The overarching aim of this paper is to examine empirical findings on the arena of consumers’ behavior and attitude towards intake of street-foods (SFs) and fast foods (FFs) status as well as associated risks of consumption in China. Presently, consuming SFs and FFs have become a popular trend and is counted as the manifestation of modernity in most fast growing countries, for instance, China. The SFs and FFs are believed to be a panacea to the major socio-economic problems for countries having a large population. Over one-quarter of the century FFs and SFs become rapidly expanded in China through the quick service provision of already prepared foods with reasonable prices and source of employment for swarming open country and city inhabitants end to end to its supply. FFs and SFs are the most preferred by consumers because of safety issue, reasonable price, ready-made nature, easily accessible, portability, and so on. Concurrently, the nutritional and health concerns in China revealed that the government is very committed to quarantine and certifies FFs and SFs of food safety and public health, particularly after melamine was detected in milk in the year 2008. This later stimulated the Chinese regime to put into practice food safety law (FSL) in 2009 next to food hygiene law (FHL). FFs and SFs consumers in China are very conscious of food quality and give credit for safety than purchasing prices. Broadly speaking, most examined the papers indulged that FF and SF choice rely on ‘safety first’ by consumers in China. To sustain vendors stock and satisfy consumers’ demand for SF and FF, avoiding health risks, change in the existing perception and trust building is a priority issue.

To date, China has been found to have transitional economic development strand with “leapfrog” economic growth and high population growth. With increasing population number, the demand for food and the cost of production also increased for country like China. The safety of food consumed everyday has become the focal point for various concerned groups, particularly for Chinese people, it is quite valuable because they give high weight for food safety (Yan, 2012). Like many countries of the world, there is a rapid shift in the purchasing and consumption of traditional Chinese cuisine to western style FF and SF consumption. Among those changes that has been done, the practical change in peoples food intake from a conventional diet to a westernized diet is a consequence of manifold causes (e.g. feelings of urbanization) (Zhai et al., 2014) that could amplify the known health problems namely, obesity and chronic diseases (Yan, 2012). The FF industry and its consumption consequences like obesity rates have increased rapidly in China in just one-quarter of a century. According to the countrywide information indicated that more than over one-third of Chinese adults are overweight or obese, whereas in big cities like Beijing, more than half are obese (Wang et al., 2007). Western-style fast-food restaurants in many Asian, Latin American and African cities have a long tradition of street food vendors and hawkers (Selling street foods and snack foods, Food and Agricultural Organization. [http://www.fao.org/docrep/015/i2474e/i2474e00.pdf]).

In recent times, the foremost consumption of street foods and fast-foods has become a trend; particularly in peri-urban towns and cities of developing nations, it has been indicated that more consumers are eat more meals outside of homes. In most developing countries, the consumption of food away from home has been growing swiftly (Kaynak et al., 1996; Farzana et al., 2011; Alima, 2016). Previously, SF and FF consumption were less known in South Africa; however, they later became a potential employment sector and vending of food (Mathee et al., 1996). Though it is very difficult to clearly define “street foods” (SF), South Africans found a way to define it as foods or beverages that are sold by the informal sector. The street foods are broadly sold out from stands or corridors on the pavement of busy streets in both urban and rural areas, usually with cheaper price than fast foods (Alima, 2016).

Therefore, both FF and SF are an accessible supply of food to lower economic class. Generally speaking, there is homogeneity in food items and beverages for sale and many vendors sell the same items. For instance, there are some common SF and FF sold in the major cities of China. SFs sold in major Cities of China, include snacks such as crisps (Chinese Jianbing), Jiaozi (Chinese dumplings), hotpot (Chinese Huo guo), rou jia (Chinese Humberger), Chinese style fried chicken, Banuian (Chinese noodle soup), Baozi (Chinese bread buns), etc. and only soft drinks; however, cooked foods are also sold, frequently on site (Shanghai street, 2017). On the other hand, FFs are sold from outlets in formal structures like buildings and malls and frequently operate as a franchise.

