Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

In this study, the American pianist and composer Jeff Manookian's "Etudes for the Intermediate Pianist" method was examined. In this qualitative study, the descriptive research model was employed and the literature was scanned through document review. As a result of the examination, no study was found on Manookian's piano etudes. To that end, Jeff Manookian's "Etudes for the Intermediate Pianist" method was examined by considering the characteristics and differences of the etudes, and the elements that the composer aimed to use in the etudes were stated. It is seen that each etitude in the method includes practices that will enable to overcome a different technical difficulty. Including the nuances of musical expression in the etudes and emphasizing the musical terms reveal that the composer adopted an approach that aims to care and increase musicality as well as technical development. Manookian etudes also have a writing style that supports pedal use and performance improvement. As a result of the study, it is thought that Manookian's etudes for intermediate pianists can be used as an alternative source in piano education.

Key words: Jeff Manookian, piano education, piano etudes.

INTRODUCTION

Etudes, which play the most important role in providing technical development in piano education, are musical works that handle various technical difficulties in forms larger than exercises (Pamir, n.d.). Etudes are used very effectively in the education process with both their different technical difficulty levels and the way they are applied (Kurtuldu, 2009). The concept of etude in piano literature was first used in the 18th century, and became popular in piano education in the early 19th century. This situation paved the way for the creation of new methods by gathering the etudes for amateur and professional musicians (Ferguson and Hamilton, 2005). In this period, the etudes written by composers such as Carl Czerny, Muzio Clementi, and J.Baptist Cramer in the field of piano were exemplary studies with the first method feature. These methods are still important today and are frequently used as developmental etudes at different levels of piano education.

Etudes in the literature are used in order to overcome the technical difficulties faced by the students in piano education in Turkey as well as all over the world (Alper, 2021). Etudes written especially for beginner and intermediate level are the most applied in education. In these etudes, it is aimed to ensure the independence and equality of the fingers, to teach correct finger, hand, wrist and arm positions, the octave, chord playing technique, the hand opening, the positions in the parallel, opposite and diagonal movements of the hand, to develop competencies such as legato (tied), non legato (untied), and staccato (detached) playing (Bilir, 2016). In addition to all these, etude studies in piano education are also very important in terms of developing and completing the technical-musical skills of students, increasing their sight-reading skills, and making their command of the piano sufficient (Y?lmaz, 2018).

With the development of the mechanism of the piano instrument and the piano technique, the etudes written for the piano developed over time and reached the level of distinguished works for concert purposes that require virtuosity (Tufan, 2004). Especially Chopin, Liszt, Scriabin and Moszkowski are among the composers who wrote examples of such etudes.

In piano education, the right etudes should be selected according to the student's needs, age, physical structure, proficiency, awareness and comprehension, and current level in piano education, and these etudes should be studied in a controlled manner with the educator (Y?lmaz, 2018). Etudes are better known through analysis. In this way, the perception and adoption of etudes becomes easier. Examining etudes for educational purposes will make positive contributions to the piano education process (Kurtuldu, 2009).

Kutluk (2001) and Kasap (2004), in their research, determined that Czerny, Duvernoy and Burgmüller are the most preferred etudes and exercises in institutions providing piano education in Turkey. In particular, including the same beginner and intermediate level etudes in the piano education process creates a vicious circle and causes etude studies to turn into a repetitive process (Engül and Pirgon, 2020). For this reason, it is thought that it is important to introduce new and different etudes written for beginner and intermediate level in piano education to students and to add these etudes to the repertoire. Based on this idea, it is aimed to examine Jeff Manookian's "Etudes for the Intermediate Pianist" method in this study.

Jeffrey Donelson Manookin, better known as Jeff Manookian (1953-2021), isan American pianist, composer, and conductor. He stood out as a piano prodigy in his youth and won many awards and achievements at an early age. Known for his performance and prolific composition, Manookian has written solo works and concertos for piano as well as etudes (MOA, 2021). These etudes are “Etudes for the Young Pianist” that he wrote for young pianists and “Etudes for the Intermediate Pianist” he wrote for intermediate level pianists, which is the subject of this research.

Problem

The problem of this study is to provide intermediate pianists with the Manookian “Etudes for the Intermediate Pianist” method as a source for technical and musical development.

