Review

ABSTRACT

Boredom is a topic worth studying, especially the impact of boredom on college students' study is worthy of further study. This research explained the related concepts of boredom firstly. According to the research content of previous researchers, boredom was divided into external influences and internal influences. The researcher also combined the 4 variables of boredom and college students' learning attitude, academic achievement and college students' behavior to explore their relationship. The researcher hope that this kind of relationship can provide advice to educators that will affect college students from different aspects and help college students improve their academic achievement.

Key words: Boredom, learning attitude, academic achievement, behavior, college students.

INTRODUCTION

Boredom is a negative emotion experience that human beings produce in their daily lives because of lack of activity and loss of interest, which have been identity by Zhou et al. (2012). In addition, the modern environment is characterized by repetition and repression. In this environment, people will experience the feeling of boredom more frequently (Britton and Shipley, 2010; Carroll et al., 2010). Tze (2011) find out that 40% of students are bored in class according to a self-reported questionnaire. Eastwood et al. (2007) reported that 51% of teenagers are very easy to be bored. These researches indicate that boredom becomes a common phenomenon among college students.

Besides, boredom could lead to some negative effects and psychological problems. Boredom is considered a subjective experience which consists of cognition and feeling aspects (Hill and Perkins, 1985). Boredom is also mentioned in flow model by Csikszentmihalyi (1997), it is experienced when perceived challenges are below actor’s average of challenge and skills are approaching the average skill.

From multiple perspectives, such as emotion, pathology, cognition, and meaning, the effects of boredom have been studied. Most of the reason why students drop out from school comes from negative emotions – boredom, especially for middle school students (Wegner et al., 2008). Belton and Priyadharshini (2007) define that boredom is associated to antisocial behavior and ‘school failure’ (588), and even stimulate individuals to generate new thinking or action. Boredom can practically stand for danger causes, especially in young students (Britton and Shipley, 2010). The result of their research shows that people reflecting boredom has more suicidal thoughts. From the perspective of cognition, the researchers think that boredom is associated with individual cognitive failure and lack of attention. Therefore, boredom has become an important factor affecting the mental health of college students. Only by correctly understanding the boredom can an effective strategy be developed to help modern people solve various physical and psychological problems caused by boredom.

In this context, this paper presents a literature review on boredom and related concepts. In addition, the researcher put forward his own ideas about boredom affecting students' academic achievement: educators can change students' boredom state by affecting students' learning attitudes (from internal and external factors), and finally affect students' academic achievement.

BOREDOM

The concept of boredom

Ordinary, people know boredom in the role of a negative emotion, which composed of irritating, tedious, slow response, and listless. Mikulas and Vodanovich (1993) attribute boredom to a shortage inspire from the external environment and the individual’s sentiment of despondency. Researchers in different fields have defined different aspects of boredom.

Boredom syndrome

The word syndrome was originally a medical term produced by Maslow (1954) based on the overall dynamics of the term, which refers to a complex of multiple symptoms. Boredom syndrome refers to a person who shows a sense of burnout for a long time, has no psychological strength, boring, emptiness, depression, and other psychological characteristics. This group of people showed escapism, listlessness, indifference to learning and work, inability to find value of their existence, dissatisfaction with anything, and distance from others for a certain period time.

Researchers in the United States and Japan have studied boredom syndrome. Walters (1961) published a report on student apathy. Among the students he tutored, a group of people showed a phenomenon of apparent decline. The specific performance was that these students that had partial retreat reactions were not interested in class, and even refused to go to school. Kasahara (1978) also find that many students have such symptoms in cases of student counseling, he believes this is a new, apathy syndrome to retreat as the main manifestation of withdrawal neurosis.

Boredom syndrome usually has obvious external behaviors and emotional manifestations, which are present in terms of cognition, emotion, will and behavior. For instance, in cognition, they show self-centered and lack of observation; in terms of emotions, boredom individuals often report emptiness, loneliness, and more negative emotions; in the will, they always escape from reality and do not have responsibility; in behavior, there is no enthusiasm for learning and work, even avoiding people. These conditions have negative impacts on the physical and mental development of the individual.

Boredom proneness

Boredom proneness is a relatively long-lasting, personally different and stable, mainly caused by intrinsic motivation. From an individual perspective, boredom tendencies are likely to be closely related to certain personality traits. The current view is that boredom proneness mainly includes external stimulation and internal stimulation (Vodanovich et al., 2005). External stimulation refers to the inclination of individuals to pursue novelty and internal stimulation is the tendency to keep them comfortable while being interested in something.

