ABSTRACT

Bullying and victimization remains a persistent phenomenon in schools within the United States of America. However, no studies have focused on bullying and victimization among deaf students. This cross-sectional study was conducted to determine the frequency of bullying and victimization among deaf children. Further, the study examined deaf children who could read and write at their respective grade levels or higher. Specifically, the possibility of these children experiencing distress linked to bullying and victimization was investigated, and whether the same level of distress varied steadily across grade levels. The study was conducted at eight U.S. residential schools for the deaf using the Reynolds Bully Victimization Scales for Schools. Twenty-one males and fifteen females participated in the study. Participants were sampled based on their reading and writing skills at fourth or fifth grade and above. There were 35 participants from 10th to 12th grade. Participants in 10th grade reported a significantly higher occurrence of bullying than those in 12th grade. Taken together, these findings indicated a strong correlation between victimization and total cases of distress, bullying, and levels of externalizing distress, as well as between victimization and the intensity of internalizing distress.

Key words: Victimization, bullying, deaf, residential schools.

Bullying is a major problem facing different schools and communities in the United States. According to Kaltiala-Heino et al. (2000), bullying includes negative actions by one or more persons directed toward a student or group. Bullying can exist in three forms: verbal, such as name calling and verbal threats; physical, like hitting and kicking; or relational, such as cyberbullying and twisting of information that has an emotional impact. These actions result in a power imbalance between the bully and victim(s). Among school-aged youths, bullying occurs within and outside of school buildings such as on school grounds, in cyberspace, and inside residence halls or dormitories for students attending residential schools. Students may find themselves involved in a bully-victim situation, wherein they are sometimes victims, and at other times bullies (Whitted and Dupper, 2005).

The aim of this cross-sectional investigation is to determine if residential schools utilize any assessment tools to identify victims of bullying, distress behaviors among victims of bullying, and potential bullies. This research also attempted to understand the prevalence of bullying and victimization cases among deaf youths. It should be noted that the term deaf will be used throughout this paper to refer to individuals who are Deaf, Hard of Hearing, Deaf Blind, and Developmentally Disabled Deaf. The study uniquely concerns high school students with 4th and 5th grade-level skills in reading and writing. Further, the study establishes whether distressful experiences among deaf students were related to bullying and victimization. Lastly, the study examines whether levels of distress varied steadily across grade levels in reading and writing.

Research questions

(i) Do residential schools for the deaf utilize the Reynolds Bullying Victimization Scale (RBVS; Reynolds, 2003) as an initial guide to assist with identifying potential bullies and victims?

(ii) Are there differences in distress between the victims and bullies attending the schools for the deaf?

Research hypothesis

Schools for the deaf are more likely to use RBVS to assist with screening potential bullies and victims due to the small scale of deaf individuals attending schools for the deaf. Students attending a residential school for the deaf will report being a victim of bullying. Additionally, a significant difference between victims and bullies reporting bullying and victimization is predicted.

Effects of bullying in schools

Numerous research studies have focused on the distressing impacts of victimization and bullying. In these studies, children involved in cases of harassment were observed as experiencing varying levels of distress either as victims or perpetrators. The symptoms of “internalizing problems” appeared to be subjective and internally experienced (Reynolds, 2003:4). Depression, withdrawal, sadness, anxiety, and insecurity are among the types of internalizing problems (Espelage and Holt, 2001). Victims of bullying may also experience feelings of loneliness and isolation as a result of lacking companionship (Bauman and Pero, 2011). Further, such problematic issues can cause an individual to transgress during adulthood. Although internalizing problems are internally experienced, victims may also exhibit or be at risk for externalizing problems characterized by overt behavioral indicators (Reynolds, 2003); impulsiveness, hyperactivity, and aggressiveness are some examples of these problems.

Moreover, victims may experience psychosomatic and other physical problems including irritable bowel syndrome, shaking and trembling, as well as headache, palpitations, panic attacks, cognitive difficulties, sweating, and somatic pain (Dake et al., 2003). Children bullying others have primarily been reported to experience problems related to externalizing behavior (Andrews et al., 2004). For example, bullies may develop behavioral challenges and even participate in antisocial activities (Baumeister et al. ,2008). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2009), reported that bullies have a high precedence of committing crimes later in life. In one study, it was discovered that approximately 25% of bullies develop criminal records before the age of thirty.