Significance of the study

This study is of great importance in terms of introducing an alternative educational resource and a composer at the same time. It is also significant as it is an analysis of an alternative resource that can be used in both amatour and professional piano education.

METHOD

In this part of the research, the research model, universe and sample, data collection and analysis are presented.

Research model

This study, which is based on field research in instrument education, is a qualitative research. Qualitative research can be defined as “research aimed at revealing perceptions and events in a realistic and holistic way in a natural environment by using data collection techniques such as observation, interview and document analysis” (Y?ld?r?m and ?im?ek, 2008). The document analysis method used in the research is also a qualitative research method used to analyze written materials such as books and magazines, which are specified as documentary scanning and carry traces of past phenomena (Karasar, 2008).

Data collection and analysis

In the study, the literature was scanned through document review and studies on piano etudes used in piano education were examined (Poyrazo?lu 2007; Topta? and Çe?it, 2014; O?an and Albuz, 2013; Sezen, 2021; Ahmeto?lu, 2020; Öztürk, 2007; Kurtuldu, 2009; Umuzda?, 2012; Kalkano?lu, 2020; Engül and Pirgon, 2020; Alper, 2021). Document review has shown that there is no study on Manookian's piano etudes. As a result of the data obtained, it was decided to examine Jeff Manookian's "Etudes for the Intermediate Pianist" in terms of general characteristics and the elements that the composer aimed to use in the etudes. Thus, the study was limited to the Manookian "Etudes for the Intermediate Pianist" method.

After that the Jeff Manookian's Etudes for the Intermediate Pianist (Manookian, 2011) was obtained from Internet Music Score Library Project (IMSLP) website. Even though the book is not in the public domain, it has a Creative Commons license. As written in the IMLSP website: Works not in the public domain can be submitted, with the creator's permission, using a Creative Commons license.

Then all 12 etudes in the book were analyzed. First, they were all played on piano to understand the pianistic approach the composer was using. After that the whole recording of the album which was performed by the composer himself was listened to for the same reason. The following steps were followed in the analysis of each etude:

1. The technique that the etude trains

2. Finger numbering analysis

3. Interval and chordal analysis

4. Scale analysis

5. Overall lookup for distinctive features

All the data obtained are presented in the Findings section. For each etude an analysis text was written, and sheet music of important sections was presented.

FINDINGS

Information and features of the 12 etudes in the Manookian "Etudes for the Intermediate Pianist" method are here. The composer created a separate small title for each etude. In the analysis, examples of etudes are presented with figures.

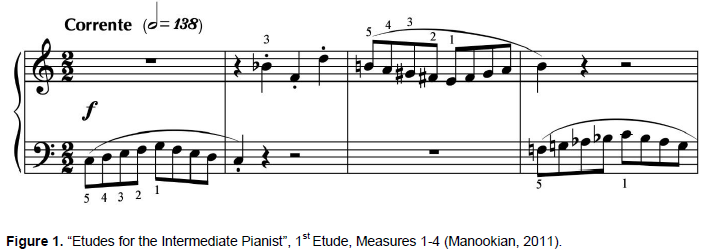

Etude No.1- Corrente

From a compositional point of view in the 1st etude, the composer focused on the repetition of five consecutive sounds over different pitches and on tonal contrasts. The first measure is in C major with eighth notes, followed by a broken arpeggio of B-flat major in the right hand in the second measure. In the third measure, the first five sounds belonging to the E Major tone appear as descending. These tonal changes, encountered in almost every measure, dominate the entire etude. This five-tone motif is embroidered with a contrapuntal writing and tonal excursions.

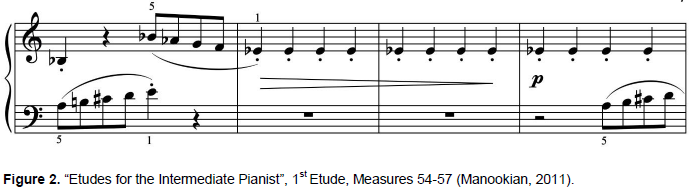

The technical structure that the etude practices is the descending and ascending sequences given in different tonalities consisting of 5 consecutive fingers (Figure 1). Another remarkable issue here is finger numbers. In traditional finger number use, 5th and 1st fingers are not preferred on black keys, except for some very fast passages. However, the composer did not follow this tradition in this study and used a different working methodology. The e flat note on page 7 (measure 55) is always taken with the 1st finger. While the use of the 2nd finger would be traditionally preferred at this tempo, the composer chose the 1st finger. It is thought that the reason for this is the absence of finger transition, which is seen throughout the etude.

