ABSTRACT

Competence-based education (CBE) has been increasingly emphasized in optimising the preparation of healthcare professionals. Uganda like many other countries of the world, has taken considerable strides in implementing CBE training of nurses and midwives. The aim of this study was to investigate the perception of professionals regarding appropriateness of the CBE curriculum content in terms of organisation, clarity, relevance and suitability in training programs of nurses and midwives of Uganda. The study was conducted at Mulago National Referral Hospital (MNRH) that recruits the biggest number of trained CBE nurses and midwives. The study used concurrent mixed methods to gather both quantitative and qualitative data from respondents. It used a total sample of 193 professionals comprising of 102 CBE trained participants and 91 Key stakeholders. Findings of this study indicate that the CBE curriculum content used in the training of nurses and midwives was appropriate. However, it was concluded that the CBE curriculum implementation process remains a challenge due to inadequate sensitization of implementers, as well as standardization of the CBE curriculum content implementation process. It was recommended that sensitization and orientation of stakeholders is necessary for adapting the CBE curriculum content in the training of nurses and midwives.

Key words: Competence-Based-Education, curriculum content appropriateness, quality healthcare, service delivery, competences, skilled nurses and midwives.

Delivering appropriate health care services is fundamental for the human wellbeing. Nurses and midwives are the backbone of hospital based and community healthcare service delivery worldwide (Adib-Hajbaghery, 2013; WHO, 2009). Thus, a lot of emphasis is being put on the quality of their training and acquisition of the needed skills to become effective healthcare professionals. Increased attention is currently being given to Competence-Based Education (CBE) as a means of optimizing the preparation of healthcare professionals (Gruppen et al., 2010). CBE is an outcomes-based approach to the design, implementation, assessment, and evaluation of education programs (Boyd et al., 2018; Frank et al., 2010; Pijl-Zieber et al., 2014). It is a framework for designing and implementing education that focuses on the desired performance characteristics, and acquisition of expected attitudes, skills, and knowledge by trainees that are necessary for them to offer quality healthcare services (Carraccio et al., 2002; Eraut, 1994; Josephsen, 2014). The CBE training approach centres on knowledge application, emphasizing outcomes rather than knowledge acquisition (Glasgow et al., 2017; LaLiberte and Hewitt, 2007; NVSC, 2002). This approach is pro-active, which provides a link between theoretical curriculum content and activities for practice thus facilitating trainees’ active engagement and participation during their hands on preparation (Billett, 2016; Lunenburg, 2011; Redman et al., 1999; Tilley et al., 2007). This enables trainees to gain the needed competences and a deeper understanding of their profession. It is therefore important to have an appropriate, clear, relevant and suitable curriculum content that is in line with the stated objectives for program needs, ultimately leading to the achievement of the intended outcomes in the field of study (Arafeh, 2016; Norton, 1987).

A well designed curriculum creates a match of the competences with patient and population needs (Frenk et al., 2010; Sargeant et al., 2018)ensuring the content is clear to provide the necessary behavioural change for students’ understanding of concepts that imparts expected skills for learners and their behaviours (Jephcote and Salisbury, 2009; Medina, 2017; Muraraneza and Mtshali, 2018). In addition, relevance of the curriculum content enables the trainee to construct and conditionalize knowledge during clinical practice on their own efforts to offer quality health care services (Feldman and McPhee, 2007; Redman et al., 1999; Wall et al., 2014). Understanding the appropriateness of the curriculum content within particular contexts could help in coming up with strategies to improve health care education that meets the public needs within that setting. Uganda like many other countries of the world has also taken considerable strides in implementing CBE training approach for nurses and midwives. However, no study has been done to determine the CBE curriculum content appropriateness in all training programs of nurses and midwives, especially with emphasis on meeting the ever changing needs/demands for quality health care services. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to investigate the appropriateness of the CBE curriculum content in training programs of nurses and midwives in Uganda. Specifically, the perceptions of health professionals provided a framework for our better understanding of the appropriateness of the CBE Curriculum content during the preparation of competent Nurses and Midwives in Uganda.