When developing the Boredom Proneness Questionnaire for college students, the researchers discover that individuals with high boredom proneness are more likely to perceive environmental stimulation as monotonous and constrained, so they tend to use online games to seek freshness and freedom (Huang et al., 2010). People who have high boredom proneness will have the following characteristics: often experience strong loneliness, depression and tension; easy distraction during work or study, and low psychological well-being; lack of intrinsic motivation, large demand for the external environment, poor autonomy (Farmer and Sundberg, 1986).

Boredom state

Some researchers think that boredom can be divided into state-based boredom and trait-type boredom: state-based boredom which caused by specific situations, such as monotonous repetitive work or declining interest, is temporary; trait boredom, however, is long-lasting, even without tedious works (Belton and Priyadharshini, 2007; Musharbash, 2007). State-boredom, also known as responsive boredom or irritating boredom, is an experience of the individual, which leads to such boredom if they have no interest in external stimulation or cognitive skills. Early research on boredom was mainly directed at people who were forced to engage in monotonous work, such as young workers on the factory assembly lines (O’Hanlon, 1981). This state-boredom is similar to mental fatigue and sleep state (Gosline, 2007). Similar research boredom susceptibility represents ‘an aversion to repetition, routine, and dull people, and restlessness when things are unchanging’ (Zuckerman et al., 1978:140). While, trait boredom is a state of mind with personal differences also known as chronic boredom or indifferent boredom. It is close to the range of expression of boredom proneness.

Boredom in leisure

Leisure boredom means the individual cannot experience sufficient satisfaction in leisure activities and cannot get the subjective feeling of appropriate awakening (Han, 2012). When individuals are in leisure boredom, this state will be accompanied by negative emotions and cognition, lack of perceived relaxation participation, insufficient level of involvement, and no excitement, change and novel feelings. When an individual perceives that he/she is in comfortable but does not receive feedback, it will create a sense of leisure boredom. Leisure boredom will lead to the individual's participation in leisure activities, feeling meaningless, hopeless and frustrated.

Boredom in psychotherapy

In psychotherapy, boredom can occur between patients and therapists. For example, patients who talk to their feelings or seek opinions can be bored to therapist who is primarily an analytical therapist (Altshul, 1977). Similarly, when the therapist ignores emotional communication with the patient, the therapist will produce boredom emotion, and feel that now is in the ‘lay waste of powers’ (534), besides that, ‘what factors intrinsic to the therapeutic situation itself predispose the therapist to specific responses of boredom’ (534). In addition, there are macro boredom and micro boredom in psychotherapy. Macro boredom is caused during a course of treatment, and its essence is ‘a malignant countertransference neurosis’ (535). Micro boredom, however, appears more frequently. For example, when the therapist is at work, his attention suddenly shifts from the patient's confession to other things.

It can be seen that for the definition of boring, the previous researches involve a wide range and cannot give a definition of recognition, clarity and operability.

The interpretation model of boredom

Two-factor model

In the process of studying boredom, the researcher found that most of the initial researches were similar to O’Hanlon (1981), emphasizing those monotonous activities caused boredom. For the current research, this view is not comprehensive enough, so researchers have proposed a two-factor model. It is found in a survey managed by Ahmed (1990). He marks the factor which shows ‘a lack of interest in the environment’ (964) is ‘apathy’ (964), and the other factor is inattention. In a subsequent study, Vodanovich et al. (1997) use a scale to measure boredom in African American college students. The factor analysis detects that the scale was divided into eight dimensions, which can be summarized as internal simulation and external simulation. Gana and Akremi (1998) conducted boredom measurements of French college students and older people, and data analysis marks boredom as internal stimulation and external stimulation.

Gordon et al. (1997) supervise the boredom measurements of undergraduate students and workers in Australia and spot that boredom consisted of two factors, namely, inability to produce interesting activities (internal stimulation) and ‘the perception of low environmental stimulation’ (Vodanovich et al., 2005:296) (external stimulation). In summary, these studies have verified that boredom is composed of two factors.

Five-factor model

Except the two-factor model, the five-factor model is also well known. Vodanovich and Kass (1990) propose this model when do factor analysis. Five-factor is comprehended to external stimulation, internal stimulation, affective responses, perception of time, and constraint. They perform a factor analysis on BPS, and the results show that the items in the scale can be divided into five dimensions. External stimulation ‘assesses the need for sensation seeking’ (118), which the main influencing factors depend on the stimulation of the external environment. This dimension illustrates some of the characteristics of boredom tendencies associated with the outside world. Internal stimulation is related to the individual's own internal needs. It involves their entertainments and how to amuse themselves. The third dimension, affective responses, is related to emotions in which mainly correlated to boredom. Perception of time is the individual's perception and control of time in a boredom state. The fifth-dimension constraint, which mainly reflects the individual's reaction in the case of waiting, for instance, a person may respond uncomfortably because of the need to wait, or a person is very patient while waiting.