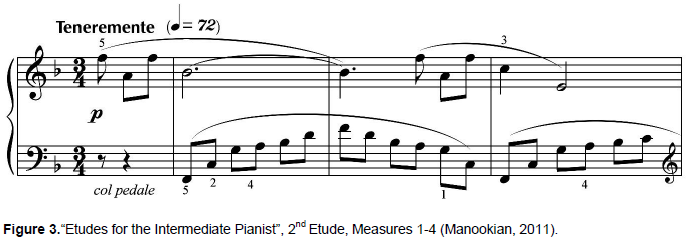

Etude No.2- Teneremente

The 2nd etude consists of the continuous repetition of 6th (interval) leap motif seen in incomplete measure and the accompaniment movement that started in the left hand in the 1st measure. When viewed harmonically, the arpeggio in the left hand in the 1st measure belongs to the F major chord (tonic) in the first four notes, while in the last two notes it is sub-dominant. Meanwhile, in the right hand, the b flat note is held as a pedal. It is seen that this situation prevails throughout the work. The composer used anticipation and apogiatural sounds harmonically and evaluated the right and left hands as non-chord tone in tonal context. In this way, it provided a harmonic coloring (Figure 2).

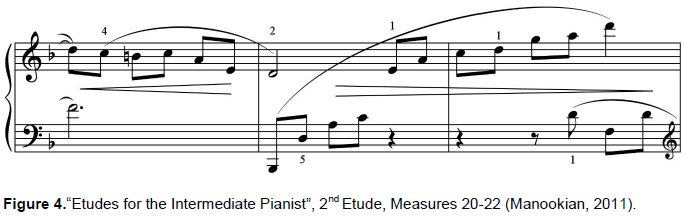

When examined technically, the etude practices large arpeggios (Figure 3). Mostly, octave arpeggios between the 1st and 3rd notes or exceeding octave arpeggios are encountered. In places such as the second line (21st measure) on page 9, it is aimed to play the transitions from left hand to right hand as if playing with one hand. In the etude, it is supported to make these transitions with the help of pedals.

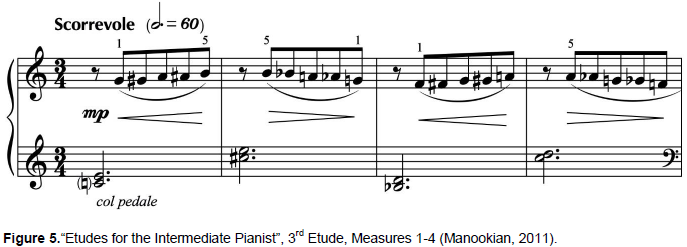

Etude No.3- Scorrevole

The 3rd etude begins with the 5 note chromatic scales appearing as ascenders and then descenders in the right hand, and the double-voiced accompaniment in the left hand. In the first three measures, a major chord relationship appears between accompaniment and scales. In the first measure, c and e notes are accompanied in the left hand, while the chromatic scale in the right hand begins with the g note, that is, the 5th of the major chord (Figure 4). This continues in the second and third scales as well. However, starting from the 4th measure, the system deteriorates and such a structure is not encountered.

With the 5th measure, the accompaniment and chromatic sequential structure, which is encountered at the beginning, leaves its place to the descending and ascending contrapuntal structures that seem like a duet between the right and left hands (Figure 5). Then, in the 15th measure, the chromatic structures pass to the right hand again, and monophonic and double-voiced accompaniments appear in the left hand. Then, the chromatic scales were extended by combining them as descending-descending, descending-ascending, and the accompaniment was transformed into wider arpeggiations. Starting from the 45th measure, the structure at the beginning was given again and the section was finished with the change of all the structures used before (scale combination, contrapuntal movements, wide arpeggios). The composer considered the use of pedals appropriate for this etude.