Design and sample

This cross-sectional study adopted a concurrent mixed method design with both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods. It used a total sample of 193 professionals who comprised of 102 CBE trained participants and 91 Key stakeholders. A total population of 143 nurses and midwives trained under the CBE program were currently working at Mulago National Referral Hospital (MNRH), at the time of the study. The researchers used the convenience sampling technique to select 103 CBE trained nurses and midwives out of whom 102 responded to the questionnaire. Only the nurses and midwives with diplomas who were trained on the CBE curriculum within the period of 2008 to 2014 and working in specialised areas at Mulago National Referral Hospital (MNRH) at the time of study, participated in the study. Each of the participants gave an informed consent to respond to a self-administered questionnaire. Excluded from the study, were nurses and midwives who completed their training before 2008 and were not trained on the CBE curriculum as well as preceptors/ ward in-charges who were not working in ward/ areas of specialization. Thereafter, purposive sampling was used to select a total of 91 key stakeholders who are involved in the training of nurses and midwives; out of whom 66 preceptors were ward in-charges and the immediate supervisors of Nurses and Midwives in clinical practice. These participated in Focus Group Discussion (FGDs). The remaining 25 key stakeholders responded as key informants for the in-depth interviews. These included: school principals, tutors, and hospital administrators/consultants, officials at both Uganda Nursing and Midwifery Examination Board (UNMEB) and Uganda Nurses and Midwives Council (UNMC), Ministry of Education and Sports (MoES)and Ministry of Health officials. Therefore, the study used a total sample of 193 respondents comprising of above mentioned professionals.

Instruments

The study utilized several research tools including a questionnaire, FGD and In-depth Interview guides. The questionnaire consisted of closed-ended questions that were rated on a 3 point Likert scale. Scale 3 represented those who agreed, Scale 2 undecided while Scale 1 those that disagreed on items regarding the CBE Curriculum Content implementation and the quality of health care service delivery. The FGDs and in-depth interview guides comprised of a set of open ended questions that was used by the moderator to solicit views of FGDs and Key informants respectively.

Data collection

Data collection was undertaken from March to April 2015. The key study participants were nursing and midwifery service providers who had undergone the CBE curriculum training from 2008 to 2014. They were requested to individually complete the questionnaires. On the other hand, FGDs and In-depth interviews were scheduled with key informants within the same period. The FGDs data was collected from preceptors/ward in-charges working in the areas of specialization at MNRH, where hands-on competences are required for life saving tasks such as managing head injuries and conducting baby deliveries. Three participants from each ward were selected according to their order of seniority. The groups comprised of 9-10 preceptors/ward In-Charges. The participants were invited during lunch breaks, to avoid unnecessary interruption of their busy schedules. The FGDs were conducted for 45-60 min. The allocated time was sufficient and did not affect study findings. Participants were given a meal in compensation for their lunch break. Two FGDs were held on each day. Data collection exercise was carried out for five days. The gathered data was audio recorded, stored on a computer as well as external drives.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by both the postgraduate research committee of Makerere University College of Education and External Studies (CEES) and Mulago National Referral Hospital. Clearance was obtained from the Mulago Hospital Research and Ethics Committee (Protocol Number MREC: 694). The approval letter was presented to the participants. In addition, the purpose of the study, confidentiality, voluntary participation, and freedom to withdrawal, were clearly explained to the participants ahead of signing a consent form to confirm their acceptance to participate in the study.

Data analysis

Quantitative data from the questionnaires with a 3 Likert scale of Disagree, Undecided and Agree was presented using tables and figures for ease of analysis, using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21. Descriptive statistics were generated in form of frequencies and percentages. On the other hand, qualitative data was transcribed into Microsoft word after each of the FGDs and in-depth interview session. The investigators worked independently to review transcribed information with reference to the original data that is hand written and electronically recorded. This massive qualitative data from FGDs and in-depth interviews was analysed for content and merging common themes /sub-themes, informed by the Grounded Theory. Coding of the data was done by hand, using a number for each FGD participant, while KI coding was done by allocating “ID” and an institutional number. This enabled greater visualisation of the data (McCann and Clark, 2003). There were three major themes that rose from the recorded data namely; adaptation, sensitization and standardisation.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by both the postgraduate research committee of Makerere University College of Education and External Studies (CEES) and Mulago National Referral Hospital. Clearance was obtained from the Mulago Hospital Research and Ethics Committee (Protocol Number MREC: 694). The approval letter was presented to the participants. In addition, the purpose of the study, confidentiality, voluntary participation, and freedom to withdrawal were clearly explained to the participants ahead of signing a consent form to confirm their acceptance to participate in the study.

Year of completion and area of operation of respondents

The year of completion of the training of participants who went through the CBE program and were working in MNRH as was between 2008 and 2014 (Figure 1). Majority (33.3%) of the participants were pioneer CBE trained nurses and midwives who graduated in 2008. However, with subsequent years, the number of recruited CBE trained nurses and midwives decreased according to the employment needs at MNRH. Sixty three percent of the participants were from the nursing section while 37% were from the midwifery section. Additionally, most participants operated from wards where general healthcare conditions are treated such as surgical (16.7%) and medical (15.7%). The midwives were assigned to mother and baby lifesaving areas especially in labor wards (12%), postnatal wards (6%) and antenatal clinics (5%) (Figure 2). This implies that participants in this study were contributing extensively to critical clinical healthcare which increasingly demands for highly specialized competences in contemporary hospitals.