Smoking and drinking alcohol are other behaviors that bullies tend to exhibit at a young age (Hodgdon, 2005). In the environment of learning institutions, bullies are more likely to carry weapons compared to victims (Bear et al., 2015). Victims have been reported to face adopting complications such as digestive disorders. As indicated in different studies, children who are bully-victims experience higher levels of anger and depression compared to all other youths (Crocker and Quinn, 2000). Comparisons between victims or bullies and bully-victims indicated that bully-victims are more likely to display externalizing behavior and be referred for specialized psychiatric care. Involvement in bullying and victimization leads children to experience distress that can be harmful and disturbing to their well-being. Loss of self-esteem is an unpleasant experience for both victims of bullying and perpetrators.

Bullying and deaf students

According to the literature, the occurrence of bullying and victimization among the deaf and their hearing counterparts has been studied. Specifically, studies demonstrated how the deaf might experience additional stressors including school-related changes, such as being transferred from a residential school to a mainstream learning center or vice versa (Kent, 2003).

Currently, there are no studies that examine the occurrence of bullying, victimization and distress experiences among students with grade-specific reading and writing capacities who attend residential schools for the deaf. Such studies would likely have significant implications.

Various research has been conducted on bullying over the years, yet very little has been discovered in cases of harassment among deaf youths. Taylor et al., (2010) discovered students with disabilities, such as learning disabilities and emotional problems, to be in greater danger of being bullied. Consequently, students with disabilities were also deemed potential bullies and bully-victims as compared to nondisabled students. Flynt and Morton (2004) further realized that students with emotional, developmental, and behavioral problems were twice as likely to bully victims, three times as likely to intimidate other individuals, and three times more likely to become bully-victims than those without such special needs. These study findings were parental report-based using documentation of the children’s conduct and health.

A recent focus of research has been on cases of bullying among children in the special education system. Specifically, these studies examine bullying among children with autism spectrum disorders, language impairments not related to hearing loss, and intellectual disabilities. The researchers discovered bullying among students with special needs that was often tied to their social skills deficits, disciplinary practices, and additional mental health diagnoses (Hodgdon, 2005). Additionally, findings from previous studies validated an increasing prevalence of bullying during a student’s mid-school years that declines in the high school years (Hong and Espelage, 2012). Moreover, gender differences in bullying and victimization were well-defined by the demographics of the communities in which the students lived; some research suggested that girls were more likely to experience relational victimization than boys, while the same males were more likely than girls to be physically victimized (Baumeister et al., 2008).

Few researchers have thoroughly addressed bullying and victimization among deaf youths. Most studies focus on the issue of bullying itself among children who are deaf; however, no research provides insight into the possible tools and resources that could be utilized to identify bullies and victims in schools with the deaf youths. Therefore, based on currently established findings, it is hypothesized that bullying and victimization will occur less among 10th grade students with a minimum of 4th grade-level reading and writing skills. It is also hypothesized that 12th graders will experience lower levels of distress as compared to other participants.

Participants

At the time of the study, 48 residential schools for the deaf were still operating within the U. S. Students resided at the schools Monday to Friday and went home on the weekends. To recruit participants, the researchers contacted 24 of these schools on the East Coast, in the Midwest, and the South. In agreement with the administrators of the schools, the researchers were permitted to conduct the study, but the school names and exact locations were not to be identified in this report. Initially, 69 students were recruited to participate in the study, but only 35 met the eligibility criteria. Participants included male and female students, aged 15 to 21 years (M=15.22, SD=3.45), who were required to have at least 4th or 5th grade reading and writing abilities. Of these students, 15 were in 10th grade (n = 15), 13 were in 11th grade (n = 13), and 7 students were in 12th grade (n = 7).