Meanwhile, FFs are the most preferred by consumers because of the timing of food preparation, consumers’ lifestyles and family structures which change as westerns (Choi et al., 2013). Differences exist among consumers across countries, culture, ethnicity and other reasons. For example, a study conducted in Malaysia on students from different ethnic backgrounds ensured that Chinese prefer “food safety”, Malays choice is “halal” and Indians priority is “freshness” of FFs (Farzana et al., 2011). Some are of the opinion that it causes ischemic heart disease (Kirkpatrick et al., 2006); street foods are largely unhygienic (Schlosser, 2001; Smil, 2000; Trafialek et al., 2017); and in Australia, food market promotes unhealthy eating and obesity in children (Dixon et al., 2014).

What is more, consumers have to pay attention to other things such as work which make them forget cooking and shift to consuming FFs from vendors (Schröder and McEachern, 2005; Tiemmek, 2005). Consequently, consumers need for food outside the home has increased, as it saves consumers time and has marginal utility (Farzana et al., 2011). Chinese have become more conscious of food safety after the 2008 poisonous milk attack with melamine and has made the government highly committed to inspection and certification of food safety in harmony with the ratifying food safety law (FSL) enacted in 2009 (Ross, 2012). Unlike the Chinese, the USA consumers are more apt to enacting the ‘‘politics of choice’’ rather than ‘‘politics of loyalty’’ as responsible members of society synonymous with the calibration on the Slow Food movement (Chaudhury and Albinsson, 2015). A study conducted in Thailand indicated that consumers are more likely to prefer street food than restaurants. Correspondingly, a study conducted in Malaysia confirmed that consumers are not price sensitive, but are rather very conscious predominantly of food safety, halal status and freshness. Notwithstanding other studies conducted outside, Chinese consumers pay attention to food safety.

Though FFs and SFs have a strong association with overweight or obesity, their customers have drastically increased throughout the World. Within two to three decades, emphasis has been increasingly placed on quick meal solutions due to the busier consumer lifestyle and dual-working families with children (Atkins and Bowler, 2001).

Fast foods consumption in the globe at a glance

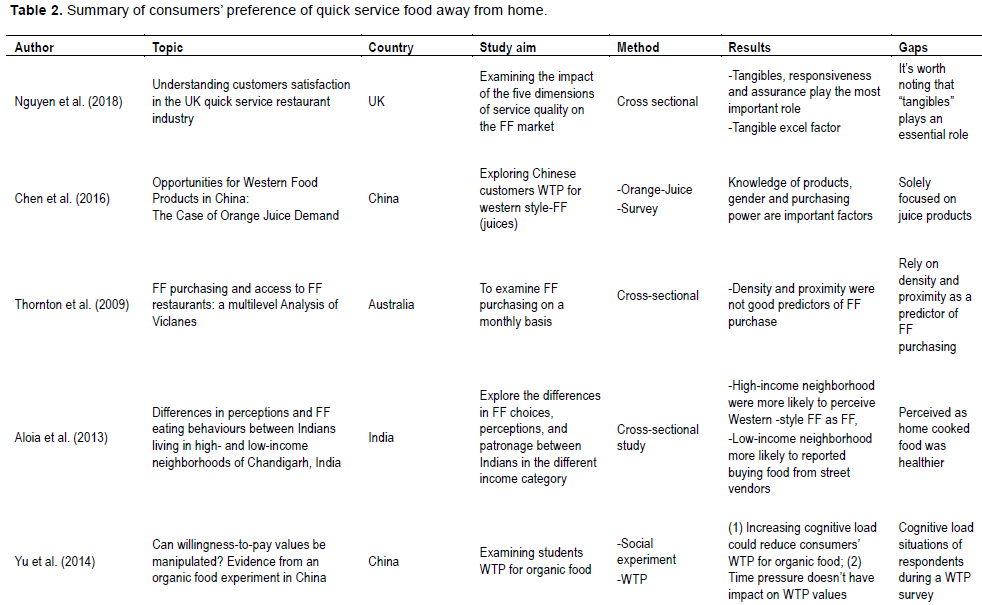

Dozens of examined papers evidenced that the first FF cafeterias were inaugurated in America at White Castle in 19162. Presently, American-founded FF branded chains such as McDonald's, Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) and Pizza Hut are multinational corporations with outlets across the globe3. Likewise, the modern FF industry in China began when the first KFC restaurant opened in Beijing in 1987. This inertia has been caused by many factors such as over-saturation, slowing economy, fade up-modernization, the rise of fast casual restaurants, and obesity.

