Patrice Brice Mvogo OPB, Enyegue EM, Dibong SD (2017). Contribution des populations des villages du centre Cameroun aux traitements traditionnels des affections des voies respiratoires. Journal of Animal and Plant Sciences 32(3):5223-5242.

|

|

|

|

|

Nandkangre H, Ouedraogo M, Sawadogo M (2015). Caractérisation du système de production du gingembre (Zingiber officinale Rosc.) au Burkina Faso : Potentialités, contraintes et perspectives. International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences 9(2):861-873.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ndiaye NA, Dieng M, Kane A, Cisse M, Montet D, Toure NC (2015). Diagnostic et caractérisation microbiologique des procédés artisanaux de fabrication de boissons et de concentrés d'Hibiscus sabdariffa L au Sénégal. Afrique Science 11(3):197-210.

|

|

|

|

|

WHO (2010). Mesures de base pour améliorer la sécurité sanitaire des aliments vendus sur la voie publique. Note d'information INFOSAN N° 3/2010, 6 p.

|

|

|

|

|

Park M, Bae J, Lee DS (2008) Antibacterial activity of [10]-gingerol and [12]-gingerol isolated from ginger rhizome against periodontal bacteria. Phytotherapy Research 22:1446-1449.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

RGPH (2014). Recensement Général de la Population et de l'Habitation Ivoirienne.

View.

|

|

|

|

|

Shimoda H, Shan SJ, Tanaka J, Seki A, Seo JW, Kasajima N, Tamura S, Ke Y, Murakami N (2010). Anti-inflammatory properties of red ginger (Zingiber officinale var. Rubra) extract and suppression of nitric oxide production by its constituents. Journal Medicinal Food 13:156-162.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sievenpiper JL, De Souza RJ, Mirrahimi A, Yu ME, Carleton AJ, Beyene J, Chiavaroli L, Di Buono M, Jenkins AL, Leiter LA, Wolever TM, Kendall CW, Jenkins DJ (2012). Effect of fructose on body weight in controlled feeding trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine 156(4):291-304.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Wang H, Steffen LM, Zhou X, Harnack L, Luepker RV (2013). Consistency between increasing trends in added-sugar intake and body mass index among adults: the Minnesota Heart Survey, 1980-1982 to 2007-2009. American Journal of Public Health 103(3):501-507.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Yang Q, Zhang Z, Gregg EW, Flanders WD, Merritt R, Hu FB (2014). Added sugar intake and cardiovascular diseases morality among US adults. Jama Internal Medicine 174(4):516-524.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Zah BT (2015). Impact de la migration sur la démographie en Côte d'Ivoire. Revue de géographie du laboratoire Leïdi 13:284-300.

|

|