Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

This study presents the results from a study [W1] funded by the Directorate General of Occupational Health and Safety, an institutional body that pertains to the Employment Council of the Regional Government of Andalusia (Spain) and Ministry of Employment and Labour (Spain). The analysis focuses mainly on the teachers who work in pre-primary, primary and secondary education in Andalusia. The aim is to discover the current situation of the educational institutions in matters of occupational safety and health, establish mechanisms to orient didactic and organisational intervention to facilitate the teaching-learning process of a prevention culture, and extract basic elements to acquire training in health and safety. To do so, an inferential and descriptive analysis of quantitative data was conducted (research methology). [W2] All of this made it possible to discover the reality of the job risk prevention culture in the schools. An especially important result in this research, in order to achieve quality education in terms of prevention, safety and health, must receive preparation in their Initial Training and later in the Teacher Centres. They must be able to evaluate the teaching-learning methodology used, the suitability of what is taught for the objective proposed, and the media and/or resources based on criteria of quality, quantity, use or interest in the classroom, as expressed in the Spanish Strategy for Occupational Safety and Health and in the Second Andalusian Plan for Occupational Health and Job Risk Prevention for teachers in public schools dependent on the Education Department of the Regional Government of Andalusia (Spain) . [AB3]

Key words: Occupational safety and health, schools, teachers, prevention culture, quantitative research.

[W1]This does not make sense

[W2]Poor English

I stopped correcting your English hereon

[AB3]Changed (Reviewer 1)

INTRODUCTION

The risk prevention culture seeks excellence in the quality of working life and is based on commitment and educational participation (Nielsen, 2004). Thus, the Community Strategy on Occupational Safety and Health, 2000-2004; 2004-2008 and 2008-2012, published a document titled “How to adapt to the changes in society and in the world of work: a new community health and safety strategy” (Jansen, 2012). This document highlights the need to produce and disseminate good educational practice codes in the areas of health and safety in schools. Thus, in order to develop a prevention culture in the educational setting, a series of aspects should be taken into account that must be present when teaching prevention:

1. A prevention culture can only occur as the result of a learning process that begins in early childhood and is maintained throughout life. At the lower educational levels, the instruction must be integrated into values education, specifically within the value of “health”. As in teaching any value, the methodology has to be transversal and present the hazards in the school itself as the first example of occupational risks.

2. We focus especially on the modality represented by vocational education due to its special link to the world of work. Vocational education should integrate prevention activities into the curricular instruction process itself and, especially, into its practical aspects. The concept would be “a job is well done if it is done safely”.

3. We understand that prevention training must be present at high levels of the educational system because of their connection to the world of work, but we make special reference to studies directed toward teacher training, due to its potential effect on children and young people’s acquisition of a prevention culture.

4. Developing a prevention culture requires a collaborative effort between the employment and educational authorities, where teacher training is included as the first link.

To address the risks and accidents that can occur while performing a future job, we must recognize that integrating prevention into the set of activities and teaching models in the educational setting is fundamental and a priority, while taking into account the social, cultural and psychophysical particularities of the agents involved (Weare and Markham, 2005). Moreover, we must study the “customs” (collective behaviours), given that they form the basis for investigating why some societies resist and maintain unhealthy risky behaviours. Safety programmes that focus on intervention in behaviours as antecedents of accidents (behaviour-based safety), reinforcing safe behaviours and providing feedback, are not a “magic recipe” or a universal solution (Miller et al., 2002).

The prevention of emerging risks, such as stress, anxiety, depression and bullying, in the educational setting requires educational actions coordinated with public health policies. For Rivara (2001), it is necessary to study these risks in an interdisciplinary way from their diverse perspectives: educational, social, psychological and ergonomic. The integration of the health and safety objectives into the set of community policies, particularly those related to employment, public health and education, must be reinforced in order to improve synergies in common objectives. This is the framework for the general course of action.