In countries outside China, which have FF industry, such as Bangladesh, their first launch was at Bailey Road of Dhaka. Later it expanded to many areas of Dhaka city. A critical look at the nature of FF shops, malls, etc, show that they deliver the service in franchise system in Bangladesh (Islam and Ullah, 2010); identically, provision in Malaysia is also in franchise (Farzana et al., 2011).

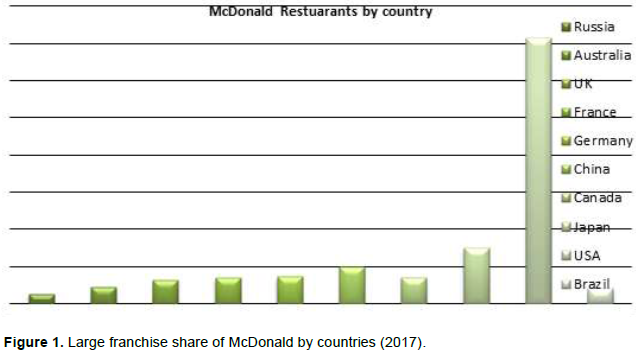

New brands like Swiss, Helvetia etc. are names of some Bangladeshi FF shops formed in franchising system. 13 years later, China and Bangladesh experienced entry of the first international brand of FF franchise in the country. At the time, KFC is perceived as high-quality FF with a popular array of complete meals that enrich the consumer’s everyday life (Islam and Ullah, 2010). Among the American originated and franchised FFs restaurants, McDonald is the second largest in China. The graphic description below shows the top 10 world nations with large share are Russia, Brazil, Australia, UK, France, Canada, Germany, China, Japan and USA from lowest to highest McDonalds FF restaurants’ (Figure 1).

Theories in consumption of fast-food and street-foods

Consumers are very sensitive to what they intend to consume in the food market. As result of the consumer’s behavior on market, emphasis on factors influencing the decision-making process of FF and SF consumption rises. The consumer behavior theory assumes that consumers are rational and perfect. Consumers have adequate knowledge and are fully aware of their needs and desire up to how to satisfy themselves in the best possible way. Studies on Fast-Foods and Street Foods are very limited, especially in nations building a strong economy, like China. Among reviewed papers, street food vending is an important public health issue for all mankind ready to consume (Rane, 2011). Following historically unprecedented urbanization growth and globalization, there has been parallel increase in consumptions of FF and SFs. This study has reviewed the consumer behavior model to analyze consumer perception and attitude towards SF and FF in China. Nevertheless, according to the analytical framework, consumers’ choice and decision making process of FF and SF mostly relies on brand name, labeling, quality, price, healthiness, and associated socio-cultural complex behaviors. This paper has been organized successively. At the very glance, overall food and beverage industries distribution across the globe has been discussed; followed by a brief presentation of consumer theories. The procedures charted to organize, review and to filter out among the horizon of bourgeoning literature is further discussed. Also, FF and SF distribution in China, the factors that influence consumer’s choices of FF and SF, along with health and nutrition dimension of FF and SF is succinctly presented; and lastly, closing remarks pinpointing literature and policy gaps has been indicated.

1. See Marshalian theory of consumer

1. See; 12 street Foods in China; 35 Shanghai street foods

2. See from internet: 12 Chinese Street Foods; 35 Shanghai street foods we can’t resist.

Over 500 papers were collected for this review purpose. Out of the total, approximately 60% are health and nutrition-related findings, about 30% are marketing and economics related findings and the rest are social marketing and behavioral psychology associated results. To this end, the heuristic evidences of this study are organized based on subject matter and findings. Summarily, those previous fast foods and street foods (quick service foods) or food away from home consumption has skyrocketed (Feltham, 1998). From marketing and hospitality perspectives, brand, labeling, price, color and other customer attraction has been given so much attention; whereas from consumers and health seekers point of view, such fast service intake have focused on the nutritional content, healthiness, organic, quality, price and other dimensions important for consumption decision.

