ABSTRACT

Previous research demonstrated that the marketing strategy of ingredient branding can enhance brand value, whilst enlarging outcomes for the value chain. Although, African-ingredient branding—using commodities produced/grown in Africa as a product attribute—has been considered theoretically, it has never been explored experimentally. It is therefore unclear whether this particular marketing strategy could increase brand equity. By conducting two experimental studies, this research work explores whether African-ingredient branding can enhance the evaluation of food items by export-market consumers and examines whether the strength of host brands and/or attitudes towards specific African countries of origin might also influence consumer evaluation processes with regard to African-ingredient branded products. The results reveal that African-ingredient branding is a valuable marketing strategy, which can have a positive influence on the evaluation of food items by export-market consumers. They further illustrate that evaluations of these products are only affected by the strength of the host brand, suggesting that the strategy is more effective for strong brands than for weak brands. Consumer attitudes towards specific African countries are apparently not decisive for their evaluations of hedonic products branded according to African ingredients. The research work provides primary experimental evidence of the positive effects of African-ingredient branding as a valuable marketing strategy, indicating theoretical and practical-normative implications, as well as suggestions for future research.

Key words: Marketing, ingredient branding, African-ingredient branding, export-market consumer.

Globalisation has grown rapidly, making it possible for consumers to buy products and goods from all over the world (Kotler and Keller, 2016). In particular, food items are often produced or at least processed in several countries before reaching their end-users. These developments in the value chain are rooted predominately in technological innovations (particularly in the area of agriculture), advances in the field of transportation and organisational innovations (Ietto-Gilles, 2019: 155). Whereas these advancements have translated into increased revenue, profit and return on investment for intermediaries and manufactures, the producers and farmers in developing countries who work hard to produce the commodities for a globalised market receive only a small fraction of the realised retail prices (Sigué, 2012). Accordingly, alternatives are needed to increase the overall value shares of products and goods, especially in frontier-country markets, including those in many African countries (Dadzie and Sheth, 2020).

Against this background, previous studies have suggested various marketing strategies for adding value to brands, including ingredient branding (Ponnam et al., 2015a), which can generate opportunities for improving the welfare of farmers and reducing poverty whilst increasing overall profit throughout the value chain (Kotler and Pfoertsch, 2010; Sigué, 2012). Ingredient branding can be defined as a form of co-branding, in which critical attributes (ingredients or commodities) of one brand are incorporated into another brand, with the branded ingredients appearing on the product (Kotler and Pfoertsch, 2010; Leuthesser et al., 2003). In line with existing evidence (Desai and Keller, 2002) that ingredient branding is an appropriate marketing strategy for strengthening added value for consumers whilst increasing the overall value of a product, service or good, the present research work investigates whether commodities grown/produced in Africa could also be used as an ingredient branding marketing strategy for positively influencing the perceptions and evaluations of export-market consumers with regard to food items and hedonic products; thus adding value to the host branded product or good. The export-market consumers are defined as high-income consumers in developed markets.

Accordingly, the current research aims to experimentally investigate whether the ingredient branding of commodities grown/produced in Africa could be used to have a positive influence on the ways in which export-market consumers evaluate food items and hedonic products. To this end, two studies were conducted. The first study (study 1) investigates whether African-ingredient branding can influence the evaluation and perception of food items by export-market consumers, as theoretically assumed (Papadopoulos and Hamzaoui-Essoussi, 2015; Sigué, 2012). The second study (Study 2) explores the impact factors that influence the evaluation processes of export-market consumers. Specific attention is focused on the impact of the strength of the host brand and consumer attitudes towards the specific African countries in which the commodities are grown or produced.

Branding, co-branding and ingredient branding

Brands have been identified as a key influencing factor that determines success in a global economy (Sigué, 2012, Kathuria and Gill, 2013; Lee, O’Cass and Sok, 2017; Keller and Brexendorf, 2019). One fundamental marketing instrument is brand equity, which is defined as the added value that a brand can give to a product, service or good (Faquhar, 1989). More generally, branding can be defined as the process by which manufacturers help consumers to differentiate offerings on a highly dynamic market, thereby enabling consumers to develop specific associations and feelings towards a brand and its associated product (Webster and Keller, 2004).

Co-branding involves the combination of two or more brands in a single product (Desai and Keller, 2002). It is known to be effective in leveraging strong brands (Leuthesser et al., 2003). As a form of co-branding, ingredient branding involves the incorporation of critical attributes of one brand into another (Ghodeswar, 2008; Ponnam et al., 2015a). For example, displaying the ingredients that have been used can strengthen a product and improving its brand equity (Desai and Keller, 2002; Keller, 1998). According to Kotler and Pfoertsch (2010), labelling or even simply marking the components of a product is sufficient to be qualified as ingredient branding. The success of ingredient branding is, however, dependent on the consumer’s values, the consumers’ involvement and fit between the host brand and the branded ingredients (Desai and Keller 2002; Dalman and Puranam, 2017; Vaidyanathan and Aggarwal, 2000). Previous studies have demonstrated that ingredient branding facilitates the transfer of the positive associations and goodwill of an ingredient to the host brand, thus enhancing the equity of the brand, and therefore the product (Desai and Keller, 2002; Ponnam, Sreejesh and Balaji, 2015a). The host brand can, consequently, integrate the features and capitalise the brand associations of the ingredient to increase the market competitiveness and market shares. The strength of a branded (or ingredient-branded) product has, therefore, a significant influence on the intra-individual value of the product and, consequently, the consumers’ product evaluations and the associated decision-making process (Dalman and Puranam, 2017; Radighieri et al., 2014). A fact that has been confirmed by a recently conducted survey, indicating that 73% of export-market consumers (American, European and Asian consumers) expressed that they would pay more for a product with ingredients they know and trust (Gore-Langton, 2016). Suppliers and/or producers thus have an incentive to make these ingredients visible to consumers as means of increasing the value of their products (Keller, 2003; Kotler and Pfoertsch, 2010). Moreover, in light of the current societal demand for sustainable products and goods, it might be even more important to help consumers make sustainable decisions by displaying both the ingredients used and the way in which they were produced and traded. Against this background, it should be evident that ingredient branding enhances brand awareness and the image for host products, thereby leading to favourable brand evaluations (Kotler and Pfoertsch, 2010). Considerable research attention has been devoted to investigate ingredient branding in various contexts (in the food market (Kanama and Nakazawa, 2017) or for luxury brands (Moon and Sprott, 2016) whilst promoting the application of innovative technology to develop and manage brands (Rodrigue and Biswas, 2004; Tepic et al., 2014; Ponnam et al., 2015a). To date, however, little is known about the specific influence of commodities grown and produced in Africa as part of a marketing strategy based on African-ingredient branding (Papadopoulos and Hamzaoui-Essoussi, 2015; Sigué, 2012).