It is evident that the so-called prevention culture must be initiated in the schools, become integrated in their organisational structure, and be visible at all the educational levels and stages. We cannot talk about a comprehensive education in society if the school does not decisively intervene in values education (Young, 2014[AB1] ). Values are based on beliefs and attitudes that are learned in the early phases of life (early childhood and primary) when the learning capacity is greater. Therefore, values related to health and safety must be addressed in the classroom and school, visualised and analysed based on different patterns of behaviour, and learned by carrying out good practices that provide students with the healthiest and safest lifestyles possible. In the Rome Declaration (OSHA, 2004[AB2] ) on the integration of prevention into education and training, a request was made to the European Council on Social Issues, the European Parliament and the European Commission to contemplate taking special measures to apply the European employment guidelines to the member states, in order to guarantee that:

1. Education and training in health and safety principles are mentioned as a way to achieve safer and healthier jobs and as an important tool for improving the quality of work.

2. Qualified and quantified objectives are included in employment guidelines to prepare young people for their working life through education and training.

3. “Criteria” are elaborated for training, programmes, research and, especially, evaluation of the acquired knowledge and the appropriate modifications in behaviours and attitudes.

4. The teachers receive adequate training that is extended to guidance counsellors.

In any case, teachers must facilitate and energise students’ learning process about healthy and safe behaviours that avoid or minimise the risks around them, as established in the Second Andalusian Plan for Occupational Health and Job Risk Prevention for the teaching personnel in public schools dependent on the Education Department (2010-2014).

Another fundamental aspect of prevention in the educational setting is professional training, including continuing professional development (CPD), directed mainly to the teachers. Thus, the training must include, as a key axis, the hazards that are present in schools and guidelines for their prevention (Azeredo and Stephens-Stidham, 2003).

Finally, to achieve the effective integration of job risk prevention in the educational setting and, therefore, work toward greater occupational health and safety, it is necessary to follow a series of lines of action that the European Occupational Safety and Health Agency (OSHA, 2012) has recommended:

1. At the end of compulsory education, students must have basic knowledge about questions of health and safety at work and their importance, and about their own rights and responsibilities.

2. Students in university courses and vocational education, including business schools and other professional disciplines, will have to receive the relevant information and training in matters of OSH (Occupational Safety and Health) as part of the course.

3. Prevention training must be a comprehensive part of the preparation and organisation of work experience programmes.

4. The people responsible for making policies in education, employment and job risk prevention must cooperate to include occupational safety and health in education.

5. In the area of Education and Professional Development:

6. Policies must be adopted to guarantee that training in the area of risks is part of the teachers’ study plan for each and every student.

7. The integration of prevention in the actions, agreements and policies related to education must be promoted.

8. It is important to raise teachers’ awareness that they must contribute to guaranteeing young people’s safe and healthy initiation into their working life, and companies, schools and university departments must raise awareness of risks and their prevention through research projects, activities, studies and analyses of experiences.

Purpose

Discover new channels for job risk prevention through education, determining the factors that facilitate a prevention culture in educational institutions.

Study objectives

1. Discover the current situation of the educational institutions as training centres in matters of job risk prevention.

2. Establish patterns that clarify the didactic and organisational performance directed toward facilitating the teaching-learning process in areas of prevention.

3. Determine components and characteristics of the training directed toward preparing educational institutions in matters of job risk prevention.

METHODOLOGY

The methodological strategy used is the “survey study” (Cohen and Manion, 2007; McMillan and Schumacher, 2006 and Cea, 2001).