The methods employed in this paper include both before and after, as well as trend analysis. Dozens of papers were examined and consulted to analyze the FFs and SF status; however, most papers were written outside the People’s Republic of China and may or may not have revealed the realities in China. Among evaluated papers on consumer’s perception, behaviors and preference of FFs and SFs, most employs a survey method with diverse sampling method and size. The following findings illustrated the increasing interest and attention afforded FFs and SFs by various groups based on consumer’s perception, attitude and safety of street foods and fast-food.

i) For instance, a study on evaluation of roadside diet and quick service diet consumption in South Africa employed a cross-sectional investigation method with structured interview schedule (Steyn et al., 2011).

ii) Analysis of consumers’ preference of fast-foods and influencing factors with 187 sample respondents in Malaysia (Farzana et al., 2011).

iii) FF consumption, dietary condition and community experience of diverse culture and tribe-based FF study of Atherosclerosis (Moore et al., 2009).

iv) Consumers’ perception and attitude regarding imported seafood into the US by six countries using online survey (Wang et al., 2013).

Fast foods and street foods

Farzana et al. (2011) operationally defined FFs as quickly prepared, reasonably priced, and readily available alternatives to home cooked food. Whereas SFs are prepared instant foods available at moderately cheap prices, teeming urban dwellers are attached to street foods because of its gustatory attribute. Though people use FFs and SFs interchangeably, there is a vivid difference between them.

Fast food is an important item for the people as it is readymade in nature and easy to eat (Islam and Ullah, 2010). The compound word FF was first defined as a vocabulary of Merriam–Webster since 1951. According to Merriam–Webster, fast food is the term given to food that can be prepared and served very quickly. The main visible deviation between street foods (SF) and fast food are price, shopping area, packaging, labeling, brand, cooked or uncooked (e.g. fruits) and so on. The FF is the fastest growing food item and are quick, affordable and readily available alternatives to home cooked food (Goyal and Singh, 2007; Islam and Ullah, 2010; Yan, 2012).

Broadly speaking, any meal with low preparation time can be considered as fast food. Nevertheless, it typically refers to the foods sold in a restaurant with low preparation time and served to the customer in a packaged form for take-away. However, street foods are vended between vendors and consumers on the street, such as taxi stations, bus stations, outlets of subway corners, crowded street corridor, at the gateway area of towns and cities and so on. These meals are mostly retailed by small businesspersons. Fast food and street food are mostly convenient and economical for busy lifestyle singles, youths, students, researchers and others.

The commonly known FFs are different from convenient; they are ready-to-eat at the time of travel or walking and collectively include sweet items like cakes, biscuits, breads etc.; breakfast items like potato chips, candies, peas etc; and fruit items. Among the major FF items recognized with brand name are burger, pizza, fried chicken, hamburger and sandwich. Quick Service Restaurants (QSR’s) are the popular name given to FF restaurants and FFs are mostly termed as Food Away From Home (FAFH) (Bowman and Vinyard, 2004; Camillo and Karim, 2014; Islam and Ullah, 2010). There are three major FF restaurants in China, viz; KFC, McDonalds and Yum China (Pizza Hut).

Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC)