African-ingredient branding

The process of globalisation and the associated expansion of global trade flows (especially in the agricultural and food markets) have made the origin of food items a crucial attribute in the evaluations of consumers, as well as in their subsequent buying decisions (Al-Sulaiti and Baker, 1998; Beverland and Lindgreen, 2002; Aichner, 2014; van Ittersum, Candel and Meulenberg, 2003; Oberecker and Diamantopoulos, 2011; Herz and Diamantopoulos, 2017; Verlegh, Steenkamp and Meulenberg, 2005; Winit, Gregory, Cleveland and Verlegh 2014). In the past, the country of origin tended to be particularly important in the absence of other information about a product, good or service (Al-Sulaiti and Baker, 1998; Bilkey and Nes, 1982; Keller, 1998; Luomala, 2007). Currently, however, the country of origin is likely to act as an indicator (or factor in the evaluation) of the quality, social impact or sustainability of specific products or goods (Lorenz et al., 2015; Hsu et al., 2017). In this regard, based on the fact that the African continent is home to a diversity of natural and cultivated agricultural products and goods, due to its varied climatic, edaphic and topographical features (Goldblatt, 1997), African commodities might be associated with various positive attributes, whilst having a potentially positive influence on the perceptions that consumers have of specific products. This could help to infuse the positive attributes of African ingredients into a host brand, thus strengthening and enhancing the value of the brand’s products (Kanama and Nakazawa 2017; Kotler and Pfoertsch, 2010).

Despite the potentially positive influence of African commodities, they might also be subject to negative connotations, due to the association of some African countries with crime, war and social/environmental disasters. One example in this context is offered by Mali, which has recently been the centre of negative media attention. Following its civil war (2012-2013), Mali has suffered from severe attacks by Islamic fundamentalists, leading to the closure of more than 500 schools and causing people to flee from their towns. It is thus likely that some specific African countries could elicit negative associations in consumers, and this could affect their product evaluations. In addition to the impact of specific countries of origin (Aichner, 2014; Al-Sulaiti and Baker, 1998; Kinra, 2006; Luomala, 2007; Verlegh and van Ittersum, 2001), the characteristics of host brands apparently have an influence on consumer-evaluation processes (as mentioned before).

Theory of consumption values

In addition to the influencing factors mentioned above (such as specific countries of origin, strength of the host brand), consumers obviously judge quality according to a variety of informational cues that they associate with specific products, goods and services (Keller, 1993; Zeithaml, 1988). Therefore, consumers use an inferential transfer process by which they evaluate a new offering based on what they already know, feel or have experienced with the brand or the ingredient (Vaidhyanathan and Aggarwal, 2000; Czellar, 2003; Desai and Keller, 2002; Jongmans et al., 2019). More precisely, consumers use values as implicit criteria for forming preferences and evaluations, and these values serve to guide their actions, attitudes, judgments and comparisons between specific objects and situations (Holbrook, 1999; Long and Schiffman, 2000; Gallarza et al., 2011).

One theoretical model that is frequently applied to investigate the consumer-evaluation process and its associated values is the ‘theory of consumption values’ proposed by Sheth et al. (1991). The theory distinguishes five dimensions that have an impact on consumer-choice behaviour with regard to products, goods and services: (i) social, (ii) epistemic, (iii) emotional, (iv) functional and (v) conditional values. The social values of a product, good or service are defined as the perceived utility acquired from a product, as associated with one or more specific social groups (Sheth et al., 1991). The epistemic value of a product, good or service refers to its capacity to arouse curiosity, provide novelty or satisfy a desire for knowledge (Sheth et al., 1991). A product’s capacity to arouse feelings, moods and emotions are related to its emotional values (Sheth et al., 1991). This is composed of the utility derived from the perceived quality and expected performance of a product (Sheth et al., 1991; Van Riemsdijk et al., 2017). Functional values have been identified as the primary determinant of consumer choices (Gonçavles et al., 2016).

The fifth dimension proposed by Sheth et al. (1991), conditional values, refers to the perceived utility of a product, good or service in a specific situation or set of circumstances. It has therefore not been taken into consideration for this study, given that the experimental situations of the participants remained the same. The four other dimensions of the theory of consumption (Sheth et al., 1991) are considered when estimating the effects of African-ingredient branding and its associated repercussions on the perception levels of export-market consumers.

Research approach and hypotheses

Based on the results of previous researches (Aichner, 2014; Keller, 2003; Kotler and Pfoertsch, 2010; Luomala, 2007; Sigué, 2012; Papadopoulos and Hamzaoui-Essoussi, 2015), the overarching research question for the current investigation concerns whether African-ingredient branding can influence the perceptions of export-market consumers, thereby shaping their evaluations of food items and hedonic products. The investigation focuses on the effects of such branding on both general and specific dimensions (Sheth et al., 1991). The first study in this investigation explores the impact of African-ingredient branding on the general product evaluations and specific consumption-value evaluations of export-market consumers, according to a questionnaire-based experiment.

Study 1: African-ingredient branding as a valuable marketing strategy

Previous studies have suggested that ingredient branding (Rodrigue and Biswas, 2004; Tepic et al., 2014) is effective in enhancing brand equity. To the authors’ best knowledge, however, the impact of African-ingredient branding on the general product evaluations of export-market consumers has been investigated only at a theoretical level (Sigué, 2012), with no experimental examination. The first study in this research work therefore applies an online questionnaire-based experiment to explore whether African-ingredient branding increases brand equity. The underlying hypothesis is as follows:

H1: African-ingredient branding has a significant influence on consumers’ general evaluations of food items.

