Guanxi orientation is one of the important organizational values in China. This study examines the effect of guanxi orientation on firm’s boundary spanner’s behavior (manifested by interpersonal liking and interaction frequency) and its influence on inter-firm relationships in Chinese marketing channel context. Drawing on organizational culture and boundary spanner theory, a conceptual model is proposed to delineate how guanxi orientation works across organizations where inter-firm support is placed as the key mediator. Results from 342 distributors show that guanxi orientation has positive influence on interpersonal liking and interaction frequency between boundary spanners, and the manifested behaviors have direct and indirect impact on inter-firm relationship quality through inter-firm support. Overall, the study research extended the extant literature from three perspectives. Firstly, this study deepens our understanding of the organizational role of guanxi orientation and its influence on boundary spanner’s individual behaviors, building a bridge between intra- and inter-firm relationships. Secondly, the research findings suggest that boundary spanners can provide inter-firm support for building cooperative relationship channels. Thirdly, inter-firm support is found to be another antecedent of long-term orientation (previously trust, dependence, and performance), which provides a cost-effective way for building deeper relationship. Contributions, managerial implications, limitations, and future research are also pointed out.

First, we will explain definitions of organizational values, guanxi, guanxi orientation, and boundary spanners, and then discuss the overall influence of organizational values on channel relationship management.

Organizational values

Values are defined as “a conception, explicit or implicit…of the desirable which influences the selection form available modes, means, and ends of action” (Scott, 1965). Connor and Becker (1975) gave a brief definition of values, “global belief about desirable end-states underlying attitudinal and behavioral processes”.

As a result, behavior generally is viewed as a manifestation of values and attitudes (Connor and Becker, 1975). Then, values can predict organizational performance (considered as organizational behavioral outcomes) and individuals’ behaviors.

Specifically, organizational values, reflecting what is important to the members in the organization, once established and institutionalized, can have a significant impact on the values and behaviors of individual employees and organizational performance (Brown, 1976; Badovick and Beatty, 1987).

Badovick and Beatty (1987) have found that shared organizational values transmitted to employees’ impact marketing strategies and practices at various levels of organizations help motivate their behaviors, which further influence their ultimate business performance and relationship with partners (Jackson and Tax, 1995).

Schwartz and Davis (1981) indicated that for greater level of shared organizational values, higher likelihood of characteristic behavior leads to successful organizational performance. Early researchers in organization and marketing have also investigated the effect of organizational values on employees’ ethical behaviors (Somers, 2001), job satisfaction (Lund, 2003), marketing strategy implementation and planning (Badovick and Beatty, 1987), individual selling performance (Flaherty et al., 1999) and marketing professionals’ organizational commitment (Hunt et al.,1989).

Guanxi and guanxi orientation

Guanxi

Before introducing guanxi orientation, it is necessary to give a full understanding of the concept of guanxi. As a relational society, Chinese people are embedded in various kinds of social relations (guanxi), and guanxi has been regarded as a key principal to do business in China. Guanxi generally refers to relationships or social connections based on mutual interests and benefits (Wang, 2007).

Literally, the Chinese character “guan” means a gate, and “xi” means relationship, tie or connection. Therefore, guanxi means “pass the gate and get connected” (Lee and Dawes, 2005). Guanxi represents interpersonal connections embedded with reciprocal favors, trust, mutual obligations and assistances. Previous research measure guanxi from three dimensions: ganqing (emotional attachment), xinren (trust), and renqing (reciprocity or favor).

Ganqing, meaning emotional attachment, is defined as the degree of mutual personal friendship, indicating closeness among members of a social network. Among various kinds of guanxi, emotional attachment with families or relatives is the strongest (Hwang, 1987).

Xinyong, has similar meaning with trust, which indicates the confidence or belief that the exchange partner has on the credibility and benevolence (Chen and Chen, 2004). Renqing implies that once a benefactor gives a benefit to another, the receiver is obligated to repay the favor in order to restore balance (Hwang, 1987).