Technically speaking, the etude concentrates on the chromatic training of the right and left hands. In addition, another technically striking factor is that, as seen in the first four measures, the 5-note chromatic modules next to each other are played with 5 consecutive fingers. Etude mainly employs this structure, which can be practical at fast tempos. For chromatic passages of more than 5 notes, finger crossing is required. However, in some places, for example, in the long chromatic passages on the right hand of 35-36th measures, this practice is left aside and returned to classical fingering. In the 32nd measure, classical fingering is used since the left hand cannot be used consecutively in the short five-note passage (Figures 6 and 7).

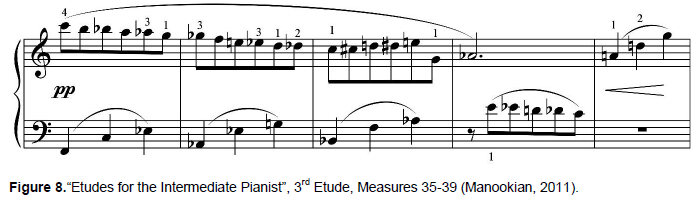

Etude No.4 –Vivace

In the 4th etude, the composer practices only the scale. However, these scales are different from the classical practice (Figure 8). Scales that are not related to each other and that do not end with a tonic sound are encountered consecutively with 1 or 2 measure structures. Rather than two hands playing together, the composer played the scales with one hand and had the other hand accompaniment. The only difference, apart from scale playing, is the hemiola type accompaniment, which we encountered for the first time in the right hand at the 17th measure. The composer used it occasionally as an accompaniment to scales.

Etude No.5- Scherzando

In the 5th etude, the composer has a finger-changing repetition (repeated note) practice. These practices are done outside of tonal harmony as much as possible. Conventional chords are not encountered (Figure 9). For example, in the first measure, the imcomplete a flat quartet immediately after the e note or the g-a flat augmented 4th that follows indicate the search for a difference. In this way, a search for tonal dissonance is encountered throughout the piece. For example, the e flat repetition on the left hand natural sound in the 5th measure can be given as an example. This etude, which is abundantly encountered with sliding harmonies, technically employs a repetition in a way thay is different than harmonic habit.

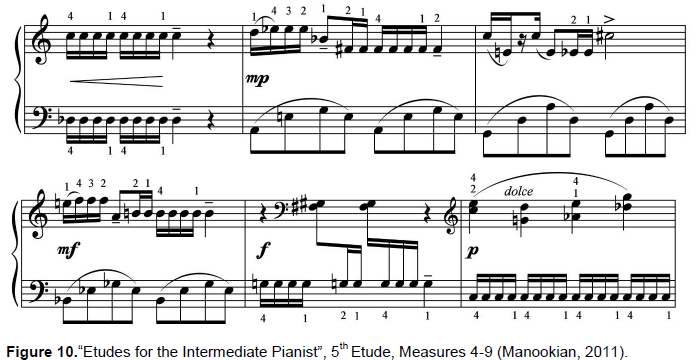

Etude No.6- Intimo

In the 6th etude, the composer focused on the division into 2 and 3 with a romantic perception, accompanied by pedals (Figure 10). A distinct practice was not done in terms of tonality, and a ballad-like piece was composed in a post-romantic language. What the composer wants to practice is the case of dividing the other hand into two in a 6/8 measure divided by 3. However, it is striking that some impressionist harmonic colors also emerged at this point. Playing the 6/8 meter by dividing it into two stands out as a structure that the early 20th century composers especially liked to use, due to the contrast it created in the rhythmic context. For this reason, the composer wanted to practice this structure.

