Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

This study aimed at describing a peer-taught program in teaching the English novel course for third-year students at University College of Educational Sciences in Palestine. Through sharing the role of teacher with the students, students were able, with support, to learn and share their learning with their classmates. The major aims of the study were to find out whether the adoption of peer-teaching strategy can enhance the students’ awareness about and achievement in the plot, characters, themes, and symbols of the three assigned English novels and to find out whether the adoption of this strategy can raise the students’ motivation toward this course. Throughout the course, learners spend time summarizing the novels, evaluating the work or ideas of their peers, and explaining rationales—all significant activities that uphold critical thinking and long-term preservation of information. The results of the study showed that peer-teaching strategy has enhanced the students’ motivation and achievement in plot, characters, themes, and symbols of the three English novels.

Key words: Peer-teaching, novel elements, achievement, motivation, long-term preservation.

INTRODUCTION

There are many variations of the word ‘peer coaching’ such as technical coaching, team coaching, collegial coaching, cognitive coaching, and challenge coaching. Technical coaching and team coaching involves new curriculum and instructional techniques into teachers’ habits. Collegial and cognitive coaching look for improving existing teacher practices by refinement techniques, developing collegiality, increasing professional dialogue, and assisting teachers to reflect on their teaching (Showers and Joyce, 1996). Challenge coaching concentrates on identifying and treating a specific problem and can be used in a larger context than the classroom such as a school or grade level (Ackland, 1991).

Showers and Joyce (1996) has examined the history of coaching. Peer coaching started in the early 1980s as a strategy to improve the degree of implementation of new curriculum and instructional techniques. They maintained that “teachers who had a coaching relationship - that is, who shared aspects of teaching, planned together, and pooled their experiences - practiced new skills and strategies more frequently and applied them more appropriately than did their counterparts who worked alone to expand their repertoires” (Showers and Joyce, 1996,). Peer teaching can entail mutual planning, obser-vation, and feedback, rather than serving as traditional and formal evaluation or review, in order to increase the level of performance of instructional techniques and courses (Showers and Joyce, 1996).

Peer tutoring is a brand of peer-mediated, peer-assisted learning, entailing problem solving and systematic teaching strategies to help the slow learners. In addition, Dineen et al. (1977) highlighted that the opportunities for skill practice and social communication are chiefly meaningful for at-risk students. Cross-age tutoring is a peer tutoring approach that brings together students of different ages, with older students having the role of tutor and younger students having the role of tutees. Cross-age tutoring has been successfully applied to students with varying disabilities (Hall and Stegila, 2003). Bruffee (1995) asserted that institutionalized peer tutoring, which began during the 1970s can also be identified as one method of encouraging more student-centered activity, including: self-corrected learning or informal group discussions, to make sure that they are suitable, competent and effective. Peer tutoring is a cost-effectively and educationally valuable intervention that can benefit both the tutor and tutee, socially and educa-tionally by motivating them to learn (Miller et al., 1995).

There are many strategies used by peer coaching programs. These approaches can be classified into establishing a culture of standards and expectations, improving instructional capacity, supporting a process of ongoing evaluation, and connecting classroom practices to policy context. The debate arose in the use of two particular strategies which are incorporating feedback into the peer coaching process and using peer coaching to evaluate learners. The utilization of feedback by mentors in peer coaching classically follows observations as a way to mirror on what was seen.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Hoxby and Weingarth (2005) estimate classroom peer effects for 4th through 8th grade students from Wake County in North Carolina, using the sum of math and reading end-of-year test score levels as the outcome measure. They exploit a recent policy intervention to measure classroom-peer effects, in which some students were reassigned to different schools in a manner that was supposedly random conditional on students’ fixed characteristics. They construct an instrumental variable for the lagged scores of current classroom peers using the initial-period scores and fixed characteristics of the randomly assigned section of the current school-by-grade peer group. The results show significant implications for peer coaching technique.