Study 1

Stimuli

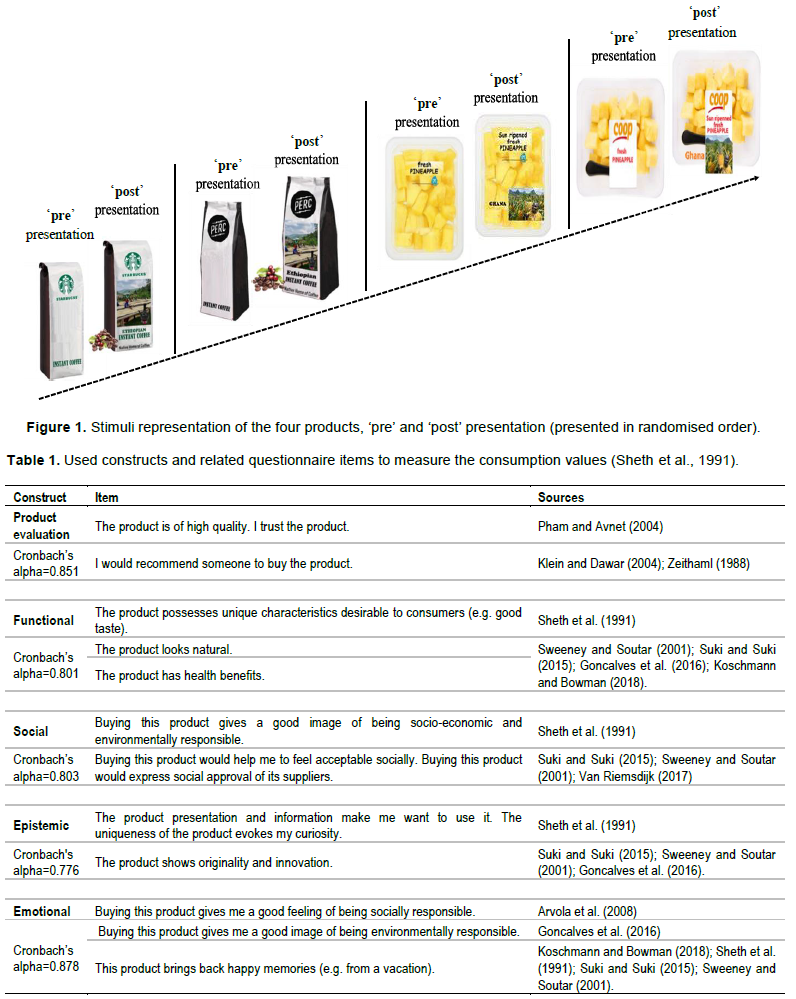

The stimuli used in Study 1 were two fast-moving consumer goods (coffee and pineapple), either with or without additional information about the African origin of the ingredient (thus, acting as a proxy for African-ingredient branding). More precisely, coffee and pineapples produced in eastern, western and southern parts of Sub-Saharan Africa were selected as target products, as they are produced primarily for the European or other export markets (CBI, 2020). The stimuli also consisted of four brands, thus making it possible to explore the robustness of effects across different brands and to increase the statistical power, in addition to increasing the number of the trials. To investigate the effect of African-ingredient branding, all of the products were first displayed to the export-market consumer without the African-ingredient brand (‘pre’; Figure 1, left), after which they were displayed with the additional African ingredient information (‘post’; Figure 1, right). This procedure is referred to as ‘pre-post’ measurement in the rest of this article.

Procedure

Data were collected through the online provider Qualtrics (https://www.qualtrics.com/). Each participating consumer assessed the same product ‘pre-post’ treatment (without and with African-ingredient branding), resulting in a within-experimental design. The online questionnaire was composed of three parts. The first part consisted of a short introduction integrating the instructions. In the second part, the stimuli were displayed, and consumers were asked to evaluate the ‘pre’ and subsequently the ‘post’ (African-ingredient branded) images of the food items along a seven-point Likert scale. Each consumer was randomly assigned to one of the four blocks. Existing and validated evaluations scales were used to measure the dependent variables. Three questions were used to assess the consumers’ general evaluation of the food products, and three items were used to represent each of the four consumption values (Sheth et al., 1991), in order to measure the consumers’ respective specific evaluations (Table 1). The items were adapted from studies by Sheth et al. (1991), by Bruner et al. (2005), and by Pham and Avnet (2004). All items displayed sufficient reliability (Cronbach’s alpha values at or above 0.7). After conducting the main tasks, the attention and involvement of the consumers were verified according to answer five control questions about the origin of the ingredients. The consumers were further asked to indicate where the commodities had been grown/produced, in addition to indicating their general level of interest in Africa. The third and final part of the online experiment consisted of a short demographic questionnaire on nationality, age, gender, education and employment status.

Participants

In all, 86 export-market consumers completed the online questionnaire. Of these respondents, 32 failed to answer at least one of the five control questions concerning the origin of the relevant African ingredient correctly, and they were excluded from the data analysis. The final sample consisted of 54 middle-aged participants (14 male). Of these participants, 33 were of Dutch nationality, 6 were of another European nationality and 8 were of non-European nationality. Given that the respondents had been recruited within a university environment, the average level of education in the sample was high, with 25 participants holding a Bachelor’s degree and 27 participants holding a Master’s degree.

Study 2

Stimuli

Study 2 is intended to explore whether the strength of a brand and/or the consumer’s attitude towards a specific African country have an effect on the consumer’s evaluation of an African-ingredient branded hedonic product. The brands are defined as either strong or weak. For the strong brand ‘The Body Shop’ was chosen, based on the fact that The Body Shop is a large chain, with approximately 2000 stores in more than 50 countries (Sinclair and Agyeman, 2005). Moreover, the wide variety of products offered by The Body Shop allows them to expand their brand equity. Based on the range of the brand, therefore, it is assumed that The Body Shop is a well-known and thus strong brand. In contrast, brands that are unfamiliar to consumers are generally defined as weak, given that consumers have no experiences that would allow them to build a brand image (Keller, 1993). For the purposes of this study, the fictitious brand ‘SkinCare’ was, therefore, created for use as a weak-brand stimulus.

In this study, Ghana and Mali were selected as the specific African countries to be used to investigate the influence of the attitudes of consumers towards specific countries of origin on their evaluations of African-ingredient branded hedonic products. Based on previous media reporting, Ghana was selected as a ‘positively’ perceived African country, which is expected to evoke more positive associations in the minds of consumers. In contrast, Mali is expected to evoke more negative associations amongst consumers, given that media recent reporting has focussed predominantly on the unstable situation in that country.