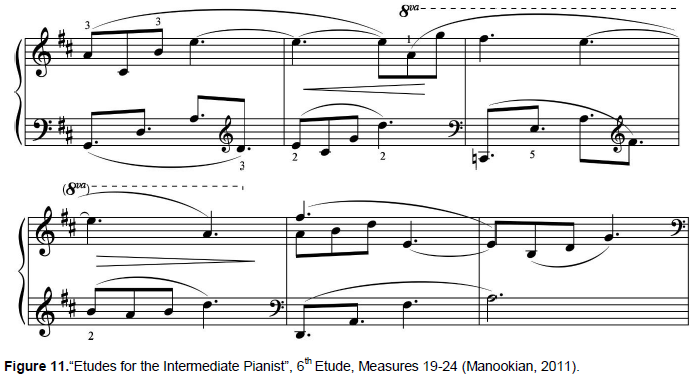

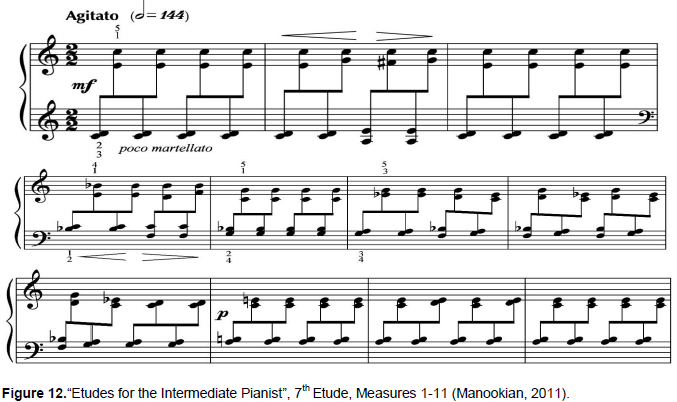

Etude No.7- Agitato

When the 7th etude is examined, it is seen that the composer focused on playing the intervals of the two hands one after the other at a fast tempo (Figure 11). This form of performance can sometimes consist of the repetition of the same sounds (1st measure), sometimes it consists of changes in the intermediate parts (2nd measure), and sometimes it manifests itself with a melodic pursuit in the upper part (7th and 8th measures). Rather than any harmonic pursuit, this two-handed alternating playing technique, which is a method frequently encountered in the works of composers such as Bartok and Saygun in the 20th century, was practiced at a very fast tempo in the piece.

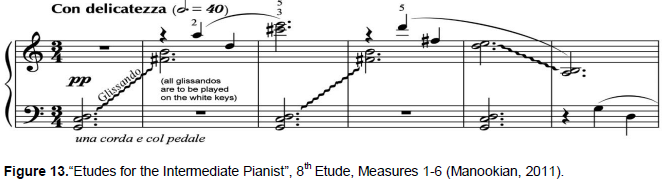

Etude No.8- Con delicatezza

The composer practices glissando in the 8th etude. In this etude, the distance between glissandos appears to be different (Figure 12). In 40 metronomes, it is necessary to perform these glissandos between structures, each at a different distance, in the right time. This shows the difficulty of the etude. The composer wanted to announce the fineness of the pianissimo playing with the help of the left pedal.

When the piece is listened to from the composer's own interpretation, it is striking that each glissando is played one beat after the beat in which it was written. However, the composer did not use any sign indicating this situation. When a pianist handles the piece, he will not be able to understand this expectation.

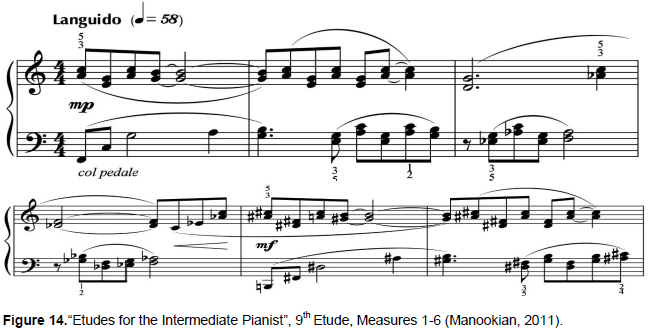

Etude No.9- Languido

In the 9th etude, the composer focused on the legato playing of the 3rd intervals, in which pedal support is provided (Figure 13). Written in an impressionistic tone, the flow of the chords is completely random. No logic is used, the search for color seems to be more dominant. This situation adds a kind of dynamism to the piece, as the sliding harmonies suddenly move to other unexpected harmonies, in line with the spirit of the piece.