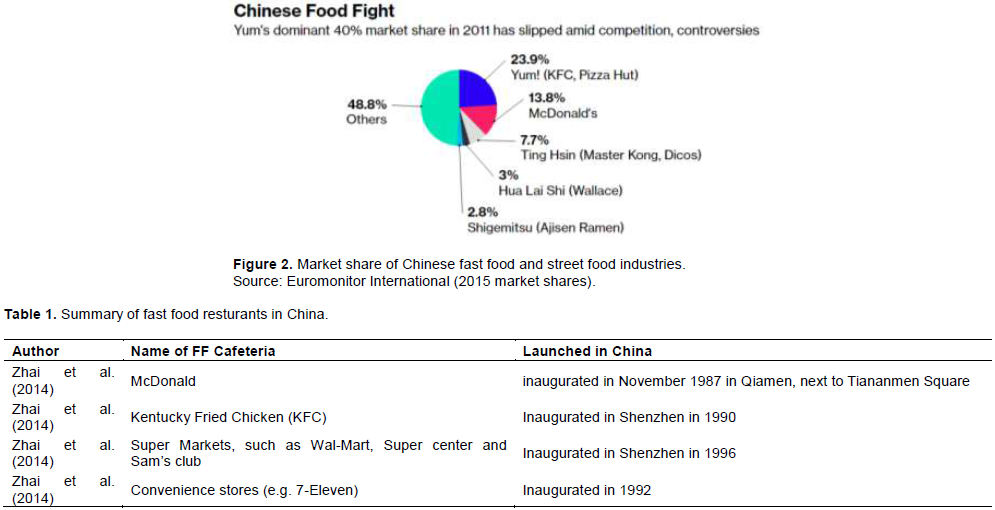

The first FF industry opened in Tiananmen Square in 1987 was KFC. The FF restaurant still had a large market share as compared to McDonalds and Pizza Hut in China’s FF industry history. KFC has got a brand name with “Always Original” and has returned to the basics with clear value at memorable price points and innovation close to the core. One of the most impressive stories of a U.S. multinational in an emerging market is unfolding right now in China. On average every day, KFC is opening one new restaurant (on a base of some 3,300), with the intention of reaching 15,000 outlets (Figure 2)

McDonald's

This FF restaurant first invented in America launched its services at San Bernardino, California in 1948 and later opened a franchise in Qiamen, China in 1990 next to Tiananmen Square, PR China where KFC was already located. McDonalds has the second market share next to KFC (Table 1).

Yum Chain (Yum, Pizza Hut)

The Yum restaurants are third ranked fast foods suppliers in China. As the other FF sources, Yum! Brand restaurants experienced a decline in recent times. Currently, only very little literate magnifies the contribution of FF industries in the Chinese food market.

Overview of food industry in China

Fast food industry in China

For over two decades now, FFs have been undergoing revolution in attracting consumer tastes, promoted by cooking programs, long travel and growing ethnic-cultural diversity in China. The FF industry in China has grown exponentially in a short period. In a similar vein, the threat of FF consumption has been attracting both government and consumers. The risks associated with purchasing FFs include obesity (Wang et al., 2016). The modern FF industry in China started when the first KFC restaurant opened in Beijing in 1987. Over the past twenty years, the industry grew rapidly, due to rapid developments of China’ economy, urbanization, increased family income, shifts in social norms (e.g., shifting from eating at home to more frequently eating out), strong marketing strategies by the FF industry, increased FF service providers, improvements in chain store and franchising management, as well as new brands and food choices. The FF industry had estimated revenues of $94.2 billion in 2013, making up about 20.0% of the total catering sub-sector revenue in China (Wang et al., 2016).

According to a recent report, over 2 million FF restaurants operated in China in 2014, including franchise and chain operators of all sizes and independent Chinese-style FF facilities. The majority of the enterprises were small and independent facilities that engaged in traditional Chinese-style FFs. In recent years, the FF industry revenue grew at an annual rate of about 13.0%. Presently, China has over 2 million fast food facilities that generated 94,218 million US dollar revenue earned in 2013 (Wang et al., 2016). Though FF industry is believed to be a U.S. invention, the “fish-n-chips‟ format has prevailed in the UK since the 18th Century, as an outlet where the working class could easily purchase lower price ready-made meals (Richardson and Aguir, 2003). Food provided by the FF industry includes both Chinese FF and Western FF. Western FF restaurants in China are predominantly from the U.S., for instance, KFC, McDonald's, and Pizza Hut. The number of U.S. FF restaurants has increased dramatically in China.

At present, “Yum! China”, the parent company of KFC, Taco Bell, and Pizza Hut, has approximately 4800 KFCs and 1300 Pizza Huts, with a plan to open 20,000 restaurants in China. McDonald's is expanding in China at a rate of approximately 10 new restaurants each week. This also indicates how American FF culture has influenced consumers in China (Fast Food in China, 2017).

As of 2015, there were 4,600 Kentucky Fried Chicken restaurants in several cities in China. This has risen from 2,100 outlets in 2010 and 1,759 outlets in 2005. Kentucky Fried Chicken was the first Western fast-food chain to arrive in China and remains the most popular restaurant franchise in China. Though the first KFC was opened in 1987, by 1997 it had 100 outlets in 33 cities. In 1999 it had 320, and by 2007, a KFC outlet was being opened at a rate of about one per day. Kentucky Fried Chicken's biggest Chinese competitor is Fast Food Dajiang. China’s FSL was passed on 28 February, 2009 and has taken effect since 1 June, 2009.