To ensure that only the influence of the host brand and the country of origin is measured, each stimulus was designed to have the same appearance. This is fundamental given the between-subject design of Study 2. The information on each hedonic product provided to the consumers was therefore exactly the same, adjusting only the independent variables-emphasising either a strong brand (‘The Body Shop’) or a weak brand (‘SkinCare’) and/or the specific African country of origin (Ghana or Mali). The African ingredient used in this study is Shea butter, a crucial ingredient in the food and cosmetic industry (Hatskevich et al., 2011). In this study, African-ingredient branding is thus operationalised as the name of the African ingredient displayed on the product’s package, along with a picture (Figure 2).

Procedure

Similar to Study 1, the first part of the experimental questionnaire consisted of instructions, asking consumers to evaluate several hedonic products. In the second part of the experiment, consumers were exposed to the stimuli and asked to evaluate the respective products along a seven-point Likert scale, utilising the same validated scales that were used in Study 1. The third and final part of the experiment consisted of a brief series of demographic and control questions. In the control questions, consumers were asked to indicate the origin of the products’ key ingredient, their perceptions of the specific African country (for each specific African country) and their general involvement with regard to Africa.

Participants

In all, 159 consumers completed the questionnaire for this experiment. Of these respondents, 43 failed to answer all of the control questions relating to the origin of the products’ key ingredients correctly. These participants were excluded from the dataset, resulting in a total sample size of 116 participants (48 male), which were used for the data analysis. The respondents ranged in age from 25 to 75 years. All participants were of Dutch nationality, and their average level of education was high (similar to Study 1). Measured as the lowest level of education completed, the respondents’ educational level ranged from ‘secondary school diploma’ to ‘post-graduate degree’.

Study 1

In order to investigate whether African-ingredient branding influenced the consumers’ evaluations across all products and goods, a mixed-factor repeated analysis of variance (ANOVA) was calculated with the within-subject factor product evaluations over time (pre and post product evaluation) and the between-subject factors brand. The results of this analysis revealed no significant interaction effects for product evaluations over time*brand (F[1,53] = 3.130, p = 0.083, ηp² = 0.057). They did reveal a significant main effect for product evaluations over time (F[1,53] = 6.355, p < 0.015, ηp² = 0.109), applying a p-value threshold of p < 0.05.

In order to explore whether the consumption values (functional, social, epistemic and emotional) influenced the relationship between African-ingredient branding and the consumers’ specific product evaluations, a mixed-factor repeated ANOVA was conducted for each consumption value separately. For all consumption values (functional, social, epistemic and emotional), the within-subject factor product evaluations over time (pre and post product evaluation for the separate product value) and the between-subject factors brand revealed no significant effects for the interaction effects product evaluations over time*brand or for product evaluations over time, applying a p-value threshold of p < 0.05. The sample indicated a high level of involvement with Africa, as indicated by a mean of M =5.58 (SD = 1.02) on a seven-point Likert scale.

Study 2

In order to investigate whether the strength of the host brand (strong vs. weak) and/or the specific African country of origin (Ghana vs. Mali) have an influence on consumers’ evaluations across all products and goods, a between-subject analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted, with the dependent variable being product evaluations, the fixed factors being strength of the host brand (strong vs. weak) and specific African country of origin (Ghana vs. Mali). The results revealed no significant interaction effect between host brand and country of origin (F[1,115] = 1.323, p = 0.253, ηp² = 0.012). They did reveal a significant main effect for the strength of the host brand (F[1.115] = 15.092, p < .000, ηp² = 0.119), but no significant main effects for specific African country of origin (F[1.115] = 1.121, p =0.292, ηp² = 0.010).

In order to estimate the effect size of the consumption values proposed by Sheth et al. (1991), a two-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANCOA) was conducted, with the four dimensions of product value (functional, social, epistemic and emotional) as the dependent variable, and with the two fixed factors host brands (strong vs. weak) and country of origin (Ghana vs. Mali). Analysis of the between-subject effects indicates that the specific African country of origin had no significant influence on any of the product-value dimensions of African-ingredient branded products. The strength of the host brand (weak vs. strong) had a significant influence on functional product value (F[2, 115] = 7.498, p = 0.007, ηp² = 0.063), with a tendency for the epistemic product value (p < 0.10), (F[2, 115] = 3.510, p = 0.064, ηp² = 0.030). Moreover, the interaction effect between host brand and African country of origin had a significant effect on the emotional dimension of product value (F[4, 115] = 10.328, p = 0.002, ηp² = 0.084).

The results indicate that consumer evaluations were more positive for the ingredients from Ghana (M=3.67) than for ingredients from Mali (M=3.05; F[2. 115] = 6.596, p = 0.012, ηp² =0.055). The export-market consumers apparently expressed a reduced general interest in/involvement with Africa, with no significant difference between the two specific African countries (F[2.115] = 2.004, p = 0.160, ηp² = 0.017).

Study 1

The results of Study 1 demonstrate that, as hypothesised in H1, African-ingredient branding can have a positive influence on evaluations of food items by export-market consumers. More precisely, the results of the general evaluations of food items in the ‘pre’ condition (in comparison to the ‘post’ condition) indicate that additional information about African ingredients significantly increases the evaluations of involved export-market consumers with regard to the ‘post’ condition, in comparison to the ‘pre’ condition.

Taking a closer look at the four consumption values (functional, social, epistemic and emotional) proposed in the theory of consumption by Sheth et al. (1991), the results indicate a tendency in which the strength of the host brand influences consumer evaluations of African-ingredient branded food items (p < 0.10). These results nevertheless failed to meet the significance threshold of p < 0.05.

The results of Study 1 add to the body of evidence, indicating that ingredient branding can enhance consumer product evaluations, whilst strengthening brand equity. African-ingredient branding follows this path, and it could therefore be seen as a valuable marketing strategy for increasing the overall profit throughout the value chain within a globalised market. Contrary to previous studies (Keller, 2003; Kotler and Pfoertsch, 2010), the results of Study 1 did not demonstrate any host-brand effect with regard to food items. This finding calls for further consideration.

Study 2

African-ingredient branding with strength of the host brand and consumer attitudes towards specific African countries

Study 2 was intended to specify the results of Study 1, which indicated that African-ingredient branding is a valuable marketing strategy. Thereby, it is intended to explore the influence of host-brand strength and consumer attitudes towards specific African countries, utilising African-ingredient branded hedonic products. The applied research approach consists of two components. First, it investigates whether the strength of the host brand has an impact on the evaluations of export-market consumers concerning African-ingredient branded hedonic products, with the host brands characterised as either strong or weak. Second, the study investigates whether consumer attitudes towards specific African countries, defined dichotomously as either negative or positive, affect their evaluations of African-ingredient branded hedonic products.