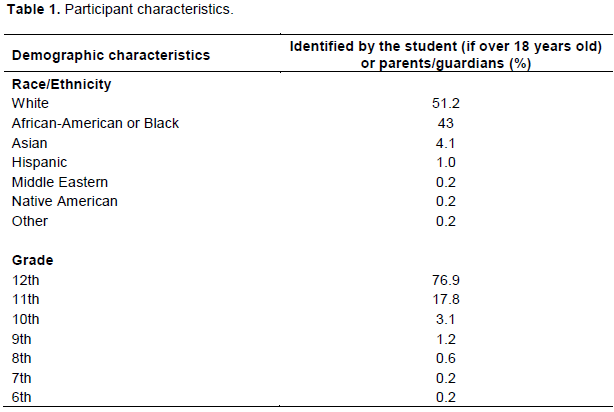

Within this group, 51.2% of the participants or their parents/guardians (if below 18 years old) identified themselves as White, 43% African-American, 4.1% Asian (includes South Asian), 1.0% Hispanic, 0.2% Middle Eastern, 0.2% Native American, and 0.2% other/ declined to answer. Additionally, the majority of the students (76.9%) were in 12th grade. Table 1 gives a breakdown of participants by grade level.

Procedure

Soon after approval from the University’s Institutional Review Board and the school’s administration, we requested that the institution’s coordinator send home the Parent Information Sheet (Appendix D), Voluntary Assent Forms (Appendix F), and Parental Consent Forms (Appendix E) to students able to read and write at 4th or 5th grade levels. Parental consent was required for students below the age of 18, along with signatures from their parents or guardians. Students over the age of 18 personally returned the consent and assent forms to their teachers and research coordinators at their relevant schools. The forms were then transferred to us during the data collection phase. All students were given between one and two weeks to return their forms.

Data collection occurred in the morning from 9:00-11:00 a.m. to ensure student alertness and motivation in filling out the research instrument. Participants met in groups in the school counselor’s office, principal’s cottage, or the assessment classroom. The same procedures were followed in every data collection meeting. Only students obtaining parental consent and providing assent for the exercise were permitted to participate. After introducing ourselves, each participant received a packet containing a Reynolds Bully Victimization Scale (RBVS) and a Reynolds Bully Victimization Distress Scale (BVDS; Reynolds, 2003), as well as the study instructions based on the RBVS manual. We explained that in cases where one of the researchers had to be absent while conducting the study at another school, alternate staff would assist in data collection. We also emphasized our policies regarding confidentiality and protection of research participants; none of the participants were to disclose the school’s name and state where other researchers were conducting the study.

Materials

The assessment tools in this study were the RBVS, which includes the BVS and the BVDS (Reynolds, 2003). The RBVS was designed for use in studies with children and adolescents aged 7 to 20 years. These scales were appropriate to the study aims which involve measurement of bullying and victimization among peers within and near schools. Each of the 46 items on the BVS includes the following four response choices: 0 points (never), 1 point (once or twice), 2 points (three or four times), and 3 points (five or more times). There are two different scales within the BVS: Bullying and Victimization. Both scales assess experiences among youths occurring in the past month. The Bullying Scale ranges from interactive aggression and harassment to overt peer hostility. The Victimization Scale includes assessments on respondent experiences with peer victimization such as physical assaults, forced action, being spat on, threatened with harm, being chased, being called names, intimidation, and being teased.

The BVS can be a group administered tool, taking between 5 and 10 minutes for a child to complete. The raw data gathered in the tool as scores are converted to t-scores that are characterized by a standard deviation (σ) of 10 and a mean of 50. The normal range includes t-scores falling below 58, while the clinically significant range comprises t-scores between 58 and 65 on the bullying scales. Scores between 66 and 74 are explained as those falling in the moderately severe range, while the severe range includes scores above 75. Children scoring within or above the moderately severe range on their questionnaire reports are considered to have engaged in frequent bullying.

Similarly, the t-scores from the victimization scale can be interpreted with different sets of meanings. T-scores below 56 fall within the normal range, while the clinically significant range includes scores between 56 and 63, with scores from 64-68 falling within the moderately severe range; scores of 69 and above are in the severe range. Children scoring in or above the moderately severe range would have encountered frequent victimization experiences which place them at higher risk for societal and emotional challenges.