Appropriateness of the CBE curriculum content and quality healthcare service delivery

Participants’ opinions about appropriateness of the CBE curriculum content undertaken during their training as nurses and midwives were investigated. The responses focused on four parameters namely; content organization, clarity, relevance, and suitability. Findings from Table 1 reveal that the majority of respondents (that is 72-77%) agreed that the CBE curriculum content organization was appropriate for both the nurses and midwives training programs. They also observed that it adequately enhanced appropriate attitudes, skills and knowhow required for delivering quality healthcare services. The topics were also well sequenced and the content addressed a wide range of contemporary diverse healthcare conditions in clinical practice. This is reflected in the following quotations: “It addresses health needs because there is clinical component whereby students are given lectures on the wards, there is also coaching, mentoring and demonstrations. So students learn and are able to reflect on current health needs’’ (FGD5).

Similarly, in one of the in-depth interviews it was observed that nursing and midwifery trainees are taken through a systematic training approach that is being trained in theory before getting to other fields of learning (hands-on, clinical practice, etc.) as reflected in the following quotation:

“Yes because when students have just come we teach them according to the same level, we start with theoretical courses such as foundation of nursing, anatomy and physiology so that they become well acquainted/grounded with those before we move on to other clinical practical fields’’ (ID04TDP).

In another in-depth interview, it was also observed that the curriculum content organization was well sequenced starting with basic introductory topics/courses before bringing in other courses with more demanding and complex competences in clinical practice. “It is well sequenced because it begins from the introduction and other complex components follow.’’ (ID010EB). However, it was also noted that when trainees go to clinical practice they experience and see different conditions compared to what has been taught in the classroom. This is reflected in the following quotation:

“The only challenge is that when our students come there is a period we ask them to go to the ward and when they go to the wards they see different conditions from those covered at school.’’ (ID010EB).

As such the trainees are often disoriented in linking theory to practice, given that the conditions in clinical practice are unpredictable as they emerge in real life situation. Hence, the disparity between what has been taught in the classroom and what exists in the clinical area continues to be a challenge. This can be catered for if trainees are guided by their clinical supervisors to relate the knowledge and skills gained through the CBE and skills training program. Nevertheless, a few respondents had different views towards the appropriateness of the curriculum organization. They indicated that much as the curriculum content enables trainees to acquire the needed competences for offering quality healthcare services, effective adoption of CBE training programs remained a challenge to the implementers. This implies that different tutors may teach varying topics to different groups of students, consequently, the standardization of the teaching may be compromised. This is reflected in the quotation that follows:

“The organization is okay though the challenge is the semester system. It does not specify what is to be taught in a particular semester but it looks at the entire year. So it depends on the person to teach to decide’’ (010EB).

Another respondent also observed that some areas were not well catered for in the organization of the curriculum content. This is reflected in the following quotation:

It does but it is sort of limited. Now we have other subjects that are not catered for in this curriculum of 2006. For example, in Obstetrics things like nursing process are not catered for in the curriculum (ID08TMT).

This is an important observation and it presents implications for the need of curriculum review and reform that is long overdue. A few participants noted that the curriculum content was not well organized. This is reflected in a quotation:

“Diploma trainees have abnormal midwifery and normal midwifery done in a period of six months. However, you cannot teach abnormal midwifery before teaching normal midwifery” (FGD1).

This is true in clinical practice where normal and abnormal conditions are usually handled concurrently. Therefore trainees during clinical practice are faced with all conditions as found in clinical placement. It is therefore important for the clinical supervisor to guide trainees for all clinical conditions as they naturally occur, because their occurrence is unpredictable. It is therefore advisable to sensitize all clinical supervisors to CBE training. What comes out clearly from the findings are the divergent views regarding the appropriateness of the curriculum content being used in CBE training programs of nurses and midwives offering healthcare services. Some stakeholders expressed their dissatisfaction towards the declining competences of nurses and midwives completing CBE training programs. They argued that the nurses and midwives currently graduating actually lacked the needed competences (that is attitudes, skills, and knowhow) required to offer quality healthcare services. They also felt that the CBE curriculum content was not comprehensive enough to meet the current demands of contemporary clinical practice as reflected in the following quotation:

It is fair though there are some important things missing. For example, I teach community health and you find that there are some components like disaster management, occupational health which don’t come out well. In service management, the things which are there are a brief outline but don’t really give what you should teach. The learners’ guide and tutors’ guide are missing and actually the content is not appropriate. (ID06TNT).