Quantitative data collection instrument: Questionnaire

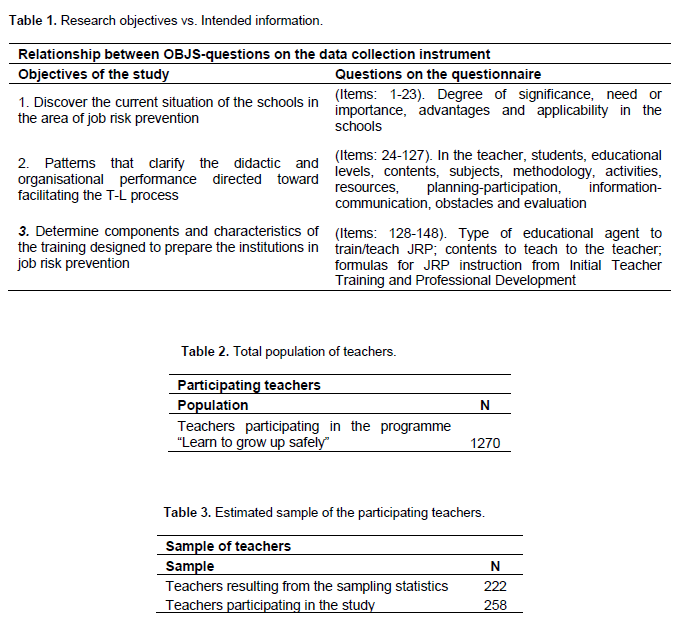

According to Cea (2001), in the survey study, the basic data collection instrument is the questionnaire (standardized). In the words of McMillan and Schumacher (2006) and Flores (2003), a questionnaire has the purpose of obtaining, in a systematic and organized way, information from the population investigated about the variables under study (Table 1).

The questionnaire applied has a Likert-type format. The interviewees are asked to respond to each statement by choosing the response category that best represents their opinion. In our case, the scale we adopted is made up of four categories (1=Not at all, 2=Very little, 3=A lot and 4=Very much), in order to avoid adopting a five-category scale with a central value represented by “Average”, as the respondents’ tendency is to automatically choose this middle value, which would not provide much information (Morales-Vallejo et al., 2003).

The questionnaire was administered in the schools in the different provinces of the region of Andalusia that participated in the campaign “Learn to grow up safely” promoted by the Ministry of Education and Employment.

Sample

The selected sample is composed of teachers participating in the Programme “Learn to grow up safely”, promoted by the Ministry of Education and Employment and carried out in the schools (Table 2).

The type of sampling used in the study is probabilistic, specifically “simple random sampling without replacement” (Lohr, 2000). We performed the calculations considering the finite population, according to the proposal by Lohr (2000) (Table 3).

Characteristics of the sample

Some initial information collected is related to the age of the teachers who make up the study sample (Table 4).

The data also show the “sex” of the teachers, presented in Table 5.

We also show the data corresponding to the “position held” by the teachers in the schools studied (Table 6):

Next, we present the teachers’ “years of experience” and the “educational levels” of the schools where they work. Table 7 and 8 show the number of years of experience of the teachers.

The data for the “educational levels” in the schools where the teachers work are located in Table 8. They are divided into four response categories: Pre-primary, Primary, Compulsory Secondary Education and “No Answer”.

In Table 9 the group of teachers is represented, organised in “teaching teams” (pre-primary and primary) and in Departments or Seminars (O.S.E).

We complete the previous information by indicating the subjects (Table 10) taught by the surveyed teachers.

We also identified the type of school, shown in Table 11.Finally, in Table 12, we present the data related to the “socioeconomic level” of the students, as perceived by the teachers in the school where they are working.

Data analysis

The use of a quantitative analytic procedure, understood as a technique to extract information from the data and interpret its meaning, using concepts and arguments supported by numbers and mathematical structures (Flores, 2003).

Thus, once the data from the questionnaire were obtained, the statistical calculations were performed with the help of the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 14.0). On the one hand, at a descriptive level, we used the central tendency measures, representing the entire distribution and the variability in order to find out how the data are grouped. On the other hand, at an inferential level, we discovered which of the differences found are due to chance and which are not. Setting a confidence level of 95% for the statements made, we developed non-parametric hypothesis contrast tests (contingency tables with chi-squared for two samples). We also carried out another more complex multivariate analysis of interdependence as the factorial analysis, ratifying the existence of different variables and groups, and that the differences between them are significant. In the contingency analysis, we considered it relevant for our study objective to cross the different dimensions and dependent variables from the questionnaire with the independent variables (identification variables of the teachers surveyed) of impact in the professional trajectory of the teacher. However, only those that were statistically very significant –with a Cronbach’s Alpha of less than 0.0005- are discussed (Lizosoain and Joaristi, 2003).