The BVDS was used to measure psychological distress from the past month as a result of victimization (Reynolds, 2003). The BVDS includes 35 items, each containing four responses: 0 points (never or almost never), 1 point (sometimes), 2 points (a lot of times), and 3 points (almost all the time). Within the BVDS, there is an Externalizing Distress Scale which assesses externalizing issues such as anger, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder. It also has an Internalizing Distress Scale assessing internalizing concerns such as misery, anxiety, depression, and hopelessness. As with the BVS, the BVDS raw scores are converted to t-scores with a standard deviation of 10 and a mean of 50. Scores below 61 on the Externalizing Distress Scale are in the Normal range, while those ranging between 62 and 67 are in the Clinically Significant range. Scores in the Moderately Severe range vary between 68 and 75. The Severe range scores are above 76. From different analyses, children scoring within the Severe range may display anger toward students who bully them and engage in violent activities.

On the Internalizing Distress Scale, the Normal range includes scores lower than 59. Scores ranging between 60 and 64 fall within the Clinically Significant range. Scores from 65-74 are within the Moderately Severe range, while those scoring above 75 are considered to be within the Severe range. Students scoring within the Moderately Severe range or above may regularly experience high levels of distress. The Total Distress Scale provides another means of student comparison, with scores below 56 within the Normal range, scores of 57-63 within the Clinically Significant range, scores from 64-70 falling within the Moderately Severe range, and the Severe range includes those whose scores exceed 71. The BVDS can be administered to children in groups, taking approximately 5 to 10 minutes to complete. When Reynolds standardized the BVDS and BVS, the raw scores were converted to comparable t-scores with a standard deviation of 10 and a mean of 50. The RBVS Manual provides full details of his method, as well as the standardization, validity, and reliability of the BVS and BVDS (Reynolds, 2003).

These study instruments were standardized through 2000 American students gathered from 37 schools and 11 states. The study sample was stratified through sex, race, parent educational levels, grade, and age, based on the 2000 U.S. census data. Evidence of the reliability and validity of BVS and BVDS could be found in the Bully Victimization Reynolds Scales for Schools manual, pg. 61. The validity for the BVS and BVDS was determined for this study; content validity was established using the item-total scale correlations obtained from the standardized sample as it was crucial in determining the capacity of the scale to represent the content of the domain being measured.

It was hypothesized that a higher prevalence of bullying would be found among 10th graders as compared to their 12th grade counterparts. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of victimization between 10th, 11th, and 12th grade students. However, it was discovered that 4.6% (n = 3) of the study participants were bullies, based on the results of the BVS scores which ranked them in the Moderately Severe range; 8.6% were victims (n = 3); and 2% of them (n = 1) were discovered to be bully-victims.

The study also investigated distress experiences among participants to establish if they varied systematically across the 10th, 11th, and 12th grades. It was postulated that 12th graders would experience lower levels of distress compared to students from other grades. However, no influence from grade level was found on the overall internalizing or externalizing levels of distress related to victimization. Based on the results, it was apparent that our sample had not experienced as many social life disruptions throughout elementary and middle school transitions as educators had feared. Additionally, our results appeared to support those findings delivered by other special education researchers related to bullying (Blake et al., 2014), suggesting that youths living with special needs may have resilient qualities that help them endure transitions between grade levels.

The RVBS measured bullying behavior and victimization among peers in schools for the deaf. In this study, we used the BVS and BVDS; the School Violence Anxiety Scale, also part of the RVBS, was not used. Despite the limited data, school violence does not appear to be an issue in schools for the deaf. However, bully-victim situations are frequently discussed among educators of deaf students (Bat-Chava, 2000). The BVS measures a range of bullying behaviors, including those that are symptomatic of overt peer pressure, harassment, and aggression. The BVDS consists of the Internalizing Distress Scale and the Externalizing Distress Scale and provides a BVDS total scale score. These scales were used to appraise the level of psychological distress specific to individuals being bullied.

