ABSTRACT

The prevalence of academic procrastination has long been the subject of attention among researchers. However, there is still a paucity of studies examining language learners since most of the studies focus on similar participants such as psychology students. The present study was conducted among students trying to learn English in the first year of their university education. 144 male and 169 female students from four different Turkish universities participated in the study. The main purpose of the study was to investigate the relationship between the procrastination levels of language students and variables like gender, department, age, self-reported motivational levels, and satisfaction with majors. The findings of the study suggested that men reported significantly higher procrastination behavior. The participants who reported higher motivation procrastinated less while age was not found to be related to procrastination.

Key words: Academic procrastination, motivation, language learning, academic procrastination.

Procrastination, a destructive affliction that can be seen in every aspect of life, may hamper people’s career, study or personal life (Beswick et al., 1988). Ackerman and Gross (2005) defined procrastination as ‘the delay of a task or assignment that is under one’s control’ (p. 5). Alternatively, some researchers perceive it as a tendency to postpone a task that is necessary to reach a goal in spite of an awareness of negative outcomes (Lay, 1986; Steel, 2007). The procrastinator obtains a short-term relief through easier, quicker and less-anxiety provoking acts (Boice, 1996). Hence, procrastination is considered mostly as a self-handicapping propensity while procrastinators are often described as lethargic people who tend to waste time and show poor performance (Chu and Choi’s 2005).

Past researchers (Mann, 2016) identified two types of procrastination: behavioral procrastination, which can be defined as the delay of the completion of tasks, and decisional procrastination, which is concerned with postponing decision-making within some specific period. While the former focuses on how people perform tasks in different life situations, the latter appears to indicate how they approach their decision-making processes. The present study focuses mainly on behavioral procrastination.

Although, procrastination is generally accepted as a detrimental tendency, not all researchers focus on the negative aspects of procrastinatory behavior. Chu and Choi’s (2005) classification of procrastinators as active and passive displays a different approach to the perception of procrastination. They stated that, while passive procrastinators tend to postpone tasks without originally intending to do so, active procrastinators defer tasks intentionally since they work better under pressure. Chu and Choi’s (2005) also reflected that active procrastinators shared more with non-procrastinators because of their intentions of meeting the deadlines and performing the task satisfactorily. They had the control of their work and time as well as self-efficacy. Similarly, a study by Cao (2012) found that graduate students, identified as procrastinators did not always lose control of their work since they tended to procrastinate when they felt more confident with their abilities to accomplish academic tasks. Nevertheless, the bulk of the procrastination research findings focuses mainly on its detrimental effects and does not consider any of its functional aspects.

Procrastination is known to be prevalent within the academic contexts. As detected in a study conducted by Klassen et al. (2008), it took longer for procrastinators to begin important assignments. In addition, they were less confident in their capability of regulating their own learning that resulted in lower class grades and lower GPAs. A number of researchers (Cao, 2012; Perrin et al. 2011) have examined the procrastinatory behaviors of college students. In a study conducted by Solomon and Rothblum (1984), students reported that they procrastinated on writing a term paper (46%), studying for exams (27.6%), and reading weekly assignments (30.1%). Such delays within the academic context are labeled academic procrastination. Steel and Klingsieck (2016) defines this term as ‘to voluntarily delay an intended course of study-related action despite expecting to be worse off for the delay’ (p. 37). The term “student procrastination” has been used interchangeably with the term “academic procrastination”.

The relationship between procrastination and academic performance has been examined in a large number of studies. Although, some researchers have not identified any negative relationships between procrastination and academic achievement (Lay, 1986; Pychyl et al., 2000), a large number of studies have reported negative effects of procrastination on learning and achievement (Burka and Yuen, 1990; Cao, 2012; Knaus, 1998; Onwuegbuzie, 2000; van Eerde, 2003). As suggested by Kim and Seo (2015) in their meta-analysis pertaining to the relationship between procrastination and academic performance, the inconsistent results may have stemmed from different reasons such as the use of small samples, different measures, self-report data or different demographic characteristics of the learners.