These two models actually have similarities. The two-factor model expands the concept of external stimulation and internal stimulation, categorizing the other three dimensions of the five-factor model as internal and external stimuli.

Previous researches on boredom

Boredom and attention

In the past, researchers have emphasized the close relationship between boredom and attention when defining boredom. Some researchers have introduced Continuous Performance Task (CPT) into the study to measure whether the subject responds to the stimulus. This method requires the subject to respond only to the target stimulus after the detection stimulus appears. If the probe stimulus does not appear before the target stimulus, the subject responds as an error.

Hamilton et al. (1984) detect that because this test requires participants to focus on the stimulus for a long time, he/she experiences more boredom, so individuals with high boredom tendencies are more prone to errors. Cheyne et al. (2009) examined college students' attention deficits and spots that attention deficits improved the boredom index. Danckert and Allman (2005) compare the perception of time in healthy individuals with varying degrees of boredom proneness and discover that individuals with high boredom tendencies are more likely to distract and overestimate time.

Boredom and personality traits

From an individual perspective, boredom is inclined to be closely related to personality traits. Early research on monotonous work has shown that extroverts seem to be more likely to be bored, and their demand for external stimuli is stronger than that of introverts. Culp (2006) uses the HEXACO Personality Inventory (HEXACO-PI; Lee and Ashton, 2004) to explore the boredom tendency (there is the HEXACO model in Figure 1). The results show that external stimulation is significantly negatively correlated with honesty-humility, stable emotionality and conscientiousness. While the internal stimulation shows a positive relationship with extraversion, agreeable and openness. Another study has pointed out that boredom experiences are associated with lower self-fulfillment, life goals, and narcissism (Vodanovich, 2003).

Boredom and negative emotion

Like emotions such as anger and anxiety, boredom can be seen as a specific emotion. According to Pekrun (2006), achievement emotions are described as affective related to achievement end results. In the nine aspects of achievement emotion (including enjoyment, hope, pride, relief, anger, anxiety, shame, hopelessness, and boredom), researchers pay more attention to anxiety, and other types of achievement emotions are ignored, especially boredom. Camacho-Morles et al. (2019) find that adolescents in computer-based collaborative problem-solving activities are obtained those low-capable students in math experienced more anger and boredom. Clinically, boredom and depression, anxiety, is very similar in performance, but the result of psychological measurements shows they are different. Clinically, boredom and depression, anxiety is very similar, but the results obtained by psychometrics show that they are different in essential.

Farmer and Sundberg (1986) thinks that boredom is different from other negative emotions in terms of traits and intensity. Boredom is less intense than depression.

From the environment, boredom is caused by a static environment. As well, Eastwood et al. (2007) find that individuals with high boredom tendencies have the characteristics of alexithymia, their ability to recognize and describe emotions is low, and their perception of the external environment is lower than the population who do not have boredom proneness.

Therefore, the state of boredom is very complicated. In this study, the researcher will define two aspects of boredom: boredom is divided into boredom caused by external stimuli and boredom caused by internal stimuli. The boredom duration of external stimuli is short, and it is a passive state, which is related to the external environment and stimulus; the boredom caused by internal stimuli belongs to the essential characteristics of the individual, and the duration is relatively long and stable. Once an individual can clearly understand the nature of boredom, people can think about ways to eliminate boring and achieve their own goals, especially in education.

Measurement

Previous researchers have designed some boredom scales based on their research fields and objects. This study introduces the scales that are often used in some studies.

Boredom proneness scale

The Boredom Proneness Scale (BPS) is a self-reported scale compiled by Framer et al. (1986), with a total of 28 items. The initial version was a true-false answer for each item and was later revised to the Likert 7-point scale by Vodanovich et al. (1990). It is currently the most widely used and most complete scale in the study of boredom variable. But it also has shortcomings. When many researchers use BPS data for factor analysis, there are cases where the dimensional structure is inconsistent. On the other hand, it is instability that led researchers to discover the two-factor model and the five-factor model. Later, Vodanovich et al. (2005) revised the BPS into 12 questions, divided into two dimensions of external stimulation and internal stimulation, and tested the employees of 787 companies, which proved that the theoretical model was established. The results of Huang et al. (2010) also support this theoretical model, but the difference is that they get the second-order model of the model, including six second-order factors: monotonicity, loneliness, tension, restraint, creativity and self-control.