Zabel (2008) studies data from New York City public schools that indicate classroom assignments but not teacher identifiers. Classroom peer effects are estimated for 4th and 5th grade standardized test scores (in levels), but only school-level fixed effects are used. He takes two approaches: in one case, classroom peer distinctiveness are instrumented by grade-within-school peer characte-ristics, and the second case tests are limited to schools with larger class sizes, within which there is less scope for classroom-level cataloging. This was used to avoid bias from non random classroom assignment within schools. The findings were significant for grade-within-school peer coaching.

Figlio (2005) studied the effects of peer behavior on student performance. He estimated the impact of peer disruptive behavior on individual student behavior and test scores employing data from a single large Florida school district. He controlled the student heterogeneity via student fixed effects. He utilized a novel identification strategy; the fraction of boys with female-sounding names in a classroom is employed as an instrument for peer behavior. He found that peer disruptive behavior is associated with both an improved likelihood that a student is suspended and a reduction in achievement test scores. The current study contributes to the existing stock of peer effects research by providing reliable identification of classroom teachers across a broad range of schooling levels, estimating multiple levels of fixed effects, capturing overflows from unobserved peer ability, and estimating nonlinear models that reveal heterogeneous peer effects with important policy implications.

Betts and Zau (2004) calculate approximately classroom-level effects on standardized test-score gains in San Diego, controlling for student fixed effects and for several observed teacher characteristics. However, they do not employ teacher fixed effects. They also limit their tests to elementary school students, on the grounds that only elementary students spend most of their time in a single classroom and therefore, most likely, are more vulnerable to the authority of classroom peers than are students who move across classrooms throughout the day. Simultaneously, the findings were very significant for the peer coaching and students who were exposed to this technique performed significantly on the test gains.

Peer tutoring and peer counseling have showed good cost-effectiveness, while traditional remedial programmes proved to have very cost-ineffective. Lawson (1989) reviewed 19 colleges and universities in Canada recog-nized as having peer assisted learning programmes. Peer tutoring was found to be more frequent than peer counseling. Detailed reports of goals, selection, training, logistics and methods for evaluation of programmes are provided, but little hard data on comparative effective-ness and cost-effectiveness. Peer assisted learning programmes in the United States medical schools were surveyed by Moore-West et al. (1990). Of 127 colleges in an association, 62 replied and of these, 47 had peer tutoring programmes while 40 had 'advising programmes and 13 had 'peer assessment programmes'. The results showed a very advanced advantage for peer tutoring programmes compared to peer counseling.

Ching and Chang-Chen (2010) have conducted a case study of peer tutoring program in higher education for university students at National Formosa University in Taiwan during academic years 2007 to 2009. There have been 12 tutors providing peer tutoring service, through a Teaching Excellence Project, at the dormitory learning resources center. For the past 3 years, the project has shown to be a true success; tutors now work intimately with tutees, and they also support the instructors during schooling and activity incorporated instruction gatherings. Peer tutoring with skilled and experienced instructors has been one way to encourage extracurricular education services for university students. It is also a technique for improving educational efficiency whereby tutors work together to employ strategies through a systematic process. The findings clearly revealed that the reciprocal peer tutoring programs were flourishing in regard to tutors and tutees’ achievements, motivation and attitudes.

The peer coaching strategies vary among these categories, but all of the programs use peers to achieve the goal of improving the teaching and learning proce-dures. The most ordinary use of peer coaching programs has been for beginning teachers with less than 3 years of experience. Research on orientation programs come across that beginning teachers profit from a formal and structured induction team approach rather than from casual mentoring programs (Klug and Salzman, 1991). Bonelli (1999) maintained that 19 states and the District of Columbia have called for teacher mentoring programs for beginning teachers, and 10 of the remaining states have established voluntary mentoring programs for beginning teachers. The data do not indicate the domi-nance of peer coaching programs for teachers with more than 3 years of experience. Research reveals, though, that peer coaching programs support professional growth, gratitude, experience-enhancing roles, and collegiality for teacher mentors (Killion, 1990).