This project was approved by the appropriate university institutional review board. The data was gathered in Fall 2017, Spring 2018, and Summer 2018. The researchers contacted 24 schools. The schools were selected based on the researchers’ ease of transportation as this project was not grant funded. Therefore, the researchers used personal funds to avoid delaying the project by waiting one or two years to re-apply for grants. Many schools were unable to accommodate the researchers due to their reaccreditation experience, reduction in the school’s budget that promoted the absence of students with 4th or 5th grade reading and writing skills, having interim administrators, and lack of interest in research.

The schools for the deaf expressed to the researchers that they would prefer “tried and true” solutions to bullying rather than research with an unfamiliar assessment, and they are facing the unfortunate reality of the residential school being on the brink of closure by the state. Depending on their reading fluency, students required between 45 minutes and 1 hour to terminate the assessment instruments. The researchers completed the review of all parental consent forms for students under age 18, referrals of bullying or bully-victimization school records approved for release by the school’s administration, and instructions for the assessment instruments. Once the data was entered in SPSS, the .80 criterion was used in assessing inter-rater reliability. The inter-rater reliability was excellent.

Other factors not included in the research

Both researchers are deaf and fluent in American Sign Language (ASL). After each testing session, participants were informed that they were free to ask questions or express any concerns after the testing. In schools that did not have school counselors fluent in ASL, or no school counselor (some schools had a behavior specialist, an advocate, or a family and school social worker instead of a school counselor), students expressed that they had many emotional scars from previous grades or previous schools. Further, several students transferred to the residential school for the deaf from a mainstream school. These students expressed great sadness, anger, and disappointment with their former mainstream schools, demonstrating that they had been holding onto these emotions for years with few outlets to express themselves and move forward. Students who joined residential schools starting in elementary or middle school indicated the presence of bullying during middle school years, much more than they experienced in high school. Another factor was that students felt bullied by classroom teachers who were either hearing and believed in SIM-Com (speaking and signing at the same time), or native ASL users from well-known deaf families in their communities insensitive to the students’ lack of near-native ASL skills. The students reported these two factors as stressors.

This study had several limitations. The small sample size (N = 35) raises a question about the degree to which the results can be generalized to all students with the same characteristics in other residential schools for the deaf in the same state and other ones nearby. Additionally, a relatively equal number of 10th and 11th graders and a smaller number of 12th graders participated in the study; therefore, the results from the 12th-grade sample should be interpreted with caution. If this stratified random sample had been implemented across grade levels, the inclusion of an equal number of students from each grade may have resulted in a more balanced representation. However, a stratified random sample would have been difficult to implement given the small population of students with special needs considered in the study. Additionally, not all parents permitted their children to participate in the study.

Another significant limitation is the narrow construct of the Reynolds BVS and BVDS within the context of this study. For example, cyber-bullying was not accessed from the BVS; thus, the data provided was inconclusive. It is possible that some students cyber-bullied others or were bullied and experienced victimization resulting from cyberbullying, but such information was neither solicited nor reported in the study. Additionally, the questions on the BVDS only explicitly ask about distress related to victimization, not bullying. Further, it was possible that the self-stated bullies could have been distressed at higher levels than they reported through the BVDS.

IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY

In addressing problems related to bullying and victimization, it is important to use preventive measures and interventions to help promote and restore mental and emotional health. If bullying and victimization cases increase, personnel from every school should deliberate on implementing or re-implementing school-wide bullying prevention programs such as the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (2003). In the study of deafness, previous studies have been conducted on the OBPP which have contributed to its status as a “model program,” and part of the violence prevention initiatives as reinforced by the Department of Justice (Olweus and Limber, 2003). The San Francisco based non-profit program, No Bully (developed in 2009) or Izzy Kalman’s Bullies to Buddies (2010), are other programs applicable in anti-bullying efforts.