Boredom proneness questionnaire for college students

The Boredom Proneness Questionnaire for College Students (Huang et al., 2010) is specifically for measuring college students’ boredom proneness. It has two dimensions which is mentioned in the research by Vodanovich et al. (2005): internal stimulation (including self-control and creativity) expresses boredom intrinsic motivation and the ability of individual; and external stimulation, including monotonicity, loneliness, tension, and restraint, expresses boredom tendencies to external features and the resulting emotions and behaviors. In this questionnaire, monotony is the most important factor affecting students’ boredom. Also, to reach this conclusion: Vodanovich et al. (1997) indicate that the rumpus is an important factor causing individuals’ boredom; Ahmed (1990) argues that monotony leads to an individual's lack of interest. In addition, the two dimensions of monotonicity and restraint also reflect the perception of environmental stimuli by highly boredom proneness people. However, there are only two items in this dimension of creativity, which may lead to a decrease in the reliability of the dimension when the researcher uses it.

Learning-related boredom scale

This scale is a subscale related to boredom emotion in the Achievement Emotions Questionnaire (AEQ; Pekrun et al., 2002, 2011). There are 8 items in total and using the Likert 5-point scale for the subjects to choose. Academic boredom is an emotion associated with academic activities or academic achievement.

The boredom susceptibility scale

To evaluate boredom in experience, researcher complied a scale named the Sensation Seeking Scale (SSS; Zuckerman, 1979). In this scale, the most widespread one is the subscale named the Boredom Susceptibility Scale (BS; Zuckerman, 1979). Each of its items has two opposite options for the participants to make a choice. There are two versions of the BS, Form IV and Form V (Zuckerman, 1979). The commonly used version is BS Form V, which has 10 items, distinct with Form IV which has 18 items, each item has two options, and the member who has invited to the survey chooses one of the two options. But this scale can only measure one aspect of boredom (caused by lack of environmental stimulation). Still, this scale is one of the most basic measures to calculate boredom emotions.

Other boredom scales

Single-item measure is a method of measuring boredom that was used by researchers (Shaw et al., 1996). But this method is difficult to achieve desirable levels of its reliability and validity, so it was not often used by researchers in the 1990s.

There are some scales to measuring boredom in different fields. The Job Boredom Scale (JBS; Grubb, 1975) is used to measure boredom when working or boredom according to a job. It has two subscales, but it does not give the reliability by the author. Another scale for boredom in job is Lee’s Job Boredom Scale (LJBS; Lee, 1986). These two scales primarily assess the boredom of monotonous or repetitive work and both of them show that boredom is negatively significant with job satisfaction. However, in terms of applications, few researchers pay attention to these two scales.

Although the focus of the two scales is on the boredom state of the working situation, more relevant research is needed to test the two scales and determine the scale in practical applications. If they get good proof, these two scales may become important questionnaires in job boredom (Hackman and Oldham, 1976).

There are the Leisure Boredom Scale (LBS; Iso-Ahola and Weissinger, 1990) and the Free Time Boredom Scale (FTB; Ragheb and Merydith, 2001) for researchers to quantify boredom surge from free time. The LBS has 16 items to test people’s feeling in their free time and the FTB is mainly to measure boredom in leisure with 33 items. These scales primarily measure how individuals jugged and utilize free time. Vodanovich (2003) points out this scale are better use on population who are jobless or stop working.

The scale for clinical treatment is the Sexual Boredom Scale (SBS) compiled by Watt and Ewing (1996), which is used to measure the sexual boredom experience of individuals in daily life, mainly for clinical treatment and consultation. It has 18 items and uses a 7-point Likert scale.

Judging from the existing boredom scales, the boredom variable has multiple dimensions. So, the researcher suggested that future boredom scales should take into account the various dimensions.

Boredom as an important factor of performance

Boredom is the cause of poor academic achievement. In this part, the researcher shared some relevant theories and research. Thus, the research hypothesis of this study is obtained.

