This study had attempted to investigate assessment practices and factors for grade 8 students score disparity in Regional versus Teacher-made exams, from 2015 in Bench Maji Zone primary schools. In doing so, a descriptive survey method was employed. A sample of 185 stakeholders composed of 58 teachers, 101 students, 14 principals, 11 Woreda Education Department Officers, 12 school supervisors and the Zone Education Bureau Officer participated. Purposive sampling technique was employed to identify the participating individuals. As tools of data collection, questionnaire, semi-structured interview, and document review were employed. The collected data were analyzed qualitatively as well as employing percentage correlation in accordance to the thematic areas, primarily to substantiate the quantitative descriptions. The results with respect to assessment had shown that teachers were applying the traditional pyramid of assessment procedures whereby the proportion of assessment of learning (Summative Assessment) dominates assessment as learning and assessment for learning which are vital for better learning and performance. The correlation between students' scores in Regional versus Teacher-made exams was found to be positive but very much lower than the absolute positive correlation coefficient value (ɤ=0.476**at p<0.01 level of significance). The contributing factors for the existing score disparity were the traditional assessment practice itself, assessment feedback provision experiences, differences in invigilation room setting and degree of control, and large class size. Also included are commitment differences among students themselves, differences in the difficulty and quality standard of exam questions, poor study skills, support provision variations obtained from parents, supervisors, principals, Education office and Education department officers. Therefore, concerned stakeholders must cooperate fully and responsively to put in place proper assessment which contributes much for effective learning.

Assessment plays an important role in the process of ensuring the quality of the overall educational process of any nation. It provides the necessary feedback required in order to maximize the outcomes of educational efforts.

As described by Airasian (1991), continuous formative assessment is considered as an assessment approach which should depict the full range of sources and methods teachers use to gather, interpret and synthesize information about learners; information that is used to help teachers understand their learners, plan and monitor instruction and establish a viable classroom culture. As pointed out by Cone and Foster (1991), good measurement resulting in accurate data is the foundation for sound decision-making. The assessment of students' learning provides objective evidence necessary in the decision-making process in education. There is little doubt among educational practitioners about the special value of assessment as a basic condition for effective learning. However, there has been an increasing criticism in the educational field of high stakes formal examinations of having harmful effect on students' learning and that it should be reduced to a minimum (Harlem and Crick, 2003; Morrison and Tang, 2002; Black, 1998).

Research supports that attention to assessment for learning improves students’ achievement. Black and Wiliam (1998), indicated that formative assessment, if properly implemented in schools, is a powerful means to improve student learning. To this, a research conducted by Olufemi (2014), showed that there is a significant relationship between the junior secondary school continuous assessment scores (JSSCAS) and the overall performance in junior secondary school certificate examination in mathematics (JSSOT). Moreover, Black and Wiliam (1998) found that students taught by teachers who used assessment for learning would achieve in six or seven months what would otherwise take a year.

In order for assessment to play its important roles, Baker and Stites (1991) on their part suggested that continuous assessment should involve a formal assessment of learners' affective characteristics and motivation, in which they will need to demonstrate their commitment to tasks over time, their work-force readiness and their competence in team or group performance contexts. In line with this, the Ethiopian educational reforms have led to the introduction of continuous assessment to our curriculum to offer teachers the opportunity to make stronger links between teaching, learning and assessment. However, for continuous assessment to be used effectively, teachers must be willing to confront a number of obstacles when changing to a system of true formative assessment. When the educational system is evaluated, assessment has traditionally been linked with formal exams particularly promotion and school-leaving end of year exams.

In connection to balancing teacher-student participation, Clark and Starr (1986) noted the rate of retention of pupils as: "pupils generally remember: 10% of what they read, 20% of what they hear, 30% of what they see, 50% of what they hear and see, 70% of what they say, and 90% of what they say as they do a thing." They added that, valid evaluations depend on accurate measurements and assessments. Consequently, evaluation of students' progress must be a two-step process. In the first step, one must gather the pertinent data for an assessment of students' status. For this purpose, assessors employ tools and techniques to estimate both the quality and quantity of students' learning. The second step is to use the information to make reasoned judgments concerning the merits and inadequacies of students and programs in light of the instructional objectives.

The ultimate purpose of teaching is to bring about learning (required competences) in students. This students' achievement is usually expressed in terms of numerical scores and practical aspects too. Learning is with no doubt continuous and that better learning requires active engagement of learners in varied and meaningful learning experiences throughout the teaching-learning process. In line with this, Black and Wiliam in Hanover Research, (2014) which compiled over 250 publications indicate that students who receive formative assessment perform better on a variety of achievement indicators than their peers who do not receive. Some researchers like Alonge (2004), Cliff and Imre (1981), and Thorndike and Hagen (1977), observed that teacher-made tests in general are quite defective evaluation devices. The common faults put forward by these researchers include not covering the range of objectives specified by the teacher in terms of contents and educational objectives, ambiguity of question items and test characteristics that are inappropriate for the purpose for which the teacher wants to use the test results.

The intention behind introducing continuous assessment in the instructional and testing process is to achieve two major purposes: to improve both the validity and reliability of the results of pupils' performance on tests and exercises, and to help learners develop effective learning and work habits. Besides, formative assessment requires continual follow up and provision of constructive feedback from the side of the assessor/s. When this lacks, the progresses made by each learner and the challenges faced are not going to well known and remediation and enrichment will be questioned. However, from the researchers’ personal observations, the present practices researchers’ personal observations, the present practices towards implementing continuous formative assessment in Bench Maji Zone seemed essentially based on frequent test taking which does not really serve the two critical purposes of continuous assessment. Moreover, there is a tendency to conceive assessment as a separated process from the teaching-learning process. Again, it seemed yet customary that the provision of immediate feedback and comprehensibility of exams are lacking.

Therefore, the researchers decided to carry out this research for the reasons that poor attention has been given for students support, particularly in terms of continuous formative assessment with proper feedback. Therefore, this survey study stressed on addressing the herein basic research questions:

i. What are those teacher-student related factors that negatively affect the academic achievement of grade 8 students in Regional exams?

ii. How do teachers prepare grade 8 students for Regional exam from the affective learning perspective?

iii. How do teachers practice assessment during teaching and learning from the perspectives of nature of continuity, variety and immediacy and degree of constructiveness of feedback?

iv. Is there considerable achievement difference between students of Governmental and Private schools?

Objectives of the Study

Generally, this study was aimed at investigating assessment practices and corresponding teacher-student related factors that contribute for disparity between students’ academic scores in teacher made and Regional exams. Specifically, the study aims at:

i. Identifying teacher-student related factors that affect grade 8 students’ academic scores in regional versus teacher-made model exams,

ii. Identifying teachers' experiences to realize emotional readiness of grade 8 students for regional exams,

iii. Identifying assessment strategies that teachers are accustomed to apply during teaching and learning,

iv. Identifying students’ academic score gaps between Governmental and Private Schools and the contributing factors.

Significance of the Study

The study is expected to have the following benefits and beneficiaries:

i. Firstly, the study may guide teachers to work for the betterment of their assessment practices.

ii. Secondly, it arouses learners’ interest to work hand-in-hand with teachers to improve their academic achievement in both classroom and Regional exams.

iii. Thirdly, it can serve the school leadership of the study area, in their effort to counter the identified challenges.

iv. Fourthly, it can serve as an input for Zonal Education Office and Woreda Education Departments to adjust their support in-line with the scholarly recommended principles.

v. Finally, this study may serve as a baseline for all interested individuals to study the issue in detailed and wider scope.

Proportion of students who pass and fail

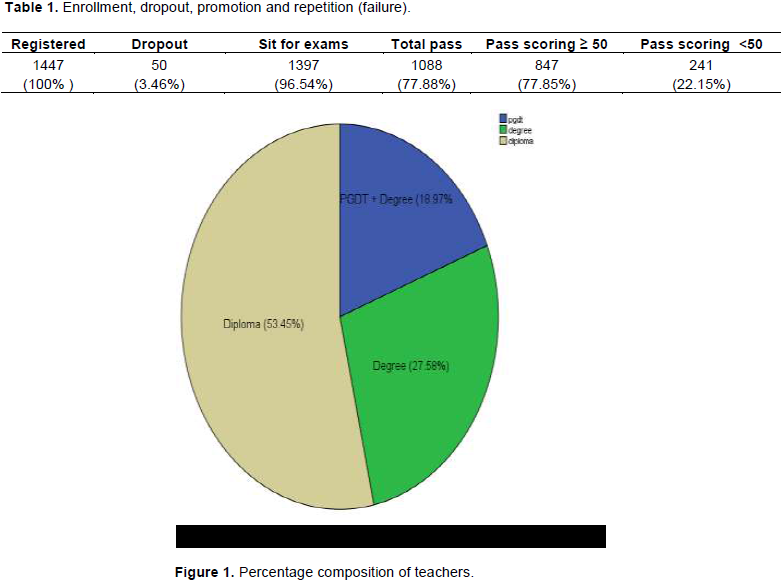

The data with respect to grade eight students of the 14 sample schools in Regional Exams as obtained from the Zonal Education Office is summarized and presented in Table 1.

