Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

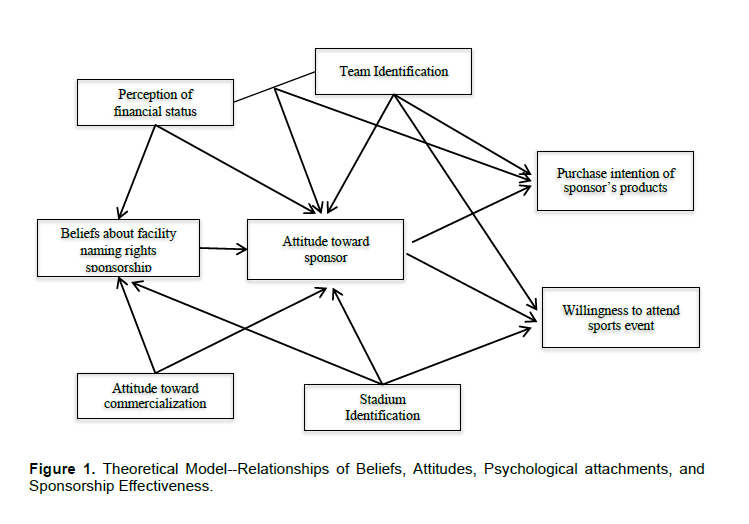

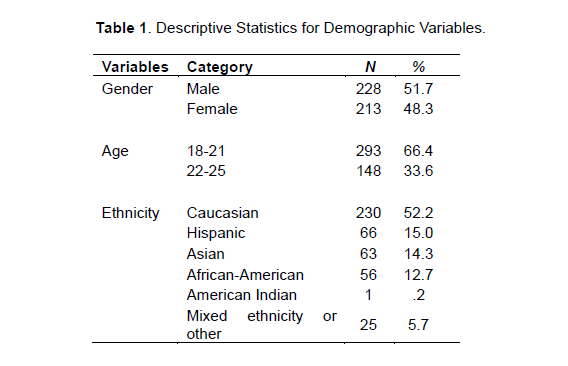

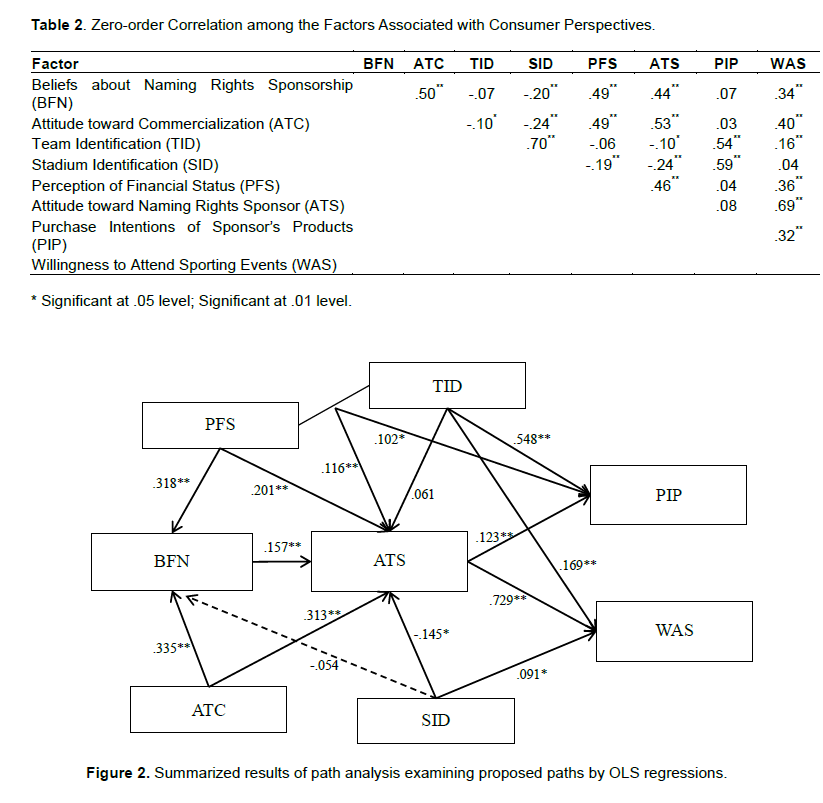

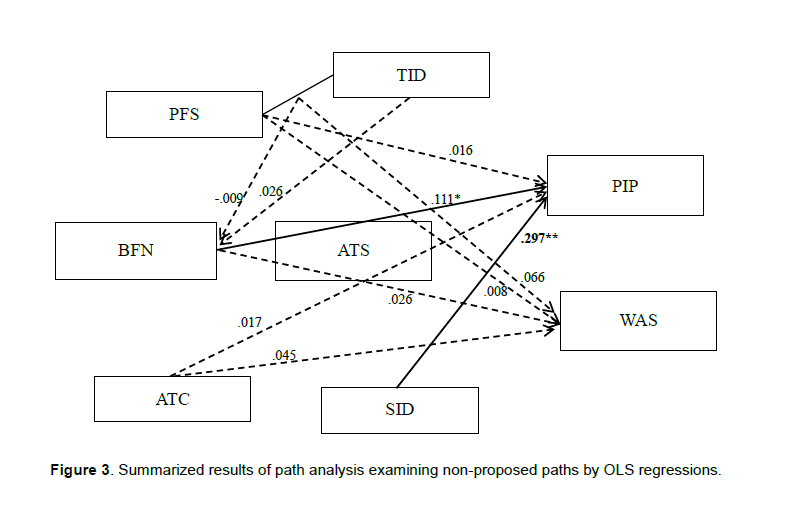

Intercollegiate naming right sponsorship has a great potential in its market value, but it is usually accompanied with a potential risk of generating negative outcomes. With such a dilemma, a structural model that can help in assessing the effectiveness of the sponsorship become extremely important. The current study was designed to reexamine the theoretical framework of a model that was developed for evaluating the effectiveness of naming right sponsorships. Through a comprehensive literature review, the current study identified specific relationships among eight proposed factors, proposed and tested a new structural model through a path analysis. The proposed model fit the data well (χ 2 (1, N = 548) = 42.03, p = .000), where root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .072 with the 90% confidence interval from .050 to .095, comparative fit index (CFI) = .974, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = .025. Most of the hypothesized paths in the model were confirmed, in which attitudes toward commercialization (ATS) are fully mediating the relationship between beliefs about naming rights sponsorship (BFN) and two outcome variables (purchase intention of sponsor’s product (PIP) and willingness to attend sporting events (WAS)). The moderating effects of the two proposed moderators were also confirmed.

Key words: Collegiate Athletics, Facility, Perception, Attitude, Behavioral Intentions

