The purpose of this study is to identify and analyze, based on representations of physical education teachers, the obstacles to teaching of cuff volleyball in middle schools in Brazzaville, Congo. The theoretical model of Trinquier’s representations, which is based on the "attitude" variable as an evaluative judgment variable, made it possible to distinguish the attitudes of teachers and to characterize this population in terms of representations, and therefore sociological anchors. A total of 86 physical education teachers responded to a questionnaire, and 18 structured and intensive interviews were carried out. These were addressed using categorical content analysis. Subsequently, classical statistical indices (numbers, percentages, confidence interval), chi-square test and multinomial regression analysis were used to analyze the attitudes observed on teachers. The results show that the lack of time, material and space, the plethora of effectives in classes, the specific perceptions to socio-professional, motivational, ecological and didactic variables, represent pedagogical misunderstandings by hampering the teaching process of this technical gesture. Thus, our data reveal the need to promote new methods of teaching volleyball cuff, contextualized in Negro African environment.

In Congo, Physical Education (PE) is a teaching discipline of the education system. This school discipline uses Physical Activities and Sports (PAS) teaching to develop collectively and individually. Nowadays, team sports are the most popular among schoolchildren. Their teaching interests researchers in the field of Sciences and Techniques of PAS (STPAS) (Gréhaigne, 1992). Formerly used in sports animation to manage the recurring problem of overcrowding pupils of classes in sub-Saharan Africa (Ogueboule, 1999), team sports today have a physical education content to be taught and defined by study grade (Atoun et al., 2018a; INRAP, 2005). The designed curricula give precedence to the pupom, who is immediately placed in core of the construction of his own knowledge (Atoun et al., 2018b). The aim of team sports teaching is two-fold: to train a technically and humanly balanced, efficient citizen; and to contribute to human development (Attiklémè, 2009). With reference to several studies on team sports, their teaching is based on the correct achievement of specific motor skills (Gréhaigne, 1992), focused on the learner and on the game (Poussin et al., 2014; Gréhaigne et al., 1999). Teaching of team sports in physical education, by subscribing to this logic, makes operational

this established purpose of the scholar curricula. Team sports present privileged spaces for the selection and production, as well as transformation and transposition, then transmission of values, knowledge, and skills to school audiences (Backman and Barker, 2020; Klein, 2003 in Attiklemé and Kpazaï, 2011: 84). Among these team sports, volleyball, which is a physical activity of cooperation characterized by opposition of players, was selected. Volleyball teaching serves as a means of intellectual and physical education as well as social integration (Amans-Passaga and Verscheure, 2020; Silva et al., 2020). However, in subsaharan Africa volleyball is scarcely taught because it is a high-performance activity which presents several difficulties in its practice and in its teaching (Atoun et al., 2018a). It is particularly one of the most difficult team sports to teach (Oguéboulé, 1999). This high-stakes game links technical, tactical, physical and mental aspects in a temporal urgency context, imposing speed of reaction and gestural automation. This situation creates constraints which influence the teaching practice of the class grade; its teaching in the middle schools thus remains a problem. Several reasons seem to justify this observation. First, volleyball involves highly technical knowledge of teachers, and two technical dexterity, scientific and professional knowledge (Terrisse, 2001; Lepuissant, 2016). Second, the logistical difficulties and the plethora of class sizes add to the score without forgetting some socio-professional factors (Atoun et al., 2018b). It is therefore in this gloomy context that the teaching of volleyball cuff takes place in middle schools in the Republic of Congo.

Aim of the research

It emerges from our experience as a physical education teacher, from our observations and from the reports of national conferences on the teaching of physical education, that volleyball is hardly practiced in Congo, and it is scarcely taught in the majority of establishments of the interland. The teachers, without well-off in knowledge, higher acquired knowledge and know-how in this practice avoid the teaching of cuff, fundamental technical gesture in the practice of volleyball. In addition, we note the existence of the perception of "legitimate" competence (Bourdieu, 1980) among Congolese teachers of physical education. In other words, there appears to be a potential insufficiency in the recognition of “statutory competence” (Bourdieu, 2006) in the implementation of volleyball lessons focused on cuff’s teaching in schools, especially in middle school where this sport is taught for the first time. This lack of competence which is internalized influences its realization within the class. Therefore, it seems that in order to establish "pedagogical competence", most teachers rely on individual strategies that are not very sustainable. It is in this sense that these lines of thought deserve further exploration in the light of the theoretical model of Trinquier (2011) on representations, among the consensual elements, that attitude constitute the central core of representation as an “evaluative element”. It participates in sociological anchoring via the process of "meaning assignment". Operator of contextualization, the representation of the cuff’s teaching on physical education teachers refers to teaching conditions perceived as facilitating, restrictive, or without effect on the action.