Table 1 shows the number of total enrollment, dropping out, students who sit for exams, and pass and fail. In relation to pass or fail in Regional Exams, 100% of students of the three privately owned schools and five governmental schools namely Abuneteklehaymanot, Misgana, Zemedeab, Gedu, Otuwa, Shey Bench, Jemu and Kasha pass the Regional Exam. While all private and some governmental school students totaled 847 (77.85%), pass scoring ≥ 50; there are yet significant number of students (241 which comprise 22.15%) enrolled in some governmental schools who pass scoring below an average mark of 50 which is less than the minimum standard endorsed in the 1994 New Education and Training Policy of Ethiopia. Students who pass scoring below the minimum standard was by far significant in governmental primary schools such as Bajeka (76.74%), Teramaj (75%), Aman (70%), Anjo (68.18%), Jeba (41.03%), Maji (34.33%), Jemu (27.78%), and Shey Bench (11.83%). Whereas, Otuwa, Kasha, and Gedu contributed 0.99, 1.98, and 2.68% respectively.

Failure is the other area of concern of the background data. It is highly pronounced in Teramaj (87.88%), followed by Aman (59.89%), Bajeka (55.20%), Jeba (22.22%), Anjo (12%) and Maji(9.45%). Like that of private academies, five governmental schools, namely Jemu, Gedu, Otuwa, Shey Bench, and Kasha, registered no failure Appendix I.

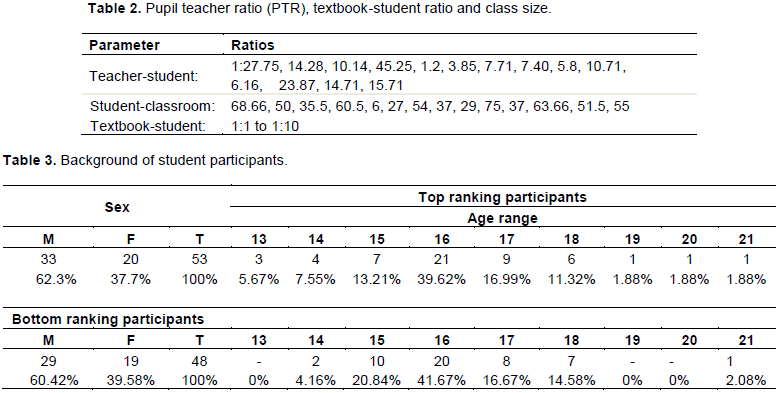

Composition of participant teachers by qualifications

Figure 1 shows that a large proportion of teachers, 53.45% were diploma holders followed by degree holders who constituted 27.58% of the participants and 18.97% of the teachers who possessed degree plus PGDT (Post Graduate Diploma for Teachers) certificate. It should be noted that teachers who participated in the study were teachers teaching at grade eight. According to the New Education and Training Policy of Ethiopia (MoE, 1994), the minimum required qualification to teach at this level of schooling is Diploma in Education or teaching. The data in Figure 1 reveals that while majority (53.45%) of teachers in the study had the minimum qualification level of requirement to teach second cycle primary school students, the remaining 46.55% of teachers surpassed the minimum qualification requirement by holding degree and degree plus PGDT certification.

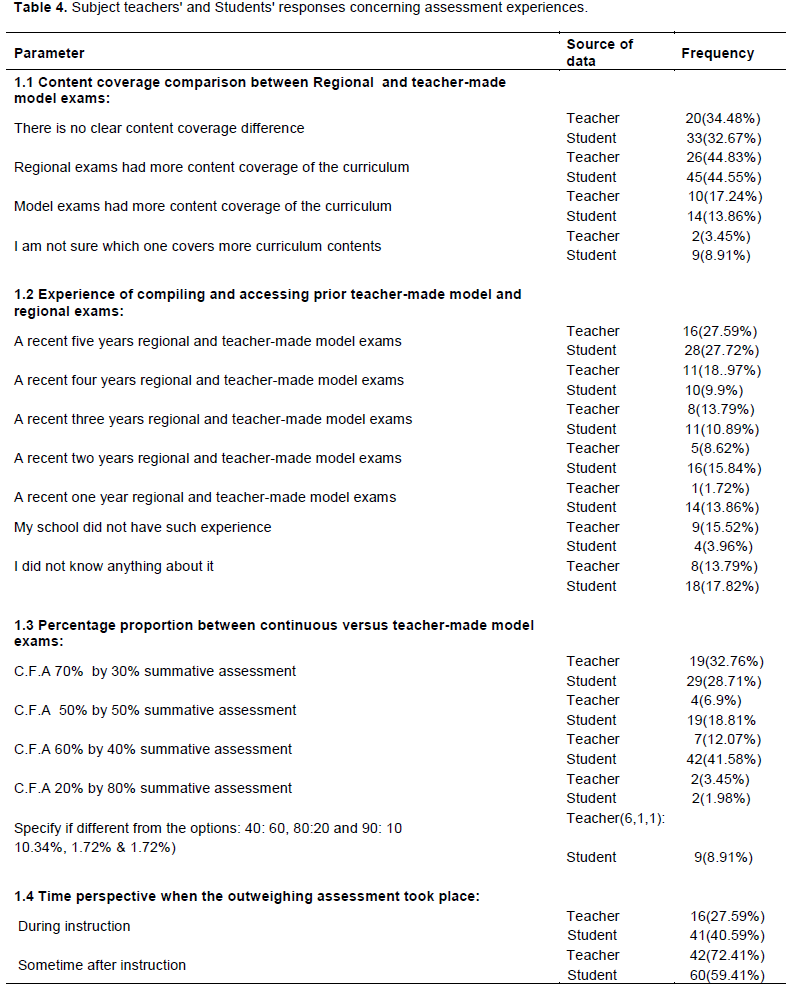

According to Ronald et al. (2006), the calculation of pupil/teacher ratio and class size is quite different. While pupil/teacher ratio is a global measure of the human resources brought to bear, directly or indirectly on children's learning, class size refers to the actual number of pupil taught by a teacher at a particular time. Thus, pupil/teacher ratio is always lower than the average class size. Consequently, while pupil/teacher ratio is very important from administrative and economic viewpoint, what matters from psychological viewpoint, in terms of how students learn, is the number of students who are physically present interacting among themselves and with the teachers.

Note that the issue of PTR and class size appropriateness in the sample schools of this research is compared and contrasted in line with scholarly recommended figures. According to research findings obtained from a study conducted upon 766 lower primary schools of Northeast Karnatanka by Azimir Premji Foundation (2006), a PTR of less than 30:1 has a high correlation with superior school performance. Again, the Right to Education Act (Article 26 of UNESCO, 1960) mandates a pupil to teacher ratio of 30:1 in order to ensure that children learn better in the classroom. Schools in which the PTR was between 10 and 20 showed the best learning levels as a result of convenience to participate all in all matters of schooling, manageability to conduct variety of assessment tools and provision of on time feedback and easing the burden of the teacher to know each learner in detail. The Azimir Premji Foundation (2006) investigation on the other hand evidenced that pupil teacher ratio less than 10:1 results in poor academic performance, which possibly arises from insufficient peer interactions that backfires through making the classroom instruction boring. Thus, the ideal PTR according to AzimirPremji Foundation (2006) study is found to be somewhere between 20:1 and 25:1.

According to some scholars, the impact of PTR differs across level of schooling. In this connection, a research conducted by Esther and Haroon (2014), envisaged that a higher pupil teacher ratio exceeding 18 has a larger negative effect on the likelihood of attaining a primary education than that of a higher education and the effect is get worse with an increase in pupil teacher ratio. This is because primary school students are more reliant upon teachers than high school and tertiary level students are.

As have been shown in Table 2 of this study, the PTR in the 14 sample primary schools of Bench Maji Zone at grade 8th by 2015 averagely ranges from 45.25:1 of Aman Primary School to 5.8:1 of Anjo Primary school in case of Governmental Schools and 10.14:1, 3.85:1 and 1.2:1 at Misgana, Abune teklehaymanot and Zemedeab Academies respectively. Aman Primary school with a PTR (45.25:1) and that of Otuwa General Primary School with PTR (27.75:1) were found to exceed the higher limit of the ideal PTR, which is 20:1 to 25:1 of Azimir Premji Foundation (2006) and from what is recommended by Esther and Haroon (2014). Again, PTR of Zemedeab Academy (1.2:1), Abuneteklehaymanot (3.87:1), Jeba Primary School (7.51:1), Jemu Primary School (7.40:1), Anjo Primary School (5.8:1), Teramaji Primary School (6.16:1) were found less than PTR of 10:1 which is not recommended by some scholars such as Azimir Premji Foundation (2006).

From Table 2 PTR data of this study, one can infer that it is the size of the total enrollment of grade eight students determines PTR in Primary Schools of Bench Maji Zone than the academic principle. Moreover, the interview data obtained from principals evidenced that the increase in the proportion of PTR in the 11 governmental schools was partly contributed by the assignment of teachers to teach more than one subject including subjects out of their actual area of study. Such a teachers' assignment experience to teach out of their specialization is thought significantly damaging to the quality of instruction and the ultimate outcome, which is students' competence.

