ABSTRACT

The aim of this study is to indicate the problems that Syrian refugee children, class teachers and Turkish children face in their school environment. The data of this study were realized via case study design which is one of the qualitative investigative designs. Interviews were carried out using the observation notes of the prospective teachers as well as their semi-structured discussion forms. As a result of the content analysis of data obtained from the research, it was seen that the most significant problem faced by the study participants was “language problem”. In connection with the language problem, it was seen that factors such as adaptation, communication, and pedagogic condition, social and emotional development influenced them negatively. As the Syrian students do not know Turkish and they are taught with the traditional methods, they do not benefit from the teaching activities and they get bored in classes. While this situation causes behavioral problems in the classroom, the teachers spend more time with the Syrian students. This makes them to fall behind and not to finish the curriculum in time. It is recommended classroom teachers should receive training on how to teach in a multicultural classroom, language courses should be opened, designated based on their age and knowledge of Turkish to solve the language problem of Syrian children and adults and classroom teachers should receive "Teaching Turkish as a Foreign Language" education.

Key words: Syrian refugee children, integration, class management, multiculturalism, immigration.

Turkey has always been a country receiving immigrants or a transit country due to its location. After the “Syrian Crisis”, which started in March 2011, Turkey began receiving immigrants from its neighbor Syria. Turkey has become a country where most Syrians immigrated as a result of the “open gate policy”. According to the data from General Directorate of the Immigration Office (URL, 2020a) dated February 2020, the number of refugees coming to Turkey has reached 3.587.566. According to the February 2020 data of the Refugees Association

(URL, 2020b), approximately 520,000 of this number consist of children of elementary school age.

The Syrians were given shelter and medical facilities considering the fact that immigration would soon come to an end and they would return to their country. Most people thought the war would last longer than it was expected; hence activities in the field of education were also dealt with. It is obvious that extreme increase in the number of refugees and dispersion of most of the refugees out of the camps have led to challenging problems in education, as well as in other areas. Besides being involved in designing education in the camps, from 2013 on Turkey has taken crucial decisions and implemented them to design education outside the camps (Seydi, 2014).

By the end of 2019, education for the refugee Syrian children had been carried out within and outside the camps via Temporary Education Centers and State Schools and private schools owned by Syrians. The Syrian children who attend state schools receive education from Turkish teachers in accordance with the Turkish curriculum in the same classes as the Turkish children. As for the Temporary Education Centers (TEC), there are education centers which offer education in Arabic to the Syrian children and youngsters at the school age according to the Syrian curriculum covering the elementary and junior high levels. The curriculum implemented in these centers is the Syrian curriculum and it is carried out by voluntary Syrian teachers. These teachers are paid via a project within the scope of UNICEF and PTT (Turkish Postal Service) collaboration (Emin, 2016). Following the end of 2019, GEMs were closed and the strategy of giving education to Syrian children only in state schools was adopted (URL, 2016a).

The abundance of actors for the education of Syrian refugees – such as the host country, UN, NGO’s (Civil Social Groups), disparity of the expectations and power conflict complicate the refugee education (Özer et al., 2016). In the countries where Syrians have migrated, due to the political decisions in education and the gaps in the implementation, the lack of legal status and the role of the international actors, several difficulties have aroused in the realization of these decisions (Buckner et al., 2018: 444). In spite of all these difficulties, Turkey has contributed extensively to the Syrians under her reassurance by pursuing “open gate policy”. A lot of practices have been done and are still in progress such as the schools in the camps, education in the state schools with the Turkish children under the same conditions (DillioÄŸlu, 2015: 10), education given in GEMs in their own language and curriculum for them not to lose a school year when they return to their country, in-service training to the Syrian and Turkish teachers, training to the contracted teachers to teach the Syrian students in Turkish, training to the counselor teachers for support for the Syrians, training to the teachers who have alien students in their classes (URL, 2016b). In spite of all these practices, there are still educational problems for the students. Tüzün (2017: 12) outlines some of the problems as follows: physical capacity of the schools and classrooms, potentiality for psychosocial and academic support, facilities for language learning, discriminatory attitudes, isolation and peer violence. It is seen that, in the construction of a common future, completing the regulations for the Syrian children to be involved in the education system is not sufficient although it is a crucial step for the resolution of the problems. Structural obstacles in spite of convenient regulations, frequently seen poor living conditions of the refugee children, poverty, need to work, insufficient care, in case of ambiguity inconsistency of the families for education and changing assessments for the good of education all influence access to education for the children (Özer et al., 2016: 194) and the level of benefiting from education. A similar situation is experienced by Syrian children who emigrate to Lebanon. Due to the burden of educational expenses or to help their families economically, fewer children attend school; but more children attended school when their families were supported economically on the condition that their children must continue studying (De Hoop et al., 2019).