In the factorial analysis, it becomes necessary to verify a series of aspects that report on its adequacy or non-viability. The main verification statistics are:

1. The KMO –Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin- measure of sample fit (of the entire test)

2. The Bartlett sphericity test

The KMO value is .805, a value that is considered quite important, according to Kaiser (1974) (cited in Hofmann, 2010). Regarding the numeric value of the Bartlett sphericity test, it is associated with a chi-squared of 4493.294 and a p = .000, and, therefore, statistically very significant (Table 13). In this type of test obtained from factorial analysis, high indexes of consistency and reliability of the data collection instrument are also observed. To reinforce the reliability of our questionnaire, we use the split-half method and Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency method (Table 14).

After performing the split-half test, Fox (1987) indicates that when estimating responses, correlations are acceptable from 0.70 or even 0.60, when performing estimations of opinion and criticism, which is the case in the present study. The consistency coefficient with these 148 items was = 0.920, and this is a standardised coefficient that gives us a very high index of reliability between the values Fox (1987) mentioned as desirable.

Regarding the Cronbach’s Alpha internal consistency method, we obtained a Cronbach’s alpha equal to 0.946, with a confidence level of 95%, which is close to one, indicating that the questionnaire is highly reliable (Table 15). Regarding the validation of our questionnaire, a validation process was carried out by judges (Cohen and Manion, 2007). In our case, two types of judges intervened in the validation of the questionnaire: 1) experts-technicians in prevention topics (study problem) also related to the educational context; 2) consolidated researchers in the field of educational research. Moreover, the pre-test of the questionnaire was administered (Cea, 2001). We chose a small sample of individuals with the same characteristics as the study population. In our case, they were representatives of the teaching collective who perform their professional work at different levels of the educational system and have participated in or known about the prevention efforts of the educational campaign “Learn to grow up safely” funded by the Ministry of Employment and Education.

RESULTS

The results and conclusions of our study have been divided according to the different research objectives. Thus, we will present the data obtained from the descriptive and contingencies analysis.

Current situation of the educational institutions as centres for training in job risk prevention (JRP)

Objective 1

Regarding the importance and current situation of job risk

prevention in schools (descriptive level of the data), the teachers think that working on prevention in the classroom is important and necessary because, in the long term, it would be efficacious for society (90% and a mean of 3.35), and it would help to achieve the comprehensive development of the students’ personality, emotional stability (79.9% and a mean of 3.13) and preparation for life (87.6% and a mean of 3.22). The advantages obtained from integrating prevention training in schools, according to the teachers, would be to reduce accidents (86% and a mean of 3.19), foment efficacy in their future job performance (80.6% and a mean of 3.11), and encourage school children’s interaction with the environment outside the school, understood as a broad framework made up not only of people, but also of a variety of types of didactic-organisational elements (74.6% with a mean of 2.99). Regarding the level of real application of prevention in schools, the teachers consider that there are hardly any relationships with other schools for developing instructional activities on this topic (82.7% with a mean of 1.13). They also point out that the coordination and collaboration with the Administration in matters of financing and developing instructional plans is quite limited and not very practical (85.7% with a mean of 1.61). Continuing with the above, the teachers do not have the necessary resources to foment prevention in the school (83.3% with a mean of 1.72), which implies not having the possibility of working on prevention with the students (81.4% and a mean of 1.82). This means that there are numerous difficulties in trying to promote a prevention culture if they do not have the resources to plan and develop instructional activities, etc. In summary, the level of commitment of the entire staff in fostering job risk prevention in the school is rather superfluous, as the current impact of the prevention culture on the daily routine in the school is not very relevant (84.8%, with a mean of 2).

With regard to the results and conclusions arising from the contingencies analysis, a series of quite significant associations are derived that show the importance and current situation of prevention in schools. These are:

1. The teachers from 31 to 40 years old think it is very important to teach prevention in the classroom, as this content is important and necessary because in the long run it would be efficacious for society.

2. The teachers think prevention would greatly facilitate the acquisition of basic tools for students’ access to the job market.

3. The teachers who hold the position of classroom teacher think there is little commitment from the different agents in the school to fostering prevention in the school.

4. The teachers who perform duties as heads of studies state that there are no joint relationships with other schools to work on job risk prevention, and that the impact of the prevention culture in the school is quite low.

5. The pre-primary and primary teachers, along with those who belong to the mathematics, physics, chemistry, physical education, philosophy and technology departments, think it is quite advantageous to teach the prevention culture in schools.