It is a fact that there is no consensus with regard to the number of students for small and large classes. For instance, for Butler et al. (2001), McKeachie (2002), Yoder and Hochevar (2005) and Laura et al. (2015), classes with 15 to 30 are small and > 30 students are large. For Daniel and Rosenberg (1998) and Sarah (2006) small classes are those containing 13-17 and large classes containing 22-25 students respectively; to Finn and Achilles (1990) and Ronald et al. (2006) small class size is a maximum of 20 students per classroom. When the reference point is the suggestions of these scholars, the case of Bench Maji Zone schools at grade 8 was found large enough out of the fourteen sample Primary Schools.

Thus, Maji with 75 students per classroom, Otuwa with 68.66 students per classroom, Shey Bench with 63.66 students per classroom, Aman with 60.5 students per classroom, Gedu with 55 students per classroom, Jeba with 54 students per classroom, Kasha with 51.5 students per classroom, Bajeka with 50 students per classroom, Jemu and Teramaji with 37 students per classroom, and Misgana with 35.5 students per classroom fall under large classes. From the eleven Primary Schools with large class sizes, seven of them had even more than the maximum class size endorsed in the 1994 New Education and Training Policy of Ethiopia. On the contrary, Anjo with 29 students per classroom, Abune teklehaymanot with 27 students per classroom and Zemedeab with 6 students per classroom fall under small classes. Likewise that of PTR, class size was found to be determined by total student enrollment than the scientific principles.

Even though it requires further in depth comparative study, as have been argued by many scholars, while 11(78.57%) of the schools with large classes disadvantaged their students, the rest 3 (21.43%) schools are thought securing the benefits of small class sizes. Laura et al., (2015) on their part noted that the size of the class might affect students' ability to learn. Small class size encourage increased student-teacher interaction; it allows thorough evaluation of students' learning; and it permits greater teaching flexibility (Eugene and Linda, 1997). Students in large classes have less one-on-one time with the teacher, they are suffocated, there is disciplinary problems, which leads to less instructional time and in turn lower test scores. Whereas in smaller classes, students are given more instructional time, they feel comfortable and are able to focus more on the curriculum being taught instead of maintaining discipline and other issues, which affect and destroy their attention span (Sarah, 2006) and overall students' performance. Valuation is more negative in large class sizes (Bedard and Kuhn, 2008), and small class size favors active learning that helps to maximize students' level of understanding or capability to retain what have been taught more effectively (Butler et al., 2001; McKeachie, 2002; Yoder and Hochevar, 2005; Laura et al., 2015).

The data in Table 2 moreover shows that textbook-student ratio lays between 1:1 and 1:10 ranges. The ratios 1:2 to 1:10 is believed to significantly decrease the chance of students to make use of the textbooks for doing home works and studying purposes. Material (textbook) shortages in the 21st century are beyond what one can expect and is believed to negatively affect students' overall learning and self-assessment engagements. Private schools in particular reported that concerned offices did not fairly distribute teachers' guides and textbooks though they paid the cost. For this reason, private schools were forced to buy from bookstores in the market incurring additional budget. The lack of teaching materials (teachers' guide, textbooks and references) is yet a common serious problem in governmental schools as well, but no way to buy and cover the gaps.

As had been shown in Table 3, top 5 and bottom 5 ranking students of the 14 sample schools totaled 140 participated in this study; but only 101 (72.14%) had been engaged during the actual data gathering time. This had happened because the rest 39 (27.85%) of the sampled students were transferred to other Zones and Woredas situated out of the geographical scope of the study.

According to the Ethiopian New Education and Training Policy (MoE, 1994), the official primary school entrance age in Ethiopia is 7 years old. However, it was found that late entrants comprise the greater proportion than the normal age entrants do. Accordingly, while the proportion of age 14 and 13 (normal and early age entrants) comprised of 8.91%, those with age 15 to 21 who are late entrants comprise 91.09% of the participating students. Among the late entrant student participants, age 16 encompassed 39.62 and 41.67% of top 5 and bottom 5 ranking students respectively. Accommodating late, very late, normal age and early age entrants in same classroom is a very challenging task to all teachers; particularly to less experienced ones.

Assessment practices of grade eight teachers

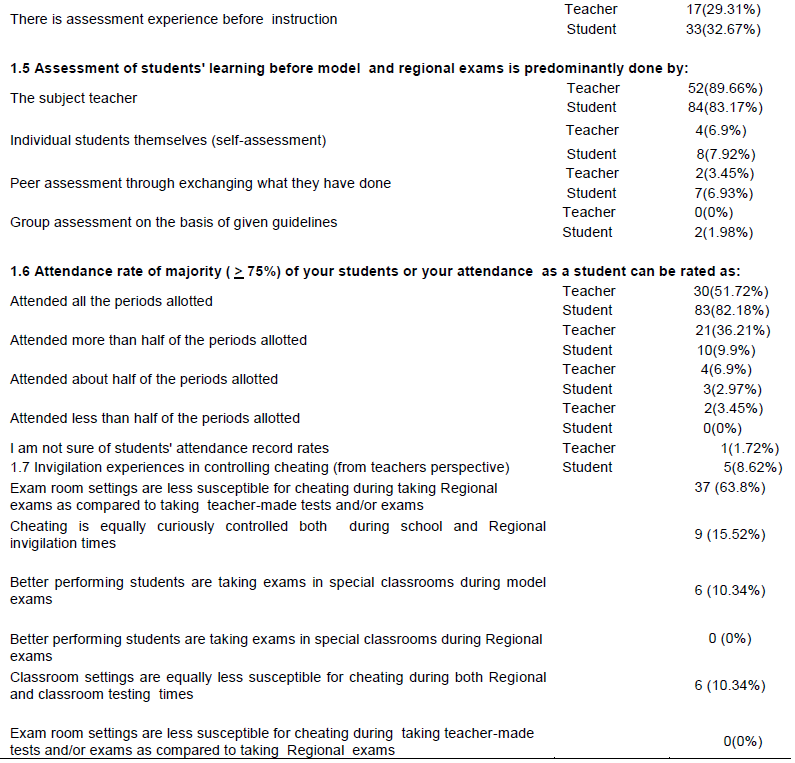

As an element of the learning-teaching process, the way subject teachers are assessing students' learning progresses plays its part in determining academic scores and/or successes. In order to investigate how grade eight teachers were practicing assessment, 58 teachers were asked to indicate their actual practices. For triangulation purpose, top five and bottom five ranking students of the 14 sample schools planned to fill the same questionnaire. Out of 140 planned sample participants, 101 participated. This had happened because 39 students had left their prior places of residence by the 2015 academic calendar to places far away from the geographic scope of the research. Thus, the analysis and interpretation was done based on the data obtained from 72.14% of students as indicated in Table 4.

Table 4 holds seven questions having alternatives to make answering at ease. The questions are adopted from literature to be used for identifying assessment practices in relation to the teaching-learning process. While six of the questions were presented to 101 students and 58 teachers, the seventh one was presented to teacher samples as it dealt about teachers' role during invigilation.

Accordingly, the data with respect to item 1.1 that is, content and/or objective coverage comparison between Regional and Teacher-made Model exams depict Regional exams outsmart in content and/or objective coverage. To express in numerical terms, 26 (44.83%) teachers and 45 (44.53%) students noted that Regional exams had more content coverage of the curriculum than Teacher-made Model exams. Yet, numerically second ranking proportion of sample teachers and students that is 20 (34.48%) and 33(32.67%) respectively argued as there was no such noticeable content coverage difference between the two exams. Again, though the number of respondents is not significant, there were 2 (3.45%) teachers and 9 (8.91%) students who replied as they are not sure about which exam had more content overages. This finding largely coincides and to a lesser degree contradicts with the suggestions of Alonge (2004), Cliff and Imre (1981), and Thorndike and Hagen (1977).

Item 1.2 of Table 4 was about the experiences of sample schools concerning compiling and accessing previous Regional and Teacher-made Model exam sheets for preparing their students. Accordingly, 16 (27.59%) teachers and 28 (27.72%) students replied five years; 11 (18.97%) teachers and 10 (9.9%) students reported four years; 8 (13.79%) teachers and 11 (10.89%) students reported three years; 5 (8.62%) teachers and 16 (15.84%) students replied two years; and 1 (1.72%) teacher and 14 (13.86%) students replied one year. Again, 9 (15.52%) teachers and 4 (3.96%) students replied as their schools did not have any experience of compiling and accessing Regional and Teacher-made Model exam sheets.

This data was obtained from sample respondents from schools, whereby the 2015 grade-8 graduates were first batch to them. Yet, 8 (13,79%) teachers and 18 (17.82%) students replied as they did not have any knowledge about the matter related to compiling and accessing exam sheets. These samples were found to be having no or less care and concern about their respective roles. For triangulation purpose, 14 school principals were interviewed about the experience of compiling and accessing previous Regional and Teacher-made Model Exam Sheets to students. Data showed that, 3 (21.43%) replied as their school had experience of compiling and accessing (some even through borrowing from sister schools) but, failed to specify the count of accessed Model and Regional exams by year. Whereas, nearly half of the principals, 6 (42.86%), replied as if their schools had no experience. From those who specify the count of years, 2 (15.38%) replied as their students were accessed a recent five years Regional and Teacher-made Model Exam Sheets, and as to the other 2 (15.38%) their students were accessed exam sheets of recent three years and 1 (7.69%) principal replied as they did accessed a recent seven years exam sheets. Inconsistencies had been found among the data obtained from teachers, students and principals.