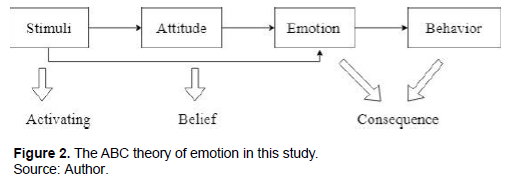

Theoretical basis: ABC Theory of Emotion

There are many theories related to emotions. Breckler (1984) studied and summarized the views and opinions of previous researchers, and believes that the three factors of affection, behavior and cognition constitute attitudes, and these three factors have mutual mediator effects. Breckler’s research perspective proves the ABC theory of emotion developed by Ellis (1957). Ellis (1957) believes that the root cause of the individual's bad emotions is not the induced event itself, but the individual's possession of the induced event. It is the basic content of emotional ABC theory. In this theory, A (Activating) represents an induced event; B (Belief) represents the individual's relevant beliefs about the event; C (Consequence) represents the individual's psychological emotions and corresponding behaviors in the event. The individual's belief in the event actually symbolizes the individual's attitude towards the event. Human’s emotions are not caused by a certain induced event itself. The generation of emotions requires a process in which stimuli cause individual beliefs and ultimately emotions. In addition, the individual itself will directly generate a certain emotion because of an event similar to the previous experience (Figure 2). In this study, the origin of emotions is stimulation, which is an external condition and is outside the scope of this study. Next, the researcher introduced the relationship between the three variables for attitude, emotion (specifically boredom) and behavior.

Boredom and attitude

Attitude is a learning tendency that is influenced by past experience. Primary school students' poor learning attitudes (such as attitudes toward assignments) can lead to negative emotions that affect their academic achievement (Shang and Qu, 2019). Poor learning attitudes are an important factor in the negative emotions of students with poor grades (Yu and Dong, 2005).

Boredom and behavior

Boredom as a negative emotion is often associated with problematic behavior, also known as social maladaptive behavior. For example, binge eating, gambling, alcoholism, drug abuse, television or internet addiction. Zhu et al. (2019) conducted a survey of 615 college students and expose that students with high boredom tendencies are more likely to become addicted to the Internet. Besides, negative emotions reduce the frequency of positive behavior. Negative emotions can affect employees' work behaviors, minimize their work behavior and increase their deviate behavior (Rodell and Judge, 2009). Patterson and Pegg (1999) have detected that high boredom minors (especially males) have a tendency to alcoholism. This group of people is at higher risk of depression and who are more likely to commit suicide.

Wegner et al. (2006) inquiry the relationship between casual boredom and risk behavior and obtain a significant positive correlation between the two parts.

Attitude and behavior

Attitudes and behaviors are closely related, which has been proposed by Indoshi et al. (2010). They believe that attitude cannot be expressed directly, but it can be demonstrated through one's behavior. In their study, they used art and design courses to measure five groups of students and find that students would abandon the course in the state of negative emotions or ignore the existence of the course. A positive attitude helps to form good behavior, while a negative attitude can lead to inappropriate behavior (Lee et al., 2015). The negative attitudes of college students can easily lead them to make some negative choices. In addition to affecting students' behavior in learning, this kind of negative attitude also affects their behavior during internships and even work (Eymard and Douglas, 2012; Ferrario et al., 2007).

From that, the researchers proposed that learning attitude of college students can affect one’s boredom, boredom can affect their behavior, and learning attitude can influence students’ learning.

The relationship between the other factors

Boredom and academic achievement: Studies have shown that boredom, or emotions can affect academic achievement. Wenemark et al. (2011) point out those negative emotions can affect an individual's academic achievement. Malekzadeh et al. (2015) introduce the intelligent tutoring systems (ITSs) in the study, which can generate more positive emotions and produce better learning performance. It is because that artificial intelligence technology can adjust students' emotional state to match learning conditions, students will produce good performance (Jaques and Vicari, 2007). Once students have negative emotions (such as boredom) then performance will decline. So, this study proposed that boredom will negatively affect academic achievement.

Attitude and academic achievement: Learning attitude is the internal reaction tendency of learners to affirmative or negative long-term learning. Yukselturk et al. (2018), mention that beliefs and attitudes are two important factors that influence academic achievement. There are studies that prove that learning attitudes can significantly predict that students’ academic achievement. Wang and Che (2005) conducted a study of 122 undergraduate students, and the results reveal that learning attitudes and academic achievement are positively correlated. The better the student's learning attitude is the better academic achievement he/she will achieve. In the nursing profession, negative attitudes will affect the academic achievement of college students (Lee et al., 2015). Muñoz et al. (2016) discover that student's attitudes can influence their future academic achievement and it is also the major to generating emotions.

Therefore, the researchers proposed that learning attitude of college students can positively affect academic achievement.

Behavior and academic achievement: The behavior of college students is significantly related to their academic achievement. Wei et al. (2014) indicate that multi-tasking behavior of mobile phones (including making calls, sending messages, browsing the websites, playing games, browsing social networking sites such as Facebook, etc.) will reduce the quality of lectures and affect academic achievement. The researchers Kuznekoff and Titsworth (2013) divided the students into three groups to organize experiments to control the frequency of their receiving messages. The results show that the test scores of students who did not receive the messages group are significantly higher than the other two groups.