Thus, the conditions evoked by these can be of the following types: macrosocial (it means that society allows teachers to exercise their profession); mesosocial (type of student population in relation to the geographic location of the school in which they practice); microsocial relating to the classroom situation (classroom climate, student reactions). All of this underlines the need to test the relationship between the situations of cuff’s teaching in Congolese physical education teachers and their practices, through their experiences, the typologies of practices and the didactic positioning. The purpose of this study is to identify and analyze the representations that physical education teachers make and their effects in the teaching / learning process of the cuff. To study this problem, we started from a main question formulated as follows: Do the representations of physical education teachers influence the teaching / learning process of the volleyball cuff? From this main question arise the following secondary questions: What are teachers' representations of the teaching of volleyball cuff in middle schools and how are they structured? To answer these questions, we hypothesized that: teachers' representations of the volleyball cuff depend on the motivational, socio-professional and pedagogical factors which are associated with the assigned tasks. To do this, questionaires intended for physical education teachers and interviews were conducted with other teachers in order to provide information on, the kind of the evoked representations and the relationships between the representations and the declared practices.

Research model

The mode of investigation was based on a mixed approach (for example, qualitative and quantitative), on the basis of a cross-sectional survey. To assess teachers’ representations structure of cuff’s volleyball, questionnaire and interwiew were used. For Abric (1997), this instrument is one of the most used in the sciences of education, because it does not require any limitation on "the expression of the respondent to the strict questions that are proposed to him", particularly through the use of items or questions evocation. According to the author, the recent development of data analysis methods applied to education reinforces the privileged position of the questionnaire. With regard to interviews, these are techniques very often used to collect opinions, beliefs, ideas and attitudes concerning various social objects (Molinier et al., 2007). The adoption on an approach of triangulation of qualitative and quantitative methods which is applied to our study, relates to works linked to representations of teachers (Moldoveanu et al., 2016). The study was conducted between July 6 and 30, 2018 in Brazzaville (capital of the Republic of Congo). The population of this city is estimated at 1,838,348 inhabitants, of which 573,416 (31.2%) are pupils of the secondary education (CNSEE, 2021). Interestingly, we want explore the representational domain through professional practices and their relationship to knowledge. Therefore, this research is part of a comprehensive policy for physical education teaching in Congo, taking into account the physical and social environment conducive to activities, collective activity programs and physical and sporting activities.

Sampling and respondents

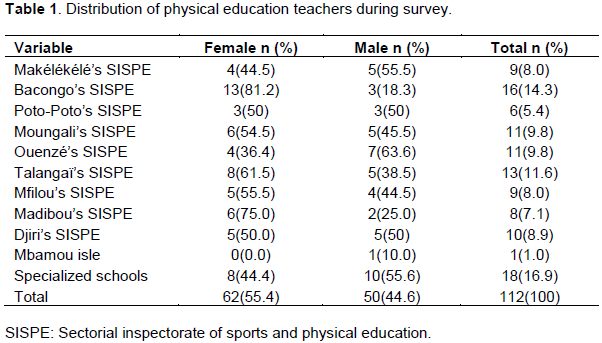

The population of this study was 112 physical education teachers working in public middle schools administered by the nine (9) sectoral inspections of sports and physical education (SISPE) and specialized directorates of the city of Brazzaville (Table 1). The inclusion criteria for subjects were: written consent to participate in the study; seniority in the physical education teaching at least 3 years; experience in physical education teaching in the third year; exercise of the of physical education teaching in a middle school during the period of study. At the end of the sampling operations, 94 teachers were selected and took part in the study. These were 54 women (57.4%) and 40 men (42.6%). They worked in 18 general education middle schools and 3 technical education middle schools in Brazzaville.

Experimental protocol and design

The questionnaire, by its standardization, was chosen in order to reduce both the subjective risks of data collection (standardized behavior of the interviewer) and the inter-individual variations in the expression of subjects (standardization of the expression of respondents: same questions for all subjects, same award conditions, do not always require the intervention of survey manager). It was chosen for its ease of use and its standardized nature. The questionnaire, consisting of 9 questions, aimed to collect factual information on the attitudes of teachers on volleyball cuff’s teaching. It was structured in: closed questions, open questions, multiple choice questions. These made it possible to obtain precise answers (closed questions), to collect personal evocations (open questions), and to compare the opinions of the teachers with the proposed answers (multiple choice questions).