6. The teachers who belong to public and subsidised schools think that the prevention culture currently has little impact on the reality of the school.

Keys to the development of the teaching/learning process in matters of prevention

Objective 2

To integrate job risk prevention in the teaching-learning process, it is important to take a series of factors into account. One of the basic pillars of teaching and learning is the teacher. This figure must exemplify someone who performs and transmits prevention values, foments participation in doing preventive activities, and awakens the students’ interest in contents and activities related to safety and health (90.3% and with a mean of 3.24). This means that the teacher has to facilitate, to a large extent, the students’ comprehension of the basic contents of job safety and health (89.2% and with a mean of 3.22). From a more personal perspective, the teacher must be trained and prepared to teach job risk prevention in the classroom and propose procedures that allow the development, application and updating of a prevention culture from a position of flexibility and continuous improvement (89.1% with a mean of 3.21).

Another fundamental axis in the teaching-learning process is the student. The teachers’ opinions point out the importance of this process from a significant and quality perspective (active learning), where students become involved in their own training. They understand that activity, exploration and investigation are important mechanisms in the educational-prevention process (91.9% and with a non-significant response dispersion level of 0.570, indicating the homogeneity of the response to this statement). In other words, the teachers must start with previous experiences that have emerged from the students in order to determine the level of instruction in this area (83.1%, with a mean value of 3.18).

In the school, it is also important to highlight the school leadership team, which is perceived by the teachers as fundamental in supporting initiatives and lines of action, such as fomenting the awareness and involvement of all the personnel in health and safety topics in the school, facilitating adequate means and installations to better carry out the activities. In this way, steps are taken to revise and improve the effectiveness of prevention in their school and encourage creativity and innovation in prevention topics (94.1%, with a response value of 3.34 and an absolute response homogeneity of 0.531).

Regarding the most suitable educational levels to teach prevention, the majority of the teachers (85.7% with a mean of 3.77) consider that the instruction should focus mainly on secondary education. Thus, the educational level that obtains the greatest consensus and unanimity is vocational education (84.9% with a mean of 3.32), followed by compulsory secondary education (82.3% with a mean of 3.12), and finally upper secondary (78.3% with a mean of 2.91). It should be kept in mind that more than half of the teachers also think this instruction should be provided in primary school (63.2% with a mean of 2.34).

With regard to the contents, the teachers state that prevention should be taught in a transversal way (89.9%, with a mean of 3.22) in the different traditional subjects, and that the public administration should foster prevention from this perspective (90.3% with a mean of 3.54).

Regarding the teaching of prevention from the different educational levels, the teachers state that prevention should be taught through the subjects of technology and physical education and in subjects within the sciences and social sciences (88.7% with a mean of 3.32).

The teaching of prevention must be approached by focusing on the students, taking into account their interests, motivations, etc. (88.4%, with a mean of 3.25), and the contents must be taught cyclically in the cycles/stages, in order to increase the level of knowledge (86%, with a mean of 3.1). These contents must be the same ones dealt with in the job world (80.1%, with a mean of 2.95). For example, the contents to be taught must revolve around concepts such as “preventing injuries” (96.2% and with a mean of 3.53), “being trapped or stuck”, “blows” and “falls”; “intoxication due to inhalation”, “ingestion or skin contact with toxic products”; “physical and psychological overload” and “fires and explosions”, “burns and electrocution”. These contents have consolidated percentage values ranging from 90.7% to 86.8%, with a high response value corresponding to a mean of between 3.41 and 3.30.

Regarding the way prevention should be taught in the school context, the teachers agree that the best methodology must focus on getting the students (capabilities, attitudes, etc.) to become responsible for their own actions; it must be based on a holistic (globalized) and social interpretation of prevention (90.3% with a mean of 3.56), thus rejecting prevention instruction designed in terms of “process-product”, quantifying the time employed, accountability, etc. (89.5% with a mean of 1.56) (traditional and positivistic perspective of education).

To achieve full efficacy in teaching prevention, the teachers consider that the main element is the activity, defined as a procedure that transforms the theory into elements of practical application. Thus, they coincide in pointing out that in designing an activity, it is important to emphasize the idea of prevention, safety, health, respect, awareness, consciousness, etc. (83.5% with a mean of 3.13%). Moreover, these activities must foster the participation of the family (91% with a mean of 3.45).