After a thorough examination of the related literature, Steel (2007) classified the causes and correlates of procrastination under four major sections: task characteristics, individual differences, outcomes and demographics. Task characteristics are related to the nature of the task whereas, individual differences are clustered into different components: neuroticism, trait extraversion, agreeableness, intelligence/aptitude and conscientiousness. The outcomes are listed as mood and performance, considering procrastination may affect the students’ anxiety levels as well as their success levels. Steel also reported three possible demographic factors that can be associated with procrastination: age, gender and year. That is, people are likely to procrastinate less as they get older and when gender differences are taken into consideration, it is observed that men tend to procrastinate more. The year of the study is also an important factor since newer studies find higher levels of procrastination.

Other researchers have linked procrastination to a large number of factors such as perfectionism (Burka and Yuen, 1990; Flett et al., 1992; Hewitt and Flett, 2007), personality traits such as self-esteem, self-regulation and self-efficacy (Klassen et al., 2008), metacognitive beliefs (Fernie and Spada, 2008) and motivation (Katz et al.,2014). Among all the factors, motivation has an important place since a large number of studies focused on the correlation between motivation and academic procrastination. According to the Temporal Motivation Theory (TMT), procrastination is more likely to occur if the outcome of an unpleasant activity like writing an essay proposes rewards in the distant future (Steel and Klingsieck, 2016). Similarly, ÇavuÅŸoÄŸlu and KarataÅŸ (2015) indicate that both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations are direct predictors of academic procrastination.

The role of gender in procrastinatory behavior has been explored in a number of studies. In a study conducted by Özer et al. (2009), significant gender difference was found, with men procrastinating more (2009). Van Eerde (2003) detected only a weak relationship between gender and procrastination, with men showing procrastinatory behaviors slightly more than women. Similarly, Steel (2007) found that men procrastinated slightly more than women did, yet, the difference was not significant. In their study, performed with Turkish participants, Klassen and Kuzucu (2009) concluded that adolescent boys were more likely to spend their time with electronic media (watching TV, emailing, going on-line, and, in particular, playing computer games), while girls were most generally expected to read books, magazines and newspapers.

The present study examines the academic procrastination of language learners. The main impetus for the study came from the scarcity of studies in the literature on the academic procrastination of language learners. Hence, the main purpose of the study is to examine the academic procrastination levels of language learners. Learning a foreign language requires hard work and dedication, especially if the students do not live in a country in which the target language is the medium of communication. As in the case of the English language learners in Turkey, in such situations, the students do not find the opportunity to communicate with native English speakers. To improve their language skills, they need to fulfill many tasks such as listening to audio materials, reading texts of different levels, writing essays in English or performing speaking activities in and outside of the class. Since language learning requires the fulfillment of so many tasks, an examination of the procrastinatory behaviors of language learners may shed light on the language learning behaviors of students.

In addition to a number of factors such as study field, gender, age and self-reported motivation, the study also examined the effect of the students’ satisfaction with their majors on their procrastination scores. Here, it is crucial to give information on the National University Entrance Exams (UEE) in Turkey. Since this exam is rather competitive, students do not always have full control on the subject they will study. Their scores in the exam is the major determiner of the university, faculty and department that they will attend. Since a large number of students take the test every year and it requires hard work to get a high score, the students may sometimes end up with a field they do not actually want to be. Most of the time, these students continue their education because of not having a better option. This has been considered among the factors that may affect the procrastination scores of students. Therefore, students’ satisfaction with their majors was one of the variables that have been examined in this study.

The present study aims to investigate the procrastination levels of English language learners attending the language classes in four universities in the Southeastern Region of Turkey. The following research questions have been sought within this study:

1. What level of academic procrastination do the language learners have?

2. What is the nature of the relationship between the students’ majors and their procrastination scores?

3. Do the students’ academic procrastination scores correlate with factors such as gender, age, self-reported motivation and satisfaction with their prospective fields of study?