If the results obtained from school screening indicated relatively low bullying and victimization rates, it would become unnecessary to establish other large-scale bullying programs. Current research, including this study, shows a strong association between internalizing distress and cases of victimization in addition to externalizing and bullying distress (Carter and Spencer, 2006; Taylor et al., 2010; Rivers and Smith, 1994; Vernberg et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2016; Olweus and Limber, 2003). Administrators have a responsibility to take action as an essential measure upon suspicion of students being victimized or acting as bullies (Rigby, 1995). Individual counseling or group psycho-educational counseling should be given to such students, while social skills training would be effective once they focus on bullying avoidance behaviors and a coping mechanism to manage the negative impacts of bullying.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FURTHER STUDY

It is recommended that other researchers conduct studies like this one, considering the benefits to society they would offer by providing further evidence of using bullying and victimization assessment tools to identify potential bullies and victims. Further, it may be of help for educators to remain conscious of the effects of victimization among children with special needs. It is recommended, however, that future researchers modify their procedures when conducting similar studies. Finally, the addition of a hearing comparison group maybe of greater benefit than making direct comparisons among individuals in the same age group and population.

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Andrews JF, Leigh I, Weiner MT (2004). Deaf people: Evolving perspectives from psychology, education and sociology. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

|

|

|

|

Bat-Chava Y (2000). Diversity of deaf identities. American Annals of the Deaf 145(5):420-428.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Bauman S, Pero H (2011). Bullying and cyberbullying among deaf students and their hearing peers: An exploratory study. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 16(2)::236-253.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Baumeister AL, Storch EA, Geffken GR (2008). Peer victimization in children with learning disabilities. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 25(1):11-23.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Blake JJ, Banks CS, Patience BA, Lund EM (2014). School-based mental health professionals' bullying assessment practices: A call for evidence-based bullying assessment guidelines. Professional School Counseling 18(1):136-147.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Carter BB, Spencer VG (2006). The fear factor: Bullying and students with disabilities. International Journal of Special Education 21(1):11-23.

|

|

|

|

Crocker J, Quinn D (2000). Social stigma and the self: Meanings, situations, and self-esteem. In: Heatherton T, Kleck RE, Hebl MR, Hull JG (Eds.), The social psychology of stigma (pp. 153-183). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

|

|

|

|

Dake JA, Price JH, Telljohann SK (2003). The nature and extent of bullying at school. Journal of School Health 73(5):173-180.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Espelage DL, Holt MK (2001). Bullying and victimization during early adolescence: Peer influences and psychosocial correlates. Journal of Emotional Abuse 2(2-3):123-142

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Flynt SW, Morton, RC (2004). Bullying and children with disabilities. Journal of Instructional Psychology 31(4):330-333.

|

|

|

|

Hodgdon P (2005). Bullying and victimization among middle school students in residential schools for the deaf: program implications (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Gallaudet University, Washington, D.C.

|

|

|

|

Hong JS, Espelage DL (2012). A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: An ecological system analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior 17(4):311-322.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Kaltiala-Heino R, Rimpelä M, Rantanen P, Rimpelä A (2000). Bullying at school-An indicator of adolescents at risk for mental disorders. Journal of Adolescence 23(6):661-674.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Kent BA (2003). Identity issues for hard-of-hearing adolescents aged 11, 13, and 15 in mainstream setting. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 8(3):315-324.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Olweus D, Limber S (2003). Blueprints for violence prevention: Bullying Prevention Program. Boulder, CO Institute of Behavioral Science.

|

|

|

|

Reynolds WM (2003). Bully victimization: Reynolds scales for schools. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Rigby K (1995). What schools can do about bullying. The Professional Reading Guide for Educational Administrators 77(1):1-5.

|

|

|

|

Rivers I, Smith PK (1994).Types of bullying behavior and their correlates. Aggressive Behavior 20(5):359-368.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Taylor LA, Saylor C, Twyman K, Macias M (2010). Adding insult to injury: Bullying experiences of youth with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Children's Health Care 39(1):59-72.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Vernberg EM, Nelson TD, Fonagy P, Twemlow SW (2011). Victimization, aggression, and visits to the school nurse for somatic complaints, illnesses, and physical injuries. Pediatrics 127(5):842-848.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Whitted KS, Dupper, DR (2005). Best Practices for Preventing or Reducing Bullying in Schools. Children and Schools 27(3):167-175.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Zhang A, Musu-Gillette L, Oudekerk BA (2016). Indicators of school crime and safety: 2015 (NCES 2016-079/NCJ249758). National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, and Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Washington, DC.

|