Abbreviation: BFN, Beliefs about the nature of facility naming rights sponsorship; ATC, attitudes toward commercialization; TID, team identifications; SID, stadium identifications; PFS, perceptions of financial status; ATS, regarding attitude toward sponsor; PIP, purchase intention of sponsor’s product; WAS, willingness to attend sporting events.INTRODUCTION

METHODS

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

Before becoming widely adopted as a commercial approach in marketing strategies, sponsorship was lack of apparent borderline with philanthropy donations (Meenaghan, 2001). Corporations that sponsor sporting events are generally motivated by personal interest rather than profitable business objectives (Crompton, 2004). Today, sponsorship has become a widely-adopted approach for sport marketing and continues to grow dramatically in its importance within a corporation’s overall marketing strategies. Kolah (2005) forecasted that the investment in sports sponsorship would grow at an even faster pace considering that sports are reaching ever larger audiences. Along with the growth of sport sponsorship, there are two notable trends that have grown dramatically fast: (a) investment in facility naming rights and (b) investment in intercollegiate athletics. Selling facilities naming rights is fast occurring on a global scale after major sport facilities were identified as a consistent source of long-term income for a professional sport franchise (McCarthy and Irwin, 1998). A record of 44 companies committed more than $1.1 billion in naming rights in 2006 (Show, 2006).