Item 1.3 of Table 4 deals with the percentage proportion of continuous summative assessment versus Model exam in sample schools. In this respect, while majority of teachers, 32.76%, replied 70:30 proportion, majority of students, which comprise 41.58%, replied the 60:40 proportion, which contradicts one another. From teachers side, there were 7(12.07%) who reported the 60:40 proportion. Still, significant number of students, which is 29 (28.72%), replied the 70:30 proportion. Moreover, 4(6.9%) teachers and 19(18.81%) students replied the 50:50 alternative, 2 (3.45%) teachers and 2(1.98%) students replied the 20:80 percentage proportion. On the other hand, the remaining sample teachers and students specified other proportions than given ones in the questionnaire. Accordingly, 6 (10.34%) teachers gave 40:60; 1(1.72%) teacher, 80:20; and again 1(1.72%) teacher noted 90:10 proportions respectively. Among student samples, 9(8.91%) students replied as there exist different proportion of assessment than given ones, without specifying the percentage. In essence, it had evidenced that there were inconsistencies across schools and subjects, as exact sameness was not expected. There were experiences in private schools in particular to undertake more than 100% assessment records and conversion of it back to the standard maximum evaluation proportion had been undertaken. The finding predominantly coincides with the suggestions of MoE (2013).

Item 1.4 in Table 4 was about the time perspective when the outweighing assessment took place. The data obtained from 58 teachers and 101 students had shown that the greater portion of assessment had taken place after instruction took place sometime in the past than during instruction. To specify it, while 42(72.41%) teachers and 60(59.41%) students replied the out-weighing assessment portion took place after instruction, 16(27.59%) teachers and 41(40.59%) students argued that the outweighing assessment took place during instruction. For the twining question under item 1.4 of Table 4 asking whether or not there is assessment practice before instruction, 17(29.31%) teachers and 33(32.67%) students replied that assessment still took place before instruction which is a good start to implement modern assessment. As a continuation of item 1.4 of Table 4, which was used to identify the outweighing percentage of assessment employed across the three periods of assessment (i.e. Before Instruction, During Instruction and After Instruction), one open-ended question was presented to teacher samples. The concern of this question was identifying assessment tools they used during the three periods when assessment was recommended. The finding witnessed that; the assessment practice was highly inclined to summative form of assessment, which contradicts with the data for item 1.3, and suggestions of MoE (2013) and Dorothy (2012).

Assessment tools used before instruction

In relation to such period of assessment, the data obtained from 58 teachers revealed that they were unaware of the essence of "Assessment before instruction." For this, 48 teachers mentioned oral questions in relation to the new lesson topic (brainstorming questions), questioning and answering about the previous lesson, pair work, correcting homework, and class work that are inappropriate. This had disproved what 17 (29.31%) teachers and 33(32.67%) students replied, as there exist experience of using assessment before instruction. This period of assessment usually took place during the first meeting with students for the primary purpose of knowing students background knowledge and to act the way it can match. The rest 4 teachers omit the item and the other six had given fully unrelated note, which witnessed that grade 8 teachers are unaware of such assessment experience. In general, it seemed that, the whole teachers were getting confused between the activities of the deductive element "introduction" and “assessment before instruction".

Assessment tools during instruction

Unlike the previous first period of assessment, teachers in this period of assessment were found to have clear understanding evidenced by the data obtained from 54(93.10%) teacher participants. They listed the tools of assessment they make use of during instruction which are: oral questions to check students attention level and degree of their learning, class work, quiz, pair and/or small discussion followed by reflection. Also included is the revision questions concerning the new lesson for stabilization purpose, which goes with the suggestions of Thomas and Vincent (2001), Maddalena (2005) and Black and Wiliam (2014). Yet, while 3 teachers omit the item, 1 teacher replied he has never used assessment tools thinking it aroused classroom disturbance which witnessed their misconception, because no literature supports formative assessment as a cause for disciplinary problems.

Assessment tools used after instruction

As literatures support (Harlem and Crick, 2003; Broadfoot, 2001; SQA, 2015; Morrison and Tang, 2002), the primary purpose of this period of assessment and the tools employed is summative one. In this period of assessment, 46(79.31%) teachers mentioned the right tools like homework, test, assignment, worksheets, model exams, and doing previous model and regional exam sheets. Nevertheless, still there were 4 teachers who omit the item and 8 teachers who noted tools inappropriate for this period of assessment such as: quiz, class work, and oral questions which had assured the failure to differentiate the time perspective of assessment and the right tools to be employed.

Item 1.5 in Table 4 was concerned about who predominantly assesses students' learning excluding model and Regional exams. The alternatives were the subject teacher, self-assessment, and group assessment. Among 58 teachers and 101 students who participated, 52 (89.66%) teachers and 84 (88.17%) students replied that the subject teacher is responsible; 4 (6.9%) teachers and 8 (7.92%) students replied students' self-assessment; 2 (3.45%) teachers and 7 (6.93%) students replied as peer assessment was dominantly employed and no teacher and 2 (1.98%) students confirmed that group assessment had dominated. From this, it can be understood that self, peer and group assessments were not noticeably practiced at grade-8 which contradicts the scholarly recommendations made by Thomas and Vincent (2001), Maddalena (2005), Dorothy (2012) and Black and Wiliam (2014).

Item 1.6 in Table 4 was demanding data about the rate of attendance of majority (≥75%) of students during the 2015 academic year. Accordingly, 30 (51.72%) teachers and 83 (82.18%) students replied that they attended all the periods; 21 (36.21%) teachers and 10 (9.9%) students replied they attended more than half of the periods. Also, 4 (6.9%) teachers and 3 (2.97%) students attended about half of the periods; 2(3.45%) teachers and no student attended less than half of the periods, and 1(1.72%) teacher and 5(8.62%) students are not sure about the rate of attendance. It evidences that; there is a need to improve rate of attendance on one hand and build responsiveness on the side of those who are not sure of their peers and students rate of attendance. This partly goes in line with 80% and above rate of attendance requirement and partly in different with the recommendation of MoE (2013).

Item 1.7 in Table 4 was presented to teacher samples only which dealt about the invigilation experience of teachers in controlling exam cheating. From 58 teachers who participated, two alternatives from the six: "better performing students seat for exams in special/separate/ classrooms during Regional exams" and "exam room settings are less susceptible for cheating during taking Teacher-made tests and/or exams as compared to taking Regional exams" attracted no teacher respondent. While 6 (10.34%) teachers replied that, "Better performing students took exams in separate setting/exam rooms/ during Model-exams, just equal number of teachers argued "Classroom settings are equally less susceptible for exam cheating during both exam times." 9 (15.52%) teachers on their part replied "Exam cheating is equally curiously controlled both during school and Regional invigilation times." However, the majority of teachers comprised of 37(63.8%) noted that; "Exam room settings are less susceptible for cheating during Regional exams as compared to the setting during Teacher-made tests and exams." The finding is to a lesser degree consistent with the suggestions of Qualifications and Curriculum Development Agency (2010), Elinazi (2014), and Joanne (2017).

Types of assessment tools frequently used

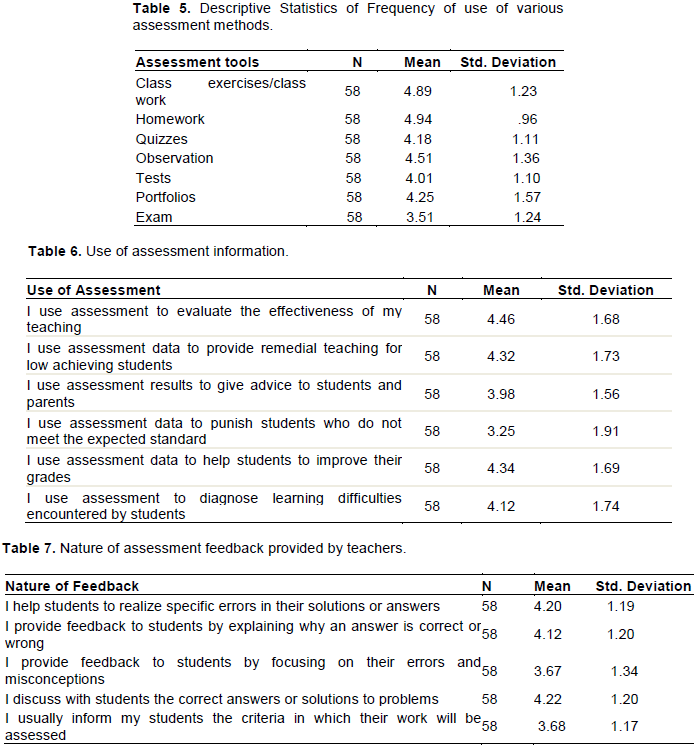

Teachers were asked to indicate the frequency in which they make use of it. Accordingly, they were made to use a scale in which 1 - Never, 2- Once a year, 3- Once a term, 4 – monthly, 5 – weekly and 6 – reflected daily use. Responses provided by teacher respondents are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5 shows that the most frequently used assessment tools include homework, class work, observation, portfolios quizzes and tests in a decreasing rank order. Exam was the least frequently used tool of assessment followed by test, which coincides with the suggestions of educational measurement and evaluation principles, as they are mostly used for summative purpose. This finding coincides with Joyce (2013).