Guanxi is rooted in a culture characterized by interdependence and reciprocity. Through constant exchange of favor in the form of gift-giving and bouquet inviting, renqing is practiced between individuals, and extensive interpersonal networks to share scarce resources and cope with uncertainties are developed. Renqing follows the rule of reciprocity strictly (Barnes et al., 2011).

Aforementioned are key concepts involved with guanxi. In addition, saving face (mianzi) is also important in daily interactions. Previous research on guanxi are mostly from individual-level perspective (Chen et al., 2011; Luo, 2001; 2007), based on personal relationships. Individuals build guanxi through interpersonal favor seeking, mutual help, obligation fulfilling, and so on.

Although facets of guanxi in relation to individuals have been explored, limited research has been undertaken from organizational perspective and with regard to its organizational influence. Specifically, Su et al. (2003) defined guanxi as a coalition of resources which business parties share to enhance performance from a business perspective.

In buyer-supplier relationship, guanxi is defined as “a special type of personal particular ties that bonds the boundary spanners of exchange partners through social activities, reciprocal obligations and favor exchanges” (Chen et al., 2011; Peng and Luo, 2000).

Since an organization is a social unit of people with the same collective goals, organizational-level guanxi is believed to be an aggregate of interpersonal guanxi between organizations or as cross-organizational connections among managers (Chen et al., 2011; Park and Luo, 2001; Murray and Fu, 2016).

Moreover, through empirical in-depth interviews, Murray and Fu (2016) indicate that if the employee utilizes guanxi for firm’s benefits and guanxi partners are aware of the employee’s intentions and engage in reciprocal behaviors for the sake of the employee’s organization, individual-level guanxi can be transformed into the organizational-level asset.

Guanxi orientation

Compared to Guanxi, Guanxi orientation is more concerned with firms’ strategic goals. The strategic orientations of firms represent the elements of the firm’s culture that guide interactions in the marketplace and impact managerial decision making (Noble et al., 2002). Guided by guanxi orientation, the extent to which boundary spanners use interpersonal guanxi is determined by their firms’ strategic needs and their cultural norms simultaneously (Luo, 2001; Su et al., 2009).

Murray and Fu (2016) pointed out that, as business exchanges are embedded in social relationships and guanxi permeates throughout the Chinese society all-round, examining how firms employ guanxi as a strategic orientation is of high significance. They emphasize that strategic guanxi orientation stands for a business philosophy of guanxi management, reflecting “an organization-wide culture that focuses on embedded values and beliefs that guide behaviors that ultimately influence performance” (Murray and Fu, 2016).

Extant research treats guanxi orientation as an individual-level construct, defined as “the extent to which people willingly recognize obligations, harmony, and long-term reciprocation in their daily socialization” (Murray and Fu, 2016; Su et al., 2009). Among the most research, a large part focus on the utilizations stage of guanxi orientation, and found that guanxi utilization has significant influence on sales growth, employee’s unethical behavior, conflict, communication, channel relationship quality, and power use (Park and Luo, 2001; Su et al., 2003; Zhang and Zhang, 2006; Cai et al., 2016; Muarry and Fu, 2016).

In organizational level, Su et al. (2003) do not give an explicit understanding of guanxi orientation but emphasize the importance and benefits of using guanxi in business exchanges. Firms need organizational-level principles and guidelines for employees to follow and to resolve daily problems and cope with challenges created by constant environmental changes (Murray and Fu, 2016).

Similar to market orientation, which is defined as “the organizational culture that most effectively and efficiently creates the necessary behaviors for the creation of super value for buyers and thus superior performance for the business” (Narver and Slater, 1990), in this study, guanxi orientation is a kind of organizational culture typical in Chinese context, encouraging boundary-spanning employees to actively establish and build interpersonal relationship with their counterparts of partner firms. Institutionalized as a kind of organizational culture, guanxi orientation of firms fosters a kind of organizational environment and creates policies that are conductive for boundary spanners to acquiring interpersonal guanxi.