Showers and Joyce opposed the use of verbal feedback in the peer coaching process because of its similarity to supervision, which weakens collaboration. Rather than promoting a feedback sphere, Showers and Joyce believe that the peer coaching process should focus on the components of planning and developing curriculum and instruction (Showers and Joyce, 1996).

NECESSARY SUPPORT FOR A PEER COACHING PROGRAM

Establishing a culture conducive to collegial and professional interaction is critical. Becker’s (1996) review of peer coaching literature acknowledged effective strategies, as well as a list of support mechanisms that should be incorporated in a peer coaching program:

- Trusting relationships among all participants such as teachers, learners and administrations.

- Emotional, organizational, financial administrative support.

- Faculty and staff credit of the need for improvement and formal continuing learning.

- Clear expectations for engagement.

- Evaluation methods for measuring the outcomes for the experience.

- Release time for peer trainers.

- Funds to pay for training and personnel.

This list emphasizes logistical planning, the significance of trust among participants, stipulation of resources from the administration, and the need for assessment of the initiatives.

PROBLEMS ASSOCIATED WITH PEER COACHING

There are many problems that may result from a peer coaching program such as restricted resources, inadequate training, and lack of evaluation. Research on peer coaching cites the need for quality training for peer coaches to develop an efficient qualified development program (Evertson and Smithey, 2000; Holloway, 2001; Perkins, 1998). Moreover, many schools and universities have limited access to funds for professional development. In peer coaching programs, teachers may frequently use peer teaching without prior arrangements. Additionally, time is required for collaborative planning and development of lesson plans. These are resource and logistics issues that the administration must solve through reallocation and restructuring of the school to ensure an effective program. Developing a formal evaluation process of the peer coaching program at the university level is crucial to the program’s success. Some schools and universities do not have the capacity to decide on the ways that a program impacts teachers and students. Effort should be made to collaborate with local universities or organizations that have the capacity to evaluate peer coaching programs.

Though traditional lecturing proved to be effective inside literature classrooms, very few researches have been conducted to examine the effectiveness of total peer-coaching in teaching the novel course inside universities. This study examines the effectiveness of peer teaching programme for a novel course namely ‘Three Novels: Joseph Andrews for Henry Fielding, Hard Times for Charles Dickens and Jane Eyre for Charlotte Bronte’ at University College of Educational sciences in Palestine.

SIGNIFICANCE OF STUDY

Many teachers of English literature at universities and colleges in Palestine struggle to help learners develop the main skills of English novel courses. While improving language proficiency is the major aim, literature instructors also strive to nurture autonomous, confident learners who work well together, fostering a positive attitude to the language and the university. The use of peer teaching within the English novel lectures would appear to have the scope to enhance learning and student experiences. This study represents an attempt to both describe a peer-taught program in teaching the English novel course for third-year students at University College of educational Sciences. Through sharing the role of teacher with the students, students will be very able, with support, to learn and share their learning with their classrooms.

MAIN QUESTION AND OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY

This study aimed at finding out the effectiveness of peer-teaching inside the English novel classroom at University College of Educational Sciences in Palestine. The main question of the study examines to what extend peer-teaching strategy can raise the achievement of third year students in the English novel course. The sub-questions are:

1. Does peer-teaching enhance the students’ awareness about the plot of the novels?

2. Does peer-teaching enhance the students’ awareness about the characters in the novels?

3. Does peer-teaching enhance the students’ awareness about the themes and symbols of the novels?

4. Does peer-teaching enhance the students’ evaluation and analysis of the different aspects of the novels?

5. Does peer-teaching enhance the students’ motivation inside the English novel course?

The major aims of the study are to find out whether the adoption of peer-teaching strategy can enhance the students’ awareness about the plot, characters, themes, and symbols of the English novels and to find out whether the adoption of this strategy can raise the students’ motivation toward this course.