In such a partnership, the venue can earn the payment to keep up pace with escalating player salaries and in the meantime, the businesses can obtain the needed exposure and marketing opportunity (Clark et al., 2002; Thornburg, 2003). Crompton and Howard (2003) predicted that naming rights sponsorship of sport facilities would become more widespread. By 2006, over 70% of the 122 major league professional sport franchises had their home stadia or arenas named after corporate sponsors, which accumulatively accounted for $5 billion in annual revenue. However, only 38 higher education institutions had their facilities named after corporations at the same time period, with accumulative $306 million revenue among the institutions (Show, 2006). Apparently, a potential exists and is also needed for this number to grow when considering the increase rate of expenses in collegiate athletics has been approximately three times the rate of growth of general university budget in the past decade (Wolverton, 2007; Greenberg, 2008). Many internal and external factors, such as facility expansion projects, winning pressures from alumni, and compliance of Title IX, have significantly increased financial demands within college athletic departments. In fact, many collegiate athletics programs are facing financial difficulties; for instance, 84% of institutions in the Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) reported budget deficit in 2006. Collegiate athletic directors constantly face challenges in finding the necessary fiscal resources to adequately support their programs (Fulks, 2011). These financial needs have forced athletic directors to look for corporate supports and seek more sponsorship, possibly including sales of facility naming rights.

However, collegiate athletics is widely viewed as one of the last amateur sport competition in the United States. Although, the number and value of sponsorship agreements have increased, there has always been resistance among various stakeholders within institutions, such as faculty and students, worrying about over commercialization on university campuses (Benford, 2007; Jensen and Butler, 2007). There are also many issues about stadium naming rights sponsorship that have been debated since early 1990s (Boyd, 2000; Chen and Stone, 2002; McCarthy and Irwin, 1998; Moorman, 2002). Boyd (2000) explained that stadium names in the United States usually conveyed a sense of the institution’s history, recognition, and nostalgia. When a corporation places its name on a stadium, however, the only sent message is that the firm paid a lot of money for the right. Several cases provide instances in which a stadium naming rights agreement created a public relations liability. For example, in San Francisco, fans protested against the city government and the football franchise after the name of the historic Candlestick Park was sold to 3Com (Crompton and Howard, 2003; Siebert and Brovsky, 2001). Although, these types of concerns do not always stop the trend of naming rights sponsorships, they may still cause certain negative impact for both sponsors and sponsees. Thus, it is extremely important for corporations and college administrators to comprehensively understand how stakeholders perceive corporate naming deals and how they respond to these sponsorships. Furthermore, although the effectiveness of sponsorship is generally acknowledged, academic research in the area of facility naming rights is still lacking. There is an inadequate understanding about the theoretical and practical mechanism of sponsorship effectiveness (Cornwell and Maignan, 1998; Speed and Thompson, 2000). Sponsors need more empirical evidence to guide their decisions about whether and how facility naming rights as a form of sponsorship is functioning in meeting the marketing objectives of the corporations.

The goal of the current study was to re-examine the relationships among factors in the naming right sponsorship effectiveness model proposed by Chen and Zhang (2011, 2012).Through a comprehensive literature review, we identify a structural model that indicates specific relationships with clear directions among all the factors. More importantly, the proposed relationships that were confirmed in the current study include two mediating effects (from BFN and ATS) and one moderating effect (from PFS). These are very specific effects that were not addressed in previous studies in related fields. While some of the proposed variables and their relationships were discussed in previous studies (See Chen and Zhang (2011) for more discussions), most of them actually have never been examined together before. Thus, the current study contributes to the sponsorship literature by proposing and examining a new structural model related to the effectiveness of naming right sponsorship. By conducting a path analysis to test the proposed model, findings in this study greatly improve our understanding of more specific relationships among critical variables in predicting effectiveness of naming right sponsorship.

When providing sponsorship through facility naming rights, corporations usually attempt to establish marketing connections with fans of collegiate sports. They certainly hope that the favorable associations held by fans toward the athletic programs would be transferred to their brands, which in turn increase their product sales (Madrigal, 2001; Dees, Bennett, and Villegas, 2008). On the other hand, athletic departments need corporate financial support for the rising costs in running a strong program. A facility naming rights can have a huge potential of benefiting both sides of sponsor and sponsee, and can also cause concerns that may potentially generate negative impacts for both sides of the entities in the areas of commercialization, amateurism, and psychological attachment with the stadium. For sponsors who invest millions of dollars on a stadium, it is meaningful to know how these possible negative attitudes of key stakeholders could impact the effectiveness of sponsorship. As higher education institutions are often scrutinized elaborately with highest moral standards, negative perceptions in the minds of the public could lead to reduced donations, endowments, student applications, and student and alumnus identifications. Apparently, to name or not name a collegiate sport facility is a dilemma for corporations and also collegiate athletic programs. Investigating consumer reactions before executing a proposed facility naming plan can help identify the possible negative attributes and formulate strategies to avoid unfavorable consequences for both sides of the entities (Dean, 2002).