Participants

The participants of the study were college students that were enrolled in different departments: Economics, Turkish Literature, British Literature, English Language Teaching, Engineering (Computer Engineering, Mechanical Engineering, Electronic Engineering, Civil Engineering, Bioengineering, Metallurgy Engineering), Philosophy, History of Art and Anthropology. According to the regulations in Turkish universities, if students are to take some (or in some cases all) of their lessons in English during their university education and their language proficiency levels are not found to be adequate after a language test, they are offered English courses for one year at the beginning of their university education. Therefore, during the year in which the study was conducted, all participants were language learners, trying to improve their language skills for their future studies. After that year, they would be taking courses about their majors partly or fully in English. Namely, although they were enrolled in 13 different departments, their focus of study was English during the time of the present study. All the students attending the preparatory language classes in the four sample universities were included in the study. All responses were submitted anonymously. Altogether, 319 submissions were made, which were then reduced to 313 (144 males and 169 females) after discarding the questionnaires that were either incomplete or carelessly completed (e.g. choosing the same option throughout the questionnaire). The average age of the participants was 22.4, with a range of 17 to 31 years.

Instruments

Data was collected through a questionnaire, adapted from two scales: Aitken Procrastination Inventory (Aitken, 1982; Ferrari et al., 1995) and Academic Procrastination Scale (Çakıcı, 2003). The questionnaire, originally written in Turkish, consisted of 16 items, each accompanied by a 5-point Likert scale. An example of the items is “Whenever I start studying English, I remember something else that I need to do” with response options 1- not at all true of me, 2- slightly true of me, 3- moderately true of me, 4- very true of me, and 5- completely true of me. The possible scores of the students ranged between 16 and 80. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of internal consistency for the questionnaire was 0.88, which was acceptable. Before the administration of the questionnaire, a pilot test was conducted with twenty students, chosen according to the same criteria for the participants of the study. With the information obtained from the pilot testing, minor wording changes were made to avoid ambiguity and confusion.

In addition to this questionnaire, a background questionnaire was also prepared to obtain demographic information about the participants, including questions about their motivation levels and satisfaction with their majors. The students were asked to state their motivation levels towards learning English by choosing among three options, ranging from low motivation to high motivation. Similarly, the students were asked to determine their satisfaction with their majors by choosing among three options ranging from not at all satisfied to completely satisfied.

Procedures

The questionnaires were administered in four different universities during the spring term of 2014-2015 academic year. Only the students enrolled in a language preparation class were included in the study. The participants were assured of anonymity and it was made clear that the participation was voluntary. Since the questionnaires were administered by course instructors, the response rate was high. The questionnaire results were analyzed with SPSS.

The first research question this study addressed was on the level of the language learners’ academic procrastination. The possible mean scores for the questionnaire range from 16 to 80. The participants of this study obtained scores from 18 to 76 (M= 44.75). Appendix 1 summarizes the frequencies and percentages of all the answers given to the items in the questionnaire. According to the results, the participants find time to go over the subjects that they have learnt before English exams (Item 4; very true of me: %26.3; completely true of me: 33.1%). Nevertheless, they may put off studying boring things until the last minute (Item 8; M= 3.22; very true of me: 14.7%; completely true of me: 23.8%). The answers given to the items about the submission of assignments showed that the students generally completed their English assignments and projects on time and they did not fail to submit them. For instance, the answers given to Item 15 reflect that only 13.6% have difficulties in completing their assignments on time (very true of me: 4.5%; completely true of me: 9.1%). Similarly, the responses given to Item 11 reflect that the students submitted their assignments on time (M= 2.04; very true of me: 21.2%; completely true of me: 42.2%). However, the answers given to Item 2 suggest that they generally delay their English assignments/projects until the last minute (M= 3.47; very true of me: 19%; completely true of me: 28.3%).