The questionnaire was structured in three parts. Part I, which contained 5 questions, focused on the identification of teachers (grade, gender, seniority in the exercise of physical education teaching, establishment, inspection and classes held). Part II consisted of 4 questions focused on sports preferences, volleyball programming in establishments, training, facilities and teaching materials. Part III concerned the teachers' comments on the didactic aspects of cuff’s teaching in middle schools (pedagogical approach to receiving ball, observed difficulties, remediation of shortcomings while learning the cuff gesture). The questionnaire was distributed during the examination of Diploma of the Brevet d´Etudes du Premier Cycle (equivalent to General Certificate of Education Ordinary level, GCE"O" level), July 2018 session. Finally, 86 questionnaires duly completed were collected.

The structured and intensive interviews made it possible to collect information concerning the opinions of teachers in their relation to knowledge of volleyball cuff (or professional knowledge). Duration of each interview took place between 45 min and 1 h. A total of 18 interviews were conducted using an Enet®M50 Digital Voice Recorder branded didactophone, China (Recording time: 15,160 min; frequency: 16 KHz). These directive and intensive interviews were carried out without video support, because we wanted to collect the familiar actions spontaneously recalled in memory. Examples of questions asked: How do you feel about teaching the volleyball cuff? Is it difficult or not? Why? Have you realized it already? Do you think you will achieve it? The analysis of these 18 interviews aimed to identify among the representations evoked by the teachers about their behavior and their attitudes (representations describing the practices and justifying them) those having a generic character, that is inter-individual manner with a majority of teachers.

Regarding the analysis of the scope and structure of the representation of the headline among teachers, firstly, PE teachers were asked to write down the first ten words that spontaneously came to them, and mind when they heard the word "headline". The function of this free association phase was to activate the field of representation, that is to say the elements of the content connected directly to the word stimulus. Secondly, each teacher had to deepen their memory research by giving five nouns, five verbs and five adjectives, the order of presentation of the request being randomized. In other words, it was to allow the teacher express, by nouns, the referents associated with the word "headline"; by verbs, behaviors related to the inducer; and by adjectives, value judgments. The search for stabilizing elements of attitudes observed among teachers, a Likert scale made it possible to measure the affective dimension of attitude using a semantic differentiator inspired by that of Osgood (Trinquier, 2011). It made it possible to characterize the attitude based on the characteristics given to the cuff, its degrees of power as well as the value judgment inspired by the mastery and execution of this technical gesture. Osgood's semantic differentiator uses the principle of verbal associative bonds mediated by a semantic impression, that is, a process of signification by which a verbal stimulus (a word in our study 1 represents a signified) is associated with a verbal response (another word with a positive or negative connotation). The connotation attributed to this second word reflects the emotional position (polarized or not) of the teacher vis-à-vis the teaching of the headline; the evaluative dimension, which is attached to social representation (Moliner et al., 2007), participates in anchoring via the process of "meaning assignment".

Data analysis

The content analysis of the data collected was carried out in three stages: transcription of all recorded interviews; condensation of the transcribed data; qualitative analysis of the content of collected data. For this, the interviews with the teachers were treated qualitatively from a thematic analysis. Thus, we took into consideration the analysis of each speech proposed to account for the personal and institutional relationship to teachers' knowledge. Primary data analysis and initial analysis of the data collected, helped make sense of the data collected to answer research questions and test the hypothesis that a study is initially supposed to assess. It should be noted here that in our text, first names were included in the interview report. These are included for illustrative purposes only, in no way revealing the identities of the surveys. Descriptive (univariate) and inferential (bivariate and multivariate) statistics were used to analyze the data obtained. Results are presented as numbers and percentages for qualitative data. The level of internal consistency of the questions has been checked. It was estimated from Cronbach's α index, which is considered acceptable for values ranging from 0.62 to 0.87 (Crocker and Algina, 1986): its value was 0.84 to 95% for a confidence interval (CI) of 0.83-0.88. In this study, chi-square (χ2) test was used as a test of association; it was applied to determine the association between the included variables. This is a test to determine whether or not there are relationships between the perception of the achievement of the cuff and the adoption of an appropriate attitude, as well as between the determinants of the implementation of an appropriate teaching program in the cuff. In other words, chi-square test was used to determine whether there is an association between the variables includeed in the theoretical model. Finally, multinomial logistic regression was used to find out how the level of initial training, duration in the exercise of physical education teaching, and some pedagogical variables could influence the implementation of cuff’s teaching. p≤0.05 defined statistical significance. All statistical anzalyses were performed with SPSS for Windows version 25.0, at the Laboratory of Statistics and Numerical Analysis of Faculty of Sciences and Technology, Marien Ngouabi University