The school and the teacher have an important point in the life of a child. In addition to all the deprivations in their lives, being in another country as a refugee in the same environment with people whose language they are not familiar with is much more difficult for those children. Adjustment for the Syrian students to their classes and freeing themselves from unfavorable experiences are closely related to their teachers’ approach and attitudes. In this sense, the teachers working in elementary schools have a great responsibility. Adopting themselves to the normal life after such misfortunes and loving the country they are living in are compatible with the attitudes of their class teachers (SaÄŸlam and Ä°lksenKanbur, 2017: 312; Rubinstein-Avila, 2017).

In the literature, there are many studies about the problems Syrian children experience in their countries of migration. A study examining the inclusion of Syrian refugee children in school systems in Sweden, Germany, Greece, Lebanon and Turkey shows that these children are not given a high-quality education and rich materials and teachers are not trained to learn a second language (Crul et al., 2019). At the same time, Syrian children have been struggling for years with war and they have to emigrate from their countries. They witnessed the torture, maiming and death of their neighbours, brothers and parents. In the places where they emigrated to, they were subjected to discrimination and racist behaviour without receiving proper education, shelter and food. Therefore, many of them experienced depression and anxiety (Kandemir et al., 2018). A study that compares school systems in Europe with respect to refugees found that perceived discrimination is a strong negative predictor of a person's separation from school and the society in

general. Due to the compulsory education age limit, when students who start school late due to immigration finish primary school, the alternatives for multi-choice secondary schools are either vocational schools or low-level schools. This poses problems for children who are unable to realize their complete potential. In European countries, Sweden is a good example. After determining literacy and math skills of children from the country, they were placed in a training program to fit their needs (Koehler and Schneider, 2019; Chimienti et al., 2019). In a study of Syrian refugee children and their families who settled in Canada, Syrian children did not only have difficulties in making friends among local students, but were also subjected to constant bullying and racism which in turn affects their sense of belonging and connection. To prevent this, it is suggested that the children of the host country be informed about the difficulties experienced by Syrian children (Guo et al., 2019). In a similar study conducted in Turkey, it was shown that class teachers had difficulties in teaching Syrian students reading and writing in Turkish as a foreign language and also it appeared that they experienced many problems developing their language and communication skills (Işıkdoğan-Uğurlu and Kayhan, 2018). This and many similar studies examine the academic and emotional problems experienced by Syrian students.

This study investigates the problems experienced by Syrian children, children of the host country and classroom teachers. The difference and importance of this work is created by the point that the events experienced by classes with Syrian children were analyzed from a multifaceted point of view arising both from Turkish and Syrian students and from the eyes of the trainee teachers. Syrian students experience a lot of problems as well as the class teachers and the other students in the same class. As it is necessary to know how the laws, regulations and legislations were introduced in 2011, how the practices of NGOs and how the UN, integration and inclusive educational activities are taught to the Turkish and Syrian students and class teachers in the school environment, the main objective of this study is to discover the problems that Syrian refugee children, class teachers and the Turkish children face in the school environment. For this purpose, responses to the following questions were sought:

1) Which problems do the class teachers who have Syrian students in their classes face?

2) Which problems do the Syrian students who attend state schools come across in class?

3) Which problems do the Turkish students who have Syrian students in their class face?

4) What are the solutions of prospective teachers to the problems experienced in a multi-cultural class?

Pattern of the research

This research has been designed as a qualitative case study in order to designate the problems which class teachers who have Syrian students in their classes, Syrian students and Turkish students. Cases appear in several forms such as the events that we come across in daily life, experiences, perceptions, tendencies, concepts and circumstances. Case study is used for studies that aim to investigate events which are not completely unfamiliar to us and at the same time the meaning of which we do no grasp appropriately (Yıldırım and Şimşek, 2016: 69). The difficulty of conducting experimental and semi-experimental work on displacement and other humanitarian crisis environments is well known (Puri et al., 2017). It is observed that the trainee teachers started their internship in order not to disturb the Syrian students and not to disrupt the classroom environment.

Study group

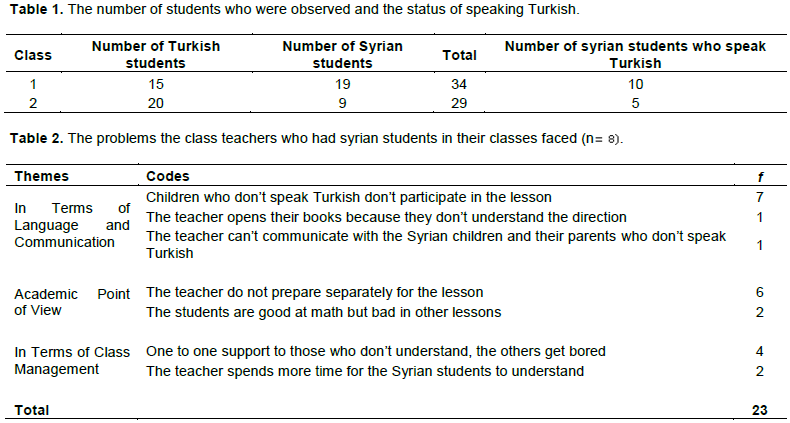

This study was carried out in the 2018-2019 fall semester with 8 senior students of the class teaching department who went to practice teaching in schools where there were Syrian students. When the study group was chosen, typical situational modelling –one of the relevant modelling methods – was used. In accordance with this study, “students who went to schools for observation where Turkish and Syrian children studied together” were chosen. Typical situational modelling is to designate the typical ones out of several situations in the universe (Büyüköztürk et al., 2018: 93-94). 4 of the eight prospective teachers had observations in the first grade, the other 4 in the second grade. The characteristics of the classes where observations were held:

First Grade: The total of the students is 34, 15 Turkish and 19 Syrian.10 of the Syrian students speak Turkish, 9 do not. In the classroom, there are a computer and a projector, a locker for the teacher and a cabinet for the students to put their lesson material in. They arrange posters depending on certain days and weeks, but visual aids related to lessons are made up of works done by the prospective teachers.

Second Grade: The total is 29, 9 of which is Syrian. 5 of the Syrian students speak Turkish. The classroom layout is the same as the first grade.

In Table 1, there are 34 students in the first class, and more than half of them are Syrian students. Of the 19 Syrian students, 10 are fluent in Turkish. Among the 29 students in the second grade, 9 are Syrian. 5 of these children can speak Turkish.

Collection of data

The data of this research were gathered via observations from the interviews with the prospective teachers who went to schools for observation where Turkish and Syrian children received education As a result of literature scanning, open-ended 12 observation questions were prepared in order to determine the problems the teachers, Syrian and Turkish students had in the class environment. The observation questions were arranged and developed after consulting an instructor specialized in the field of qualitative research. The prospective teachers made their observations for 5 weeks and wrote their impressions in forms. For the face-to-face interviews, semi-structured interview forms composed of similar questions were used. The interviews were recorded upon permission; the researcher also took notes. Observations were performed with eight and interviews with three prospective teachers. The interview notes have been coded as A, B, C. The interviews lasted 90 min; 30 min for each. Of the teachers who were interviewed two observed in the first grade and one in the second grade.

Data analysis

Content analysis was used in the data analysis. For the content analysis, first the codes in the data set were found, then the themes taken from the codes were designated; the codes were arranged according to these themes. The themes were classified according to the research questions (Yıldırım and Şimşek, 2016: 253). Moreover, one-to-one extracts from the observation and interview results were placed at the end of each table.

Validity and reliability studies

For persuasiveness within the scope of validity (internal validity), interview data were arranged in the written form to provide participant confirmation and they were presented to the prospective teachers for agreement. To look into the research objectively and to provide consistency (inner reliability) or reliability in the research, a researcher who specialized in education and qualitative research was consulted for help in preparing the interview and observation forms. Furthermore, compatibility and consistence of method diversity –observation data and interview records and notes-, and observations of the researcher in the same environment twice have contributed to providing persuasiveness (inner validity) in the scope of validity. By using the formula: Reliability agreement number / agreement + agreement number for reliability, two researchers worked at different times for the same data and reached similar results; .86 was found (Miles and Huberman, 1994).

Data

In this section, the data are handled by the sub-problems of the research. In Table 2, the prospective teachers say that class teachers frequently have problems of language and communication contacts. During the observation results and interviews, it was surprising to see that the prospective teachers thought “teachers do not prepare distinctively for lessons” was not a problem for the Syrian students but a problem the teachers had. When the reason was asked during the interviews, the answer was like that:

“Although coming to class unprepared affects students negatively from the academic point of view, it returns to the teacher as a problem because it results in unwanted behaviors in class –doing other things because they cannot learn, talk to other students, and damage their peers etc.” (A, B-1st Grade).

Another aspect during the observations and interviews; as an answer to the question “What are the problems the teachers have?” they gave examples from the problems the Syrian students had. During the interviews, the answer given to the question “What does the teacher do in class?” is that:

“The teacher does not do anything different for the Syrians. At least I don’t see it. He places the Arabic and Turkish students side by side to realize peer learning and to enable them to learn Turkish. Thus, the Syrian students perceive the directions ‘like which page to open’ by following their Turkish peers. In addition, the teacher utilizes the Syrian students who speak Turkish as an interpreter to overcome the language problem” (B-1stGrade).

“The teacher teaches the whole class using the traditional methods. He does not invite the Syrian students to the board and does not ask them questions. The last two hours are for free-time activities. In those hours he deals with the Syrian students one by one.” (C-2nd Grade)

Upon the assessment of the statements it was clear that basically the problems are language issue and lack of empathy.