This law is formulated to ensure food security and prescribe safety standards of food, regulations on food production, food examination, food imports and exports, along with disposal of contaminated food. In 2011, “Food Safety Standards of Fast-food Service” was issued to regulate the employment, selection of store location, management personnel, equipment preparation, and process control of FF stores. The laws and regulations concerning franchise businesses were initially established in November 1997 when the Ministry of Internal Trade published the first Chinese franchise law tagged Regulation on Commercial Franchise Business. This was initially a trial implementation and included important legal issues such as trademarks, copyrights, and intellectual property protection. Since then, the regulation has been modified and enhanced.

The latest version of the franchise rules, Measures for the Administration of Commercial Franchises, was issued by China’s Ministry of Commerce and became effective in February, 2005. This new regulation replaced the first franchise law and became the only legal framework for franchising in China. However, these laws and regulations were not driven by public health goals.

Reasons why consumers’ prefer fast-foods to restaurants

Consumers’ preferences of fast food are dependent on very strong ties with food-culture in some societies. Although seemingly simple, eating, drinking and food choices are influenced by complex - the most frequent human behaviors (Köster and Mojet, 2016). This is because of the parallel changes in working, social life and the habits of dining out. From a social context, the numbers of working families are gradually increasing worldwide (Stamoulis et al., 2004). The customs today involve socialization with some food items away from home. Due to the shortage of time, many modern nuclear families tend to prefer convenient, quick meals to rather traditional long meals.

The comprehensive picture of a rapidly urbanizing world covers up large regional differences. As a result, urbanization will proceed gradually in many developed and transition countries in the future where the vast majority of the population is already living in urban areas. At the other end of the scale are sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, where urban populations will be growing at an astonishing rate of nearly 5% per year (Stamoulis et al., 2004). All factors mentioned above induce a move away from traditional time-consuming food preparation towards precooked and convenience food at home but also fast food, snacks, and street foods for outside meals.