This further implies the necessity for a curriculum review and the need to develop appropriate learners’ and trainers’ guides. These are required during the training since the curriculum gives only an outline without providing details. On the contrary, most of the other stakeholders felt satisfied with the appropriateness of the CBE curriculum content, for instance, they felt that the CBE curriculum content imparts the desired competences for nurses and midwives as reflected in the quotation:

It does help in acquisition of knowledge, skills, and attitudes (ID09NMC).

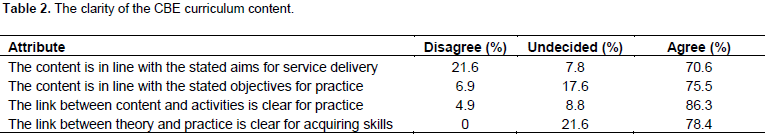

The clarity of the CBE curriculum content

The results regarding clarity of curriculum content of the CBE training programs are satisfactory in terms of imparting the needed competences to nurses and midwives as reflected by the high percentage of agreement that is 71-86% as shown in Table 2. Findings of the FGDs revealed that the CBE curriculum content was clear and gave the trainees the needed competences without necessarily depending so much on their tutors. This is reflected in the following quotation:

Students are given chance to know what exactly they are supposed to cover such that even if the teacher is not there they can read alone and minimize chances of missed out information (FGD1).

A participant among the ward supervisors also supported clarity of the CBE curriculum content because it covered everything trainees needed to know, although she noted that some students were dodging some of the clinical practice skills and yet they wanted to be signed off as having been learnt. This is reflected in a quotation that follows:

‘’It covers everything but there are those students who dodge practical work and disappear only to return later crying and asking for signatures on their report forms. However the content clarity is okay’’ (FGD3).

The likely consequences of dodging clinical practice are producing incompetent practitioners who are a high risk to the public. This signifies the need for clinical supervisors to maintain the required clinical contact hours stated in the curriculum. Short of this, the situation may call for a subsequent study as to why students dodge clinical practice which is vital for acquiring competences. Another ward supervisor was also in agreement that CBE curriculum content was clear and adequately covered the objectives. Clear and adequately stated objectives helped trainees to work independently during clinical placement requiring minimal support from the Preceptors/ Ward in-charges, they asked questions when it was necessary. This is reflected in the following quotation:

“It is adequate because the students I received in the last clinical placement came to the ward with objectives for clinical practice and didn’t need constant supervision, they would only seek for help when necessary. So the curriculum content was adequate” (FGD4).

Findings from the In-depth interview also revealed that much as the CBE curriculum content was clear and appropriate, many students spent more time doing classroom assignments and gave less time to clinical practice where they were required to demonstrate their knowhow. This is reflected in the following quotation:

The content is okay but when it comes to practical work most of the times students are in the classroom and therefore less time for clinical practical work (ID04TMT).

This phenomenon undermines clinical learning experiences, a situation to be addressed by all CBE players for proper implementation.

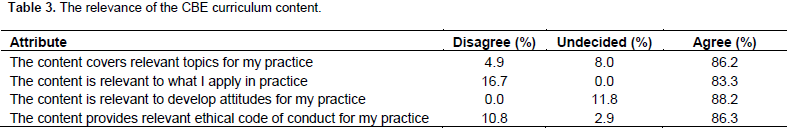

The relevance of the CBE curriculum content

It was also important to establish the perception of the respondents regarding relevance of the CBE curriculum content they studied as presented in Table 3. Findings clearly revealed that the CBE curriculum content is relevant in providing the needed competences (that is attitudes, skills and knowhow) as required in the clinical related workplace. For instance, the former CBE trained nurses and midwives agreed that the curriculum content used during their training addressed the expected competences needed to offer quality healthcare services. This is reflected in the following quotation:

“It does because once a student gets this competence and she is ready to go to the community she will be able to act accordingly’’ (FGD1).

Furthermore, one of the ward supervisors in a clinical placement site noted that the curriculum content was relevant and had adequate objectives. However, she also observed that some students demonstrated negative attitudes for some clinical practical activities. This is reflected in the following quotation:

Yes the objectives are adequate but the students’ attitudes are negative. We are really chasing them around as they are taught in the clinical area, in other words the objectives are adequate (FGD2). This implies that the situation of student attitude towards clinical learning needs to be investigated for rectification.