“

The teacher does not discriminate among the students; he does not pay special interest, either. The teacher does not deal with the students. He does not to pay too much attention. This situation is also difficult for the teachers because more than half of the students are Syrians. If a Syrian child writes correctly during dictation activities, local students face accusations such as

“I don’t believe you. Even the Arabs can write, you cannot, go and get to sleep.” This creates competition among the students. The teacher seems to have postponed the problem arising out of this. During our talks with the teacher, he said “they will learn with time. “It happened exactly like that. They are learning now though not in the first 2-3 weeks. They had great development. The children who couldn’t read and write can write very well now. It seems necessary to leave it to time. They read and write almost mechanically. When the teacher rewards or punishes, he does not discriminate as Turkish or Arabic. He doesn’t discriminate when taking their photographs and hangs them on the wall. The children thus have the sense of belonging. But one of the reasons for lack of communication between the Turkish and Syrian children is that the teacher compares them. The statement “

Even they have answered this. You go and get to sleep!” makes the Turkish students angry and so they complain to the teacher about Syrian students even for their small mistakes or make fun of them to leave them in a difficult position” (A-1st Grade). The teacher does not create any exceptions for the Syrian children. There is neither discrimination nor interest. The teacher remains neutral. If he has a special interest in the Syrian students, I think the Turkish students will feel discriminated. For this reason he remains unbiased. There is not a difference for them to understand the lesson. He interferes only when he sees mistakes” (C-2

nd Grade)

According to the observation and interview results of the prospective teachers in Table 3, it seems that Syrian students mostly have problems in terms of social-emotional development. They are exposed to ridicule because they do not speak/understand Turkish and they pronounce words in a wrong way. The situation they are in maims their self-confidence. Another interesting thing in the table is that the teacher allows competition in a multi-cultural class. In the interviews, it was explained that this competition was like “giving a star to the ones who wrote correctly during dictation activities and sharing their photographs in the WhatsApp class group.”

The main problem in Table 3 is also “not speaking Turkish.” This problem hinders their communication with their peers and their academic and social-emotional development. During the interviews after the prospective students said the teacher did not discriminate in any way, they added “When the teacher punishes somebody, he does it before all the students. He also uses physical violence, and gets angry. He does it to the Syrian students more frequently because his communication with them is a bit more broken when compared to Turkish students. They cannot express themselves. The teacher gets angry and hits, for them to supposedly, tell the truth. The child being hit is generally isolated from the class. They think the teacher doesn’t like him/her; we shouldn’t also like him/her. When the Turkish students are also hit; the class isolates them in the same way” (A, B-1st Grade).

“Syrian students have difficulty reading. Because Arabic is read from left to right, they read the Turkish texts in the same way. For example instead of “al” they read “la” (C-2nd Grade).

The B coded teacher candidate made this statement about the problems the Syrian students had:

“When two Turkish and Syrian students argue, the Turkish one tends to get even angrier and shouts. He gets angrier because he doesn’t understand the language he speaks and he thinks he has said swear words, thus he hits him more.The teacher brings them in front of the class, asks them to apologize and settles the situation. He punishes them whether they are Turkish or Syrian. He tells them to stand on one foot.” (B-1st Grade)

In Table 4, it is seen that the Turkish students also get irritated because they cannot communicate with the Syrian students. That means the Turkish children also have “language problem” in another dimension. At the interview, the trainee teachers stated that the Turkish students have more advantage than the Syrian students in terms of social and emotional development, saying that “the Turkish students feel that they belong to the environment. They think that they didn’t come there afterwards like the others. They feel they are the hosts. They are more powerful when

communicating with the teacher. I think their emotional connections are more powerful. The parents are more interested. They feel they are in a better position when compared with the Syrians” (A-1st Grade). The number of sub-themes is 2 “Language and Communication”. During the interviews the trainee teachers reported: “Even the poorest of the Turkish students are not at the bottom in class because one of the Syrian children is always the worst. This situation increases the self-confidence of the Turkish children.” (B-1st Grade)

From the academic point of view, the class teacher teaches the Syrian students who do not speak Turkish and he even invites them to his table and explains the subjects if they do not understand. This situation bores the Turkish students. Unwanted behaviors happen among bored students. During a two-week observation by the researcher, the 1st year teacher said:

“I had very successful students, but after the arrival of the Syrians, their families began to transfer them to other schools one after another because we could not do the teaching activities efficiently and intensively. We always had to start from the beginning and explain to the Syrian students several times. The parents transferred them to other schools because they did not want their children to fall behind. The language problem is also an annoying issue. Understanding and being understood which is fundamental for friendship relationships do not occur among the children. Because they do not understand what they say to each other, they even impose the worst meanings and show reactions.”

The solution proposals of the prospective teachers in Table 5 are under three topics namely “from the academic point of view”, “in terms of language and communication” and “from the social and emotional point of view”. The prospective teachers had proposals like “from the academic point of view, Syrian students should be taught in GEMs, courses should be opened in schools, teachers should learn Arabic, teachers should use body language for communication with the Syrian children, they should spend more energy in classes; in terms of language and communication, Turkish courses should be opened in the school, Turkish teachers should be recruited for the pre-school period; from the social and emotional point of view, welfare campaigns should be arranged.” The opinions of the prospective teachers are as follows:

A-coded trainee teacher said during an interview: “It is wrong to put the Syrian children among the Turkish children. There is not an intelligence problem. The biggest problem is language. If this is solved, it will be enough. The Syrians who speak Turkish learned it in the camps. Separate schools can be opened for Turkish or the number of class hours can be different. There can be supplementary courses. They don’t understand even if they can read. In my opinion, if they are to be in the same class, both the teacher and the families should support them. The families of the Syrians who are poor in class are not concerned. The teacher is more interested in the children whose parents come and talk to him.” (A-1st Grade).