Intercollegiate athletics has been considered as a good sponsorship avenue to build and enhance brand image of sponsors (Madrigal, 2000). However, this relatively new sponsorship venture, intercollegiate athletics, has been laden with potentially negative side effects (Zhang et al., 2005). A number of studies have been conducted to measure sponsorship effectiveness in collegiate athletic settings (Dees et al., 2008; Gray, 1996; Gwinner and Swanson, 2003; Kuzma et al., 2003; Madrigal, 2000, 2001; Zhang et al., 2005). While many of these studies reported positive effect of collegiate sport sponsorships on attitude towards product brands (Dees et al., 2008; Gwinner and Swanson, 2003) and purchase intentions (Dees et al., 2008; Madrigal, 2001), some have noticed negative impacts (Kuzma et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2005). Of studies related to sponsorship effectiveness, only two focused on facility naming rights sponsorships and both of these studies focused on professional sport stadiums. Different findings were revealed in these studies: Clark et al. (2003) found a significant increase in stock price due to the facility naming rights and Becker-Olsen (2003) did not. No similar study has been found that examined collegiate facility naming rights sponsorship. Because of the unique market environment associated with higher education institutions, it is necessary to study corporate naming rights in collegiate settings.

One of the major differences between sponsorship and advertising in consumers’ perceptions is the existence of goodwill associated with sport sponsorship (Meenaghan, 1991; McDonald, 1991). Even so, consumers may still hold some negative beliefs and attitudes toward commercial sponsorship activities at times (Alexandris et al., 2007). In the situation of college stadium naming rights sponsorship, a student may hold the belief that financial gain from the naming rights of a facility is an important revenue source for building a strong athletic program and support the mission of a higher education institution. This belief would associate the sponsorship with a favorable attribute. Conversely, a negative belief may exist, leading to unfavorable disposition. How these beliefs construct the person’s attitude toward the naming rights partnership and how these attitudes further influence consumers’ behavior intention should be examined. Conducting a study in the intercollegiate athletic setting, Zhang et al. (2005) examined the effects of college students’ attitudes toward commercialization and the sequential influence on their purchasing intentions of products supplied by the sponsors. Findings of the study revealed that students’ attitudes toward commercialization positively explained 12% of the variance in purchasing intentions. The researchers indicated the need of conducting further studies that would include various types of sponsorship activities and also address concerns related to amateurism in intercollegiate athletics.

Communicating with target audiences through the vehicle of sports instead of direct communication is another difference between sponsorship and other commercial advertisement activities (Meenaghan, 1996). When fans have stronger attachment toward a sport team or athlete, the effect of balanced tendency on the change of their attitudes toward sponsorships would be strengthened (Dalakas and Levin, 2005; Madrigal, 2001). One of the most well documented forms of psychological attachments in sponsorship studies is team identification (Cornwell et al., 2005; Dees et al., 2008; Gwinner and Swanson, 2003; Madrigal, 2001; Zhang et al., 2005). Team identification was defined as one’s level of attachment to a particular sport team (Wann and Barnscombe, 1993). Researchers usually agree that team identification plays a significant role in consumers’ relationship with sports (Laverie and Arnett, 2000; Pease and Zhang, 2001; Sutton et al., 1997; Trail et al., 2003; Trail and James, 2001; Wann and Branscombe, 1993; Wann and Robinson, 2002).