Boundary spanners are individuals most closely involved in inter-firm relationships and take the responsibility of shaping inter-firm relationships. Considering boundary spanners’ inter-organizational role, investigating intra- and inter-firm influence of guanxi orientation on employees and cooperating partners from the organizational culture perspective is of strategic significance.

Guanxi orientation and boundary spanner’s behavior

Research on organizations have found that organizational values have significant influence on the overall business environment, employees’ behaviors and attitudes (Brown, 1976; Badovick and Beatty, 1987), such as performance, job satisfaction (Somers, 2001; Lund, 2003), as aforementioned. It is reasonable to believe that guanxi orientation as one of the most important organizational values in China, influence behaviors of employees, especially boundary spanners from both parties. Before discussing the relationship between guanxi orientation and behaviors of boundary spanners, we give a brief introduction to the role of boundary spanners in inter-firm exchange.

Boundary spanners are special employees that are more closely involved in inter-organizational relationships than any other in their organizations in inter-firm exchange of marketing channels. They are aware of firm information on inter-organizational relationships, act on behalf of their organizations, come in direct contact with their counterparts, support inter-firm information exchange, facilitate organizational responses to external environment, play a dual role in inter-firm exchange, are involved in business decisions and operations and have an important influence in shaping inter-firm exchange (Zaheer et al., 1998; Lee and Dawes, 2005).

Huang et al. (2016) pointed out two main roles of boundary-spanners: information processing and external representation. Boundary spanners’ behaviors are also deeply shaped and modified under the organizational values of guanxi orientation. Based on this study research context, boundary spanners here refer to salespersons from manufacturers and purchasing managers from distributors.

Guanxi orientation here is defined as organizational-level construct, working as organizational values and guiding boundary spanners’ behaviors, which guides employees on how to build guanxi with counterparts, and reflects connections among firms seeking resources and support to achieve common organizational goals.

Guanxi-oriented firms treat partners as business friends and believe that they will make it through together, although each firm is interests-oriented. Normally, firms use contracts as one of the govern mechanisms to regulate exchanges with partners. The contracts include almost every aspect of activities during their cooperation with their parties.

However, the contracts are not perfect and sometimes when urgent or unpredictable things happen, firms have to come up with appropriate solutions. In this case, firms with guanxi orientation will seek help from their guanxi networks to work out a plan.

In case of limited resources, guanxi can also become a rescue strategy or a survival practice offering an extra protective mechanism (Barnes et al., 2011; Xin and Pearce, 1996). However, all the operating details have to be implemented by boundary spanners. Boundary employees will take on firms’ values gradually and practice them in their work.

For example, during the process of building interpersonal guanxi with counterparts, boundary spanners meet with each other face to face or on the phone to discuss details of two sides frequently (ordering, pricing, promotion, time, etc.), whenever on working hours or not, wherever in the office or any other places. Most importantly, the time, money or any other kind of resources invested in the firm- and individual-level relationships cannot be transported to other relationships easily, since it is one kind of relationship-specific investment.

Cai et al. (2016) mentioned that ties between boundary spanners may be initiated by their firm’s strategic decisions on the selection of trading partners. Guanxi orientation, as one of the most important strategic orientations, guides boundary spanners through encouraging building interpersonal relationship and trust with counterparts, which is a precondition for nurturing a favorable inter-firm relationship. During this process, favor is given in reciprocal way, such as critical information or resources (money, infrastructure, etc.).

Boundary spanners follow the guidelines of guanxi orientation step by step. They are motivated to actively engage in and spend time on building guanxi with counterparts, such as through gifting-giving, regular visits, favor exchanging, hosting and attending banquets, preferential treatment, and so on. As a result, interpersonal relationship between boundary spanners is improved and they interact in a more frequent base.