Resources are another aspect to highlight in teaching prevention. The teachers advocate audiovisual media through DVDs, cinema, television, video, etc. (94.3% with a mean of 3.6), and computer and technological resources, such as the Internet, multimedia software, interactive CDs, etc. (90% with a mean of 3.3).

With respect to job risk prevention planning, the perfect strategy is the School’s Educational Project (87.5% with a mean of 3.12). It must contemplate the prevention needs and expectations stemming from the work reality and, thus, establish priorities to satisfy the needs and expectations that arise. In order for prevention to be synonymous with consensus and unanimity in the schools, it is fundamental to foment participation. For the teachers, it is extremely important for the Education and Employment Administration to establish a line of mutual collaboration, support and guidance in all its actions (93.4% with a mean of 3.35).

It is important to highlight that the lack of human and material resources, the inexistence of stimuli, financing and support from the administration, the need for considerable time to do the activities, and excessive class size are factors that the teachers feel should be taken into account in the development and initiation of prevention initiatives (95.3% with a mean of 3.65).

The teachers state that to achieve an evaluation of the prevention culture and be able plan prevention projects in the school, it is important to evaluate the procedures used in the classroom, the means and/or resources based on criteria of quality, quantity, use and interest, and the level of acceptance of the content by the students, parents and teachers (93.4% with a mean of 3.47).

Regarding the contingencies analysis, the main conclusions we extracted about the independent variables –highlighting the significant relationship with each of them-, are the following:

1. The male teachers over 41 years old think it is quite important to foment the students’ participation in doing prevention activities.

2. The teachers between 31-40 years old, with experience ranging between 11 and 20 years, state that it is quite important for the teacher-classroom teacher to be familiar with the reality of the job world the students will be entering.

3. The teachers over 41 years old highlight the need for the administration to promote job risk prevention as a subject to be taught.

4. The teachers over 41 years old, and with experience ranging between 21 and 30 years, think it is quite important for the prevention content to be taught from a perspective focused on the student, and that the activities should be designed in a comprehensive way, taking into account their interests and motivations.

5. The primary school teachers think it is quite important for the prevention activities to exemplify, as much as possible, the prevention learning context we want to transmit, based on students’ everyday situations, without omitting the basic prevention concepts (safety, health, etc.).

6. The teachers who hold the position of School Head say it is quite important for the teacher to be the facilitator of the prevention culture in the classroom, and he/she must be trained and prepared to do so.

7. The teachers who hold the position of head of studies think it is quite important for the teacher to previously diagnose the instructional needs of their students in terms of prevention.

8. The teachers who perform the job of “support teacher” think that one of the training contents for the students should be intoxication by inhalation, ingestion or skin contact with toxic products, and that the activities should be based on the students’ own experiences.

9. The teachers who are heads of studies think that the optimal resources for teaching prevention are audio-visual media such as digital cinema, television, video, DVD, etc., as these resources would help to achieve a prevention culture to a greater degree.

10. The teachers mentioned above also coincide in pointing out that it is quite important to organise joint activities with other schools in matters of prevention, and that this work should be done by the School Leadership Team.

11. These same teachers state that one of the main obstacles to teaching prevention in the classroom is the lack of support and encouragement by the administration.

12. The teachers with teaching experience that ranges between 21 and 30 years consider it quite important that one of the contents to be taught be related to students’ auditory problems due to noise abuse.

13. The teachers who work in Pre-primary Education consider it quite important for the students to learn prevention at the Vocational Education levels because the prevention contents must be the same as the ones they will need in the labour world.

14. The General Education teachers indicate that it is quite important to carry out institutional campaigns to promote prevention in schools as a resource in the compulsory levels of the educational system.

15. The Technology teachers believe strongly in the need to promote a continuous “flow of communication” in order to efficaciously manage prevention in the school.