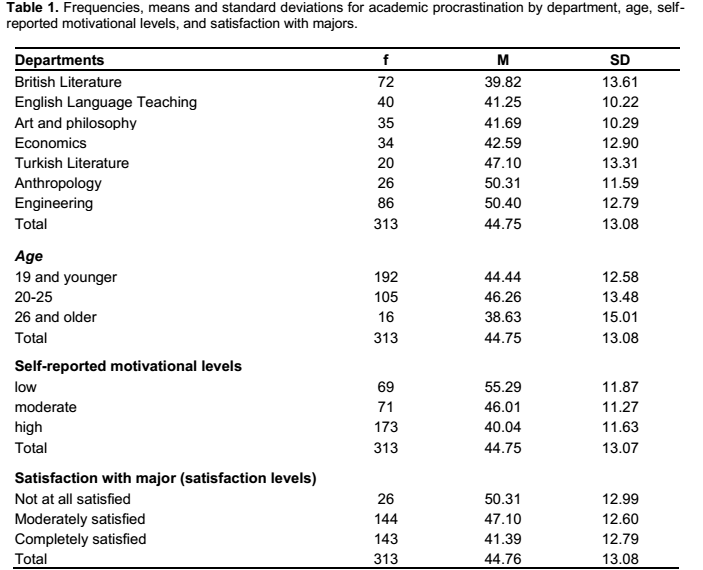

The examination of the procrastination scores of the students from different departments indicated that the lowest mean scores belonged to the departments of British Literature and English Language Teaching (Table 1). Since the data would be difficult to interpret otherwise, the scores of the students from the departments of engineering (Computer Engineering, Mechanical Engineering, Electronic Engineering, Civil Engineering, Bioengineering, Metallurgy Engineering) were examined together and the students in this group had the highest procrastination scores of all groups (M= 50.40, SD = 12.80). According to the results of the one-way ANOVA, the difference between groups was statistically significant [F(6,306) = 6.93, p<.001, η2=0.11]. Post-hoc Tukey HSD results indicated that the scores of the engineering students were significantly higher than the scores obtained by four other departments: British Literature (M= 39.82, SD = 13.61), English Language Teaching (M= 41.25, SD = 10.22), Art and Philosophy (41.69, SD =10.29) and Economics (M= 42.59, SD =12.90).

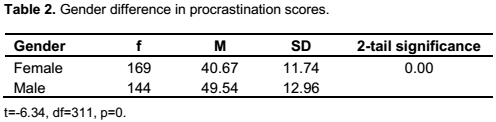

To determine the relationship between gender and procrastination scores, an independent samples t-test was calculated. As seen in Table 2, men had significantly higher procrastination scores (M= 49.54) than women (M= 40.67) [t (311) = -6.34, p<0)].

The frequencies, means and standard deviations of the participants’ academic procrastination according to age factor are presented in Table 1. Since the students’ ages were close, they were classified under three groups. The findings indicate that students who were older than 25 shared the lowest scores, followed by students that were 19 and younger while those with ages between 20-25 had the highest scores. Nonetheless, the ANOVA results did not reveal a significant difference between age and procrastination scores.

Table 1 shows the mean scores of the students with high, moderate and low self-reported motivational levels. As can be seen in the table, the students who reported having low motivation had the highest procrastination scores (M= 55.29, SD = 11.87). They were followed by the students with moderate (M= 46.01, SD = 11.27) and high levels of motivation (M= 40.04, SD = 11.63).

An ANOVA was calculated to find out whether the differences between the scores of students with different levels of self-reported motivation were significant. The results suggested a significant difference between the groups [F (2,310) = 43.13, p<.001, η2 = 0.21]. Post-hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicated a statistically significant difference among all the groups. Namely, the procrastination scores of students with high, moderate and low motivation levels differed significantly.