Based on the results of Study 1, which demonstrated that African-ingredient branding has a positive influence on consumers’ general evaluations of food items (consistent with H1), the overarching aim of the second study is to provide a detailed examination of whether the strength of the host brand (strong vs. weak) or attitudes towards specific African countries of origin (negative vs. positive) affect the evaluations of export-market consumers with regard to African-ingredient branded hedonic products. In comparison to Study 1, the given study focuses on a different product category (that is, hedonic products instead of food items) and is based on a sample composed purely of ‘real’ export-market consumers/shoppers.

A brand is one of a company’s most valuable intangible assets, since it operates as a powerful differentiator for businesses, manufactures, suppliers and retailers, in addition to and serving as a decision-making tool for consumers (Norris, 1992; Pinar and Trapp, 2008). Moreover, brands represent promises and build loyalty through trust, which results (at least theoretically) in continued demand and profitability (Reichheld, 2001). It should nevertheless be evident that brands themselves are differentiated according to several attributes (Carpenter et al., 1994), which could potentially affect their popularity and/or the likelihood that consumers will ‘like’ them. In turn, the likelihood that consumers will be more or less affected by a particular brand depends on the extent to which they are aware of the brand or its image. Against this background, previous studies have demonstrated that consumer perceptions of a particular host brand are of crucial influence on ingredient branding (Keller, 2003; Kotler and Pfoertsch, 2010). For this reason, whether the host brand is considered weak or strong might also have an essential effect on African-ingredient branding. Study 2 therefore investigates the influence of the strength of the host brand on African- ingredient branded products. The hypothesis in this regard (H2) is as follows:

H2: The strength of the target brand (whether it is weak or strong) has a significant influence on the evaluations of export-market consumers with regard to African-ingredient branded hedonic products.

The product perceptions of consumers also seem to be influenced by the product’s country of origin (Aichner, 2014; Al-Sulaiti and Baker, 1998; Bilkey and Nes, 1982; Kinra, 2006; Keller, 1998; Luomala, 2007; Verlegh and van Ittersum, 2001) and media (or other) reporting (Havard et al., 2019). Based on the press coverage of specific African countries, in this case, Mali and Ghana, it is therefore expected that the African country of origin and the associated media reporting have a significant influence on the evaluations of export-market consumers concerning African-branded hedonic products. Given that Mali has frequently been associated with crime, war and social/environmental disasters in media reporting, it is expected that Mali elicits negative associations in export-market consumers (in this case, Dutch consumers).

In contrast, Ghana, which is regarded as a safe place and is known for its upsurge in tourism (Owusu-Frimpong et al., 2013) is likely to elicit more positive associations in consumers. The attitudes of export-market consumers towards specific African countries of origin, whether they are perceived positively or negatively, could therefore be expected to have an influence their evaluations of African-ingredient branded products. This reasoning leads to the following hypothesis (H3):

H3: The perceptions of export-market consumers towards an African country of origin (negative or positive) have a significant influence on their evaluations of African-ingredient branded products.

Similar to Study 1, export-market consumers were asked to evaluate products in general, in addition to rating them according to specific dimensions of product value (Sheth et al., 1991), using the same validated scales that were used in Study 1. The questionnaire-based experiment was conducted using the service provider Qualtrics (https://

www.qualtrics.com/). Each consumer was randomly assigned to one of the experimental groups, resulting in a 2x2 between-subject design (2 [strong brand vs. weak brand]C 2 [country of origin {Mali vs. Ghana}]).

As indicated by the results of Study 2, the strength of the host brand has a significant effect on consumer product evaluations of African-ingredient branded hedonic products, thus supporting H2. More precisely, the results demonstrate that strong brands apparently foster positive consumer evaluations of African-ingredient branded hedonic products, as evidenced by the more positive evaluations of African-ingredient branded products associated with strong brands relative to those associated with weak brands. These findings suggest that strong brands, which are highly familiar to consumers and that are embedded within the consumer value perceptions, are particularly likely to benefit from African-ingredient branding. These results are also in line with those of previous studies demonstrating that, when an existing brand is used to introduce a new product, consumers tend to use their existing value perceptions (of the known brand or ingredient) to evaluate the new offering (Aaker and Keller, 1990; Vaidyanathan and Aggarwal, 2000). In an earlier study, Simon and Sullivan (1993) define brand equity in terms of the incremental discounted future cash flows resulting from a product associated with a brand name, in comparison to the same product without the brand name. In this vein, African- ingredient branding of strong brands might indeed generate greater financial benefits, thus acting as a valuable marketing strategy for increasing overall profits throughout the value chain.

Focusing more specifically on the value dimensions of export-market consumers (Sheth et al., 1991), the general consumer evaluations appear to be particularly driven by functional and epistemic consumption values. In this regard, the functional values, which focus on the utility derived from the perceived quality and expected performance of the product (Sheth et al., 1991; Van Riemsdijk et al., 2017), appear to be the main driver of this effect (explaining 6.3% of the variance). This finding is in line with previous research demonstrating that functional values tend to be the main factors influencing consumer choice (Gonçalves et al., 2016). Likewise, epistemic values, which refer to the capacity of a product to arouse curiosity, provide novelty or satisfy a desire for knowledge (Sheth et al., 1991); also seems to have an influence on the strength of the host brand in African-ingredient branded hedonic products. It is interesting to note that previous studies have reported similar results when using the theory of consumption values (Sheth et al., 1991) to predict consumer evaluations and, most importantly, buying behaviour with regard to green food products (Gonçalves et al., 2016; Suki and Suki, 2015).

As mentioned before, the results demonstrate that functional values are particularly decisive in the purchase of green products (Gonçalves et al., 2016), whereas functional, epistemic and social values affect the environmental concerns of consumers with regard to these products (Suki and Suki, 2015). These results clearly suggest that the consumers’ consumption-value evaluations of African-ingredient branded products and their associated brand strength support the promising idea of combining African-ingredient branding with strong brands, whilst enhancing brand equity by focusing on the functional values of the African ingredient. African farmer organisations and policy-makers might therefore do well to focus more on the functional attributes that are associated with Africa, building on the specific biological and environmental conditions. This finding is consistent with the observations of Ingenbleek (2019; 2020), who argues that the most important comparative advantages of African countries are rooted in their biogeographic environments.