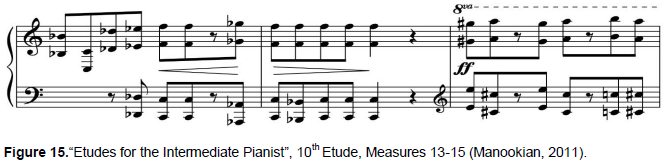

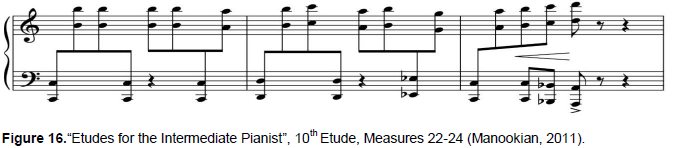

Etude No.10- Ben marcato

In the 10th etude, the composer focused on octave practices in the right and left hands. Each hand moves within itself mostly in intervals, although sometimes triple or larger intervals are seen (Figure 14). Although the piece is written in 4/4 scale, when listened or played, it is heard in 8/8 (3+3+2). Even if care is taken not to play like this in the performance, it is impossible to avoid it due to the writing and distance relations between the right and left hands.

In some places, various contrasts were created by going beyond the 3+3+2, but then this rhythmic structure was returned (measures 22-23-24). In addition, when the whole etude is examined, a writing similar to Bela Bartok's piano writing, which is defined as primitivist, is encountered (Figure 15).

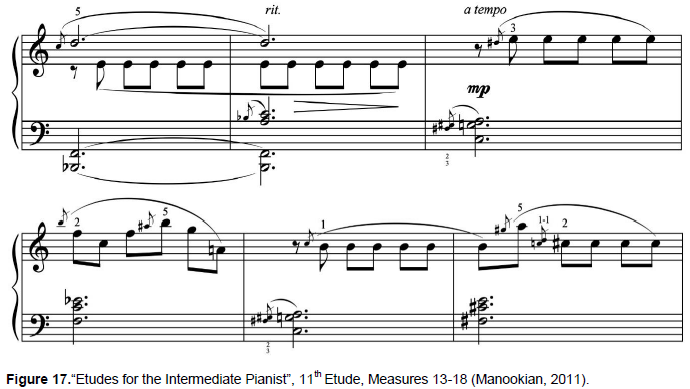

Etude No.11- Abbandonato assai

The composer focused on the grace note in the 11th etude and practiced the lower grace note, upper grace note, 2nd interval grace note on the chord (Figure 16).

All 2nd grace note on both the 2nd interval and the chord, except for one (12th measure), consist of the major 2nd interval. In order to create a contrast to the congestion created by the grace note, the composer included repetitions of sounds that can be considered close to rubato, while the chord or two sounds are longer after the grace note. These sound repetitions in the whole piece left their place to above-chord arpeggios in the 10-12 and 16th measures. The composer wanted the etude to be played with pedals a lot.

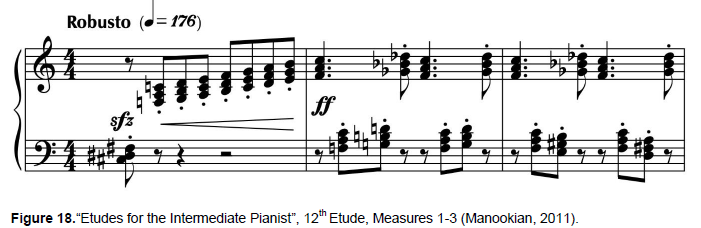

Etude No.12- Robusto

Looking at the 12th etude, it is seen that chords in root position played one after the other in the right and left hands are practiced (Figure 17). The relations of the chords with each other are based on the 2nd interval or the 3rd interval. This is because all chords are expected to be played with fingers 5-3-1. This expectation does not allow larger leaps at this pace. All consecutive chords consisting of eight notes move with a double leap, and most chords starting with a quarter or dotted quarter move with a triple leap. In addition, this etude is actually played with the wrist, not with the fingers; thus, it actually works the wrist. From a perspective, it can be considered as a wrist repetition, even if it is not on the same sound.

Since the etude is in a fast tempo, the possibility of the performer's getting tried was considered, and an intermediate section consisting of wider sounds and repetitions of the same chords was written instead of consecutive ones (Figure 18). The Bela Bartok effects encountered in some of the previous etudes are also striking here. It is thought that the composer designed a grandioso ending to the whole album, both in terms of difficulty, tempo and feeling, with this etude.