Another variable examined in the study was the students’ satisfaction with their majors. As Table 1 suggests, the students who were not satisfied with their majors had the highest procrastination scores (M= 50.31), while the students with complete satisfaction with their majors were less likely to report procrastination (M= 41.39). The ANOVA results indicated a statistically significant difference and a post-hoc Tukey HSD test showed the significant difference between the mean scores of the students with the highest satisfaction levels and the other two groups with lower satisfaction levels [F(2,310) = 9.95, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.06]. Here, it may be useful to mention that the motivational levels of the students differed according to their departments. The students of the departments of British Literature and English Language Teaching had the lowest mean scores (M= 39.82 and 41.26 respectively), whereas the students of the departments of Anthropology and Engineering had the highest (M= 50.31 and 50.40, respectively). The implications of these findings will be further explored in the discussion section.

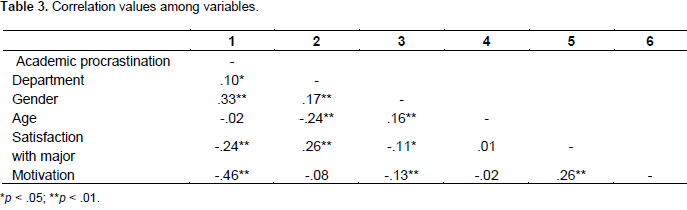

Correlations among major variables are presented in Table 3. To summarize, academic procrastination of language learners showed significant correlation with department, gender, motivation and satisfaction with major. In addition to the findings mentioned above, significant positive correlations were found between department and satisfaction with major. Furthermore, motivation appeared to be correlated with gender and satisfaction with major.

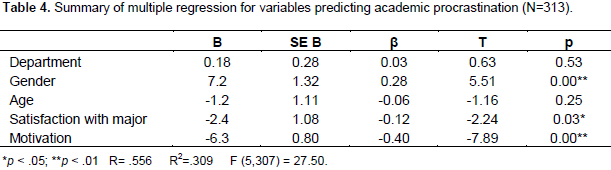

Multiple regression was used to determine the extent to which the variables predicted academic procrastination. A summary of this analysis is presented in Table 4. An examination of the standardized regression coefficients (β) revealed that the greatest contributor to the prediction model was motivation (β = -.40, p<.01). Standardized regression coefficients (β) for gender and satisfaction with major were 0.28 (p<.01) and -0.12, (p<.05) res-pectively while department and age had no significant effects.

The present study aimed to examine the academic procrastination of language learners. The students’ overall procrastination scores were not very high. They generally found time to study before their exams and submitted their assignments on time. Nevertheless, the students did admit to some form of procrastination in their academic work. Most students reported procrastinating until last minute in their study time. As suggested by Ackerman and Gross (2005), they may also submit perfunctory work as a concomitant of lagging behind. Research has shown that procrastinators have the same desire to work at the beginning of a task as others (Steel et al., 2001). However, they tend to work less to attain their goals since they devote a lot of time to do irrelevant tasks while the chief task is deferred.

As suggested by Van Eerde (2003), the role of gender on procrastination has not been consistent since quite different findings were obtained in different studies. Though many studies were equivocal in their findings and did not lead to significant results, the bulk of evidence still point to men scoring higher than women (Van Eerde, 2003; Steel, 2007; Özer et al., 2009). Not surprisingly, the findings obtained from the present study reflected that men procrastinated significantly more than women. Another study performed with Turkish participants by Klassen and Kuzucu (2009) resulted with similar findings. They explored the academic procrastination and motivation variables of 508 adolescents in a secondary school in Turkey and found that adolescent boys procrastinated more than girls. In a study conducted in

one of the prominent universities of Turkey, it was found that female students outperformed males in academic achievement, which was entailed to better class attendance, study skills and motivation (DayıoÄŸlu and Türüt-Aşık, 2007). Özer et al. (2009) attributed this difference to the behavior patterns, which may stem from culture. According to their explanation, in collectivist cultures like the Turkish culture, women may feel the need to be more organized and successful.