Interpersonal liking and interaction frequency is used as manifestations of guanxi building behaviors, to measure ganqing, strength of personal relationships between boundary spanners of manufacturers and distributors. Interpersonal liking refers to the affective attachment or positive affect, indicating closeness between boundary spanners. Barnes et al. (2011) mentioned that ganqing dimension of guanxi reflects liking shared by the buyer and seller.

Nicholson et al. (2001) define this construct as “an emotional connection that one feels for another that can be viewed as fondness or affection — a feeling that goes beyond the mere acceptance of a competent business partner”. Even if the inter-organizational relationship were to terminate, personal contact with strong interpersonal liking would remain.

Nicholson et al. (2001), Hawke and Heffernan (2006), Abosag and Lee (2013), and Abosag and Naude (2014) have found the important role of interpersonal liking in shaping buyer-seller trust. Nicholson et al. (2001) also found that as the bilateral relationship ages, liking plays a more important role in building trust. Research of Abosag et al. (2013; 2014) on interpersonal liking were mainly done in Saudi Arabia, where local business culture is similar to guanxi in China.

In addition, the strength of interpersonal liking is related to the amount of time boundary spanners invest and spend together (Huang et al., 2016; Granovetter, 1985). More regular visits or social gatherings, more frequently they meet. With an increase in interaction frequency, boundary spanners spend more time together, and they exchange information and predict each other’s behaviors more easily (Doney and Cannon, 1997).

Frequent interactions also increase opportunities for both manufacturer and distributor to gather personal information and empathize with others’ perspective. As the time when boundary spanners work together becomes longer, face to face meetings or phone contacts are more frequent and individual relationships are becoming closer. Following this reasoning, interpersonal liking or emotional attachment is deeper. It has to be mentioned that as guanxi orientation advocates mutual obligations, assurances, and understanding in daily interactions, boundary spanners are believed to repay the favors, fulfill their duties and offer timely help to counterparts.

A proactive favor to counterparts creates expectations for future help. If the counterpart does not repay the favor or provide help, he or she will lose credibility in the cooperation relationship and will not receive help from partners in time of emergency. Therefore, we propose that:

Hypothesis 1a: Guanxi orientation is positively related to interpersonal liking between boundary spanners.

Hypothesis 1b: Guanxi orientation is positively related to frequency of interactions between boundary spanners

Hypothesis 1c: The more frequently boundary spanners interact, the more deeply the interpersonal liking is fostered.

Boundary spanner and relationship quality

Firm’s guanxi orientation values create an atmosphere which motivates boundary spanners to interact or contact with each other on a frequent basis to develop interpersonal liking, thereby facilitating firm-level reciprocal support and building cooperative relationship.

Boundary spanners building guanxi not only enriches their personal own network, but also contributes to their firms’ achievement. When the boundary spanners have fostered personal network and has been emotionally tied to each other (high-level interpersonal liking), it leads to interpersonal favors as well as inter-firm support (Cai et al., 2016).

Based on the emotional attachment between boundary spanners, smoother operational process and decreased associated transaction cost by facilitating the transformation of interpersonal into inter-firm connections are achieved. We use the term “support” to refer to the assistance or help offered by one firm to its partner, including informational and physical help (Langenberg, 2007).

In the bilateral relationship, critical information and urgent physical assistance are frequently transferred especially in cooperative inter-firm exchange. In channel management, information support includes consumer preferences, best selling price or place, and promotion plan, etc. Physical support consists of money, labor and key physical resources, etc.

The provision of critical valuable information depends on interpersonal liking or closeness between boundary spanners (Luo, 2007). Strong interpersonal liking serves as a robust base for connecting and sharing information with other boundary spanners (Huang et al., 2016). If they are in close relationship, the boundary spanners will try to persuade his/her counterpart to offer the valuable information, or his/her counterpart will provide the information voluntarily. Even if the information is difficult to collect, the counterpart is willing to facilitate the internal data collection process and make it possible to transmit the requested information to its partner (Cai et al., 2016).