How do teachers use assessment information?

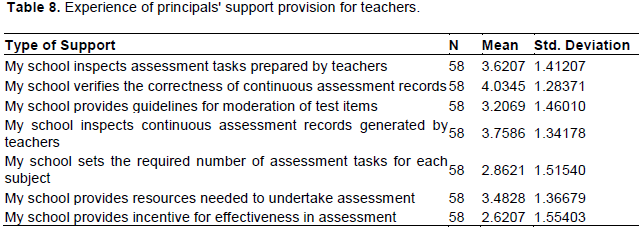

In an attempt to explore the predominant purpose to which assessment information was used, various possible uses of assessment information were given and teacher respondents were asked to indicate the frequency of their actual practice. Results obtained are presented in Table 6.

Responses of the teachers presented in Table 6 indicates that the most predominant uses of assessment were in "evaluating the effectiveness of their teaching, helping students to improve their academic score, providing remedial teaching for low achieving students and diagnosis of learning difficulties" at mean= 4.46, S.D= 1.68, mean= 4.34, S.D= 1.69, Mean= 4.32, S.D= 1.73, and mean= 4.12, S.D= 1.74, respectively. The use of assessment in "providing advice to students and parents" with (mean= 3.98, S.D = 1.56) and the item "I use assessment information to punish students who do not meet required standard" (mean= 3.25, S.D= 1.91) are found less frequently used ones than others. Though the use of assessment to punish students who do not meet expected standards does have negative effect on students' motivation, yet some teachers make use of it. Such practice of teachers is not scholarly advisable. Instead, they should give appropriate instruction to raise their achievement standards. It coincides with the findings of Joyce (2013).

Assessment feedback provided by teachers

In an attempt to explore the nature of feedback provision of primary school teachers and the frequency in which such feedback is rendered, they were asked to use a 5-scale in which; 1 reflected never, 2- rarely, 3- sometimes, 4- often, and 5- very often. Responses obtained are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7 shows the nature of feedback mostly provided to students and emphasizes on correcting their work. The items " I discuss the correct answers or solutions to problems with students" (mean= 4.22, S.D = 1.20),"I help students to realize specific errors in their solutions or answers" (mean= 4.20, S.D= 1.19), and "I provide feedback to students by explaining why an answer is correct or wrong" (mean= 4.12, S.D= 1.20) had been found to be the most frequently used natures of feedback provisions. This evidenced that teachers devote most of their time in correcting students' work and provision of frequent feedback. The items " I provide feedback to students by focusing on their errors and misconceptions" and "I usually inform my students the criteria in which their work will be assessed" with (mean= 3.67, S.D= 1.34; and mean= 3.68, S.D= 1.17) respectively were found to be the less frequently used natures of feedback provisions. This implies that there are some teachers who gave lesser emphasis on appreciating the positive dimensions of students' performances on one hand and not doing well in communicating the criteria they use in assessing students' work on the other hand. Thus, it is advisable for teachers to give due emphasis for both strong and weak sides in their feedback provision and yet should strengthen their communication with students on the criteria they use to assess; so that students become aware of it and strive to achieve desirable learning outcomes. The findings in most areas go in line with Joyce (2013).

Support provision to teachers in improving formative assessment practices

As an aspect of continuing professional development indorsed into the schooling system in Ethiopia, the need to provide professional support is unquestionable. The need to introduce modern way of formative assessment as an important aspect of instructional process is necessary to do task for better learning. Among the bodies responsible to discharge such a support are school principals, school supervisors, Zone Education Office and Woreda Education Departments. In order to disclose what had been done to replace the traditional pyramid of assessment by the modern one, open-ended questions were included in the questionnaire presented to teachers. Moreover, cluster supervisors, Officer of the Zone Education Bureau, and Officer of Woreda Education Department were interviewed.

Support rendered by principals

According to the data obtained from respective principals of: Misgana and Abuneteklehaymanot Academies, and Aman, Gedu, Anjo, Shey Bench and Maji primary schools, annual assessment schedules and/or guidelines have been developed, ratified and communicated to all teachers. Progresses in relation to the implementation of assessment plan has been checked and analyzed at department level to take corrective measures. In Abune teklehaymanot Academy, if a student scored ≤7 marks out of 10 points assessment task, the score had been considered as failure and tutorial class ranging 1:30-2:30 hours has been offered for improvement. Moreover, weekly Question and Answer forum was undertaking in the Academy. In Shey Bench Primary School, the proportion of continuous summative assessment and summative assessment was set to be 100:30 to 140:30 and communicated to subject teachers. In addition, within two weeks range each month, the school had general evaluation forum with students, and teachers primarily focusing on continuous assessment implementation progresses and challenges encountered. The experience in Maji Primary School was giving test after each two weeks lesson in all subjects, then score analysis had been done followed by setting actions to be taken. Aman Primary School in its part had emphasized on making use of variety of formative assessment tools. Likewise, the principal of Gedu Primary School had experience of determining the type and number of tools of assessment, communicated to teachers and implementation has been properly monitored.

On the other hand, the provision of training in relation to formative assessment had been given due emphasis in: Abuneteklehaymanot, Misgana and Zemedeab academies, by invited guests, Anjo, Teramaji, Jemu, Jeba, Bajeka and Otuwa Primary schools, by the principals themselves. More specifically, Teramaji primary school had rendered training, with regard to the proper utilization of continuous assessment twice a year for all teachers in general and for newly recruited ones in particular. Moreover, it was requested that all teachers to plan continuous assessment implementation strategies in accordance with the three domains of instructional objectives and then, the administrative body had supervised whether or not they put in place. Again, teachers' peer observation took place and feedback had been given for further betterment. The principal of Bajeka Primary School in his part had dispatched an assessment manual obtained from U.S AID and arranged experience sharing program between novice and experienced teaching staff. Whether or not this qualitative data coincides with the quantitative data concerned the researchers and took further steps. The support provisions coincide with MoE (2013) suggestions.

What kind of support does School provide in implementing classroom assessment?

The study intended to explore the kind of school support that teachers receive in conducting classroom assessment. They were given statements reflecting possible kinds of support from school with a 5-point scale indicating the frequency whereby; 1-never, 2-rarely, 3-sometimes, 4-often, and 5-very often. The mean of teachers' responses related to the frequency in which each support provided are presented in Table 8.

The mean results in Table 8 reveals that the support teachers received from principals was low in most aspects except the item "my school verifies the correctness of continuous assessment records" with (mean=4.03, S.D= 1.28). While the two items "My school provides incentives for effectiveness in assessment" with (mean=2.62, S.D- 1.55) and "My school sets the required number of assessment tasks for each subject" with (mean=2.86, S.D= 1.51) had revealed very low emphasis; the rest of the items: "My school provides guidelines for moderation of test items" (mean=3.20, S.D= 1.46), "My school provides resources needed to undertake assessment" (mean=3.48, S.D=1.36), "My school inspects assessment tasks prepared by teachers" (mean=3.62, S.D=1.41), and " My school inspects continuous assessment records generated by teachers" (mean=3.75, S.D= 1.34) had been given moderately low concern in schools. Thus, the support rendered by school principals in the process of implementing effective classroom assessment seemed poor. From this, it is possible to say that the school principals tend to take for granted that each teacher is responsible for conducting classroom assessment at the expected standard as to their belief. The findings are inconsistent with the suggestions of MoE (2013) and the findings of Joyce (2013).

Support from cluster supervisors

Both governmental and private schools were clustered and supervisors had been assigned to each cluster. Their primary role has been undertaking close supervision and rendering professional support for better instruction. According to school principals and cluster supervisors, the support rendered was fully discriminatory whereby private academies namely: Abune teklehaymanot, Misgana and Zemedeab were not served at all but, Maji, Jemu, Jeba, Teramaji, Shey Bench, Bajeka, Aman, Kasha, Gedu, Anjo and Otuwa had gotten noticeable support. Unlike the other two private academies, Misganaacademy had employed their own full time supervisor to undertake closer supervision and render support in all aspects of instruction, which include assessment. For crosschecking purpose, cluster supervisors were interviewed about the efforts they make to help teachers with regard to undertaking continuous formative assessment. According to the 14 cluster supervisors, they had undertaken classroom observations upon the overall standard of the instructional process and rendered face-to-face feedback on both strengths and weak areas for improvement. As an important aspect of instruction, assessment experiences of teachers were given due emphasis. In addition, they disclosed that their support varies from school to school because of distance from the place of dwelling of the supervisor. Again, one cluster supervisor assured that private academies were not as such equally served, which coincides with the argument of private academies. These private academies are located in the Zone capital, Mizan-Aman Town Administration, and were clustered together with government schools. Except the partiality, it goes with what MoE (1994) and MoE (2013) suggested.