Questionnaire data

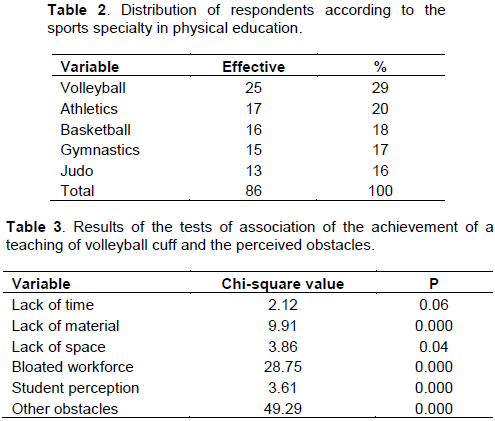

Analysis of the data collected reports that volleyball was scheduled in 24.7% of cases. The reasons for non-programming in schools were: lack of teaching material (net, ball, etc.), space and overcrowding. The distribution of respondents according to the sports specialty chosen during the last year of academic season at the Higher Teaching of Physical Education Institute is shown in Table 2.

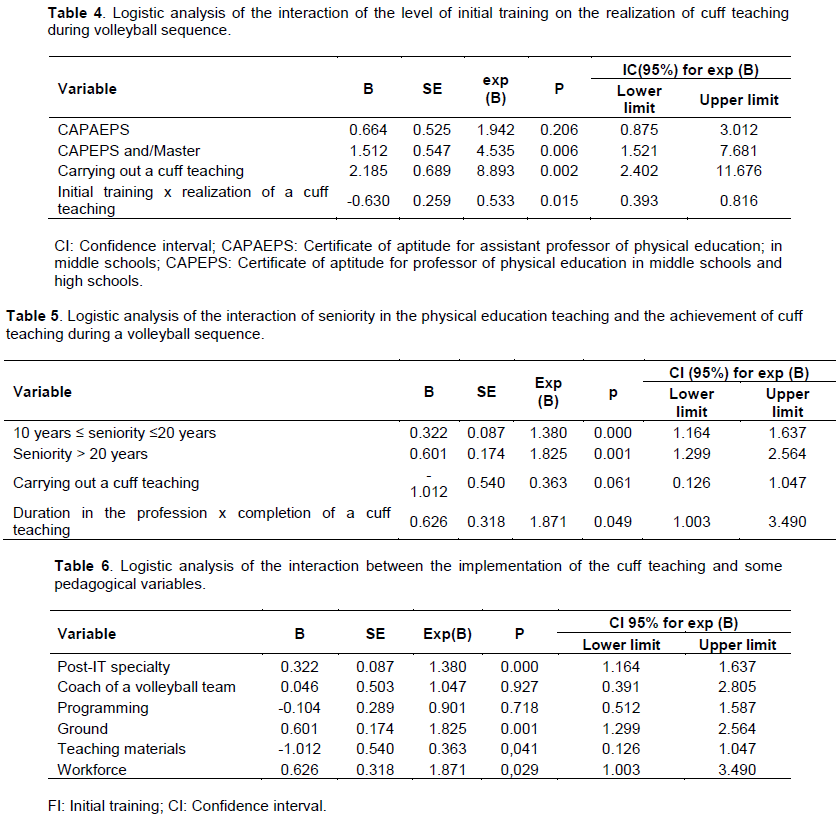

The data in Table 3 show that, according to the teachers' comments, the main obstacles to volleyball cuff’s teaching are the excessive effectives of classes, the lack of apparatus and other materials of volleyball practice, the lack of space, and the perceptions of the pupils. Among the other obstacles, the difficulty of the pupils to reach the return the ball following the effects of ball during the realization of the headline was cited. Moreover, the logistic analysis of the interaction of initial training’s level on the achievement of cuff teaching during a volleyball sequence (Table 4) reveals that there is a significant difference between the of initial training levels (CAPAEPS versus CAPEPS and / or Master EPS) and the realization of cuff teaching.

The other results of the logistic analysis is concerned with the interaction between, on the one hand, seniority in the exercise of physical education teaching and the achievement of a cuff’s teaching during a volleyball sequence (Table 5) and on the other hand, the implementation of the volleyball teaching and some educational variables (Table 6). It emerges from these data tables that: the duration in the exercise of physical education teaching is a determining factor in the achievement of cuff teaching; cuff’s teaching is dependent on the teacher's post-IT specialty, field, teaching materials, and class size.