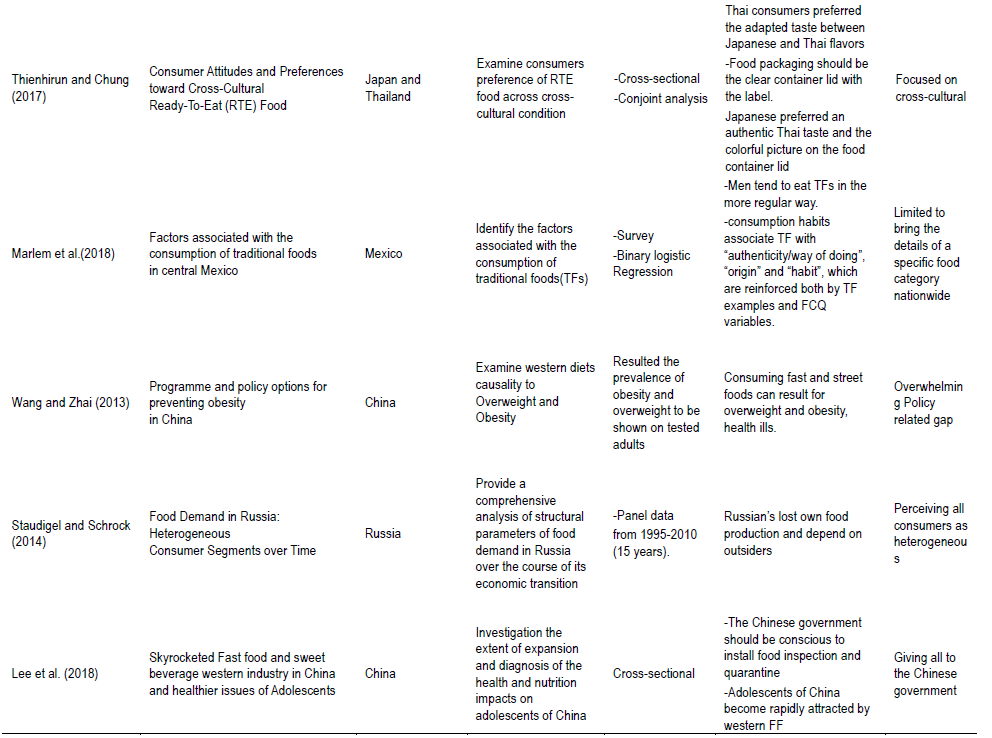

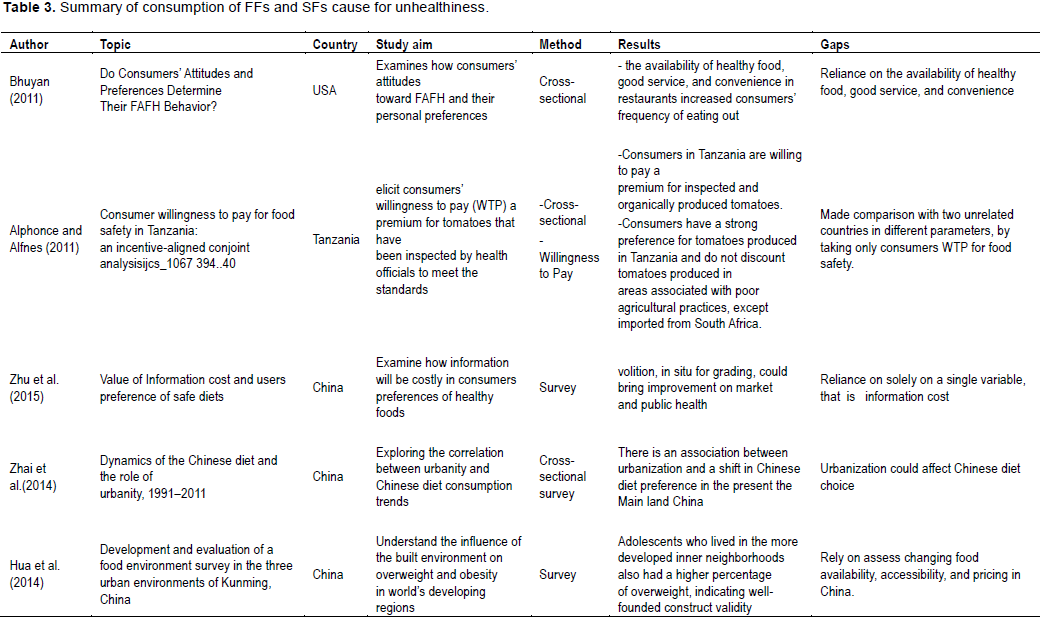

Urban diets are higher in fat, sugar and salt content, respectively; contains higher amounts of meat and dairy products than rural ones, lower amounts of fiber and higher intakes of alcohol (Popkin and Du, 2003). The trend towards FAFH is also strong among the poorest segments of urban populations. The details are summarized in Tables 2 and 3

The factorial analysis of Islam and Ullah (2010) revealed brand name as the most important factor to the FF users among other factors (e.g. nearness accessibility, alike taste of FF, price and class affiliation, price cut and flavor, fresh and sanitation, and so on) that are most preferred to less preferred FFs in Bangladesh, respectively. In South Africa, apart from fruits, other street foods are not recommended to consumers’ by nutritionals professionals; which includes foods not prepared according to the recommended nutrition and dietary menus (Steyn et al., 2011).

Health risks in consumption of fast-foods and street foods

One of the first debates encountered in the literature is that on the existence of objective risk. Bauer (1960) strongly emphasized that he was concerned only with subjective (perceived) risk and not “real world” (objective) risk. Stone and Winter (1985) argues that there is no such thing as an objective risk; except perhaps for physical risk. They believe that it is impossible to have some real world or objective social, psychological, time, and financial and performance risk. The consistency of their argument is broken when they accept a doctor as being an “objective” risk assessor for physical risk, but reject a financial expert as being able to give an objective assessment on financial risk (Mitchell, 1999). More importantly, obesity and unhealthy food consumption are the salient public health issues, particularly in developed nations (Davies and Smith, 2004; Dong and Hu, 2010; Ji and Chen, 2013; Kara et al., 1995; Mcferran et al., 2009).