In response, Papadopoulos and Hamzaoui-Essoussi (2015) called for investigation of the interaction between consumer image of the African continent and those of specific African countries and regions. The results of Study 2 suggest that consumers’ attitudes towards specific African countries have no significant effect on their evaluations of African-ingredient branded products. This is in line with recent research demonstrating that the African continent is poorly understood (Matiza and Oni, 2013), consumer perceptions of Africa might therefore metaphorically be described as an ‘amorphous grey mass of poverty … corruption … pestilence … and several other inauspicious features’ (Osei and Gbadamosi, 2011; Papadopoulos and Hamzaoui-Essoussi, 2015). Against this background, and given the hierarchical structure of the consumers’ mental schemes, consumers (especially those who are uninformed or have a reduced involvement) might have a more general image of specific African countries, thereby interpreting the African-branded hedonic products at a more general ‘continental level’. This effect is known as the ‘continent effect’ (Papadopoulos and Hamzaoui-Essoussi, 2015; Wanjiru, 2006), and it involves ignoring country-specific associations related to particular African country.

The continent effect (Wanjiru, 2006) is supported by the results of the current study with regard to the two control variables, which were presented to the participants at the end of the experiment to examine the consumers’ general involvement with regard to the African continent and their specific perceptions of the countries (Mali and Ghana). The results revealed significant differences in the consumers’ specific perceptions of the two countries (when asked directly), as evidenced by the more positive evaluations expressed for Ghana, in comparison to their evaluations for Mali. However, at the same time, the consumers apparently expressed less general interest in, and therefore involvement with regard to, Africa, and no differences were observed between the two specific African countries.

Based on these results, it would be reasonable to conclude that, although consumers perceive specific African countries as more positive or more negative in comparison to other specific African countries (when asked directly), these perceptions do not affect their evaluations of African-ingredient branded products. The tendency to perceive specific African countries as positive or negative might therefore not act as a catalyst for an advanced cognitive thinking process, which is instead based on an initial ‘continental’ impression of Africa (Wanjiru, 2006). Against this background, it might be concluded that export-market consumers are not very interested in specific African countries, instead considering Africa as a single coherent entity, ignoring the diversity of African countries and the environmental conditions associated with them.

Implications

Several studies have investigated ingredient branding in general (Rodrigue and Biswas, 2004; Tepic et al., 2014), demonstrating that, in theory, African-ingredient branding might be a valuable marketing strategy (Papadopoulos and Hamzaoui-Essoussi, 2015, Sigué, 2012). To date, however, there have been no empirical examinations of ingredient branding within the context of commodities grown/produced in Africa. The concept of African-ingredient branding nevertheless seems to be a promising marketing strategy for increasing return on investment for several stakeholders, as well as for integrating farmers and intermediaries from frontier markets. This strategy involves depicting positive product attributes and specific images of the host product, based on the natural and heritage features of African commodities (Verlegh and van Ittersum, 2001; Sigué, 2012; Papadopoulos and Hamzaoui-Essoussi, 2015). Against this background, the current empirical investigation of the evaluations of export-market consumers with regard to African-ingredient branded products provides initial experimental insight into how consumer perceptions of food items and hedonic products might be influenced by additional information about ingredients grown/produced in Africa, as well as by the strength of host brands and the consumer attitudes towards specific African countries.

The results of Study 1 support the idea of applying African-ingredient branding as a valuable marketing strategy for increasing brand equity. Moreover, as indicated by the results of Study 2, the strength of the host brand has a significant influence on consumer product evaluations. At the same time, however, the attitudes that export-market consumers have towards specific African countries of origin do not have any significant influence on their evaluations of African-ingredient branded products, whether in general or at the level of consumption values (Sheth et al., 1991).

The current research makes a theoretical contribution to the existing body of research on ingredient branding by examining ingredient branding within the context of agricultural commodities grown/produced in Africa. Through its experimental assessment, this study also contributes to the marketing and branding literature by providing an experimental framework for measuring the effect of African-ingredient branding with regard to agricultural commodities. The marketing strategy of African-ingredient branding was formulated, operationalised and validated to depict product attributes and a specific image of the product’s place of origin. These aspects determine the functional attributes of a product (quality and taste), in addition to highlighting its epistemic values. The experimental investigation of the evaluations of export-market consumers therefore provides initial insight into how branded food items and hedonic products from Africa influence export-market consumer evaluations.

From a managerial point of view, the results indicate that African-ingredient branding has the potential to increase revenue, profit and return on investment for intermediaries, manufacturers, producers and farmers, including those in frontier-country markets. More precisely, the results provide the following practical-normative implications: First, most importantly, the results suggest that African-ingredient branding could be a useful and valuable marketing strategy for building brand equity, whilst having a positive influence on the evaluation processes of export-market consumers with regard to food items. Given that functional and epistemic consumption values seem to be particularly likely to drive the effects of the strength of the host brand displayed, efficient and effective product presentations should evoke curiosity in consumers, in addition to enhancing the utility derived from perceived quality and consumer (emotional) attachment to the product. In this vein, African farmers might do well to concentrate on the functional attributes of African-grown commodities in their marketing strategies, in addition to cooperating with brand/market leaders. Second, given that specific African countries of origin apparently have no effect on the evaluations of export-market consumers, and in line with existing evidence of a ‘continent effect’ (Wanjiru, 2006), marketers seeking to apply African-ingredient branding might benefit from focusing more on Africa as a coherent continental entity. It should nevertheless be evident that further research is needed in order to examine whether overall perceptions of Africa as a continent might be more likely to affect consumer perceptions than are perceptions of specific African countries, even in light of current media reporting with reference to Africa. Third, farmers and producers might benefit from the insights into what consumers in developed markets are interested in, which could help them to adapt their production to the needs of export-market consumers, thereby improving their ability to serve these markets. Fourth, the knowledge that African-ingredient branding add value to products and/or goods can be used to develop innovative product or service concepts that could enhance differentiation on a dynamic market or that could increase the value of commodities that are grown/produced in Africa and, by extension, African agricultural products.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

The limitations of this study suggest several avenues for future research. The current studies were limited to the use of food items and hedonic products. Extending the research scope to include other product categories might therefore provide a better representation of African-ingredient branding, thereby leading to innovative research findings. In addition, the research findings concerning the hypotheses about African ingredients might be limited, as they were examined using only two countries of origin. Further research based on several African countries or the integration of Africa as a ‘continent (effect)’ might therefore be able to provide advanced evidence of the patterns of African-ingredient branding observed in this study. The measurement items in the current research work were derived largely from the consumption values proposed by Sheth et al. (1991). Future studies could address a broader array of consumption values in addition, to incorporating other theoretical constructs in order to measure the ‘perceived values of consumers’ (Sweeney and Soutar, 2001). Future studies could also address behavioural intention variables, like the willingness to pay or the willingness to accept, in order to investigate the naturalistic, marketing-relevant effects of African-ingredient branding. Such studies could also implement additional control variables (such as age, income, cognitive capacity, product knowledge), possibly reinforcing the current research results.