Another former CBE trainee was of the opinion that the curriculum content was so relevant to the experiential practice for the learning needs of today. She stated in the following quotation:

“So relevant in that students do more of hands-on experience. When you learn something where you have placed your hands, you cannot forget it easily. I believe it’s really relevant to learning needs of today’’ (FGD1).

On the other hand, some respondents felt that the curriculum relevance was quite limited, especially regarding the time of exposure in clinical practice. They indicated that some tutors were still generic and continued to use didactic teaching approaches because they lacked the needed orientation on CBE curriculum implementation. Their comments were as follows:

There are inadequacies in terms of content and the time for exposure is still limited. The tutors are quite generic in their approach. They are not taken through on how to implement CBE and resort to the traditional approach (ID012MH).

Not in the technical manner because I have not been exposed to that field of training although I have heard of problem based learning. I have not heard about CBE but I understand the concept (ID06TPO)

It is not surprising that the quality of nurses and midwives completing training in recent years is perceived as deteriorating. It is also a pity that majority of trainees are missing out and are reluctant on clinical practical activities. This came out clearly during FGDs where one respondent noted that trainees might be knowledgeable in theory but low in clinical practice. This clinical practice gap was created by the rampant students’ absenteeism and consequently staff members lose interest and do not pay the needed attention to them as indicated in the following quotation:

They are knowledgeable because they have theory but when they come to practice, they are not able to practice. The gap is in the clinical practicum area. At times when they come they present a lot of absenteeism cases and the staff lose confidence in them and do not pay attention to them because they do things the way they think (FGD6).

The suitability of the CBE curriculum content

Similarly, the study sought to ascertain the suitability of the curriculum content used in CBE nursing and midwifery programs in meeting the quality of healthcare services needed in clinical practice. Four questions were posed to the CBE graduates and their views are summarized in Table 4. Most of the participants agreed that the curriculum content was suitable and gave them a chance to cover what they were required to know in the nursing and midwifery programs. The participants also revealed that they could read to beef up the missed information from their tutors as stated in the following quotations:

“Students are given chance to know what exactly they are supposed to cover such that even if the tutor is not there they can read alone and minimize chances of missed out information’’ (FGD1). In the past a lot of theory was dominating the training of nurses and midwives but we found that they needed more hands-on because the graduates’ work is purely hands-on and so CBE would lead us to those kinds of skills. (ID011ES) Worldwide it’s the trend. You cannot just teach knowledge, people must be able to perform. So the concept of CBE is the way to go (ID011ES).

The curriculum content is viewed to be suitable for training competent nurses and midwives for delivering quality healthcare services. However, some supervisors in the clinical area were of different views that tutors running the CBE program were too few to accomplish coverage of the required curriculum content as implied in the following quotation:

Content is good but tutors are not enough to cover what they are supposed to cover in the theory part. For us in clinical area we expect students to come after covering theory so that they can put it into practice in the clinical area (FGD2).

This is a challenge for the concerned Ministry to put right, to ensure that a sufficient number of tutors is recruited, and to follow and support students during clinical practice in order to create an enabling environment to link theory with practice.

Appropriateness of the CBE curriculum

This study examined the perception of professionals regarding the appropriateness of the CBE curriculum content in training programs of nurses and midwives in Uganda. The professionals interviewed agreed that the curriculum content used in the implementation of CBE training programs of nurses and midwives, achieved the intended goal of preparing skilled professionals. Still the professionals interviewed considered the curriculum content appropriate for imparting the expected competences. However, the results may not be extrapolated to other nursing/midwifery training institutions in Uganda. This is because the sample took into account participants working at MNRH, the only hospital with comprehensive specialized clinical areas. This implies that the CBE curriculum content used in the Nurses and Midwives training programs, emphasized acquisition of the performance-based learning outcomes, for achieving pre-determined competencies for clinical practice (Pijl-Zieber et al., 2014). Putting emphasis on performance and learning outcomes in order to produce quality nurses and midwives for healthcare service delivery is consistent with the increasing demand for contemporary nurses and midwives all over the clinical related world of work, especially in developing countries. This is because the quality of healthcare services is dependent on the quality of training programs used to produce nurses and midwives who are endowed with the expected competences to address healthcare needs (Barksdale et al., 2014; Uys and Gwele, 2005).