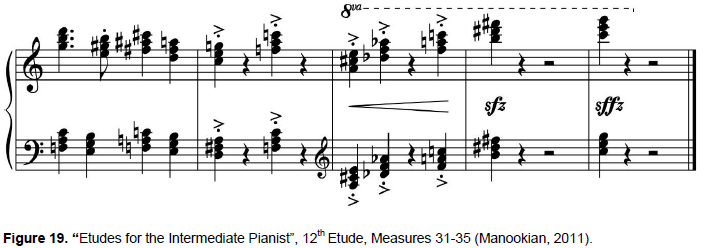

CONCLUSION

In the present study, Jeff Manookian's "Etudes for the Intermediate Pianist" method, which consists of 12 etudes, was examined by considering the characteristics and differences of the etudes, and the elements that the composer aimed to use in the etudes were stated (Figure 19).

One of the most important and primary steps to raise awareness in piano students is the analysis of the piece In the next step, the student should identify his own technical and musical deficiencies and determine which piece he needs to practice (Ahmeto?lu, 2020). Including analysis in piano education is important in terms of the possibility of positively affecting success. Therefore, revealing the general and detailed characteristics of an etude by analyzing it will positively affect the attitude and study plan of the individual. For this reason, analyzing the different characteristics of the etudes studied during the piano education process and making inferences will directly contribute to the success of the students (Kurtuldu, 2009).

It is thought that the etudes included in Jeff Manookian's method titled Etudes for the Intermediate Pianist, composed for intermediate piano education, will be of great benefit in helping both technical and musical development. Debussy's influence is on the titles of these etudes written by the composer in 1993 (Hinson, 2000). The composer indicated how each piece should be played, with small titles he wrote at the beginning of the pieces.

It is seen that each etude in the method was written in order to develop a different technique, and there are practices that will enable to overcome a different technical difficulty in each etude. Alper (2021), in his study examining Loeschorn op.65 etudes in terms of musical expression in piano education, revealed that Loeschorn etudes also have the same purpose. This situation is in parallel with the result of the current research.

It was concluded that the following techniques were used in order in Manookian studies:

Etude 1: For the five fingers

Etude 2: For wide arpeggios

Etude 3: For chromatics

Etude 4: For scales

Etude 5: For repeated notes

Etude 6: For two against three

Etude 7: For alternating hands

Etude 8: For glissandos

Etude 9: For thirds

Etude 10: For octaves

Etude 11: For grace notes

Etude 12: For chords

Incorporating nuances for musical expression in the etudes and emphasizing musical terms such as "lirico", "cantabile", "dolce", "martellato", and "grandioso" also enhance the composer's musicality. It results in an approach that aims to care and increase the musicality. Alper (2021), in his study, revealed that when compared to composers such as Czerny, Cramer, Duvernoy and Bertini, Loeschorn, etudes composed for beginner and intermediate piano education literature are those that give more importance to musical expression. This result is similar to the result of the present research.

In the study, it was also concluded that Manookian etudes are supportive etudes for improving pedal use and performance.

Ekinci (2004), in his study in which he examined the method problem related to piano education, determined that music teacher candidates greatly needed a technical practice method suitable for their level. It is thought that Manookian's etudes for intermediate pianists can be used as an alternative source in piano education.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Ahmeto?lu F (2020). Carl Czerny op. 299 piyano etütlerinin analizi, (Unpublished Master Thesis), Eski?ehir, Anadolu Üniversitesi. |

|

|

Alper A (2021). A resource recommendation for improving musical expression and narration in piano education: An examination of loeschhorn op. 65 etudes. Educational Research and Reviews 16(5):189-201. |

|

|

Bilir E (2016). F. Chopin'in Op.10 no.2 Kromatik Etüdünün Piyano Tekni?ine Etkileri (Unpublished Masters thesis). Anadolu Üniversitesi Güzel Sanatlar Enstitüsü, Eski?ehir. |

|

|

Ekinci H (2004). Müzik ö?retmeni adaylar?n?n piyano e?itimine ili?kin düzeye uygun teknik al??t?rma metodu sorunu. 1924-2004 musiki muallim mektebinden günümüze müzik ö?retmeni yeti?tirme sempozyumu Pp.7-10. |