This research work contributes to the large body of literature focusing on ingredient branding. The result of the first study demonstrate that African-ingredient branding, utilising commodities grown/produced in Africa, has a positive influence on the evaluations of export-market consumers with regard to specific food items. The results of the second study suggest that the strength of the host brand is particularly likely to influence the evaluations of export-market consumers with regard to hedonic products. In terms of the theory of consumption values (Sheth et al., 1991), the results of this study further suggest that functional values and, to a lesser extent, epistemic values affect the evaluations of consumers; thus potentially influencing their behaviour as well. The findings reported here have theoretic and practical implications for researchers, marketing practitioners, intermediates and farmers, suggesting that African-ingredient branding could be used as a valuable marketing strategy for increasing overall profits throughout the value chain.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Aaker DA, Keller KL (1990). Consumer evaluations of brand extensions. Journal of Marketing 54(1):27-41.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Aichner T (2014). Country-of-origin marketing: A list of typical strategies with examples. Journal of Brand Management 21(1):81-93.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Al-Sulaiti KI, Baker MJ (1998). Country of origin effects: A literature review. Marketing Intelligence and Planning 16(3):150-199.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Arvola A, Vassallo M Dean M, Lampila P, Saba A, Lähteenmäki L, Shepherd R (2008). Predicting intentions to purchase organic food: The role of affective and moral attitudes in the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Appetite 50(2-3):443-454.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Beverland M, Lindgreen A (2002). Using country of origin in strategy: The importance of context and strategic action. Journal of Brand Management 10(2):147-167.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bilkey WJ, Nes E (1982). Country-of-origin effects on product evaluations. Journal of International Business Studies 13(1):89-100.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bruner GC, Hensel PJ, James KE (2005). Marketing scales handbook. Chicago, IL: American Marketing Association. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Carpenter GS, Glazer R, Nakamoto K (1994). Meaningful brands from meaningless differentiation: The dependence on irrelevant attributes. Journal of Marketing Research 31(3):339-350.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

CBI - Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2020). Exporting fresh fruit and vegetables to Europe. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Czellar S (2003). Consumer attitude toward brand extensions: An integrative model and research propositions. International Journal of Research in Marketing 20(1):97-115.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dadzie KQ, Sheth JN (2020). Perspectives on Macromarketing in the African Context: Introduction to the Special Issue.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dalman MD, Puranam K (2017). Consumer evaluation of ingredient branding strategy. Management Research Review 40(7):768-782.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Desai KK, Keller KL (2002). The effects of ingredient branding strategies on host brand extendibility. Journal of Marketing 66(1):73-93.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Faquhar PH (1989). Managing brand equity. Marketing Research 1(3):24-33.

|

|

|

|

|

Gallarza MG, Gil-Saura I, Holbrook MB (2011). The value of value: Further excursions on the meaning and role of customer value. Journal of Consumer Behavior 10(4):179-191.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ghodeswar BM (2008). Building brand identity in competitive markets: A conceptual model. Journal of Product and Brand Management 17(1):4-12.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Goldblatt P (1997). Floristic diversity in the Cape flora of South Africa. Biodiversity and Conservation 6(3):359-377.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gonçalves HM, Lourenço TF, Silva GM (2016). Green buying behavior and the theory of consumption values: A fuzzy-set approach. Journal of Business Research 69(4):1484-1491.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gore-Langton L (2016). Consumers willing to pay 75 per cent more for known ingredients: survey. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Hatskevich A, Jenicek V, Darkwah SA (2011). Shea industry-A means of poverty reduction in Northern Ghana. Agricultura Tropica et Subtropica 44(4):223-228.

|

|

|

|

|

Havard CT, Ferrucci P, Ryan TD (2019). Does messaging matter? Investigating the influence of media headlines on perceptions and attitudes of the in-group and out-group. Journal of Marketing Communications 2019:1-11.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Herz M, Diamantopoulos A (2017). I use it but will tell you that I don't: Consumers' country-of-origin cue usage denial. Journal of International Marketing 25(2):52-71.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Holbrook MB (1999). Consumer value: A framework for analysis and research. Psychology Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Hsu CL, Chang CY, Yansritakul C (2017). Exploring purchase intention of green skincare products using the theory of planned behavior: Testing the moderating effects of country of origin and price sensitivity. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 34:145-152.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ietto-Gillies G (2019). The role of transnational corporations in the globalisation process. In The Handbook of Globalisation, Third Edition. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ingenbleek PT (2019). The Endogenous African Business: Why and How It Is Different, Why It Is Emerging Now and Why It Matters. Journal of African Business 20(2):195-205.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ingenbleek PT (2020). The Biogeographical Foundations of African Marketing Systems. Journal of Macromarketing 40(1):73-87.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jongmans E, Dampérat M, Jeannot F, Lei P, Jolibert A (2019). What is the added value of an organic label? Proposition of a model of transfer from the perspective of ingredient branding. Journal of Marketing Management 35(3-4):338-363.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kanama D, Nakazawa N (2017). The effects of ingredient branding in the food industry: Case studies on successful ingredient-branded foods in Japan. Journal of Ethnic Foods 4(2):126-131.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kathuria LM, Gill P (2013). Purchase of branded commodity food products: Empirical evidence from India. British Food Journal 115(9):1255-1280.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Keller KL (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing 57(1):1-22.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Keller KL (1998). Brand knowledge structures. Strategic brand management: Building, measuring, and managing brand equity. pp. 86-129.