“I would start a project in the school to teach Turkish to the Syrian children. Teachers who know both Turkish and Arabic should be the ones to teach them. The course should be at weekend or after school. In addition, there should be a supplementary center in the school. Turkish should be taught primarily.” (B-1st Grade)

“Attending the same class for Turkish and Arabic students causes the Turkish students to fall behind. They should follow the Turkish curriculum in the same school but in different classrooms” (C-2nd Grade).

The trainee teachers say they think it is important for the parents to talk to the teacher for the students even though they do not speak Turkish; they say they think the teacher would give more attention to the children whose parents are concerned.

In the research, it is concluded that the main problem is “language problem”. The Turkish teachers do not speak Arabic and the Syrian children do not know Turkish; they don’t understand each other and so the problems are not solved in time. This situation is reflected in the lesson, so the Syrian students cannot learn what the teacher teaches. Like every student who does cannot learn the lesson, they get bored and distract the other students and the teacher by displaying unwanted behaviors. Moreover, the class teachers do not implement facilitating activities nor bring varied material to class. Similar situations have been seen in the literature. It has been concluded that alien students do not understand their teachers, peers and the environment; they cannot communicate; they cannot express their feelings and thoughts; they do not participate in the lesson; and as a result of all these, they either have lower academic achievement as compared to their peers or frequently become unsuccessful (Güngör and Åženel, 2016). The following data have been reached: In a study related to the problems of the teachers who had refugee students, the main issue is the language problem; participating teachers do not design content for the need of the refugee students; teachers need material for those students; teachers do not develop objective methods in the process of assessment. It is a common idea that a preparatory training should be given to the teachers and refugee students for them to learn the Latin alphabet and Turkish. As a result of the research, it has been determined that teachers require vocational development and assessment aimed at refugee students such as analysis of the teaching content; teaching strategies; teaching aids; development and assessment of measurement material (Bulut et al., 2018; Erdem, 2017). Again the problems that the teachers came across and the themes that emerged according to the results of a study related to solution proposals are academic problems, language and communication problems, social problems and recommendations (ÅžimÅŸir and Dilmaç, 2018). In another study, the problems that emerged in classes that included Syrian children are gathered under three topics. These have been listed as an obstacle of language, lack of family support, and inefficiency of the teachers to have the refugee students grasp pedagogic skills (YaÅŸar and Amaç, 2018). A study on the problems of Syrian students in Turkey shows that the students were affected by post-traumatic stress disorder, had difficulty about understanding and communicating the content within the classroom, there were problems that arise due to the fact that the classrooms are overpopulated and teachers were not involved in decision-making processes about these students. Also, teachers are not effectively informed about refugee students as they are not in a credible effort to increase their capacity to cope better with the situation of these students (Tösten et al., 2017: 1149).

In the study, it has been concluded that the Syrian students cannot communicate with their surroundings and fall behind academically due to “the language problem”, live through lack of self-confidence and they are exposed to mockery of their classmates because they cannot express themselves properly. In a study related to Syrian students, it was reported that the biggest problem is that they do not speak Turkish and they have rapport problem with their peers; as for the problem the teachers who have Syrian students in their classes face is that they cannot communicate with the Syrian students and they cannot include them in the educational process (BaÅŸar et al., 2018; Kiremit et al., 2018). In a study related to the training of the Syrian refugees in the Child Studies Department of Ä°stanbul Bilgi University titled “The Situation of the Syrian Refugee Children at the State Schools” (URL, 2015), it was reported in the interviews with the teachers in the schools that discrimination and isolation were rare; but with the focused groups of students it was reported that there was very limited communication between the Turkish and Syrian students, no friendship experience and the Syrian children were influenced and isolated. Some children said the Turkish students did not play with them, did not believe what they said and did not make friends with them. Most of the children said they were satisfied with their teachers. It was observed that the teachers did not do anything to solve discrimination and isolation in schools. The teachers also stated that the problem of discrimination was related to the parents of the Turkish children. The parents did not want their children to sit with Syrian children, and the teachers said they had difficulty finding a place for the Syrian children to sit. The Syrian children were sitting either with another child or alone. It was observed that the teachers hesitated to take the initiative in this matter. In two different studies with the pre-school students, similar results were found. It was concluded that the level of the Syrian children to know Turkish played an important role in adapting to school, learning class rules, communicating easily with others and feeling secure (Yanık-Özger and Akansel, 2019; Avcı, 2019). It has been emphasized that in all similar studies, the most fundamental issue is language problem (Çerçi and Canalıcı, 2019; KüçüksüleymanoÄŸlu, 2018; Åžahin and Åžener, 2019). The studies having been done in this field and the consequences of this study are consistent. The most important problem experienced in a multicultural classroom was the “language problem”. The origin of most of the other problems such as academic failure, social and emotional adaptation problems is that they do not speak Turkish and do not understand what they hear.