Similarly, physical support will also be provided to the boundary spanner by his/her counterpart when necessary. Moreover, the boundary spanner will also influence other members in his/her firm to share the same cooperative attitude to the counterpart’s firm and to provide necessary help. Specially in China, some of the managers of distributors are not only boundary spanners but also owners of the distribution firm, who are in charge of the whole firm and make decision on whether or not to offer help.

As a result, closer relationship, more frequent contacts between boundary spanners create appropriate conditions for inter-firm exchange and offering inter-firm support to cooperative partner. As this study was conducted from distributor’s side, we propose that the closer the personal relationship between boundary spanners, more support will distributors provide to the inter-firm exchange, and advance the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2a: Interpersonal liking is positively related to inter-firm support.

Hypothesis 2b: Interaction frequency is positively related to inter-firm support.

Further, inter-firm support contributes to relationship quality between manufacturers and distributors. We use conflict and long-term orientation to measure relationship quality in this study, demonstrating positive and negative aspects of the inter-firm relationship in marketing channels.

Long-term orientation is considered to be “expectations of continuity of a relationship” between firms (Noordewier et al., 1990), emphasizing the likelihood of future interactions and desire of both parties towards a long-term relationship (Lee and Dawes, 2005). Maintaining a long-term buyer-seller relationships are considered as the core of marketing activities (Ryu et al., 2007).

A couple of factors influence long-term orientation between channel partners, such as trust (interpersonal or inter-firm), dependence and performance (Cannon et al., 2010; Ganesan, 1994; Lee and Dawes, 2005). Meanwhile, conflict between two parties is defined as the behaviors or feelings of interdependent parties in response to potential or actual obstructions that impede one or more of the parties achieving their goals (Gaski and Nevin, 1985).

This is manifested by perceived disagreements between channel members with respect to important issues of mutual concern (Brown and Day, 1981). Rosenberg and Stern (1971) stated that conflict in distribution channels is inherent, pervasive and potentially disruptive. It is vital to find antecedents and resolutions to solve negative conflicts between two parties.

Combined with this study research, the manufacturer and distributor provide informational or physical support to each other, they take partners’ needs into consideration and offer timely help proactively. Information communication enables both parties to know each other’s plans, strategies, and operation details, serving trading partners better. It also helps partners prepare themselves to coordinate their business exchanges timely.

Physical support can help partners resolve urgent problems, such as resources, or promotional marketing programs. On this basis, business support would not only stifle the signs of conflict between manufacturer and distributor in cradle but also enables them to be more confident to cooperate effectively and build solid foundation for long-term orientation. In sum, we propose that:

Hypothesis 3a: Inter-firm support is negatively related to inter-organizational conflict.

Hypothesis 3b: Inter-firm support is positively related to inter-organizational long-term orientation.

This study emphasizes the significance of guanxi orientation as organizational values in intra- and inter-firm relationship management. Boundary spanners serve as bridge connecting the manufacturers and distributors, who make contacts with trading partners and perform operational activities. Influenced by firm’s guanxi orientation values, they adjust their behaviors and commit themselves in maintaining friendly inter-firm relationships. We study the effect of guanxi orientation on boundary spanners’ behaviors and the mechanism of how guanxi orientation influence inter-firm relationship quality. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual model.

This study collected survey data from distributors of cellphone industry. Distributors are uneven in size and from different regions. The respondent in this study is the purchasing manager (or owners) of 613 distributors, directly involved in the bilateral operations of cellphone brands. Cellphone industry is in line with research objectives because of the high competitiveness of the market and pervasive use of guanxi in economic exchanges. Purchasing managers in cellphone industry would like to develop guanxi networks as a resource to get more preferential terms. Measures were deprived from academic literature and were made some changes to adapt this study context. Interviews with distributor managers are conducted to better adapt questionnaire items before formal survey. Reliability and validity of all measures were tested.