The self-reported motivational levels of the participants correlated negatively with their procrastination scores. In previous studies, motivation was reported to be an important factor that affected procrastination behaviors of students. Most other studies reported similar findings. Lee (2005) found that high procrastination was connected to lack of self-determined motivation along with low incidence of flow state. In another study that scrutinized the predictors of academic motivation, Kandemir (2014) found that academic motivation had a significant negative relationship with academic procrastination. Similarly, ÇavuÅŸoÄŸlu and KarataÅŸ (2015) indicated that both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations were direct predictors of academic procrastination. As known, motivation level changes according to the individual’s expectancy of an outcome. This may be connected to another finding of the study, which reflected the negative correlation between students’ satisfaction with their departments and their procrastination scores. As mentioned before, the students in Turkey do not always have full control on choosing their majors. The participants of the study were university students, who tried to improve their English proficiency levels for their prospective studies. Students who were not satisfied with their prospective majors and consequently had lower expectations concerning their forthcoming studies tended to procrastinate more than others.

This study included participants from a large number of departments, including Economics, Turkish Literature, British Literature, English Language Teaching, Engineering, Philosophy, History of Art and Anthropology. When their procrastination scores were compared, it was found that the lowest mean scores belonged to the departments of British Literature and English Language Teaching. Since learning English is more crucial for the students of these two departments, this is not surprising. This finding also strengthens the previously mentioned finding about motivation. Presumably, the students of the departments of British Literature and English Language Teaching attributed more importance to learning English, a crucial factor for them to pursue their prospective careers that led them to procrastinate less.

As mentioned by Steel (2007), people tend to show less procrastinatory behavior as they get older. In this study, age was not found to be correlated with the procrastinatory behaviors of the participants. Although, the students who were older than 25 procrastinated less than the others, this finding should be evaluated with caution since it did not lead to any significant results.

Procrastination may provide a relief in the university life with more time for socializing and release of stress(Patrzek et al., 2012). Some procrastinators may even claim that they work best under time pressure (Ferrari, 2001) and consequently, those who claim to work well under stress and time pressure procrastinate intentionally to get better results (Chu and Choi’s 2005). However, research has shown that instead of working well under pressure, dilatory students complete less of a task and display less accurate results (Ferrari, 2001). This may stem from the fact that chronic procrastinators are not good at determining the necessary time that is needed to complete a task and their tardy behavior leads to spending less time on tasks (Ferrari, 2001; Klassen et al., 2008).

The results of the present study need to be considered in light of three main limitations: First, the sample of the study consisted of university students in the southeastern part of Turkey and a larger sample could have led to different results. Second, the study is based on the students’ self-reports, which can be subjective. Moreover, it should be recognized that the study was conducted on university students, whereas different findings could have been obtained with students that had different backgrounds.

The author has not declared any conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

|

Ackerman DS, Gross BL (2005). My instructor made me do it: Task characteristics of procrastination. J. Market. Educ. 27(1):5-13.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Beswick GR, Rothblum ED, Mann L (1988). Psychological antecedents of student procrastination. Austr. Psychol. 23:207-217.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Boice R (1996). Procrastination and blocking: A novel, practical approach. Westport, Conn: Praeger.

|

|

|

|

Burka J, Yuen LM (1990). Procrastination: Why You Do It, What To Do About It. New York: Da Capo Press.

|

|

|

|

Cao L (2012). Differences in procrastination and motivation between undergraduate and graduate students. J. Scholarship Teach. Learn. 12(2):39-64.

|

|

|

|

Cavusoglu C, Karatas H (2015). Academic Procrastination of Undergraduates: Self-determination Theory and Academic Motivation. Anthropol. 20(3):735-743.

|

|

|

|

Chu AH, Choi's JN (2005). Rethinking Procrastination: Positive Effects of "Active" Procrastination Behavior on Attitudes and Performance. J. Soc. Psychol. 145(3):245-264.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Çakıcı DÇ (2003). Lise ve Üniversite ÖÄŸrencilerinde Genel Erteleme ve Akademik Erteleme Davranışının Ä°ncelenmesi. Unpublished master's thesis. Ankara: Ankara University, Institute of Educational Sciences.