The professionals’ responses observed that the curriculum content appropriateness in terms of organization, clarity, relevance and suitability followed a systematic framework approach to training, for example, starting with simpler to complex content. The sequenced and systematic approach of the curriculum content enabled learners to acquire the expected competences that are transferable to clinical practice to link theory and practice (Billett, 2016; Wall et al., 2014; Wesselink et al., 2003). There is need for a paradigm shift from the traditional didactic teacher-centered teaching approach to providing learners with expected competences for performing the job (Muraraneza and Mtshali, 2018; Thanh, 2010). Findings of this study further revealed that the curriculum content was considered to be clear, relevant and suitable in terms of developing the needed attitudes, skills, and knowhow of nurses and midwives to offer quality healthcare services. However, there are professionals’ concerns about the adaptation of CBE by stakeholders, especially as regards inconsistent implementation of the different curriculum content/subject areas to different cohorts of students. This of course undermines the quality of training of nurses and midwives (Dlamini et al., 2014). The respondents agreed that standardization of the CBE program and sensitization of key players (educators and students) was extremely vital. As such, curriculum stakeholders i.e. educators, clinical supervisors, policy makers and students themselves should put in place the structures for enabling smooth linkages between theory and practice as emphasized by the CBE training approaches.

Appropriate curriculum content and structures are not enough, given the inadequate numbers of tutors and clinical supervisors. These concerns also need to be addressed. Otherwise, the competence of nurses and midwives going through the CBE programs and the quality of their health care service delivery are questionable (Dlamini et al., 2014; Komba and Mwandaji, 2015). This finding alludes to the fact that many other factors may contribute to inadequate provision of quality health care service delivery, which quite often results into high maternal and infant mortality rate (Ministry of Health, 2007; MoES, 2012). These findings are confirmed by a study done in Uganda on the factors affecting the quality of health care services (Kiguli et al., 2009)which are also consistent with those in other developing countries (Anthopoulou et al., 2017; Botma, 2014; Kadri et al., 2017; Muraraneza et al., 2017). It requires extraordinary efforts on part of stakeholders to address the perceived factors that may interfere with curriculum content implementation, to enable nurses and midwives achieve the desired outcomes. This is affirmed by Flanagan et al. (2000)who found that suitable curriculum content was highly associated with acquisition of favorable learning outcomes and competences.

Indeed, various implementers should play a major role in enhancing CBE training implementation for quality service delivery (Frenk et al., 2010). What comes out clearly from this study is that organization and implementation of the curriculum content in CBE training programs has issues that need to be addressed. For instance, issues with the integration of relevant knowledge, skills, values and attitudes during clinical performance/practicums, in order to prepare skilled nurses and midwives. These clinical performance/practicums give opportunities to students to gain experiential peer learning and hands-on practical experiences in real life clinical settings. It implies that through real life experience, the trainees acquire/learn transferable skills from theory to practice (HCCA, 2012). This notion is in agreement with the emphasis put on practical performance and ability to do (Josephsen, 2014; LaLiberte and Hewitt, 2007)as emphasized in the CBE approach. The drive to ensure that nurses and midwives are able to actually perform practical skills is intended to bridge the gap between the demands of the labor market and the school system (Van Melle et al., 2017; Wesselink et al., 2003).

Therefore, trainees are prepared through a suitable CBE curriculum, to enable them competently perform clinical skills to the satisfaction of health needs in Uganda and beyond. As such, all stakeholders involved in CBE implementation of the nurses and midwives training program need to become well acquainted with the CBE curriculum content in terms of its adaptation for proper implementation. This can be done through sensitization workshops, and orientation with curriculum structures and standards to enhance the proper implementation of CBE training programs. It is also important to carry out curriculum reviews in order to identify and bridge existing gaps as well as addressing other areas of concern. Through these efforts further implementation of CBE programs in preparing nurses and midwives will enhance their competences and the quality of health care service delivery.

Study limitations

The study investigated perception of professionals on the appropriateness of the CBE curriculum content in training nurses and midwives in Uganda. In particular, the study was limited to the curriculum organization, clarity of content, and its relevance and suitability. Investigations into other aspects like pedagogical practices used, assessment strategies etc. will give more information to improve CBE training of nurses and midwives.

Implication of the findings on nursing and midwifery training

Gaining knowledge of the appropriateness of the curriculum content within particular contexts could help in improving health care education and practice. From the professionals’ perspective as depicted in this study, there is need for orientating and sensitizing all stakeholders for effective CBE curriculum content adoption. This should in turn lead to proper CBE implementation. Additionally, a curriculum review could reveal the gaps and other areas of concern identified in the current CBE curriculum content. Improving the conditions in the clinical placement sites as well as balancing the time spent in the classroom will go a long way in improving the quality of preparing competent nurses and midwives in Uganda. Furthermore, there is need to investigate the attitudes of students in light of the challenges they face during clinical practicums to unveil the underlying reasons for skipping/dodging clinical learning which is yet a vital component of the preparation of healthcare professionals. The need for recruitment of sufficient numbers of tutors and clinical supervisors to follow and support students during clinical practice is equally vital.