Instrumentation

The study data collection consisted of three stages. Firstly, before designing the final questionnaire, we selected 45 managers of distributors from Beijing and Hebei areas as pre-test subjects and conducted semi-structured personal interviews with these managers in order to develop an understanding of guanxi, boundary spanning interactions, and inter-organizational relationship in the manufacturer-distributor dyads. Secondly, based on previous tests, we revised the questionnaires in English. A double-blinded translation was followed when translating the items from English to Chinese.

All measures used a Likert response scale ranging from 1(strong disagree) to 5 (strong agree). All constructs and measures used in the study exhibit satisfactory psychometric properties in Chinese business context based on previous interviews. Thirdly, we began the data collection with the distributors. To increase sample validity, a simple random sampling method was employed to identify distributors with average monthly sales of more than 200 cellphones, resulting in qualified 613 distributors nationwide.

Questionnaires were sent to the respondents by pre-paid mail. To encourage participation, we offered to provide a report of the research results. A statement of confidentiality was included in the cover letter of the questionnaire. To ensure the efficiency and validity of answering questions, the respondents are mostly senior managers who directly dealt with the counterparts and are familiar with their own firms’ and cooperative partners’ information. Respondents were required to mail the finished questionnaires to the address pre-written on the envelope. In the end, we collected 342 qualified questionnaires (incomplete or unqualified questionnaires are excluded in advance), with effective recovery rate of 55.8%.

Sample characteristics

In the final sample, qualified respondents are from various regions located in 27 provinces of China, indicating variations in regions. They sell different brands of cellphone and are responsible for implementing cellphone manufacturers’ marketing and sales promotion activities. Among respondents, 78.1% of them are male, 57.9% are senior managers, 30.4% are middle managers, and 11.7% are from other positions. Respondents’ average working years are 4.96 years, with 60.8% of them longer than 3 years (31.9% longer than 5 years), long enough to know trading partners and build cooperative relationships.

Nonresponse bias

To test for nonresponse bias, we compared firm attributes (size, revenues, and relationship length) of respondent distributor and firms which did not return their questionnaires or declined to participate the survey. None of the results were significant, indicating the absence of nonresponse bias.

Measures

The constructs in this study are derived from prior literature and adapted to the study specific research context. Details and the assessment results of each constructs used in the study are listed in the Appendix. The measure for guanxi orientation uses items of Su et al. (2009). Interpersonal liking and frequency of interactions are measured through the scale developed by Nicholson et al. (2001). Inter-firm support is adapted from scales used by Lusch and Brown (1996) and Heide and John (1990). Conflict is measured from Kumar et al. (1995) and long-term orientation is measured from Ganesan (1994). Control variables (relationship length and mutual dependence) are considered to influence outcome variables (conflict and long-term orientation). To control for the effects, respondents were asked to indicate how long the relationship has kept and dependence structure. Mutual dependence was measured by adding scores on the item “dependence on the partner” and “partner dependence”, measurements from Jap and Ganesan (2000).

Measure reliability and validity

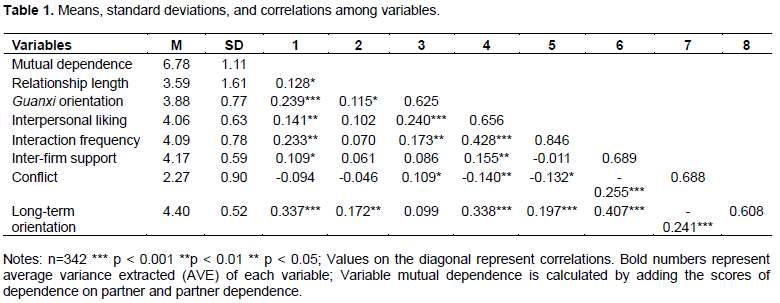

Means, standard variances, and correlations are shown in Table 1. Reliability and validity index of scales are shown in the Appendix. Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha index. The results for all constructs were from 0.698 to 0.854, greater than the cutoff point of 0.6, ensuring good internal consistency.