Support rendered by Zone Education Office and Woreda Education Departments

School principals were interviewed about the support rendered by the two offices towards maximizing promotion rate of grade-8 students. According to the data obtained, principals held two different stands: as they had gotten considerable support and did not gotten significant support. This might partly arise from the difference in their expectation. Principals of Misgana, Abuneteklehaymanot, Zemedeab, Maji, Bajeeka, Jeba and Aman argued that as they had received nothing from both the Zonal Education Office, Woreda Education Department except distributing registration formats and answer sheets-to help students get familiar with it, and arranging experience sharing tour following its overall performance evaluation of schools at Woreda level (in government schools). The Principal of Aman added that the Woreda Education Department forwarded repetitive non-constructive criticism and degrade the effort of the school rather than provide support. Private schools in particular even failed to get textbooks and teachers' guides for the past three years, even though they paid the required amount of money.

On the contrary, Principals of Jemu, Teramaji, Shey Bench, Kasha, Gedu, Anjo and Otuwa Primary schools noted as that they had gotten significant level of support to raise the rate of students' promotion. Textbook and Teacher's Guides distribution was done by the coordinated efforts of the Zone Education Office and Woreda Education Department and provided trainings upon maintaining educational quality and minimizing educational wastage. Moreover, the Regional Education Bureau in collaboration with the Zone Education Office provided training on how to promote Early Grade Reading Ability (EGRA)-to avoid poor background. Of course, the support given in case of Gedu General Primary School was request based. As to the principal of Teramaji, Zone and Woreda level plans in relation to avoiding academic wastage meaning; making dropping out and failure rates to become zero; will be sent to the school and the school acted accordingly. The principals of Shey Bench, Gedu, Anjo and Otuwa noted that, the Zone Education Office had distributed enough number of teacher's guide and textbooks on time except that of the two subjects: English and Amharic. Again, the Zone had initiated the preparation of Model exams by instructors of Mizan-Tepi University, and the Woreda Education Department played the facilitation role during exam sheet distribution and invigilation. However, both the Zone and Woreda level professionals arranged no training opportunities. According to the principal of Kasha, experts from the Zone and Woreda had given awareness creation orientation towards the consequences of exam cheating and its future impacts and on other misconducts as well. The support rendered by Zonal and Woreda level experts in general evidenced partiality in Bench Maji Zone; whereby noticeable supports were not rendered in seven schools and had been given in the rest seven schools as to MoE (2013).

Score disparity of students in: model versus regional exams

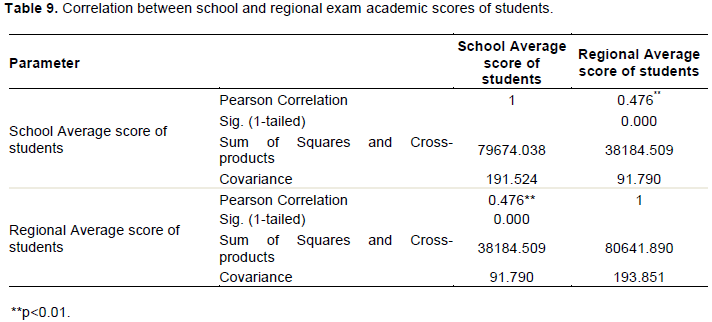

Academic score of a student may vary across tests or exams because of variety of contributing factors. In this research, overall average score of students registered in Teacher-made model exams was compared against their corresponding overall average score registered in Regional exams to examine whether or not there is an increase-increase, increase-decrease or no relationship.

The correlation coefficient value in Table 9 shows that there is positive relationship between average academic scores of students at Regional versus Teacher-made model exams (r= 0.476**; p=0.01). This indicated better performance in Teacher made model exams is preceded by better performance in Regional exams or low performance in Teacher-made model exams is also an indicator of low performance in Regional exams. Yet, because the correlation coefficient value (0.476 < 0.5) the relationship between the average scores of students in the two exams can be labeled having moderate correlation.

Although not the only factor, the way teachers prepare their students to sit for exams is believed to influence students' academic score and actual performance in real life situations. A "yes" or "no" questionnaire was presented to teacher samples in order to explore the how they prepare students for exams. The questionnaire embraced four close-ended and three open-ended questions.

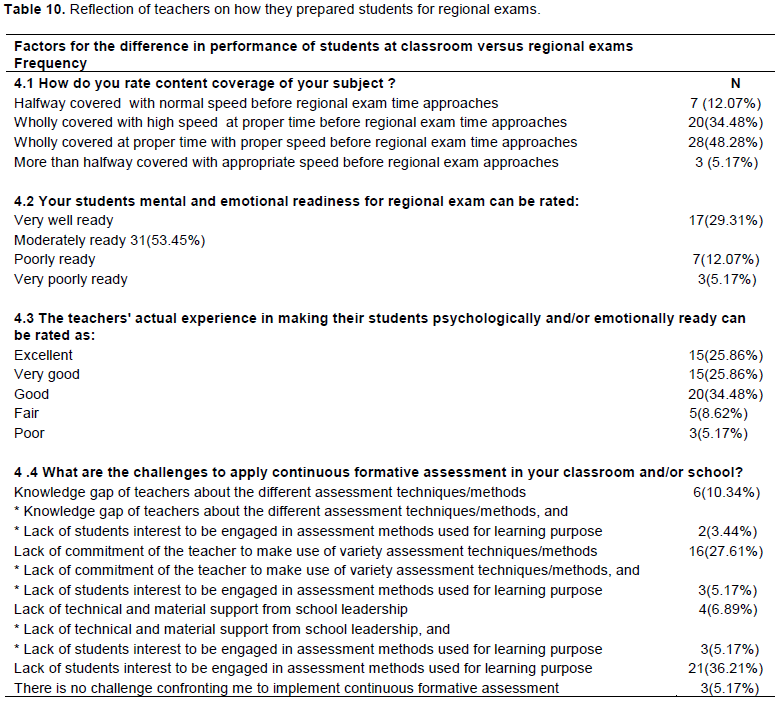

Item 4.1 of Table 10 requested teachers to rate how much of the syllabus contents of grade-8 were covered before the Regional exam time since 2015. The item had four alternatives and 28(48.28%) teachers replied as they had covered "whole contents of the subject at a proper time with proper speed before the Regional exam time". Numerically second ranking proportion of teachers, which was 20 (34.48%), had replied as they had "fully covered contents of the subject they had taught with high speed than normal before the Regional exam time." While 7 (12.07%) replied as they "covered halfway of contents with normal speed ahead of Regional exam time," 3(5.17%) disclosed as they had "more than halfway covered with appropriate speed before Regional exam time."

Item 4.2 in Table 10 was requesting teachers to rate how they view the students' status of mental and emotional readiness to sit for Regional exams. From the alternatives given, 31(53.45%) teachers viewed their students' readiness "moderately ready," 17(29.31%) labeled "very well ready," 7(12.07%) rated "poorly ready," and 3(5.17%) on their part argued that the students were "very poorly ready." Item 4.3 in Table 5 as continuation of Item 4.2 was about the efforts made by teachers in order to ensure their students psychological and emotional readiness for Regional exam. From the quality indicators of teachers' effort 20(34.48%) replied "good", while 15(25.86%) labeled their effort "excellent", the other 15(25.86%) labeled their effort "very good". Yet, there were 8 teachers out of which 5(8.62%) teachers disclosed their effort "faire" and 3(5.17%) teachers who replied "poor" respectively. From this, it can be generalized that majority of teachers did labeled their students readiness "moderate" and the effort they made "good."

Item 4.4 in Table 10 was used to identify the challenges, teachers faced in attempting to apply continuous formative assessment in their instructional engagement. As the data in Table 10 show, while some teachers identified single factors, some others provided a combination of factors having equivalent weight. The first ranking factor, which challenged teachers to make use of continuous assessment for formative purpose, was "lack of interest/willingness from students’ side to be engaged in assessment activities for non-summative purpose." 21 (36.21%) teacher respondents had identified this factor. The second ranking contributing factor was found to be "lack of teachers' commitment to make use of variety of methods/techniques of assessment for formative purpose" as had been identified by 16 (27.61%) of teachers. Thirdly, as to the other 6 teachers which comprised of 10.34% "knowledge gap of teachers with regard to the variety of formative assessment techniques/methods" was responsible. From a group of teachers who identified single challenging factor, 4 (6.89%) of them replied "lack of technical and material support from the school leadership" and 3 (5.17%) noted "there were no challenges they encountered while making use of continuous formative assessment." The second category of teachers argued that the challenge to implement continuous formative assessment had resulted from the combination of two factors having equivalent contribution. Accordingly, to 3(5.17%) teachers, the challenges were "lack of teachers commitment and lack of students interest to be engaged in non-summative assessment". The other 3 (5.17%) noted that "lack of technical and material support from the school leadership, and lack of students' interest to be engaged in non-summative assessment activities" and as to the rest 2(3.44%) teachers, "knowledge gap of teachers about different techniques/methods of assessment, and lack of students' interest" in combination were the significant challenges.