A recent study in India strengthens the major causes of health risks in FF and SF consumption that pertained specifically to fast food with distinctly “Western-style” characteristics (Dutta et al., 2014). Though FF and SF consumption causes obesity, it is still debatable because by itself, it is not a proper diet and can cause underweight and stunting in infant children. Varieties of fast foods are chosen by girls and young women of African and South Asian countries (Lawrence et al., 2007). Many issues that affect the food choice of people who move to the UK are common within different ethnic groups. Richard and Padilla (2009) study considered only measurable attributes of fast food, viz; nutritional profiles, vendor identity or the distance from a consumer’s home.

A study by Aksoydan (2007) determined food quality to be the most important variable in restaurant choice. The five factors most commonly included in respondents’ rankings were: (1) range of food (2) quality of food (Bhat et al., 2018) (3) price of food (4) atmosphere (Nago et al., 2014), and (5) speed of service (Platania and Privitera, 2006) . Over the past twenty years, obesity has been increasing rapidly in China (Du et al., 2004; Du et al., 2014). National data show that the prevalence of overweight and obesity among adults increased from 20% in 1992 to 30% in 2002 and 42% in 2012 based on the Chinese BMI standard (Wang et al., 2016). This increase paralleled that of FFC. What is more, the consumption of FF is influenced by social values, cultural background, peer pressure, knowledge, and price. Normally, it is said that ‘health is wealth’. Healthy food availability and access is a means of living for everyone. However, due to swiftly skyrocketed FF restaurants in USA, health and eating out have largely shown that eating food away from home adversely impacts an individual’s health, including contributing to obesity (Bellemare et al., 2017; Bhuyan, 2011). In other words, consumers understand that meals and snacks consumed away from home are typically less healthful than foods prepared at home (Anderson et al., 2011; Brown et al., 2000; Lin et al., 1999). Arguably, consumers with a greater desire for a healthful diet should adjust their behavior by abstaining from dining out on a frequent basis, keeping constant other factors (Bhuhan, 2011; Duffey et al., 2007; Li et al., 2010; Lusk and McCuskey, 2018; Moher et al, 2009).

Factors influencing street food and fast foods

According to the study by Farzana et al. (2011), fast-food consumption by students is influenced by three main factors (1) food-safety (2) taste of food, and (3) reputability of preparation. A study conducted underpins food safety with an extraordinary glimpse of the “story of milk” in China. A clever advertising slogan used by the company emphasizes this play on words: "China cow, World cow, Mongolian cow" is also "Awesome in China, Awesome in the world, Awesome in Mongolia". This is an early reminder to Chinese, which make them never compromise on quality matters. Wen Jiabao also spoke of the "quality" of the nation (Rohrer, 2007). He commented that his wish [to increase milk consumption] would strengthen the nation. Here the words used are "minzu shenti suzhi" literally meaning the "quality of the body of the race." This reference to suzhi (quality) is instructive. A study in the UK has considered only measurable attributes of fast food - nutritional profiles, vendor identity or the distance from a consumer’s home (Richard and Padilla, 2009).

The evaluation assured that the above criteria are not working for Malaysians because they give high value and build trust on “halal status, food safety and rapidity of service rendering”. “Halal” is commonly known as Muslim cafeteria, and is perceived as more vital to Muslims customers (Franzana et al., 2011); it is not for Chinese who give high credit to quality and safety rather than trash business ads (Ross, 2012). There are many factors that influence consumers; these includes brand name, labeling, originally, certification, packaging, taste, price, health risks, safety, quality, etc. In summary, consumers’ perception purchasing behavior of FFs and SFs are influenced by many complex factors and differ across cultural and ethnic diversity countries.

1. "China's Free Range Cash Cow," Bloomberg Business Week, 24 November 2005.

http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/05_43/b3956083.htm

2. Rohrer, F., "China Drinks its Milk," BBC News Magazine, 7 August 2007. http://news.bbc.co.uk/

2/hi/6934709.stm, cited in Wiley, A. S., "Milk for 'Growth.'"

1. See the report, KFC radical Approach to China (2017)

2. See the Bloomberg analysis (2017)

3. See Fast foods markets in China