Composite reliability of each construct was in the range from 0.832 to 0.917 (>0.700), demonstrating high construct reliability. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) is conducted to assess the overall fitness of the model. The results show satisfactory fitness (χ2/df=1.461, RMSEA=0.037, CFI=0.970,IFI=0.971, TLI=0.964). The factor loadings of each items were mostly higher than 0.7 (with a few exceptions higher than 0.5), indicating appropriate construct validity. Average variance extracted (AVE) values for each constructs are higher than 0.50 (control variable mutual dependence is lower than than 0.50, but does not influence the fitness of the whole model), suggesting appropriate convergent validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

Finally, as a test of discriminant validity of the constructs, we compare the correlation between constructs with the square root of AVE. The results showed that the square root of the AVE for each construct is higher than the correlations, indicating a satisfactory level of discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). The Appendix showed the final constructs, items, reliability and validity index (Appendix 1).

Structural relationships in the conceptual model were tested by structural equation modeling (SEM) with AMOS 22. The maximum likelihood fitting function was used to estimate parameters and test proposed hypotheses. Structural equation modeling is often used to assess unobservable latent constructs, with measurement items treated as observed variables of each construct. Correlational results simultaneously within a framework were examined which enabled us to control measurement error. Results are shown in Figure 2.

As predicted, firm’s guanxi orientation is positively related to interpersonal liking (0.203, p<0.01) and interaction frequency (0.220, p<0.01) between boundary spanners. For interpersonal liking and interaction frequency, the more frequently boundary spanners interact, the more closer they are with each other (0.483, p<0.001).

Results aforementioned support H1a, H1b and H1c. Support of H1 identified that under the influence of organizational values guanxi orientation, boundary spanners would like to develop guanxi networks and implement guanxi building activities.

As a result, emotional attachment between boundary spanners is deepened. From distributors’ internal organization to external trading partner, interpersonal liking between boundary spanners has positive influence on inter-firm support (0.336, p<0.001), proving H2a. However, interaction frequency has no direct effect on distributor’s support, therefore H2b is not proved.

Lastly, from intra- to inter-organization, when boundary spanners of distributors provide essential support to the bilateral relationship, perceived conflict will be reduced (-0.319, p<0.001)and willingness to longer-term orientation will be increased (0.538, p<0.001), supporting H3a and H3b. The effect size of inter-firm support on long-term orientation is larger than on conflict. Boundary spanners take on the role of connecting and bridging partner firms, who function as inter-organizational ties.

In summary, guanxi orientation deepens relationship quality between boundary spanners from each side, appropriate enough for providing inter-organizational support, and then improves bilateral firm-level relationship development, decreasing conflict and enhancing long-term orientation. We observed indirect effects between constructs:

1. Guanxi orientation→inter-firm support. When we put the two variables independently, guanxi orientation has no positive effect on inter-firm support. In the whole model, guanxi orientation has no any direct effect on inter-firm support either. When we tried to add a connection link between guanxi orientation and inter-firm support in the whole model, neither of the coefficients of interpersonal liking and interaction frequency had any change. However, indirect effect exists (as 0.072 >0.05, significant evidence for indirect effects), indicating that guanxi orientation as one of the organizational values, impacts the firm-level support through the behaviors of intra-firm boundary spanners.

2. Interaction frequency→inter-firm support. As we found insignificant effect between the two constructs, we test whether interaction frequency has indirect effect on inter-firm support, say through interpersonal liking. Results show that coefficient of the indirect effect is 0.162, significantly higher than 0.05, demonstrating the path “interaction frequency---interpersonal liking---inter-firm support”.

3. Interpersonal liking→long-term orientation (conflict), through independent tests. We found the partial mediating role of inter-firm support. Interpersonal liking impacts long-term orientation and conflict directly (0.397 for long-term orientation, p<0.001; -0.182 for conflict, p<0.001). However, when inter-firm support is added, the direct coefficients tend to decrease (0.304 for long-term orientation, p<0.001; -0.177 for conflict, p<0.05). The connection between interpersonal liking and long-term orientation (conflict) provides an alternative for building inter-organizational relationship.