Components and characteristics of the training to prepare institutions

Objective 3

In the entire prevention training process, it is necessary to know the components and characteristics of the instruction in this subject. Thus, the teachers state that instruction by the classroom teacher, with the help of an external specialist agent in prevention, is the best way to teach prevention (94.2% with a mean of 3.33). When it is not possible to have an external agent to complete the teaching of prevention, it is necessary for the teacher-classroom teacher to be properly trained (80.1% with a mean of 2.96). For this purpose, various topics are mentioned: safety, hygiene, ergonomics and psycho-sociology, strategies for the transversal nature of the prevention culture, and strategies to manage prevention in the school in the case of belonging to the school leadership team (84.7% with a mean of 3.02).

Teacher training, whether initial or continuing professional development, will have to respond to a series of conditions. Regarding Initial Teacher Training, the best formulas for consolidating and fostering prevention stem from the acquisition of prevention contents through the observation of the world of work, along with a close relationship between the theoretical contents and “laboratory practice” (82.4% with a mean of 3). Finally, regarding continuing professional development, the teachers think the most attractive formulas are the training and orientation activities offered by the CEPs (Teacher Training Centres) (87.5% with a mean of 3.16), as well as the model where the school is understood as on-the-job training; that is, the training stems from experience and contact with the labour reality emerging from the socio-personal context (75.7% with a mean of 2.87).

In this dimension, the most important conclusions extracted from the contingencies analysis related to the variables –highlighting the significant association with each of them-, are the following:

1. The teachers over 41 years old think it is quite important to train the teaching staff in strategies and instruments that address prevention management in the school.

2. The teachers from 31 to 40 years old think it is quite important for teacher training in prevention to integrate strategies for developing the transversal nature of the prevention culture.

3. The male teachers, along with teachers from the departments of physical education and languages, think it is quite important for the students’ prevention training to be carried out by the classroom teacher, along with an external specialist agent in prevention with a basically technical background.

4. The teachers with accumulated experience of more than 41 years consider it quite important for the teacher training to address the psycho-sociology of the teacher and the student. This topic must emphasise contents related to stress, mobbing, “burn out” or professional exhaustion, etc.

5. The teachers who belong to the mathematics department feel that it is quite important for continuing professional training in prevention to be developed through training and orientation activities offered by the CEPs (Teacher Training Centres).

DISCUSSION OF RESULTS: IMPROVEMENT PROPOSALS AND/OR STRATEGIES DIRECTED TOWARD TEACHERS

The proposals extracted from this study are directed toward improvement and quality in promoting a job risk prevention culture, basically focusing on the teachers. The teachers must adopt the role of “facilitator”, be committed to knowledge and the transmission of prevention values, and awaken the students’ interest in contents and activities related to health and safety, coinciding with Nielsen (2004) and Burgos-Garcia (2013).

Also, the author agrees with Burgos-Garcia (2013) when teachers must teach job risk prevention in the classroom by proposing procedures that allow the development, application and updating of the prevention culture from a divergent and holistic perspective.

Another improvement proposal is to programme the prevention training activities by taking the student into account. This implies adapting the actions to the needs, interests and developmental level of the students, as presented by Weare and Markham (2005).

It is important to adopt a transversal teaching methodology focused on the student, as indicated by Young (2014), based on their interests and motivations, in the different traditional subjects, in order to efficaciously work on job risk prevention in the classroom, specifically in subjects like technology, physical education and those included in the sciences and social sciences.

The teaching of prevention must be approached in a cyclical way in the different cycles/stages, in order to progressively increase the knowledge about prevention, which is the same as in the labour world.

Moreover, organising the instruction around contents such as: “preventing injuries”, “being trapped or stuck”, “blows” and “falls”; “auditory problems due to noise abuse”; intoxication by inhalation” “ingestion or skin contact with toxic products”; “physical and psychological overload” and “fires and explosions”, “burns and electrocution”, “stress”, “mobbing”, “burn out or professional exhaustion”, is related to what is manifested in the First Andalusian Plan for Occupational Health and Job Risk Prevention for teachers in public schools dependent on the Department of Education (2010-2014).

The teacher’s task must be to educate the students in an environment rich in multi-disciplinary experiences and practices that interest them, as pointed out by Rivara (2001) and Burgos-Garcia (2013), across various subjects and with teachers participating from different areas to achieve a global and comprehensive approach.