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

ABBREVIATIONS

REFERENCES

|

Alexandris K, Tsaousi E, James J (2007). Predicting sponsorship outcomes from attitudinal constructs: The case of a professional basketball event. Sport Market. Quart. 16(3):130-139. |

|

|

Becker-Olsen K (2003). Questioning the name game: An event study analysis of stadium naming rights sponsorship announcements. Int. J. Sport Market. Spon. 5(3):181-192. |

|

|

Bello D, Leung K, Radebaugh L, Tung RL, van Witteloostuijn A (2009). From the Editors: Student samples in international business research. J. Int. Bus Stud. 40:361-364. |

|

|

Benford RD (2007). The college sports reform movement: Reframing the "edutainment" industry. Soc Quart. 48:1-28. |

|

|

Boyd J (2000). Selling home: Corporate stadium names and the destruction of commemoration. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 28: 330-346. |

|

|

Chen KK, Zhang JJ (2011). Examining consumer attributes associated with collegiate athletic facility naming rights sponsorship: Development of a theoretical framework. Sport Manage Rev. 14(2):103-116. |

|

|

Chen KK, Zhang JJ (2012). To name it or not name it: Consumer perspectives on facility naming rights sponsorship in Collegiate Athletics. J. Issues Intercollegiate Athl. 5:119-148. |

|

|

Chen A, Stone A (2002). The Moniker Morass. Sports Illustrated. 4:96. |

|

|

Cianfrone BA, Zhang JJ (2006). Differential effects of television commercials, athlete endorsements, and event sponsorships during a televised action sports event. J. Sport Manage. 20:321-343. |

|

|

Clark J, Cornwell T, Pruitt S (2002). Corporate stadium sponsorships, signaling theory, agency conflicts, and shareholder wealth. J. Advertising Res. 42(6):16-32. |

|

|

Condotta B (2011). Got $50 million? It could be (your name here) field at husky stadium. The Seattle Times. |

|

|

Cornwell TB, Maignan I (1998). An international review of sponsorship research. J. Advertising 27:1-21. |

|

|

Cornwell TB, Weeks CS, Roy DP (2005). Sponsorship-linked marketing: Opening the black box. J. Advertising, 34(2):21-42. |

|

|

Crompton J (2004). Conceptualization and alternate operationalizations of the measurement of sponsorship effectiveness in sport. Leisure Stud. 3:267-281. |

|

|

Crompton J, Howard D (2003). The American experience with facility naming rights: Opportunities for English professional football teams. Manage Leisure. 8:212-226. |

|

|

Dalakas V, Levin AM (2005). The balance theory domino: How sponsorships may elicit negative consumer attitudes. Adv Consum. Res. 32: 91-97. |

|

|

Dean DH (2002). Associating the corporation with a charitable event through sponsorship: Measuring the effects on corporate community relations. J. Advertising 16(4):77-87. |

|

|

Dees W, Bennett G, Villegas J. (2008). Measuring the effectiveness of sponsorship of an elite intercollegiate football program. Sport Market. Quart. 17(2): 79-89. |

|

|

Eagly AH, Chaiken S (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. |

|

|

Eichelberger C (2008). Rutgers wants $2 million a year for naming rights of stadium. Bloomberg News. |

|

|

EXSS IMPACT (2016). Predicting the value of naming rights for college sport stadia. EXSS IMPACT. |

|

|

Fulks D (2011). 2004-10 NCAA revenues and expenses of Divisions I intercollegiate athletic programs report. Indianapolis, IN: National Collegiate Athletic Association. |

|

|

Gray DP (1996). Sponsorship on campus. Sport Market. Quart. 5(2):29-34. |

|

|

Greenberg M (2008). College athletics-Chasing the big bucks. For the Record. 19(2):6-10. Retrieved November 3, 2008, from SPORTDiscus with Full Text database. |

|

|

Gwinner KP, Swanson SR (2003). A model of fan identification: Antecedents and sponsorship outcomes. J. Serv. Market. 17:275-294. |

|

|

Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equation Model, 6(1):1-55. |

|

|

James LR, Mulaik SA, Brett JM (1982). Causal analysis: Assumptions, models and data. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. |

|

|

Jensen R, Butler B (2007). Is sport becoming too commercialised? The Houston Astros' public relations crisis. Int J. Sports Market. Sponsorship pp. 23-32. |

|

|

King B (2005). Race for Recruits. Sports Bus. J. 8(31):19-25. |

|

|

Kline RB (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. (3rd edition). NY: The Guilford Press. |