At the end of the study, the fact that the teachers explain subjects at great length so that the Syrian students can understand and that they even deal with some children individually results in an important problem for the Turkish students. Because this situation slows down the progress of the subjects for the Turkish students, it is understood that it causes them to fall behind academically in comparison with their peers and also leads to unwanted behavior because they get bored. Similar results were found in a study carried out by Özdemir (2018). According to the data of this study with the topic “The Evaluation of the Opinions of the Turkish Students who Receive Education with the Syrian Students under Temporary Protection”, a great majority of the participants are unhappy to receive education together with the Syrian students and often fight with them because they cannot communicate with them.

In the entire research, “language problem” appears to be the main problem the Syrian children face. This problem influences the adaptation and academic situations, and the social and emotional developments of the students negatively. After the observations and interviews the prospective teachers suggested that students should certainly learn Turkish before they start school, there should be particularly language courses at school on weekdays and/or weekends, Syrian students should receive education according to the MEB (Ministry of Education) curriculum in separate classes from the Turkish students, teachers should learn Arabic, and Syrian students should attend in GEMs. In addition, if parents come to school and talk to the teachers, it will cause the teachers to pay more attention to the students. In a study related to the problems arising in schools where there are alien students, teachers reported that they try to solve the vocabulary-based language problem by using Google Translate, continuously have the children memorize poetry, visit houses to increase communication and understanding among students and have drama and game activities. Aiming at the solution of the problems they had with the alien students, teachers and administrators have suggested that primarily kindergarten training should be given, there should be language training intended for families and children, they should place them all in the same class not to affect the other children, and a new unit should be opened within the body of the Office of Education (SarıtaÅŸ et al., 2016). In another study, it was suggested that courses should be arranged for the teachers who have alien students in their classes in the field of Turkish teaching as a second and foreign language; permanent and temporary teachers should be appointed throughout the country to teach Turkish to the students and their families after school hours; counselling should be given to the students by appointing counsellors who speak Arabic and English;

Turkish courses should be designed for the families to have them participate in educational activities; seminars and school activities should be designed for the families to cooperate with the school and have more responsibility in the training of their children; placement tests should be given to the students for them to get appropriate education for their Turkish levels; the students, who cannot start school at the beginning of the term and especially those who are not efficient enough to read and write, should attend the first grade for a period of time or Turkish courses should be designed for them after school; teaching programs for Turkish lessons suitable for the students and orientation programs to school should be developed; more visual material should be provided for the students (Güngör and Åženel, 2018: 166-167). In a similar study, class teachers had the solution to the problems they had with Syrian students: Syrian students should attend separate classes, parents should be given father-mother training; after getting acquainted, classes should be joined and the elder students should attend different classes (Ergen and Åžahin, 2019: 377). In this and similar researches it has been concluded that for the education of Syrian students primarily “the language problem” should be solved (KardeÅŸ and Akman, 2018; SaÄŸlam and Kanbur, 2017; TaÅŸkın, 2018; Tunç, 2015; Weddle, 2018). We are of the opinion that the solution of this problem will contribute to the solution of several other problems.

In summary, according to this research, the most important problem experienced by both Syrian and Turkish students and classroom teachers is the problem of language. People who coexist together try to live and learn together without understanding each other. This leads to many academic, emotional and social problems. As a solution, teachers recommend that language courses be held for Syrian children before they begin their lives as a student. Germany is one of the countries that have experienced migration in the past years. During the migration events in Germany in 1980 and 1990, they placed migrant children in separate classes to teach them German as second language, which had significant negative effects on the school and business careers of migrant students. According to European experience from previous migrations, it has been found that taking migrant children into normal classes after teaching basic language skills is extremely important for socialization, active use of language and integration (Koehler and Schneider, 2019). Migration from Syria is still ongoing. The countries of the world have not developed a regulation to please the parties on the migration issue, to provide appropriate living conditions for Syrians and to bring the education of children to a level close to/equal to the standard of the children of the host country. As a result of the migration events so far, the majority of migrants have not returned to their home countries, even if everything improves. Investment in these children will benefit the host country in the long run (Koehler and Schneider, 2019).

The following suggestions have been introduced according to the results obtained from the research data:

1). Teachers who have alien students in their classes can get training in terms of how to teach in a multi-cultural class.

2). Applied training can be designed for teachers and counsellors to bring these war victim children back to life.

3). Teachers who have a second trauma can be supported by the government

4). Language courses suitable for their age and Turkish level can be started for Syrian children and adults to solve their language problem.

5). The training of “Teaching Turkish as a Foreign Language” can be given to the class teachers who have Syrian students in their classes.

6). Syrian parents can be encouraged to come to school and communicate with the class teachers.