METHODOLOGY

Design, Sample and Instruments

This study has adopted a study-case design. This study-case consists of a section of the third-year students majoring in English as an intact group at the University College of Educational Sciences in Palestine. The sample consists of 30 students registering the novel course entitled ‘Three Novels: Joseph Andrews for Henry Fielding, Hard Times for Charles Dickens and Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte’. The study was planned for the semester fall of 2013/2014 which entails peer-teaching for 16 weeks. The main instrument of the case-study comprised the use of three standardized tests (First Exam, Second Exam and Third Exam) which measure the students’ achievement in the three mentioned novels. The validity and credibility of the exam were determined by a group of experts on literary studies. They were responsible for piloting the exam items in other universities. A committee of Ph. D. experts took part in evaluating the items of the tests to ensure their validity and credibility. Another qualitative tool was used in which two interviews were conducted to find out the students’ motivation towards the peer-taught course at the end of the semester.

PROCEDURES

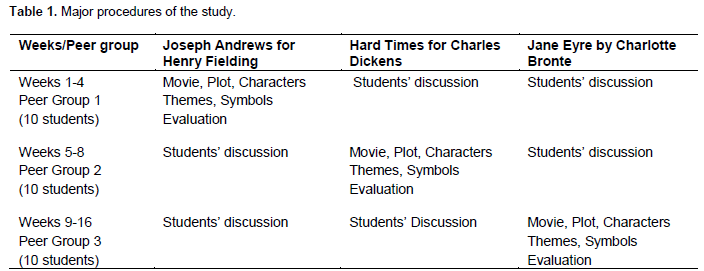

The intact group comprised a section in the University College of Educational Sciences consisting of third-year majoring in English and counting 31 students (7 males and 24 females). The research-er conducted the study using the syllabus ‘Three Novels: Joseph Andrews for Henry Fielding, Hard Times for Charles Dickens and Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte. Table 1 shows the major procedures of the study.

Peer-group 1 which consisted of 10 students was assigned to teach the other two groups the first novel. The time span allowed to the students was five weeks. Within the five weeks, Peer-group 1 performed many tasks such as the proper use of multimedia such as lecturing, discussing, showing movies, power-point presentations and simulations. Peer-group 1 listened to the students’ questions and was able to answer their questions competently. The role of the researcher was mentoring and monitoring the students’ performance with immediate feedback. At the end of the allotted period, the students in Peer-group 1 prepared a bank of questions about the novel ‘Joseph Andrews’ from which a standardized, validated and credibility-tested exam was designed as an achievement test. On October 15, the students sat for the test.

Table 1 also shows that peer-group 2 which consisted of 10 students was assigned to teach the other two groups the second novel. The time span allowed to the students was five weeks. Within the five weeks, Peer-group 2 performed many tasks such as the proper use of multimedia such as lecturing, discussing, showing movies, power-point presentations and simulations. Peer-group 2 listened to the students’ questions and was able to answer their questions proficiently. The role of the researcher was mentoring and monitoring the students’ performance providing immediate feedback. At the end of the allotted period, the students in Peer-group 2 prepared a bank of questions about the novel ‘Hard Times’ from which a standardized, validated and credibility-tested exam was designed as an achievement test. On October 15, the students sat for the first exam.

Table 1 also shows that Peer-group 3 which consisted of 11 students was assigned to teach the other two groups the third novel. The time span allowed to the students was five weeks. Within the five weeks, Peer-group 3 performed many tasks such as the proper use of multimedia such as lecturing, discussing, showing movies, power-point presentations and simulations. Peer-group 3 listened to the students’ questions and was able to answer their questions skillfully. The role of the researcher was mentoring and monitoring the students’ performance providing immediate feedback. At the end of the allotted period, the students in Peer-group 3 prepared a bank of questions about the novel ‘Jane Eyre’ from which a standardized, validated and credibility-tested exam was designed as an achievement test. On October 15, the students sat for the first exam.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