|

|

Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics (2010). Restoring the balance: Dollars, values, and the future of college sports. Miami, FL: John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. |

|

|

Kolah A (2005). Sport sponsorship. Sports Busi Int; London. |

|

|

Kuzma JR, Veltri FR, Kuzma AT, Miller JJ (2003). Negative corporate sponsor information: The impact on consumer attitudes and purchase intentions. Int. Sport J. 7(2):140-147. |

|

|

Lance CE (1988). Residual centering, exploratory and confirmatory moderator analysis, and decomposition of effects in path models containing interactions. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 12:163-175. |

|

|

Laverie DA, Arnett DB (2000). Factors affecting fan attendance: The influence of identity salience and satisfaction. J. Leisure Res. 32:225-246. |

|

|

Lee M, Sandler DM, Shani D (1997). Attitudinal constructs towards sponsorship: Scale development using three global sporting events. Int Market. Rev. 14(3):159-169. |

|

|

Madrigal R (2000). The influence of social alliances with sports teams on intentions to purchase corporate sponsors' products. J. Advertising 29(4):13-24. |

|

|

Madrigal R (2001). Social identity effects in a belief-attitude-intentions hierarchy: Implications for corporate sponsorship. Psychol. Marketing 18(2):145-65. |

|

|

McCarthy L, Irwin R (1998). Names in lights: Corporate purchase of sport facility naming rights. Cyber J. Sports Market. 2: 1-10. |

|

|

McDonald C (1991). Sponsorship and the image of the sponsor. Euro. J. Market. 25:31-38. |

|

|

Meenaghan T (1991). The role of sponsorship in the marketing communications mix. Int. J. Advertising 10(1):35-47. |

|

|

Meenaghan T (1996). Ambush marketing - A threat to corporate sponsorship. Sloan Manage Rev. 38:103-113. |

|

|

Meenaghan T (2001). Understanding sponsorship effects. Psychol. Market. 18(2):95-122. |

|

|

Moorman A (2002). Naming rights agreements: Dream deal or nightmare? Sport Marketing Quart. 11:126-127. |

|

|

Pease DG, Zhang JJ (2001). Socio-motivational factors affecting spectator attendance at professional basketball games. International J. Sport Manage. 2(1):31-59. |

|

|

Shelton S (2006). Got sports? Today, Sports marketing is a 'field of dreams'. Business Tech Associates. |

|

|

Show J (2006). Finding the hot spot. Sports Bus J. 14-19. |

|

|

Siebert T, Brovsky C (2001). Lawsuit over Denver stadium name unlikely. The Denver Post, 2. |

|

|

Speed R, Thompson P (2000). Determinants of sports sponsorship response. J. Acad Market. Sci. 28(2):226-238. |

|

|

Sutton WA, McDonald MA, Milne GR, Cimperman J (1997). Creating and fostering fan identification in professional sports. Sport Market. Quart. 6(1):15-22. |

|

|

Thornburg RH (2003). Stadium naming rights: An assessment of the contract and trademark issues inherent to both professional and collegiate stadiums. Virginia Sports Entertain Law J. 2(2):328-358. |

|

|

Trail GT, Fink JS, Anderson DF (2003). Sport spectator consumption behavior. Sport Market. Quart, 12:8-17. |

|

|

Trail GT, James J (2001). The Motivation Scale for Sport Consumption: Assessment of the scale's psychometric properties. J. Sport Behav. 24:108-127. |

|

|

Wann DL, Branscombe NR (1993). Sports fans: Measuring degree of identification with their team. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 24:1-17. |

|

|

Wann DL, Robinson III TN (2002). The relationship between sport team identification and integration into and perceptions of a university. Int. Sports J. 6(1):36-44. |

|

|

Wolf BD (2007). The name game: Company banners flying on more college stadium, arenas. The Columbus Dispatch. |

|

|

Wolverton, B. (2007). Growth in sports gifts may mean fewer academic donations. The Chronicle of Higher Edu. 54(6), A1 (Section: Athletics). Retrieved November 3, 2008, from http://chronicle.com |

|

|

Zhang Z, Won D, Pastore DL (2005). The effects of attitudes toward commercialization on college students' purchasing intentions of sponsors' products. Sport Market. Quart. 14(3):177-187. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0