The objective of this study was to examine the appropriateness of the CBE curriculum content of training programs for nurses and midwives in Uganda. The perception of professionals regarding the curriculumcontent appropriateness was conceptualized in four parameters namely; content organization, clarity, relevancy and suitability. The study concludes that the curriculum content used in the implementation of the CBE training program of nurses and midwives achieved the intended goal of preparing skilled professionals who could offer quality health care services. Findings from the perception of the professionals showed that the curriculum content was appropriate for imparting the expected competences i.e. attitudes, skills and knowhow. However, the study recommends that adequate and continuous support of graduate CBE trained nurses and midwives through follow up and supervised clinical practice was found to be necessary for attainment of quality clinical practice. Additionally, standardization of the CBE training programs and sensitization of all stakeholders would ensure proper implementation. This will bring them on board with the new developments of learner-centered training approaches, as opposed to the traditional didactic teacher-centered training approaches they are familiar with.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

Special thanks to our respondents and research assistants for the commitment during data collection.

REFERENCES

|

Adib-Hajbaghery M (2013). Nurses role in the community. Nurs. Midwifery Stud. 2(2):169-170.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Anthopoulou K, Valkanos E, Fragkoulis I (2017). The Professional Development of Adult Educators: The Case of the Lifelong Learning Centres (L.L.C) in the Prefecture of Evros, Greece. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 16(11):77-91.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Arafeh S (2016). Curriculum mapping in higher education: a case study and proposed content scope and sequence mapping tool. J. Further Higher Educ. 40(5):585-611.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Barksdale JD, Newhouse R, Miller AJ (2014). The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI): Information for academic nursing. Nurs. Outlook 62(3):192-200.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Billett S (2016). Learning through health care work: Premises, contributions and practices. Med. Educ. 50(1):124-131.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Botma Y (2014). Implications of accreditation criteria when transforming a traditional nursing curriculum to a competency-based curriculum. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 1:23-28.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Boyd VA, Whitehead CR, Thille P, Ginsburg S, Brydges R, Kuper A (2018). Competencyâ€based medical education: the discourse of infallibility. Med. Educ. 52(1):45-57.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Carraccio C, Wolfsthal SD, Englander R, Ferentz K, Martin C (2002). Shifting paradigms: from Flexner to competencies. Acad. Med. 77(5):361-367.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dlamini CP, Mtshali NG, Dlamini CH, Mahanya S, Shabangu T, Tsabedze Z (2014). New graduates' readiness for practice in Swaziland: An exploration of stakeholders' perspectives. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 4(5):148.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Eraut M (1994). Developing professional knowledge and competence: Psychology Press. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Feldman J, McPhee D (2007). The science of learning and the art of teaching. Clifton Park, NY: Thomson Delmar Learning.

|

|

|

|

|

Flanagan J, Baldwin S, Clarke D (2000). Workâ€based learning as a means of developing and assessing nursing competence. J. Clin. Nurs. 9(3)360-368.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, Holmboe ES, Carraccio C, Swing SR, Harris P, Glasgow NJ, Campbell C, Dath D, Harden RM (2010). Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med. Teach. 32(8):638-645.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, Cohen J, Crisp N, Evans T, Fineberg H, Garcia P, Ke Y, Kelley P, Kistnasamy B (2010). Health Professionals for a new century: transforming education to stengthen Health systems in an independent world. Lancet 376(9756):1923-1958.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Glasgow N, Butler J, Gear A, Lyons S, Rubiano D (2017). Using competency-based education to equip the primary health care workforce to manage chronic disease. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Gruppen LD, Mangrulkar RS, Kolars JC (2010). Competency–Based Education in the Health Professions: implications for Improving Global Health. Commission on Education of Health Professionals for the 21st Century Working Paper.

|

|

|

|

|

Home and Community Care (HCCA) (2012). Competency Based Training and Assessment: Home and Community Care (HCCA) community care worker human resource kit 2007.