Thus, the researchers proposed that behavior of college students in learning can affect his/her academic achievement.

Framework

In order to study the influence of college students' boring emotions, the researcher combined the above research content to connect boredom; learning attitude, academic achievement and behavior, and draws the research framework of this study (Figure 3). According to theory of emotion, college student's attitude can affect their boring mood, and boredom can affect his/her academic achievement. Not only can that, learning attitude indirectly influence academic achievement through boredom. Similarly, the attitude of learning can affect the behavior of college students, and the behavior of college students can also affect their academic achievement. Learning attitude can indirectly influence his/her academic achievement through the behavior. In the process, boredom will also change the learning behavior of college students.

Boredom state and behavior are two mediators of college students' learning attitude affecting academic achievement.

SUMMARY

Due to time and economic constraints, this study is only in the theoretical research stage. The research hypothesis made in this study can be verified by questionnaire survey in the future research. Learning attitude, boredom, and behavior have mature measurement scales that can be used by researchers. In terms of measuring academic achievement, past researchers often use the student’s Grade Point Average (GPA) instead (Lavin, 1965; Pekrun et al., 2010).

Based on an analysis of previous research literature, the researcher discovered a multi-intermediary model. Through this model, it can be known that the factors affecting the academic achievement of college school students are students’ learning attitude, boredom and learning behavior, and these three factors also affect each other. Therefore, the decline in college students' academic achievement may be due to students’ poor learning attitude, and this negative attitude towards learning has led to boredom state, thus affecting academic achievement. Or the poor learning attitude leads to students' behaviors that are not conducive to learning, which leads to lower academic achievement. In the process, as an emotion, boredom can also lead students to do some behaviors that are not helpful to learning.

In addition to explaining why students’ academic achievement is lower, this model can also explain some of the phenomena of students with poor grades. On this basis, this study makes the following inferences: learning attitude of college students can affect one’s boredom, boredom can affect their behavior, and learning attitude can influence students’ learning. Other than this, boredom will negatively affect academic achievement, learning attitude of college students can positively affect academic achievement, and behavior of college students in learning can affect individuals’ academic achievement.

Therefore, thinking about improving college students' academic achievement or avoiding their lower scores can be considered from these aspects. In addition, teachers can use this model to think about whether they will make students bored during the teaching process. And when teachers design a teaching plan, they can make fun as a factor to consider. Encouraging students to take the initiative to learn, changing the boredom state of students from external stimuli, and improving students' academic achievement, these should be bore in mind to each educator.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors have not declared any conflicts of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Ahmed SMS (1990). Psychometric properties of the boredom proneness scale. Perceptual and Motor Skills 71(3):963-966. |

|

|

Altshul VA (1977). The so-called boring patient. American Journal of Psychotherapy 31(4):533-545. |

|

|

Belton T, Priyadharshini E (2007). Boredom and schooling: A cross?disciplinary exploration. Cambridge Journal of Education 37(4):579-595. |

|

|

Breckler SJ (1984). Empirical validation of affect, behavior, and cognition as distinct components of attitude. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 47(6):1191. |

|

|

Britton A, Shipley MJ (2010). Bored to death? International Journal of Epidemiology 39(2):370-371. |

|

|

Camacho-Morles J, Slemp GR, Oades LG, Pekrun, R, Morrish L (2019). Relative incidence and origins of achievement emotions in computer-based collaborative problem-solving: A control-value approach. Computers in Human Behavior 98:41-49. |

|

|

Carroll BJ, Parker P, Inkson K (2010). Evasion of boredom: An unexpected spur to leadership? Human Relations 63(7):1031-1049. |

|

|

Cheyne JA, Carriere JS, Smilek D (2009). Absent minds and absent agents: Attention-lapse induced alienation of agency. Consciousness and Cognition 18(2):481-493. |

|

|

Csikszentmihalyi M (1997). Finding flow: The psychology of engagement with everyday life. Basic Books. |

|

|

Culp NA (2006). The relations of two facets of boredom proneness with the major dimensions of personality. Personality and Individual Differences 41(6):999-1007. |

|

|

Danckert JA, Allman AAA (2005). Time flies when you're having fun: Temporal estimation and the experience of boredom. Brain and Cognition 59(3):236-245. |

|

|

Eastwood JD, Cavaliere C, Fahlman SA, Eastwood AE (2007). A desire for desires: Boredom and its relation to alexithymia. Personality and Individual Differences 42(6):1035-1045. |