|

|

|

|

|

Keller KL (2003). Brand synthesis: The multidimensionality of brand knowledge. Journal of Consumer Research 29(4):595-600.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Keller KL, Brexendorf TO (2019). Measuring brand equity. In Handbuch Markenführung. Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden. pp. 1409-1439.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kinra N (2006). The effect of country-of-origin on foreign brand names in the Indian market. Marketing Intelligence and Planning 24(1):15-30.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Klein J, Dawar N (2004). Corporate social responsibility and consumers' attributions and brand evaluations in a product-harm crisis. International Journal of Research in Marketing 21(3):203-217.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Koschmann A, Bowman D (2018). Evaluating marketplace synergies of ingredient brand alliances. International Journal of Research in Marketing 35(4):575-590.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kotler P, Keller KL (2016). Marketing Management. Global Edition (Vol. 15E). Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Kotler P, Pfoertsch W (2010). Ingredient branding: making the invisible visible. Springer Science & Business Media.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lee WJ, O'Cass A, Sok P (2017). Unpacking brand management superiority: Examining the interplay of brand management capability, brand orientation and formalisation. European Journal of Marketing 51(1):177-199.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Leuthesser L, Kohli C, Suri R (2003). 2+ 2= 5? A framework for using co-branding to leverage a brand. Journal of Brand Management 11(1):35-47.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Long MM, Schiffman LG (2000). Consumption values and relationships: Segmenting the market for frequency programs. Journal of Consumer Marketing 17(3):214-232.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lorenz BA, Hartmann M, Simons J (2015). Impacts from region-of-origin labeling on consumer product perception and purchasing intention-Causal relationships in a TPB based model. Food Quality and Preference 45:149-157.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Luomala HT (2007). Exploring the role of food origin as a source of meanings for consumers and as a determinant of consumers' actual food choices. Journal of Business Research 60(2):122-129.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Matiza T, Oni OA (2013). Nation branding as a strategic marketing approach to foreign direct investment promotion: The case of Zimbabwe. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 4(13):475.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Moon H, Sprott DE (2016). Ingredient branding for a luxury brand: The role of brand and product fit. Journal of Business Research 69(12):5768-5774.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Norris DG (1992). Ingredient branding: A strategy option with multiple beneficiaries.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Oberecker EM, Diamantopoulos A (2011). Consumers' emotional bonds with foreign countries: does consumer affinity affect behavioral intentions?. Journal of International Marketing 19(2):45-72.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Osei C, Gbadamosi A (2011). Re-branding Africa. Marketing Intelligence and Planning 29(3):284-304.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Owusu-Frimpong N, Nwankwo S, Blankson C, Tarnanidis T (2013). The effect of service quality and satisfaction on destination attractiveness of sub-Saharan African countries: The case of Ghana. Current Issues in Tourism 16(7-8):627-646.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Papadopoulos N, Hamzaoui-Essoussi L (2015). Place images and nation branding in the African context: Challenges, opportunities, and questions for policy and research. Africa Journal of Management 1(1):54-77.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Pham MT, Avnet T (2004). Ideals and oughts and the reliance on affect versus substance in persuasion. Journal of Consumer Research 30(4):503-518.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Pinar M, Trapp PS (2008). Creating competitive advantage through ingredient branding and brand ecosystem: the case of Turkish cotton and textiles. Journal of International Food and Agribusiness Marketing 20(1):29-56.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ponnam A, Balaji MS, Dawra J (2015b). Fostering a motivational perspective of customer-based brand equity. The Marketing Review 15(1):3-16.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ponnam A, Sreejesh S, Balaji MS (2015a). Investigating the effects of product innovation and ingredient branding strategies on brand equity of food products. British Food Journal 117(2):523-537.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Radighieri JP, Mariadoss BJ, Grégoire Y, Johnson JL (2014). Ingredient branding and feedback effects: The impact of product outcomes, initial parent brand strength asymmetry, and parent brand role. Marketing Letters 25(2):123-138.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Reichheld FF (2001). Lead for loyalty. Harvard Business Review 79(7):76-84.

|

|

|

|

|

Rodrigue CS, Biswas A (2004). Brand alliance dependency and exclusivity: An empirical investigation. Journal of Product and Brand Management 13(7):477-487.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sheth JN, Newman BI, Gross BL (1991). Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. Journal of Business Research 22(2):159-170.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sigué SP (2012). Adding value to African commodities: Could ingredient branding be a solution?. Journal of African Business 13(1):1-4.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Simon CJ, Sullivan MW (1993). The measurement and determinants of brand equity: A financial approach. Marketing Science 12(1):28-52.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sinclair A, Agyeman B (2005). Building global leadership at The Body Shop. Human Resource Management International Digest 13(4):5-8.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Suki NM, Suki NM (2015). Impact of consumption values on consumer environmental concern regarding green products: Comparing light, average, and heavy users'. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 5(1):82-97.

|

|

|

|

|

Sweeney JC, Soutar GN (2001). Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. Journal of Retailing 77(2):203-220.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Tepic M, Fortuin F, Kemp R, Omta O. (2014). Innovation capabilities in food and beverages and technology-based innovation projects. British Food Journal 116(2):228-250.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Vaidyanathan R, Aggarwal P (2000). Strategic brand alliances: implications of ingredient branding for national and private label brands. Journal of Product and Brand Management 9(4):214-228.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Van Ittersum K (2001). The role of region of origin in consumer decision-making and choice. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Van Ittersum K, Candel MJ, Meulenberg MT (2003). The influence of the image of a product's region of origin on product evaluation. Journal of Business Research 56(3):215- 226.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Van Riemsdijk L, Ingenbleek PT, Houthuijs M, van Trijp HC (2017). Strategies for positioning animal welfare as personally relevant. British Food Journal 119(9):2062-2075.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Verlegh PW, Steenkamp JBE, Meulenberg MT (2005). Country-of-origin effects in consumer processing of advertising claims. International Journal of Research in Marketing 22(2):127-139.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Verlegh PW, van Ittersum K (2001). The origin of the spices: The impact of geographic product origin on consumer decision making. Food, People and Society. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 267-279.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Wanjiru E (2006). Branding African countries: A prospect for the future. Place Branding 2(1):84-95.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Webster FE, Keller KL (2004). A roadmap for branding in industrial markets. Journal of Brand Management 11(5):388-402.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Winit W, Gregory G, Cleveland M, Verlegh P (2014). Global vs local brands: How home country bias and price differences impact brand evaluations. International Marketing Review 31(2):102-128.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Zeithaml VA (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing 52(3):2-22.

Crossref

|

|