As an extension of the close-ended questions of Table 10, which gave clue about the contributing factors for students' score disparity in Regional versus Teacher-made Model Exams, three open-ended questions were presented to teachers to let them freely express their thought.

Amongst the three open-ended questions, item 4.5 requested teachers about what did they do to help students to be wholehearted and ensure emotional readiness to sit for Regional Exams. Accordingly, 50 (86.21%) teachers noted as they had provided academic advice and support as an important tool to build the "I can do spirit" in each student. The specific areas of academic advice can be sub-divided into two: academic advice in relation to preparation and academic advice in relation to countering back challenges faced during exam. From the aspect of making students well prepared, repetitive testing and ensuring they have sufficient knowledge on a subject matter and scheduling all aspects of their day-to-day life with greater emphasis on their study were mentioned. Also worthy of mentioning are helping them to place emphasis on "learning to know than learning to pass exams," letting students to engage in doing questions collected from Regional Exams of different years following completing each unit of the subject, provision of guidance and counseling services to boost both mental and psychological/emotional/ readiness. Also, making them do previous Regional and Teacher-made Model exams individually within the time budget specified to make them time conscious and self-reliant as well as in groups to let them learn one from the other; undertaking marking and scoring of the two exams and provide feedback as there exists no significant difficulty level difference between the two exams, which help them to lessen and/or avoid exam anxiety. In addition, letting them take care of Regional exams as there is a probability of failure and helping them experience how to provide answers through shading given "Os" were mentioned. The rest 8 (13.79%) noted their usual duty; which ensured, they missed the essence of the question.

In an extended investigation, with regard to students' level of confidence during the exam times, an open-ended question of comparison was presented to 101 student participants. The data obtained revealed as 41(40.60%) students were fully equally self-confident in cases of both exams, 23(22.77%) ones were having low level of self-confidence, 19(18.81%) had better self-confidence during Teacher-made Model Exam time and 7(6.93%) had better self-confidence during Regional Exam time. There were yet 11(10.89%) students who omit responding to the question.

As to the rationale behind the respective levels of self-confidence, those 41 fully and equally confident ones during both exams notified; as it had resulted from being well prepared ahead of time, get ensured by their day-to-day performance, and the teachers and school administrations were rendering high status support the whole academic year. On the other hand, those 23 students whose level of confidence was low in both exams forwarded: as they lacked preparation resulting from being poor in their prior academic background; lack of study skills (poor study habits); work overburdening at home (for self-supporting and rural dwelling students). Lost of concentration (for students at towns), whereby their attention was distorted by TV programs and play stations were also included. For the 19 students, who had better self-confidence during Model Exams, the contributing factors were: they had known how the subject teacher sets questions, it did not result in failure, content coverage was well communicated and the invigilators were not strange people. Whereas, 7 student participants argued that they were rather had better self-confidence during taking Regional exams. This was so because items were found clearly stated emphasizing on major concepts and ideas and understanding than very specific unnoticeable concepts in need of dry memorization. In addition, there were items in Model exams, which are long, unclear and add some hesitation as if you were unprepared or less prepared and unfit for the level.

With regard to the academic advice and support rendered to students in relation to avoiding challenging situations during Regional Exams, experience sharing prior to exam time in relation to what should they do in cases of confronting with questions they are not sure of the answer and on how to change the given answers when needed. Also letting them leave their worries about the exams primarily taken aside and concentrate on the upcoming exams in a relaxed mood had been mentioned.

In relation to ensuring students readiness to sit wholeheartedly during Regional exams, the interview data obtained from principals of sample schools depicted similar actions to what had been mentioned by teacher samples. Of course, the intensity and type of support rendered varies in some ways from school to school. To this, while Abune teklehaymanot Academy made use of "four round model exam provisions", Misgana Academy had employed a kind of forum named "Tea Program" and Teramaji Primary School was running "Discussion Forum" on monthly basis whereby, teachers and students took part. Whereas, Gedu Primary School had rendered "tests which composed of 40 questions each week."

In general, since the data in Table 5 with regard to teachers' view towards the status of students' mental and emotional readiness was found 'moderate' and the efforts they made 'good' as to 31(53.45%) and 20(34.48%) of teachers respectively. Also, because only 41(40.60%) students replied they were 'fully equally confident' during both exam times, what teachers and principals forwarded about the support rendered to ensure mental and emotional readiness are liable to be questioned and/or evidenced the existed significant variations among schools in this aspect.

Guidance and counseling provisions

The provision of such services is believed to have paramount importance in preparing students for Regional exams. In this connection, principals of the 14 sample schools were interviewed "whether or not they had an office and personnel assigned for the provision of guidance and counseling services and the issues addressed." The interview data had evidenced that there are 8 schools (governmental ones) which had no experience at all. However, the rest 6 schools had experiences in the provision of guidance and counseling services. Amongst these six schools, two private academies were having B.A degree professional in Psychology rendering the services of which one was part timer and the other one was fulltime employees. In the rest four schools: Civic and Ethical Education teacher at one school, all subject teachers, the unit leader and the principal in coordination, in the second school, Civic and Ethical Education teacher and the Females' club in the third school, and model and more experienced teachers in the fourth school had handled guidance and counseling service provisions. In general, guidance and counseling services were found rudimentary and less organized when compared to the standards of MoE (1994).

In schools where there exist office and personnel, the most important issues of students addressed by schools are: developing self-confidence, finding own potentialities, falling in sight love, consecutive disruptive behavioral characteristics, guilt feelings in relation to bodily changes and experiencing incidental menarche, sexual harassment related depression, exam anxiety, withstanding sex drives affecting learning and the likes.

The second open-ended question, item 4.6 as part of Table 5, was aiming at identifying the possible teacher related, students' own, parent related, and school related factors contributing to score disparity in Regional versus Teacher-made Model Exams. The question was having the premise "students achieve better average score in Model Exams as compared to Regional Exams."

Teacher related factors

In relation to this factor, 11 (84.62%) of private and 10 (22.22%) of governmental schoolteachers rejected the premise and argued that the students instead score better in Regional Exams. They had justified that their students were passing through by doing more challenging model exams and thus it is easier for them to do the less challenging Regional exams on one hand and there are times when students lacked concentration during seating for Model exams because it did not result in failure. Even though unlawful, there are data evidences in that; some students missed Model exams.

In contrary to this argument, 2(15.38%) of private and 35(77.78%) of government school teachers agreed as their students score better average score in Model exams in support of the premise. They believed that, the disparity in students score at teacher-made model versus Regional exams was registered because of the following reasons:

One of the most frequently mentioned factor was related to teachers' professional competence expressed in terms of lack of experience in teaching grade-8 level, poor qualification from the aspects of instruction and subject matter knowledge gaps, teaching subjects other than their area of study. In addition, commitment, which is lesser than expected, exhibited in poor subject matter content coverage, and provision of biased attention to better performing students and leaving aside the rest. The second equivalently mentioned factor, which teachers believed contributing for score disparity was related to lesser difficulty level of model exam questions. In specific terms, the questions in model exams as compared to questions in Regional exams were simple to do, promote learning through memorization, less inclusive in content cover an

From the findings and discussions, the following conclusions can be made in relation to assessment practices and rationales behind the comparative score disparity in Regional versus Teacher made exams:

I. The minimum average score to promote from one grade level to the next level is expected to have a standard set in the curriculum of a country. Consequently, the Ethiopian Education and Training policy of 1994 endorsed an average mark of 50 to be the minimum requirement. However, average score of 40 marks was applied by 2015 at grade eight, which is indifferent from what the policy says. Such act of violating own promotion policy seemed an attempt to compromise quality of education. There is a year-after-year inconsistency about the lower average cut point to promote from grade eight to ninth grade. By 2015 the promotion rule violation had saved 241 (22.12%) grade eight students from so called "academic wastage" which is numerically less significant as compared to those majority students who pass scoring 50 and above average marks.

II. From the aspect of promotion rate comparison made between private and government schools, private ones outperform by registering 100% promotion record year after year even by scoring greater than an average mark of 50 as compared to a few government schools having registered 100% promotion. Such noticeable gap results from the quality differences in the process of preparing students for life and education. Private ones implement scheduled study hours after class, establish teacher-student friendly relationships, and communicate with parents in case students score poorly during continuous assessment. This might partly be as their earning will only be sustainable if and only if their academic services are fit for the demands of their students as well as students' parents.

III. Schools are expected in whatever ways to work hard in order to access students with previous exam sheets for preparation purpose. Thus, the experience of schools with respect to compiling and accessing previous regional and model exam sheets was among areas of emphasis in this study. The actual task accomplishment of schools was found very well in schools having grade eight graduates before 2015. Students in these schools were accessed at least either a single year exam sheets of all subjects to a recent five years. Whereas, those schools, which did not have graduated batches before 2015, were not having the initiation to borrow from sister schools and make accessible.