|

|

Ellis A (1957). Rational psychotherapy and individual psychology. Journal of Individual Psychology 13(1):38. |

|

|

Eymard AS, Douglas DH (2012). Ageism among health care providers and interventions to improve their attitudes toward older adults: An integrative review. Journal of Gerontological Nursing 38(5):26-35. |

|

|

Farmer R, Sundberg ND (1986). Boredom proneness: The development and correlates of a new scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 50(1):4-17. |

|

|

Ferrario CG, Freeman FJ, Nellett G, Scheel J (2007). Changing nursing students' attitudes about aging: An argument for the successful aging paradigm. Educational Gerontology 34(1):51-66. |

|

|

Gana K, Akremi M (1998). French adaptation and validation of the Boredom Proneness Scale (BP).L'Année Psychologique 98(3):429-450. |

|

|

Gordon A, Wilkinson R, McGown A, Jovanoska S (1997). The psychometric properties of the Boredom Proneness Scale: An examination of its validity. Psychological Studies. |

|

|

Gosline A (2007). Bored? Scientific American Mind 18(6):20-27. |

|

|

Grubb EA (1975). Assembly line boredom and individual differences in recreation participation. Journal of Leisure Research 7(4):256-269. |

|

|

Hackman JR, Oldham GR (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 16(2):250-279. |

|

|

Hamilton JA, Haier RJ, Buchsbaum MS (1984). Intrinsic enjoyment and boredom coping scales: Validation with personality, evoked potential and attention measures. Personality and Individual Differences 5(2):183-193. |

|

|

Han D (2012). The current status and prospects of boredom research: A perspective of psychology. Heihe Academic Journal (12):173-175. |

|

|

Hill AB, Perkins RE (1985). Towards a model of boredom. British Journal of Psychology 76(2):235-240. |

|

|

Huang SH, Li DL, Zhang W, Li DP, Zhong HR, Huang CK (2010). The development of boredom proneness questionnaire for college students. Psychological Development and Education 3:308-313. |

|

|

Indoshi FC, Wagah MO, Agak JO (2010). Factors that determine students and teachers attitudes towards art and design curriculum. International Journal of Vocational and Technical Education 2(1):9-17. |

|

|

Iso-Ahola SE, Weissinger E (1990). Perceptions of boredom in leisure: Conceptualization, reliability and validity of the leisure boredom scale. Journal of Leisure Research 22(1):1-17. |

|

|

Jaques PA, Vicari RM (2007). A BDI approach to infer student's emotions in an intelligent learning environment. Computers and Education 49(2):360-384. |

|

|

Kasahara Y (1978). A new category called withdrawal neurosis-Student Apathy II. Adolescent Psychopathology and Treatment. |

|

|

Kuznekoff JH, Titsworth S (2013). The impact of mobile phone usage on student learning. Communication Education 62(3):233-252. |

|

|

Lavin DE (1965). The prediction of academic performance. |

|

|

Lee K, Ashton MC (2004). Psychometric properties of the HEXACO personality inventory. Multivariate Behavioral Research 39(2):329-358. |

|

|

Lee TW (1986). Toward the development and validation of a measure of job boredom. Manhattan College Journal of Business 15(1):22-28. |

|

|

Lee YS, Shin SH, Greiner PA (2015). Can education change attitudes toward aging? A quasi-experimental design with a comparison group. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice 5(9):90-99. |

|

|

Malekzadeh M, Mustafa MB, Lahsasna A (2015). A review of emotion regulation in intelligent tutoring systems. Journal of Educational Technology & Society 18(4):435-445. |

|

|

Maslow AH (1954). Motivation and personality (3rd ed.). New York: Harper & Row. |

|

|

Mikulas WL, Vodanovich SJ (1993). The essence of boredom. The Psychological Record 43(1):3. |

|

|

Muñoz K, Noguez J, Neri L, McKevitt P, Lunney T (2016). A computational model of learners achievement emotions using control-value theory. Journal of Educational Technology and Society 19(2):42-56. |

|

|

Musharbash Y (2007). Boredom, time, and modernity: An example from Aboriginal Australia. American Anthropologist 109(2):307-317. |

|

|

O'Hanlon JF (1981). Boredom: Practical consequences and a theory. Acta Psychological 49(1):53-82. |

|

|

Patterson I, Pegg S (1999). Nothing to do: The relationship between 'leisure boredom' and alcohol and drug addiction: is there a link to youth suicide in rural Australia? Youth Studies Australia 18(2):24. |