Teachers must design activities using audio-visual resources, through DVDs, cinema, television, video, etc., and computer or technological resources, such as the Internet, multimedia software, interactive CDs, etc.

Finally, we also coincide with the European Safety and Health Agency (OSHA, 2012) in highlighting an improvement proposal, where teachers, in order to achieve quality education in terms of prevention, safety and health, must receive preparation in their Initial Training and later in the Teacher Centres. They must be able to evaluate the teaching-learning methodology used, the suitability of what is taught for the objective proposed, and the media and/or resources based on criteria of quality, quantity, use or interest in the classroom.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Azeredo R, Stephens-Stidham S (2003). Design and implementation of injury prevention curricula for elementary schools: lessons learned. Injury Prevention (9):274-278. |

|

|

|

|

|

Burgos-Garcia A (2013). Success factors in teaching occupational risk prevention in schools: Contributions based on teachers' experience in Andalusia (Spain). Br. J. Educ. Soc. Behav. Sci. 3(4):359-381. |

|

|

|

|

|

Cea MA (2001). Metodología cuantitativa: estrategias y técnicas de investigación social. Madrid: Síntesis. |

|

|

|

|

|

Cohen L, Manion L (2007) (6th edition). Research methods in education. London: Routledge. |

|

|

|

|

|

Council of Ministers (Spain). (2007). Strategy for Occupational Safety and Health (2007-2012). Madrid: Ministry of Employment and Labour. |

|

|

|

|

|

Employment Council of the Regional Government of Andalusia (Spain). (2010). Second Andalusian Plan for Occupational Health and Job Risk Prevention for teachers in public schools dependent on the Education Department of the Regional Government of Andalusia (Spain) (2010-2014). Seville: Directorate General of Occupational Health and Safety. |

|

|

|

|

|

Fox D (1987). El proceso de investigación en educación. Pamplona: EUNSA. |

|

|

|

|

|

Gil-Flores J (2003). La estadística en la investigación educativa. Revista de Investigación Educativa 1:(21):231-248. |

|

|

|

|

|

Hofmann RJ (2010). Complexity and Simplicity as Objective Indices Descriptive of Factor Solutions. Multivariate Behav. Res. 13(2):247-250. (Published online: 10 jun 2010). |

|

|

|

|

|

Jansen B (2012). How to adapt to the changes in society and in the world of work: a new community health and safety strategy (2000-2004 y 2004-2008 and 2008-2012). Luxemburg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. |

|

|

|

|

|

Lizosoain L, Joaristi L (2003). Gestión y análisis de datos con SPSS (version 11.0). Madrid: Thomson-Paraninfo. |

|

|

|

|

|

Lohr Sh L (2000). Muestreo: dise-o y análisis. México: International Thomson Editores. |

|

|

|

|

|

McMillan JH, Schumacher S (2006) (6th edition). Research in Education: Evidence-Based Inquiry. New York: Allyn & Bacon and Pearson Education. |

|

|

|

|

|

Miller TR, Romano EO, Spice RS (2002). The teaching of safety and health in the educational centers. Future children (10-1):137-163. |

|

|

|

|

|

Morales-Vallejo P, Urosa-Sanz B, Blanco-Blanco A (2003). Construcción de escalas de actitudes tipo Likert. Madrid: La Muralla. |

|

|

|

|

|

Nielsen P (2004). What makes community-based injury prevention work?. In search of evidence of effectiveness. Injury Prevention (10):268-274. |

|

|

|

|

|

Occupational Safety and Health Agency (OSHA). (2004). Rome Declaration on Mainstreaming OSH into Education and Training. Roma: OSHA. |

|

|

|

|

|

Occupational Safety and Health Agency (OSHA). (2012) (3th edition). Mainstreaming occupational safety and health into education: good practice in school and vocational education. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. |

|

|

|

|

|

Rivara FP (2001). Injury Prevention. A guide to Educative Research and Program Evaluation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

|

|

|

|

|

Weare K, Markham W (2005). What do we know about promoting mental health through schools?. Promotion Educ. (12):3-4. |

|

|

|

|

|

Young I (2014). (5th edition). Health promotion in schools: Promotion and education. Paris: IUHPE. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0