Corpus of teachers' entretienings

The most significant representation put forward by 7 female teachers questioned out of 9 of the same sex working in middle school concerns the difference in sex with respect to their pupils, which is systematically taken into consideration in the management of the class. This presupposes, on the part of teachers, gendered representations of pupils as well as interpretations of social behavior and interactions based on a gendered reading grid. For example, for Rose, a PE teacher for 7 years in a technical middle school with little mixed streams, some made up mostly of boys, others mostly of girls, it would be heterosexual seduction that influences the relationship with pupils:

"I think in my middle school, it’s easier to be a woman, because for my male colleagues, it’s more difficult to perform the volleyball cuff. The girls are really, in quotes, in seduction ".

Sex is not necessarily perceived as a disadvantage for the teacher to teach this gesture, although it is here "the girls" who are perceived as "the problem". At the same time, the same teachers spoke of the difficulties experienced in winning at the start of the scholar year in front of classes made up exclusively of boys:

"For my first job, I was in an almost 100% male establishment. […]. First job, I was a little lost and ... I had a class recomposed between secretary, accountancy, electricity, masonry and mechanics, restoration and mechanics: explosive! And ... this is a class that I had a hard time asserting myself with. Besides, I didn't have a lot of years behind them".

If previously, Rose insisted on the ("easier") advantage of being a woman in her school, in this excerpt she evokes her difficulty in establishing herself among a group of pupils qualified as "100% male" from several specific fields, and with whom she considers that she has little difference in age.

Sandra, another physical education teacher in an industrial technical middle school, also underlined a difficulty in asserting herself with a class mainly composed of boys:

"it is very difficult for me to adapt to such turbulent students and, moreover, only boys, since we only have boys in middle school […]. I have not yet found the solution to succeed in channeling them ".

As Rose, pupils’ deviant behaviors are perceived to be exacerbated because of their gender. She extends this interpretation of the link between sex and its difficulty, by postulating that the latter is shared by the pupils. She expresses herself by putting herself in their shoes:

"Wow! Is she the teacher? Have you seen the teacher?

It's her!" And there, I said to myself: “Wow! It's going to be hard!" Because they're like, “Oh yeah! She's a young woman, she's a woman; we are just guys, it's going to be good for her! It'll be nice!" [Ironic attitude]".

Sandra will eventually succeed in establishing herself in class and teaching the cuff despite initial apprehensions related to these reports and representations:

"Even though I'm a woman, it's going very well [...] it isn’t of disadvantage, in quotes, to be a woman in front of a male audience."

The testimony of Aurélie, physical education teacher in a middle school, also explains the level of difficulty or ease in imposing authority through social relations of sex, although her interpretation of this link differs from that of Sandra:

"There were mixed classes with whom it was going well. On the other hand, the classes of boys, it was very difficult to manage […] for a woman".

Aurélie then pays attention to her professional outfits and to her language register with the pupils in order to recall her institutional status as a teacher who legitimizes her authority:

"I have always dressed ... [...] never a dress and never a skirt in the establishment. Never a cleavage. […] Especially in relation to boys. I called myself: "madam" instead of "mademoiselle" also, that already poses […] a distance ".

Nevertheless, Aurélie also points out difficulties with pupils of the same sex. She talks about it in these terms:

"There is the difference in sex. I think a boy ... well we both had problems: him, as a man, he had conflicts with boys. I, as a woman, had conflicts with, in fact, the girls".

Finally for Isabelle, a physical education teacher with 5 years seniority in the profession, it would rather be the origins that overlap with sex relations to make it more or less difficult to impose their authority in the implementation of teaching / learning this gesture:

"And then, it's a mixture of cultures and origins too, that means that not everyone has the same view of things. There are still pupils from other African countries, who for them ... women are nothing, in quotes, and therefore, who have difficulty understanding authority. Suddenly, there were, all the same, a lot of clashes. What made me relate was that it was not just with me, but with other colleagues as well, young female teachers, with whom it was difficult. […] So, the classes are quite difficult, in general, but there is one which is particularly unlivable and very difficult, which is resistant to authority in general, but even more so to female authority. And, I'm not the only one, eh! Several colleagues from the teaching team with this class have had a lot of problems at the start of their profession, just to show authority ".

Thus, for this almost beginner teacher, the difficulties in imposing her authority over an audience of male pupils are perceived as being linked to a combination of factors, gender and "cultures" or "origins".