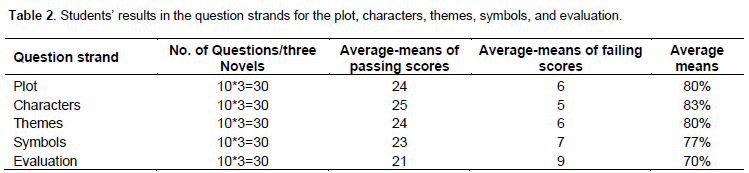

Table 2 represented in Figure 1 shows the students’ results in the question strands for the plot, characters, themes, symbols, and evaluation. Figure 1 shows the students’ results in the English Novel course. The figure answers the following questions:

Question 1

Does peer-teaching enhance the students’ awareness about the plot of the novels?

The results of the standardized test are significant for this question. The average-means of passing scores was 24 out of 30. That means that the total score is 80%. Due to peer-coaching, the students were able to identify the major events in the three novels and were also to recognize the plot organization. They were also able to arrange the events subsequently. These results were in harmony of Ching and Chang-Chen (2010) who found peer-teaching as an effective strategy in literature. It was obvious that when students worked individually, conducted study groups, and performed some sketches of the different novels, they have strengthened their knowledge in the literary plot of the different novels.

Question 2

Does peer-teaching enhance the students’ awareness about the characters in the novels?

The results of the standardized test are significant for this question. The average-means of passing scores was 25 out of 30. That means that the total score is around 85%. Due to peer-coaching, the students were able to identify the major characters in the three novels and were also to recognize their roles and link to the plot. They were also able to analyze the major characters and their implications. These results were in harmony of Figlio (2005) who studied the effects of peer behavior on student performance and found peer-teaching as an effective strategy in literature. It was obvious that when students had identified the characters, analyzed them, conducted study groups, and performed some sketches of the different characters, they have broadened their knowledge in the literary plot of the different novels.

Question 3

Does peer-teaching enhance the students’ awareness about the themes and symbols of the novels?

The results of the standardized test are significant for this question. The average-means of passing scores was 23 out of 30. That means that the total score is around 80%. Due to peer-teaching, the students were able to identify the major themes and symbols in the three novels and were also to recognize their significance. They were also able to analyze the major themes and their implications. These results were in harmony of Hall and Stegila (2003) and Bruffee (1995) who studied the effects of peer behavior on student performance and found peer-teaching as an effective strategy. It was obvious that when students had identified the themes and symbols, analyzed them, conducted study groups, and presented some power point presentations, they have widened their knowledge in the literary themes and symbols of the different novels.

Question 4

Does peer-teaching enhance the students’ evaluation and analysis of the different aspects of the novels?

The results of the standardized test are significant for this question. The average-means of passing scores was 21 out of 30. That means that the total score is around 70%. Due to peer-teaching, the students were able to evaluate the major plot, characters, themes and symbols in the three novels and were also to provide each other with their opinions. They were also able to analyze the major aspects of the novels and find their implications. These results were in harmony of Hoxby and Weingarth (2005) and Zabel (2008) who found that peer behavior can raise the students’ performance and found peer-teaching as an effective strategy. It was obvious that when students had evaluated the plot, themes, symbols, analyzed them and given their point of views about them through study groups, they have expanded their knowledge about the evaluation strategy about the different novels.

Question 5

Does peer-teaching enhance the students’ motivation inside the English novel course?

The results coming from the students’ interviews are significant for this question. Students are likely to be intrinsically motivated (a) if they attribute their educational results to factors under their own control, also known as autonomy, (b) if they believe they have the skills to be effective agents in reaching their desired goals, also known as self-efficacy beliefs and (3) if they are interested in mastering a topic, not just in achieving good grades. On the other hand, extrinsic motivation refers to the performance of an activity in order to achieve an outcome, whether or not that activity is also intrinsically motivated. Extrinsic motivation comes from outside of the students. Common extrinsic motivations are rewards (for example grades) for showing the desired behavior, and the threat of punishment following misbehavior (Richard and Deci, 2000). The results show that peer-teaching has improved both the intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. These findings adhere with Pritchard and Ashwood (2008) who maintained that peer coaching can raise the students’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.