IV. Findings on the influential factors, PTR and class size, were found to be done haphazardly, which was fully liable for the number of student enrollment than coinciding with what literature suggested (Azim Premji Foundation, 2006; Laura et al., 2015; Sarah, 2006; Jeremy and Charles, 1999).

V. Support provision expected to be rendered by school principals to promote proper utilization of continuous formative assessment and assessment as learning was found to some degrees in the right track in all private academies and a few government schools. Yet, it seemed done for formality (report purposes) in most government schools. Those that were in the right track had the experience of developing detailed assessment procedures and requirements followed by continual systemic follow up whether or not the plan was put in place and undertake evaluation forums with students and teachers as well as with parents in some instances. More importantly, they rendered training about promoting continuous formative assessment and assessment as learning. Whereas, a majority of government schools, an overall plan of assessment had been communicated to teachers for implementation. The next steps such as undertaking follow up for gap identification, provisions of on time feedback, and attempting to solve the challenges/gaps was almost non-existence. In general, though there is little strive to apply continuous assessment for learning, the general scheme of assessment can be labeled traditional one whereby, assessment of learning outsmarts the proportions of assessment for learning plus assessment as learning.

VI. On the other hand, support provisions from cluster school supervisors, Zone Education Office and Woreda Education Departments was found to be discriminator and very much limited to instructional material distribution, budget allocation to government schools and collecting list of students for statistical purposes. The support given from cluster supervisors was also limited to government schools leaving aside private ones and still less intense in schools situated far away from the residential place of supervisors. Again, though what they actually done was largely limited to material and financial support provisions, the Zone and Woreda Education Offices were established to pursue technical and professional supports as well. As to the data obtained from private academies, Zone and Woreda education officers except taking list of students gave no technical support. Moreover, enough instructional materials were not distributed for private schools as per their demand though they paid for books and teachers' guides. Therefore, support provision in promoting better assessment for learning scheme remains a big assignment.

VII. The instructional less syllabus content coverage, which by implication limit content and/or objective coverage in model exams make students less competent in doing regional exams. Moreover, the speedy mode of delivering lessons just for finishing contents had negative effect on students’ learning. This experience implies that, teachers did have incompetence in the proper planning as well as pursuing what they planned.

VIII. From the findings in Tables 6 and 7 which dealt about the "experiences of teachers in the use of assessment information" and the "nature of assessment feedback provided by teachers" it is possible to conclude that schools were in a promising position in most areas. A six scale and six items questionnaire in the case of 'teachers' experience in the use of assessment information' and a five scale and five items questionnaire in the case of 'nature of assessment feedback provided by teachers' were used. Mean values ranging from (mean= 3.25;S.D= 1.91 to mean= 4.46; S.D= 1.68 and mean= 3.67; S.D= 1.34 to mean= 4.22; S.D= 1.20) had been obtained.

The findings evidenced that the concept 'Assessment for learning' is not well understood by school principals, v/principals, teachers, supervisors and even by Zone and Woreda level officials who had direct role assignments with the issue. It has been misconceived as 'continuous summative assessment'. Therefore, the Zone Education Bureau in collaboration with professionals from nearby Teacher Training Colleges and Universities should run a well-structured CPD plan to address the huge gaps identified through long-term trainings.

Gap identification and provision of constructive feedback are among the functions of assessment for learning to be promoted. Therefore, schools should implement scheduled weekly consultation and feedback sessions with students to be run by subject teachers whereby both positive/strong and/or areas of improvement are going to be well communicated. In doing so; the students can be categorically classified to reduce the burden of teachers.

The technical and material supports rendered by the Zone, and Woreda officers as well as cluster school supervisors were not found directly relevant to promote formative assessment on one hand and discriminatory on the other hand. Government schools had gotten sense of ownership by concerned bodies mentioned. Whereas, the private academies though serving children of same population were pushed aside. Thus, establish such groundless, discriminatory and harmful ways of support provisions should immediately be curved and institutional integration better to work on common shared goals.

Prior academic background is believed to have far reaching impact upon (among the scholarly accepted factors affecting) current and future academic success of students of any level. In this regard, pre-primary schooling in rural Bench-Maji Zone in particular was not a well-established practice as depicted in the findings of this study. Only a very few rural schools had begun Early Grade Reading Ability(EGRA) program which enabled students to read, write and count and operate lower level math. The situations in urban centers is different in that; most children are passing through three levels of Kindergarten education. Therefore, the researchers strongly recommend that the Zone Education Bureau should better take the initiation to scale-up the EGRA, as a replica of kindergarten schools of towns, in all rural schools.

The students’ time management experience and the investigation of their study skills shown significant gaps. Their time scheduling experience for academic and non-academic activities, reading books, preparation for tests and note taking experiences as well as study skills need further betterment. Therefore, experience sharing and training forums should be held at cluster schools by the facilitation roles of Woreda Education Office.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Airasian P (1991). Classroom assessment. New York: McGraw-Hill.

|

|

|

|

Alonge M (2004). Measurement and Evaluation in Education and Psychology. Ado-Ekiti, Adebayo Printing Ltd.

|

|

|

|

|

Azimir Premaji Foundation (2006). The Criticality of Pupil Teacher Ratio.

|

|

|

|

|

Baker E, Stites R (1991). Effect of continuous assessment techniques on students' performance.

|

|

|

|

|

Bedard K, Kuhn P (2008). Where Class Size Really Matters: Class Size and Student Ratings of Instructor Effectiveness. Retrieved from: View

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Black P, Wiliam D (1998). "Assessment and Classroom Learning", Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, CARFAX, Oxfordshire 5:1

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Black P, Wiliam D (1998). Inside the Black Box: Raising Standards Through Classroom Assessment. Phi Delta Kappa International @

View

|

|

|

|

|

Black P, Wiliam D (2014). The Impact of Formative Assessment and Learning Intentions on Student Achievement. Retrieved from:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Broadfoot P (2001). New wine in old bottles? The challenge of change for educational assessment, Assessment in Education 8(2):109-112.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Butler A, Phillmann K, Smart L (2001). Active learning within a lecture: Assessing the impact of short, in class writing exercises. Teaching of Psychology 28:257-259.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Clark LH, Starr I (1986). Secondary and Middle School Teaching Methods. USA: New York; Macmillan Publishing Company.

|

|

|

|

|

Cliff J, Imre B (1981). Assessing Students, Appraising Teaching. New York, John Wiley and Sons.

|

|

|

|

|

Cone JD, Foster SL (1991). Training in measurement: always the bribes maid. American Psychologist 46(6):653-654.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Daniel M, Rosenberg B (1998). Recent Research Shows Major Benefits of Small Class Size. American Federation of Teachers 3:1-3.

|

|

|

|

|

Dennis H (2008). Study Skills Inventory. Retrieved from:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Dennis S (2014). Does Class Size Matter? Retrieved on January 18, 2017 from:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Dorothy S (2012). Assessment Matters: Self assessment and Peer assessment. Retrieved on March 4, 2016 from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Elinazi M (2014). Effective management of examinations as a way of achieving quality assurance: A case of the institute of adult education. Retrieved from:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Esther M, Haroon B (2014). The effects of pupil-teacher ratio and expenditure per pupil on educational attainment in South Africa.

|

|

|

|

|

Eugene M, Linda S (1997). Class Size.

|

|

|

|

|

Finn JD, Achilles CM (1990). Answers and questions about class size: A statewide experiment. American Educational Research Journal 27:557–577.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hanover Research (2014). The Impact of Formative Assessment and Learning Intentions on Student Achievement. Retrieved from:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Harlem W, Crick R (2003). The impact of high-stakes examinations on

|

|

|

|

|

Joanne H (2017). Guidelines on examination procedures for invigilators.

|

|

|

|

|

Johnson B, Larry C (2008). Educational research: Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Approaches.

|

|

|

|

|

Joyce L (2013). Examining Classroom Assessment Practices of Secondary School Teachers in Tanzania.

|

|

|

|

|

Laura B, Matthew G, Stephanie L, Saean M (2015). Student Preferences for Small and Large Class Sizes. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 5:1.

|

|

|

|

|

Maddalena T (2005). Assessment: Summative and formative-some

|

|

|

|

|

McKeachie W (2002). McKeachie's teaching tips: Strategies, research, and theory for college and university teachers (11th ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin.

|

|

|

|

|

Ministry of Education (MoE) (1994). Federal Democratic Republic Government of Ethiopia education and training policy Addis Ababa.

|

|

|

|

|

Ministry of Education (MoE) (2013). Harmonized academic policy of Ethiopian public higher education institutions Addis Ababa.

|

|

|

|

|

Morrison K, Tang FHA (2002). Testing to Destruction: a problem in a small state. Assessment in Education 9(3):289-312.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Olufemi AS (2014). Relationship between junior secondary school continuous assessment scores (JSSCAS) and overall JSS ST for male and female students.

|

|

|

|

|

Qualifications and Curriculum Development Agency (2010). Exams invigilation: The essential guide for recruiting and training invigilators.

|

|

|

|

|

Ronald G, Dominic J, Adam G, Douglas J (2006). Class size and student achievement. Retrieved on January 16, 2017 from:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Scottish Qualifications Authority (2015). Guide to Assessment.

|

|

|

|

|