The questionnaire data show that the cuff teaching during a volleyball sequence was achieved by only 18.6% of teachers who opted for volleyball as a specialty in team sports in initial training; the main motivational factors for not performing this activity were an unpleasant gesture, a restrictive technique, fear of failure, lack of mastery of gestures, problems with contact with the ball, complexity of gestures, and poor achievements in initial training. These results confirm our hypothesis which states that: teachers' representations of the volleyball cuff: teaching depends on the motivational, socio-professional and pedagogical factors which were associated with assigned tasks. Our observations show that the teaching of volleyball is not regularly provided in accordance with the official texts, particularly decree n° 84/581 of June 20, 1984, making compulsory the organization and the practice of physical education in all sequences of physical education in the Republic of Congo. Volleyball was to be taught in middle school in 6th and 3rd year classes (INRAP, 2005). Indeed, the development of the annual programming of PAS in schools is developed either by the coordinator (head of department) or by Educational Research Groups (ERG-PE) depending on the school. The ERG within an educational establishment is called upon initially, to observe the institutional prescriptions (respect of program book) by developing pedagogical strategies, which take into account the activities selected by the State on the one hand and by putting in place of procedures and knowledge, used in didactic research to build skills. This approach goes hand in hand with the official instructions (OI) of the Republic of Congo which stipulate that the annual programming must be established at the behest of the coordinator and by all teachers who are jointly responsible. Without under-estimating the difficulties encountered in the collective development of such a document, it is necessary to establish it on the basis of the official program, program of sports events, state examinations and material conditions (sports facilities, small equipment, etc.) (OI,1970). Therefore, the programs should have a strong professionalizing dimension with training content focused on the process of transmission-appropriation of practical knowledge (Romar and Ferry, 2019). Following this, Gil-Arias et al. (2021) suggested that physical education programs must demonstrate the presence of didactic skills, and promote the products trained to design and animate teaching situations. In reality, the programming of the PAS observed in the pedagogical documents of the respondents in the various establishments, was based on the availability of equipment. The link between quality of infrastructure and teaching of programmed PAS was found (Table 3), because schools did not have the necessary infrastructure and equipment appropriate to volleyball teaching, especially cuff training.

Results of the present study support the hypothesis that teacher’s representations of volleyball cuff’s teaching depend on the motivational, socioprofessional and pedagogical variables which were teacher’s with assigned tasks. Regarding the motivational factors found, pleasure was one of them. In this regard, Haye (2012) thinks rather that in physical education, "pleasure is not a problem, only its absence is a problem" (Haye, op. cit.: 15-16). The words of this author show that the feeling of pleasure, which explains part of the motivation, is the effective way to give meaning to teaching. The displeasure of cuff teaching being found in 91.42% of the teachers, our observations consolidate the remarks of Haye (op.cit.), and those of Quennerstedt (2019) which testify to an essentially technicist conception of volleyball teaching, namely "Teaching volleyball consists primarily of teaching subjects to perform basic technical gestures (pass, cuff, attack and serve, etc.)". Indeed, the basis of volleyball teaching is focused on learning the fundamentals (technical gestures). This is why the teacher has the obligation to mobilize, maintain the interest and motivation of the pupil in the field of task. Without losing sight of the goal to be achieved, the teacher makes it more pleasant to achieve with his help. It is in this perspective that Eloi (2000: 3) thinks that it is the quality of the representations (those that the subject has of the environment in which he makes but also those that the subject has of the environment in which he makes but also those of the action), which makes it possible or not to achieve the set goal.

Another obstacle for teachers is pupil’s behavior. This is the behavior of the pupils, level of volleyball practice deemed insufficient, lack of time to keep pace with the learners, feeling of not knowing how to do otherwise and management of pupil’s behavior which is not facilitated during the cuff teaching. This fact is also found by Scrabis-Fletcher and Silverman (2017), Magendie and Bouthier (2013) among secondary school students. Thus, when we confront the observations with the reference theory of Trinquier, which argues that "the analysis of a representation, the understanding of its functioning necessarily requires a double identification: its content and its structure" (Trinquier, 2001:72). Thus, it is possible to suggest that the time devoted to cuff teaching is insufficient to promote the acquisition of fundamental gestures. Given the high effectives noted in the majority of classes in Congolese middle schools, one assumes that the practice time allotted to each learner is insufficient to ensure the acquisitions. This low rate of practice time available to learners is explained by the nature of activities retained by teachers during the volleyball sequences which are, centered on gymnastics and athletics, as Mviri points out (2018). During the observation of 42 physical education lessons, the author notes only 16 included sequences focused on volleyball and only 4 were assigned as cuff learning. However, the interpretation of reasons linked to valuation and devaluation mentioned by the teachers is difficult because this appreciation is subjective. In fact, we do not have access to the feelings of these, moreover, one with regard to the valuations; it would take an implication of pupils to find out whether it is automatic or thoughtful encouragement, the former not being credible on teachers. When we compare what is observed as the teachers’ reasons for their actions, we note a Pygmalion effect (Al-Tawel and Al-Ja’afreh, 2017; Rosenthal and Jacobson, 1969). Physical education teachers who have low expectations of learners tend not to put in place pedagogical practices to deliver a course on their schools’ cuff volleyball (Silva et al., 2020), thus reducing the chances of learning and learning. Finally, our physical education teachers have their own ability to teach this gesture.