CONCLUSION, LIMITATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Lecturers who involve their learners in peer teaching can share aspects of teaching, plan together, pool their experiences, practice new skills and strategies more frequently. Learners who work in groups can perform better on tests, mainly in regard to reasoning and critical thinking skills (Lord, 2001). Involving students to work with each other is an effective methodology because it forces students to be energetic learners and to talk through course concepts in their own words. However, there are many variations on how peer teaching can be used to boost learning inside the classroom. Goto and Schneider (2010) maintained that peer activities can be very efficient in getting students to engage in critical thinking; hence, producing deeper learning results.

This study represents an attempt to both describe a peer-taught program in teaching the English novel course for third-year students at University College of Educational Sciences. Through sharing the role of teacher with the students, students were able, with support, to learn and share their learning with their classmates. The major aims of the study were to find out whether the adoption of peer-teaching strategy can enhance the students’ awareness about the plot, characters, themes, and symbols of the English novels and to find out whether the adoption of this strategy can raise the students’ motivation toward this course.

The results of the study showed that peer-teaching strategy has enhanced the students’ socialization and their achievement in plot, characters, themes, and symbols of the English novels. Throughout the course, learners spend time summarizing the novels, evaluating the work or ideas of their peers, and explaining rationales - all significant activities that uphold critical thinking and long-term preservation of information. This type of peer instruction is connected with the backing of critical thinking skills as well as understanding of intricate literary concepts (Goto and Schneider, 2010). However, it has been of great importance that instructors should instantly notice where clarification might be needed based on what the groups struggled with, or when they tremendously chose incorrect answers (Simon et al., 2010). Dioso-Henson (2012) has found that peer-teaching can be of great efficacy to help college students perform better in exams due to the shared experience among the peers.

One, however, cannot ignore the limitations of peer-teaching. The focal group of the study is rather small; therefore, we cannot over generalize the results of this study. It is tricky to grade each team member syste-matically, according to their performance. The researcher has suggested a way to minimize the problems faced with this dilemma. The students were asked to evaluate their peers and themselves. By assessing themselves, learners were more likely to produce more sensible results. It should be highlighted that learners tend to view themselves and their peers as too inexperienced to be making precise and reasonable assessments of their work. This is chiefly factual when students are receiving grades based on peer feedback (Kaufman and Schunn, 2011). The researcher has asked the students to prepare suggested exam questions. By this, the students have been involved indirectly in receiving grades based on peer feedback. It was noticed that students tend to judge themselves and their peers rather generously. Thus, it has been suggested that peer assessment may need to be implemented for a considerable amount of time before accurate results can be expected. Peer-teaching is sometimes challenging because there is supposed to be an equal work load, in which all members do not do their part. Workloads should be shared proportionally and group members ought to contribute equally. It has been obvious that few members might work harder than their irresponsible peers. Students generally question the ability of peers to assess their work, and the value of the feedback being received. It might be very essential to have other researches to explore the effectiveness of per-teaching in bridging the individual difference among peers.

REFERENCES

| Ackland R (1991). A review of the peer coaching literature. J.Staff Dev. 12(1):22-6. | ||||

| Becker JM (1996). Peer coaching for improvement of teaching and learning. Teachers Network. Retrieved on February 6, 2013, from http://www.teachnet.org/TNPI/research/growth/becker.htm. | ||||

| Betts JR, Zau A (2004). "Peer Groups and Academic Achievement: Panel Evidence from Administrative Data." unpublished manuscript. | ||||

| Bonelli J (1999). Beginning Teacher Mentoring Programs. Education Commission of the States. Retrieved on February 6, 2013, from http://www.ecs.org/clearinghouse/13/15/1315.doc. | ||||