|

|

|

|

DayıoÄŸlu M, Türüt-Aşık S (2007). Gender differences in academic performance in a large public university in Turkey. Higher Educ. 53:255-277.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Fernie BA, Spada MM (2008). Metacognitions about Procrastination: A Preliminary Investigation. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 36:359-364.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Ferrari JR (2001). Procrastination as self-regulation failure of performance: Effects of cognitive load, self-awareness and time limits on 'working best under pressure'. Euro. J. Personality 15:391-

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Ferrari JR, Johnson JL, McCown WG (1995). Procrastination and Task Avoidance-Theory, Research and Treatment. New York: Plenum Press.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Flett GL, Blankstein KR, Hewitt P, Koledin S (1992). Components of perfectionism and procrastination in college students. Soc. Behav. Personality 20(2):85-94.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Hewitt PL, Flett GL (2007). When does conscientiousness become perfectionism? Curr. Psychiatry 6:49-60.

|

|

|

|

Kandemir M (2014). Predictors of Academic Procrastination: Coping with Stress, Internet Addiction and Academic Motivation. World Appl. Sci. J. 32(5):930-938.

|

|

|

|

Katz I, Eilot K, Nevo N (2014). ''I'll do it later'': Type of motivation, self-efficacy and homework procrastination. Motivation Emotion 38(1):111-119.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Kim KR, Seo EH (2015). The relationship between procrastination and academic performance: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 82:26-33. doi: The relationship between procrastination and academic performance: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Klassen RM, Kuzucu E (2009). Academic procrastination and motivation of adolescents in Turkey. Educ. Psychol. 29(1):69-81.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Klassen RM, Krawchuk LL, Rajani S (2008). Academic procrastination of undergraduates: Low self-efficacy to self-regulate predicts higher levels of procrastination. Contemporary Educ. Psychol. 33:915-931.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Knaus WJ (1998). Do It Now! Break Procrastination Habit. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

|

|

|

|

Lay CH (1986). At last, my research article on procrastination. J. Res. Personality, 20:474-495.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Lee E (2005). The relationship of motivation and flow experience to academic procrastination in university students. J. Genetic Psychol. 166(1):5-14.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Mann L (2016). Procrastination Revisited: A Commentary. Austr. Psychol. 51:47-51.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Onwuegbuzie A (2000). Academic procrastinators and perfectionistic tendencies among graduate students. J. Soc. Behav. Pers. 15:103-109.

|

|

|

|

Özer BU, Demir A, Ferrari JR (2009). Exploring academic procrastination among Turkish Students: Possible Gender Differences in Prevalence and Reasons. J. Soc. Psychol. 149(2):241-257.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Patrzek J, Grunschel C, Fries S (2012). Academic Procrastination: The Perspective of University Counsellors. Int. J. Advancement Counsel. 34:185-201.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Perrin CJ, Miller N, Haberlin AT, Ivy JW, Meindl JN, Neef NA (2011). Measuring and reducing college students' procrastination. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 44:463-474.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Pychyl TA, Morin RW, Salmon BR (2000). Procrastination and the planning fallacy: An examination of the study habits of university students. J. Soc. Behav. Pers. 15(5):135-150.

|

|

|

|

Solomon L, Rothblum E (1984). Academic procrastination: Frequency and cognitive-behavioral correlates. J. Counsel. Psychol. 31:503-509.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Steel P (2007). The Nature of Procrastination: A Meta-Analytic and Theoretical Review of Quintessential Self-Regulatory Failure. Psychol. Bull. 133(1):65-94.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Steel P, Klingsieck KB (2016). Academic Procrastination: Psychological Antecedents Revisited. Austr. Psychol. 51:36-46.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Steel P, Brothen T, Wambach C (2001). Procrastination and personality, performance, and mood. Pers. Individ. Diff. 30:95-106.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Van Eerde W (2003). A meta-analytically derived nomological network of procrastination. Pers. Individ. Diff. 35:1401-1418.

Crossref

|

APPENDIX