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Avcı F (2019). Okul öncesi eÄŸitim kurumlarına devam eden mülteci öÄŸrencilerin sınıf ortamında karşılaÅŸtıkları sorunlara iliÅŸkin öÄŸretmen görüÅŸleri. Language Teaching and Educational Research (LATER) 2(1):57-80.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

BaÅŸar M, Akan D, Çiftçi M (2018). Mülteci öÄŸrencilerin bulunduÄŸu sınıflarda öÄŸrenme sürecinde karşılaşılan sorunlar. Kastamonu EÄŸitim Dergisi 26(5):1571-1578.

|

|

|

|

|

Buckner E, Spencer D, Cha J (2018). Between policy and practice: the education of syrian refugees in Lebanon. Journal of Refugee Studies 31(4):444-465.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bulut S, Kanat Soysal Ö, Gülçiçek D (2018). Suriyeli öÄŸrencilerin Türkçe öÄŸretmeni olmak: Suriyeli öÄŸrencilerin eÄŸitiminde karşılaşılan sorunlar. Uluslararası Türkçe Edebiyat Kültür EÄŸitim (TEKE) Dergisi 7(2):1210-1238.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Büyüköztürk Åž, Kılıç ÇE, Akgün ÖE, Karadeniz Åž, Demirel F (2018). Bilimsel AraÅŸtırma Yöntemleri. Pegem Akademi.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Chimienti M, Bloch A, Oppiopw L, Wihtol de Wenden C (2019). Second generation from refugee backgrounds in Europe. Comparative Migration Studies 7:40.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Crul M, Lelie F, Biner Ö, Bunar N, Keskiner E, Kokkali I, Schneider J, Shuayb M (2019). How the different policies and school systems affect the inclusion of Syrian refugee children in Sweden, Germany, Greece, Lebanon and Turkey. Comparative Migration Studies 7.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Çerçi A, Canalıcı M (2019). Geçici koruma kapsamındaki Suriyeli öÄŸrencilerin Türk eÄŸitim sistemine entegrasyon sürecinde yaÅŸadığı iletiÅŸim sorunları. Gaziantep Üniversitesi EÄŸitim Bilimleri Dergisi 3(1):57-66.

|

|

|

|

|

De Hoop J, Morey M, Seidenfeld D (2019). No lost generation: supporting the school participation of displaced Syrian children in

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lebanon. The Journal of Development Studies 55:107-127.

|

|

|

|

|

DillioÄŸlu B (2015). Suriyeli mültecilerin entegrasyonu: Türkiye'nin eÄŸitim ve istihdam politikaları. Akademik ORTA DOÄžU 10(1).

|

|

|

|

|

Emin MN (2016). Türkiye'deki Suriyeli çocukların eÄŸitimi temel eÄŸitim politikaları. Siyaset, Ekonomi ve Toplum AraÅŸtırmaları Vakfı (SETA), s.153.

|

|

|

|

|

Erdem C (2017). Sınıfında mülteci öÄŸrenci bulunan sınıf öÄŸretmenlerinin yaÅŸadıkları öÄŸretimsel sorunlar ve çözüme dair önerileri. Medeniyet EÄŸitim AraÅŸtırmaları Dergisi 1(1):26-42.

|

|

|

|

|

Ergen H, Åžahin E (2019). Sınıf öÄŸretmenlerinin Suriyeli öÄŸrencilerin eÄŸitimi ile ilgili yaÅŸadıkları problemler. Mustafa Kemal Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 16(44):377-405.

|

|

|

|

|

Guo Y, Maitra S, Guo S (2019). I belong to nowhere: Syrian refugee children's perspectives on school ıntegration. Journal of Contemporary Issues in Education 14(1).

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Güngör F, Åženel EA (2018). Yabancı uyruklu ilkokul öÄŸrencilerinin eÄŸitim - öÄŸretiminde yaÅŸanan sorunlara iliÅŸkin öÄŸretmen ve öÄŸrenci görüÅŸleri. AJESI - Anadolu Journal of Educational Sciences International 8(2):124-173.

|

|

|

|

|

Işıkdoğan UN, Kayhan N (2018). Teacher opinions on the problems faced in reading and writing by Syrian migrant children in their first class at primary school. Journal of Education and Learning 7(2)76-88.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kandemir H, KarataÅŸ H, Çeri V, Solmaz F, Kandemir SB, Solmaz A (2018). Prevalence of war-related adverse events, depression and anxiety among Syrian refugee children settled in Turkey. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 27:1513-1517.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

KardeÅŸ S, Akman B (2018). Suriyeli mültecilerin eÄŸitimine yönelik öÄŸretmen görüÅŸleri. Ä°lköÄŸretim Online 17(3):1224-1237.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kiremit RF, Akpınar Ü, Tüfekci AA (2018). Suriyeli öÄŸrencilerin okula uyumları hakkında öÄŸretmen görüÅŸleri.Kastamonu EÄŸitim Dergisi 26(6):2139-2149.

|

|

|

|

|

Koehler C, Schneider J (2019). Young refugees in education: The particular challenges of school systems in Europe.Comparative Migration Studies 7:28.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

KüçüksüleymanoÄŸlu R (2018). Integration of Syrian refugees and Turkish students by non-formal education activities. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education 7(3):244-252.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Miles MB, Huberman AM (1994). An expanded source book qualitative data analysis. (Second Edition). Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications.