|

|

Engül DD, Pirgon Y (2020). Ludvig Schytte Op. 108 Kleine Piyano Etüt Kitab?n?n Hedef Davran??lar Aç?s?ndan ?ncelenmesi. Sanat E?itimi Dergisi 8(1):12-21. |

|

|

Ferguson HKL, Hamilton (2005). Study. Oxford University Press. |

|

|

Hinson M (2000). Guide to the pianist's repertoire (Üçüncü Bask?). Indiana University Press. |

|

|

Kalkano?lu B (2020). Piyano e?itiminde sol el: C. Czerny op. 718 sol el etütlerinin analizi. Turkish Studies 15(3). |

|

|

Karasar N (2008). Bilimsel ara?t?rma yöntemi (17.Bask?). Ankara: Nobel Yay?n Da??t?m. |

|

|

Kasap TB (2004). Müzik ö?retmeni yeti?tiren kurumlardaki yard?mc? çalg? piyano dersleri üzerine bir ara?t?rma, 1924-2004 Musiki Muallim Mektebinden Günümüze Müzik Ö?retmeni Yeti?tirme Sempozyumu, Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi, Isparta. |

|

|

Kurtuldu M (2009). Czerny Op. 299 30 numaral? etüde yönelik teknik ve biçimsel analiz, Mehmet Akif Ersoy Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi (1):28-38. |

|

|

Kutluk Ö (2001). Türkiye'deki müzik ö?retmeni yeti?tiren kurumlarda piyano e?itimi, (Unpublished doctoral thesis), Ankara: Gazi Üniversitesi. |

|

|

Manookian J (2011) Etudes for the young pianists, Windsor Editions. Available at: |

|

|

MOA (2021). Jeff Manookian, Available at: |

|

|

O?AN FD, ALBUZ A (2013). Carl czerny op ?n p?ano teach?ng. 599 and jean-bapt?st duvernoy op. 176 effects of etues ?n the methods of the class?c per?od sonat?ne performance. Turkish Journal of Social Research 19(1):397-426. |

|

|

Öztürk B (2007).Carl Czerny'nin opus 299/19 numaral? etüdünün piyano e?itimine yönelik analizi, GÜ, Gazi E?itim Fakültesi Dergisi 27(2):241-258. |

|

|

Pamir L (Tarihsiz). Ça?da? Piyano E?itimi. ?stanbul: Beyaz Kö?k Yay?nlar?. |

|

|

Poyrazo?lu E (2007). Carl Czerny'nin Ya?am? ve il primo maestro di pianoforte etütlerinin incelenmesi, (Unpublished master thesis), Eski?ehir: Anadolu Üniversitesi. |

|

|

Sezen H (2021). Czerny'nin op.849, 30 etudes de mécanisme kitab?n?n çal?m teknikleri ve kazan?mlar? aç?s?ndan incelenmesi". ?dil Dergisi 10(77):18-30. |

|

|

Topta? B, Çe?it C (2014). Carl Czerny op.599 etüt kitab?nda sol el e?lik yap?lar?n?n incelenmesi. E-Journal of New World Sciences Academy 9(2):66-83. |

|

|

Tufan E (2004). Geleneksel Makamlar Kullan?larak Yaz?lan Etütlerin Piyano E?itimi Aç?s?ndan Önemi. Gazi Üniversitesi Gazi E?itim Fakültesi Dergisi 24(2):65-77. |

|

|

Umuzda? MS (2012). Carl Czerny opus 299 34 numaral? etüdün teknik ve armonik analizi. International Journal of Human Sciences [Online] 9(2):1569-1580. |

|

|

Y?ld?r?m A, ?im?ek H (2008) Sosyal bilimlerde nitel ara?t?rma yöntemleri (6. Bask?) Ankara: Seçkin Yay?nc?l?k. |

|

|

Y?lmaz ÖB (2018). F. Chopin op. 10, 12 no'lu "ihtilal" etüdünün piyano tekni?i yönünden incelenmesi ve piyano e?itiminde ileri düzey piyanistlik becerilerine olan katk?lar? (Unpublished master thesis). Uluda? Üniversitesi E?itim Bilimleri Enstitüsü. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0