|

|

|

|

|

Jephcote M, Salisbury J (2009). Further education teachers' accounts of their professional identities. Teach. Teach. Educ. 25(7):966-972.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Josephsen J (2014). Critically reflexive theory: a proposal for nursing education. Adv. Nurs. 2014:1-10.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kadri MR, Wilson DR, Schweickardt JC, Linn JG, Farias LNG, Moreira A, Lima RT (2017). The Igarau fluvial mobile clinic: Lessons learned while implementing an innovative primary care approach in Rural Amazonia, Brazil. Int. J. Nurs. Midwifery 9(4):41-45.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kiguli J, Ekirapa-Kiracho E, Okui O, Mutebi A, MacGregor H, Pariyo GW (2009). Increasing access to quality health care for the poor: Community perceptions on quality care in Uganda. Patient Prefer. Adherence 3:77-85.

|

|

|

|

|

Komba SC, Mwandaji M (2015). Reflections on the implementation of competence based curriculum in tanzanian secondary schools. J. Educ. Learn. 4(2):73.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

LaLiberte T, Hewitt A (2007). The Importance of Competency- Based training for direct support Professionals. Impact: Feature Issue on Direct Support Workforce Development, Fall/Winter 2007/08. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, Institute on Community Integration (UCEDD). Research and Training Center on Community Living 20(2): 12-13 Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Lunenburg FC (2011). Key components of a curriculum plan: Objectives, content, and learning experiences. Schooling 2(1):1-4.

|

|

|

|

|

McCann TV, Clark E (2003). Grounded theory in nursing research: Part 3-Application. Nurse Researcher 11(2):29.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Medina MS (2017). Does competency-based education have a role in academic pharmacy in the United States? Pharmacy 5(1):13.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ministry of Health (2007). Uganda Human Resource for Health Strategic Plan 2005-2020: Responding to Health sector Strategic Plan and Operationalizing the HRH Policy.

|

|

|

|

|

Ministry of Education and Sports (MoES) (2012). Skilling Uganda; BTVET strategic plan 2012/13 to 2021/2. Kamplala: Ministry of Education and sports.

|

|

|

|

|

Muraraneza C, Mtshali GN (2018). Conceptualization of competency based curricula in pre-service nursing and midwifery education: A grounded theory approach. Nurse Educ. Pract. 28:175-181.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Muraraneza C, Mtshali NG, Mukamana D (2017). Issues and challenges of curriculum reform to competencyâ€based curricula in Africa: A metaâ€synthesis. Nurs. Health Sci. 19(1):5-12.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Norton RE (1987). Competency-based education and training: a humanistic and realistic approach to technical and vocational instruction. Paper presented at the Regional Workshop on Technical/Vocational Teacher Training in Chiba City, Japan. ERIC: ED.

|

|

|

|

|

NVSC (2002). 10 Competency Based training Principles.

|

|

|

|

|

Pijl-Zieber EM, Barton S, Konkin J, Awosoga O, Caine V (2014). Competence and competency-based nursing education: finding our way through the issues. Nurse Educ. Today 34(5):676-678.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Redman RW, Lenburg CB, Walker PH (1999). Competency assessment: Methods for development and implementation in nursing education. Online J. Issues Nurs. 4(2):1-7.

|

|

|

|

|

Sargeant J, Wong BM, Campbell CM (2018). CPD of the future: a partnership between quality improvement and competencyâ€based education. Med. Educ. 52(1):125-135.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Thanh PTH (2010). Implementing a student-centred learning approach at Vietnamese higher education institutions: Barriers under layers of Casual Layered Analysis (CLA). J. Futures Stud. 15(1):21-38.

|

|

|

|

|

Tilley DS, Allen P, Collins C, Bridges RA, Francis P, Green A (2007). Promoting clinical competence: Using scaffolded instruction for practice-based learning. J. Prof. Nurs. 23(5):285-289.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Uys LR, Gwele NS (2005). Curriculum Development in Nursing. Process and Innovation. Newyork: Routledge.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Van Melle E, Gruppen L, Holmboe ES, Flynn L, Oandasan I, Frank JR (2017). Using Contribution Analysis to Evaluate Competency-Based Medical Education Programs: It's All About Rigor in Thinking. Acad. Med. 92(6):752-758.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Wall P, Andrus P, Morrison P (2014). Bridging the theory practice gap through clinical simulations in a nursing under-graduate degree program in Australia. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 8(1):1-10.

|

|

|

|

|

Wesselink R, Lans T, Mulder M, Biemans H (2003). Competence- Based Education. An example from Vocational Practice. Paper presented at the European Conference on Educational research.

|

|

|

|

|

World Health Organization (WHO) (2009). Nursing and Midwifery Human resources for Health : Global standards for the Initial Educaion of professional Nurses and Midwives. Available at: View

|

|