| Bruffee K (1995). Collaborative learning: Higher education, interdependence, and the authority of knowledge. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. | ||||

| Ching C, Chen L (2011). A case study of peer tutoring program in higher education. Res. Higher Educ. J. 11:1-10. | ||||

|

Dineen JP, Clark HB, Risley TR (1977). Peer tutoring among elementary students: Educational benefits to the tutors. J. Appl. Behav Anal. 10: 231-238. Crossref |

||||

|

Dioso-Henson L (2012). The effect of reciprocal peer tutoring and non-reciprocal peer tutoring on the performance of students in college physics. Res. Educ. 87(1):34-49. Crossref |

||||

|

Evertson C, Smithey M (2000). Mentoring effects on protégés' classroom practice: An experimental field study. J. Educ. Res. 93(5):294–304. Crossref |

||||

| Figlio DN (2005). "Boys Named Sue: Disruptive Children and Their Peers." NBER working paper #11277. Cambridge, MA: NBER. | ||||

|

Goto K, Schneider J (2010). Learning through teaching: Challenges and opportunities in facilitating student learning in food science and nutrition by using the inter-teaching approach. J. Food Sci. Educ. 9(1):31-35. Crossref |

||||

| Hall T, Stegila A (2003). Peer Mediated Instruction and Intervention. Retrieved July 10, 2013, from http://www.cast.org/publications/ncac/ncac_peermii.html | ||||

| Holloway JH (2001). Research Link/The Benefits of Mentoring. Educ. Leadersh. 58(8). | ||||

| Hoxby CM, Gretchen W (2005). Taking Race Out of the Equation: School Reassignment and the Structure of Peer Effects. unpublished manuscript. | ||||

|

Kaufman JH, Schunn CD (2011). Students' perceptions about peer assessment for writing: their origin and impact on revision work. Instruct. Sci. 39(3):387-406. doi:10.1007/s11251-010-9133-6. Crossref |

||||

| Killion JP (1990). The benefits of an induction program for experienced teachers. J. Staff Dev. 11(4):32-36. | ||||

|

Klug BJ, Salzman SA (1991). Formal induction vs. informal mentoring: Comparative effects and outcomes. Teaching Teacher Educ. 7:241–251. Crossref |

||||

|

Lord T (2001). 101 reasons for using cooperative learning in biology teaching. Am. Biol. Teacher 63(1):30-38. Crossref |

||||

|

Miller SR, Miller PF, Armentrout FJA (1995). Cross-age peer tutoring: A strategy for promoting self-determination in students with severe emotional disabilities/behavior disorders. Prev. School Failure 39(4):32-37. Crossref |

||||

|

Moore-West, M, Hennessy A, Meilman PW, O'Donnell JF (1990). 'The presence of student-based peer advising, peer tutoring and performance evaluation programs among U.S. medical schools', Acad. Med. 65(10):660-661. Crossref |

||||

| Perkins SJ (1998). On becoming a peer coach: Practices, identities, and beliefs of inexperienced coaches. J. Curriculum Supervision 13(3):235–254. | ||||

| Pritchard R, Ashwood E (2008). Managing Motivation. New York: Taylor & Francis Group. p.6. ISBN 978-1-84169-789-5. | ||||

|

Richard R, Deci EL (2000). "Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions". Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 25(1):54-67. Crossref |

||||

|

Simon B, Kohanfars M, Lee J, Tamayo K, Cutts Q (2010). Experience report: peer instruction in introductory computing. Proceedings of the 41st ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education, 341-345. Crossref |

||||

| Showers B, Joyce B (1996). The Evolution of Peer Coaching. Educ. Leadersh. 53(6):12-16. | ||||

| Zabel JE (2008). The Impact of Peer Effects on Student Outcomes in New York City Public Schools. Educ. Finance Pol. pp.197-249. | ||||

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0