Our results also showed that the physical education teachers who chose volleyball as an option during initial training constituted 18.6% of the total teachers who taught the cuff gesture (Table 2), notwithstanding their inclusion in the timetables, at the rate of two hours per session and twice a week. This suggests the intervention of teachers specializing in volleyball in schools in order to relieve non-specialists of this teaching, an approach which is not possible. However, we understand why the majority of these teachers were in favor of removing volleyball from the middle school curriculum due to poor learning. By the way, in Europe during PAS courses, pre-professionalization already confronts the supervisor with real situations coming into questioning more theoretical aspects of training (Backman and Barker, 2020; Milos et al., 2019). The transition to the status of trainee teacher from the first year of training in physical education teaching induces a complexity of process; by highlighting a system of standards, it upsets certain conceptions of teaching and leads the trainees to build new knowledge, plural and combined in action (Sood Al-Oun and Shaddad Qutaishat, 2015), absence of practice of some PSAs by physical education teachers is a sad reality in Congo. However, according to Gil-Arias et al. (2021) it is by practicing PSAs that we build knowledge. Indeed, the training transmits often representations which can be in competition with the initial representations; it follows difficulties in terms of the acquisition of knowledge. While it is therefore undeniable that they are of capital importance, we cannot however hide some other parameters which will influence and participate in the own development of learning (Therriault et al., 2011).

Therefore, the concept of competence, often discussed, needs to be clarified. In our study, it takes place with the level of initial training (Table 4) and seniority in the teaching profession (Table 4). From a general point of view, De Ketele (1985) emphasizes its inclusive and finalized dimension. Competence, by updating in a complex practice and by mobilizing prior knowledge and know-how, transforms them and develops attitudes and skills to become, oriented towards the purposes of teaching. Perrenoud (1995) refines this definition by specifying that competence mobilizes heterogeneous cognitive resources: patterns of perception, thought and action, intuitions, values, representations, knowledge, etc. This set is combined in a problem-solving strategy at the cost of reasoning made up of inferences, anticipations, evaluation of possibilities and their probability of success. More specifically, during the teaching-learning process, the professional skills of teachers cover plural knowledge used in the planning, organization, and cognitive preparation of the session and in the practical experience resulting from interactions in the classroom. This knowledge is crossed by a strongly affective dimension (Ferry, 2018). Indeed, outside the presence of pupils, the teacher is led to question his own relationship to knowledge; within the framework of interactions in class, he must also manage the reactions of the group, anticipate possible drifts and distance himself from his own emotions when the situation particularly affects him. Finally, knowledge integrates a social dimension because, during the training process, exchanges with different actors (trainees, trainers, etc.) participate in professional construction. It is at this level that other types of knowledge (about and for action) are to be built for oneself and with others.

Thus, the achievement of the cuff teaching by teachers is dependent on the expectation of competence. It has been indicated for this purpose that in terms of self-knowledge, the feeling of competence or personal efficiency, “I can teach the gesture because I feel competent to carry it out” is an important component (Bandura, 1990). These elements reinforce the idea that the choice in teaching technical skills for our teachers is made on the basis of knowledge of their "representation of competence". However, according to Connell et al. (1994), competent feeling in an activity would not be a determining factor in choosing a PSA. These comments reinforce those of Délignières and Garsault (1991): "the fact that a subject feels competent in an activity will certainly encourage him to continue it". The feeling of competence is thus considered as an important component among the determining factors in a choice education. Another reason of score sequences centered on cuff volleyball is lack of time; it is the main reason to promote the acquisition of this gesture. The participants also indicate among other obstacles the feeling of not meeting the expectations of the scholar institution. Indeed, it appears that the institution requires bringing learners to a practice level 2 according to the codification of the French Federation of Volleyball for beginners, without being able to provide the hours necessary to achieve this. Consequently, the teachers do not take the time to set up learning tasks that would be more favorable to the acquisition of gesture by the learners, nor to produce feedback that would further develop the skills, but prefer to go quickly to complete the programs. The result is that learners are not exposed to sufficient amount of input and do not perform activities that would allow the in-depth processing of this input which further hinders acquisition. In addition, management time becomes more complicated when it is crossed with the management of pupil behavior. Discipline is a central element in the discourse of the teachers observed and seems to partly explain their choices. We can therefore see the importance of taking a step back from the representations that we construct about teachers in the face of their involvement in order to be able to set up practices consistent with the Trinquier’s theory. With regard to the other difficulties encountered by the pupils, the return of the ball was cited by the teachers. This obstacle is also underlined by Osborne et al. (2016). According to these authors, students often hit the ball on the left or right parts of the landing plate because of its poor formation (presentation of the outer sides of the forearms instead of the inner parts). This learning is fundamental and constitutes a major achievement for the practice of volleyball at a high level (Degrenne, 2019; Langlois, 2018) and takes a lot of time (2 to 3 lessons depending on the size of the class). To remedy this, it would then be advisable to increase the number of groups within the class and also the number of balloons. In the context of poor sports equipment in schools in the Congo, only a significant contribution from the state can substantially improve the conditions for learning this volleyball cuff gesture.