|

|

Pekrun R (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychology Review 18(4):315-341. |

|

|

Pekrun R, Goetz T, Daniels LM, Stupnisky RH, Perry RP (2010). Boredom in achievement settings: Exploring control-value antecedents and performance outcomes of a neglected emotion. Journal of Educational Psychology 102(3):531. |

|

|

Pekrun R, Goetz T, Frenzel AC, Barchfeld P, Perry RP (2011). Measuring emotions in students' learning and performance: The Achievement Emotions Questionnaire (AEQ). Contemporary Educational Psychology 36(1):36-48. |

|

|

Pekrun R, Goetz T, Titz W, Perry RP (2002). Academic emotions in students' self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educational Psychologist 37(2):91-106. |

|

|

Ragheb MG, Merydith SP (2001). Development and validation of a multidimensional scale measuring free time boredom. Leisure Studies 20(1):41-59. |

|

|

Rodell JB, Judge TA (2009). Can "good" stressors spark "bad" behaviors? The mediating role of emotions in links of challenge and hindrance stressors with citizenship and counterproductive behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology 94(6):1438. |

|

|

Shang XY, Qu KJ (2019). The relationship between the learning attitude of senior students and procrastination: The mediating role of academic emotions. Primary and Secondary School Mental Health Education 17:8-12. |

|

|

Shaw SM, Caldwell LL, Kleiber DA (1996). Boredom, stress and social control in the daily activities of adolescents. Journal of Leisure Research 28(4):274-292. |

|

|

Tze MC (2011). Investigating academic boredom in Canadian and Chinese students. |

|

|

Vodanovich SJ (2003). Psychometric measures of boredom: A review of the literature. The Journal of Psychology 137(6):569-595. |

|

|

Vodanovich SJ, Kass SJ (1990). A factor analytic study of the boredom proneness scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 55(1-2):115-123. |

|

|

Vodanovich SJ, Wallace JC, Kass SJ (2005). A confirmatory approach to the factor structure of the Boredom Proneness Scale: Evidence for a two-factor short form. Journal of Personality Assessment 85(3):295-303. |

|

|

Vodanovich SJ, Watt JD, Piotrowski C (1997). Boredom proneness in African-American college students: A factor analytic perspective. Education 118(2):229-237. |

|

|

Walters PA (1961). Student apathy, emotional problems of the student, 2nd ed. Appleton-Century-Crofts (New York) pp. 129-147. |

|

|

Wang AP, Che HS (2005). A research on the relationship between learning anxiety, learning attitude, motivation and test performance. Psychological Development and Education1:55-59. |

|

|

Watt JD, Ewing JE (1996). Toward the development and validation of a measure of sexual boredom. Journal of Sex Research 33(1):57-66. |

|

|

Wegner L, Flisher AJ, Chikobvu P, Lombard C, King G (2008). Leisure boredom and high school dropout in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Adolescence 31(3):421-431. |

|

|

Wegner L, Flisher AJ, Muller M, Lombard C (2006). Leisure boredom and substance use among high school students in South Africa. Journal of Leisure Research 38(2):249-266. |

|

|

Wei FYF, Wang YK, Fass W (2014). An experimental study of online chatting and notetaking techniques on college students' cognitive learning from a lecture. Computers in Human Behavior 34:148-156. |

|

|

Wenemark M, Persson A, Noorlind-Brage H, Svensson T, Kristenson M (2011). Applying motivation theory to achieve increased respondent satisfaction, response rate and data quality in a self-administered survey. Journal of Official Statistics 27(2):393-414. |

|

|

Yu GL, Dong Y (2005). Academic emotional research and its implications for student development. Educational Research 26(10):39-43. |

|

|

Yukselturk E, Alt?ok S, Ba?er Z (2018). Using Game-Based Learning with Kinect Technology in Foreign Language Education Course. Journal of Educational Technology and Society 21(3):159-173. |

|

|

Zhou H, Wang Q, Dong Y (2012). Boredom: A long and revival research topic. Advances in Psychological Science 20(1): 98-107. |

|

|

Zhu Y, Yi KL, Song YC, Liang YL (2019). The relationship between college students' boredom, subjective well-being, cognitive failure experience and online game addiction. Journal of Dali University 4(3):110-115 |

|

|

Zuckerman M (1979). Sensation seeking and risk taking. In Emotions in personality and psychopathology (pp. 161-197). Springer Boston MA. |

|

|

Zuckerman M, Eysenck SB, Eysenck HJ (1978). Sensation seeking in England and America: Cross-cultural, age, and sex comparisons. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 46(1):139. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0