|

|

|

|

|

Özdemir EB (2018). Geçici koruma altındaki Suriyeli öÄŸrencilerle birlikte eÄŸitim alan Türk öÄŸrencilerin görüÅŸlerinin deÄŸerlendirilmesi. Tarih Okulu Dergisi (TOD) 11(34):1199-1219.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Özer YY, KomsuoÄŸlu A, AteÅŸok ZÖ (2016). Türkiye'deki Suriyeli çocukların eÄŸitimi: Sorunlar ve çözüm önerileri.Akademik Sosyal AraÅŸtırmalar Dergisi (ASOS) 4(37):34-42.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Puri J, Aladysheva A, Iversen V, Ghorpade Y, Brück T (2017). Can rigorous impact evaluations improve humanitarian assistance? Journal of Development Effectiveness 9:519-542.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Rubinstein-Avila E (2017). Immigration and education: what should k-12 teachers, school administrators,and staff know? The Clearıng House 90(1):12-17.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

SaÄŸlam HÄ°, Ä°lksen KN (2017). Sınıf öÄŸretmenlerinin mülteci öÄŸrencilere yönelik tutumlarının çeÅŸitli deÄŸiÅŸkenler açısından incelenmesi. Sakarya Üniversitesi EÄŸitim Dergisi 2(7):310-323.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

SarıtaÅŸ E, Åžahin Ü, ÇatalbaÅŸ G (2016). Ä°lkokullarda yabancı uyruklu öÄŸrencilerle karşılaşılan sorunlar. Pamukkale Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 1(25):208-229.

|

|

|

|

|

Seydi AR (2014). Türkiye'nin Suriyeli sığınmacıların eÄŸitim sorununun çözümüne yönelik izlediÄŸi politikalar. Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi Fen-Edebiyat Fakültesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi 31:267-305.

|

|

|

|

|

Åžahin F, Åžener Ö (2019). Geçici koruma altındaki Suriyeli öÄŸrencilerin eÄŸitim süreçlerindeki dil ve iletiÅŸim sorunları: Ä°stanbul Fatih örneÄŸi.Avrasya Sosyal ve Ekonomi AraÅŸtırmaları Dergisi 6(9):66-85.

|

|

|

|

|

ÅžimÅŸir Z, Dilmaç B (2018). Yabancı uyruklu öÄŸrencilerin eÄŸitim gördüÄŸü okullarda öÄŸretmenlerin karşılaÅŸtığı sorunlar ve çözüm önerileri.Ä°lköÄŸretim Online 17(2):1116-1134.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

TaÅŸkın P, Erdemli Ö (2018). Education for Syrian refugees: problems faced by teachers in Turkey. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research 18(75):155-178.

|

|

|

|

|

Tösten R, Toprak M, Kayan MS (2017). An investigation of forcibly migrated Syrian refugee students at Turkish public schools. Universal Journal of Educational Research 5(7):1149-1160.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Tunç AÅž (2015). Mülteci davranışı ve toplumsal etkileri: Türkiye'deki Suriyelilere iliÅŸkin bir deÄŸerlendirme. Tesam Akademi Dergisi 2(2):29-63.

|

|

|

|

|

Tüzün I (2017). Türkiye'de mülteci çocukların eÄŸitim hakkını ve karşılıklı uyumu destekleyen yaklaşımlar, politikalar. European Liberal Forum.

|

|

|

|

|

URL (2020). Türkiye Göç Ä°daresi Genel MüdürlüÄŸü. Yıllara göre geçici koruma kapsamındaki Suriyeliler.

View

|

|

|

|

|

URL (2020). Mülteciler DerneÄŸi. Türkiye'deki Suriyeli Sayısı.

View

|

|

|

|

|

URL (2016). GEM'ler üç yıl içinde misyonunu tamamlayacak.

View

|

|

|

|

|

URL (2016). Suriyeli çocukların eÄŸitimi için yol haritası belirlendi.

View

|

|

|

|

|

URL (2015). Ä°stanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Çocuk Çalışmaları Birimi.

View 2.12.2018

|

|

|

|

|

Weddle DB (2018). An Amerıcan tune: refugee Chıldren In U.S. publıc schools. Kansas Journal of Law and Public Policy 27(3):434-456.

|

|

|

|

|

Yanık ÖB, Akansel A (2019). Okul Öncesi sınıfındaki Suriyeli çocuklar ve aileleri üzerine bir etnografik durum çalışması: Bu sınıfta biz de varız!. EÄŸitimde Nitel AraÅŸtırmalar Dergisi 7(3):942-966.

|

|

|

|

|

YaÅŸar MR, Amaç Z (2018). Teaching Syrian students in Turkish schools: experiences of teachers. Darnioji DaugiakalbystÄ— | Sustainable Multilingualism 13(1).

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Yıldırım A, ÅžimÅŸek H (2016). Sosyal bilimlerde nitel araÅŸtırma yöntemleri. Seçkin Yayınları.

|

|