Finally, from the analysis of corpus of our interviews, it emerges that the representations on the cuff volleyball among the physical education teacher impact pedagogical relations and reinforce the construction of differences between the sexes. Indeed, as Guichard-Claudic and Kergoat (2007: 3) note, "it is on the body that we base the idea of skills specific to each sex". In addition, since authority is perceived according to some representations as a male competence, it is associated with bodily characteristics also represented as male, an observation which remains consistent with those resulting from other studies (Ananga, 2021; Nuria et al., 2018). The gendered body thus appears, through our results, as a social element to be carefully staged (Butler, 2005; Verscheure et al., 2006). In short, the results of the representations of our teachers suggest that social relations of sex are perceived as having to be thwarted, overcome or deconstructed in order to found “professional competence” (Prairat, 2012). This is a set of pedagogical strategies deployed by physical education teachers to "manage impressions" (Goffman, 1996) and their own representations of the skills involved in cuff teaching. These strategies involve establishing institutional order by negotiating the success of this power, or "statutory authority" endowed by the educational institution (Mayeko and Brière-Guenoun, 2019). In addition to strategies for neutralizing the gendered body, some teachers in our study accentuate the skills gap in age in order to consolidate their non-dominant position, by playing on this other system of unequal social relations (Bessin and Blidon, 2011). Others prefer attitudes or behaviors that compensate for gendered representations. They express that they are not "afraid" of the mistrust placed on them as regards to the supposed physical strength of their male counterparts by "asserting themselves immediately" in order to prevent gendered representations from continuing. All of these strategies aim to bring together the conditions allowing them to move towards educational authority by taking into account their representations towards the volleyball, particularly the cuff technique.

However, certain precautions should be taken into account when interpreting the results presented. The type of questionnaire constructed to identify teachers' representations was based on a hybrid questionnaire. If according to Abric (1997), this tool has the advantage of borrowing other methods in the context of work on social representations, Nachmias and Nachmias (1996) (1996) maintains that the open questions used present a certain number of drawbacks, linked in particular to the fact that the information collected may be too dispersed. In addition, the use of open-ended questions teaches that many answers can be fuzzy, incodable. However, the free association method advocated by Abric constitutes a compromise about the choice of open / closed questions, through the "open-ended" questions that we used in this survey. In addition, a second weakness of the study is the small number of subjects (n = 86); this does not authorize the generalization of the conclusions obtained to the entire population of physical education teachers in the Congo. The third limitation is that participation in the study was strictly voluntary. Again, there is a good chance that the teachers must be motivated by their practice participated, to the detriment of the less enthusiastic teachers, and therefore the most likely not to teach the headline during the volleyball lessons. These limitations do not, however, completely affect the power of the observations. However, this study has the merit of having addressed the evaluation of the representations of physical education teachers in black Africa regarding the teaching of volleyball cuff. In addition, our experimental work followed protocols similar to other previous studies on representations (Al-Tawel and Al-Ja’afreh, 2017; Castejon and Giménez, 2015).

The study concludes that in volleyball cuff’s teaching during physical education lessons, teachers’ knowledge of representations is essential. Our results highlight seven main reasons and obstacles for teachers: lack of time, lack of material, lack of space, excessive numbers, perception of pupils, seniority in the teaching profession, and level of initial training. Even if some teachers have a significant personal connection to the knowledge to be taught, the majority of them present themselves as teachers working in a relatively difficult ecological and educational context. Their representations highlight pedagogical misunderstandings, that is to say differences in representation. They participate in socio-professional, motivational, ecological and didactic variables, by acting on practices. By reinforcing, neutralizing, colliding, or not meeting, they hinder or on the contrary help the process of teaching this technical gesture.