Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

There are qualitative studies aimed at identifying the problems encountered in the course of preparing individualized education programs (IEP). However, these studies are conducted with only a few participants. There is a need to test the results on a larger sample size. A questionnaire based on findings of interview techniques, used in qualitative research methodology, is developed. Using this questionnaire will identify the actual problems based on wider sample size, creating guidance for the required measures and actions. Thus, the purpose of this study is to identify the processes of preparing individualized education programs by special education teachers and of the problems they encounter. The sample group for this study, which utilized cross-sectional screening methods, is 1,000 teachers working in the special education field. At the end of the study, in addition to characteristics of IEP planning, performance measurement and IEP drafting by teachers, findings on problems faced due to teacher, room, material, parent, student, and personnel, in the course of preparation of IEP, were identified.

Key words: Individualized education program, individualized instruction plan, problems, questionnaire, cross-sectional screening.

INTRODUCTION

Individualized education programs (IEP) are special education programs, developed in writing, by an educational institution specifically for a student with disabilities, intending to meet the special needs and requirements of the students, teachers, and parents (Gibb and Taylor, 2016; Vuran, 2000). IEPs also referred to as complete service plans, are plans in which all services to be provided to students with disabilities are planned and coordinated (Fiscus and Mandell, 2002; Özyürek, 2004).

IEP covers the present levels of educational performance of the student in areas affected by the disability, annual goals and short-term objectives, description of the needed special education and related services, description of general curriculum areas the students can participate in, assessment period, and information on how and how often the parents will be informed (Pierangelo and Giuliani, 2007; Siegal, 2003).

Individualized instruction plans (IIP) are plans that are developed based on IEP and describe in detail the education to be carried out by teachers with the student. Common elements of IEP and IIP are present levels of educational performance of the student, annual goals, and short-term objectives. IIP, differing from IEP, contains such information as instructional goals, instructional method, materials, prompt level, reinforcement type and schedule, assessment method and, frequency (Fiscus and Mandell, 2002; Özyürek, 2004). For the sake of fluency in this article, we have opted to use only abbreviations of both of these terms. The IEP preparation process comprises three stages; planning, determination of performance level, and drafting.

IEP development planning

Collection of information

The first step in the determination of performance level is the collection of information about the student. First, to get to know the student, all existing records must be collected, filed, and reviewed. Documents suggested for this review are medical and health information, school reports or development reports indicating the school’s success, student personal file, etc. (Downing, 2010; Ireland, 2006). In addition, interviews are held with the student’s parents, present teacher or previous teachers, school counselor, and other school personnel who may have student information, or with the student himself/herself to learn his/her prioritized needs. Observation of the student at different times of day and in different environments also provides significant information about the student (Browder et al., 2011; Downing, 2010; Ireland, 2006). Furthermore, review of standardized test results such as intelligence tests, communication, and language skills assessment tests, applied in the previous years, and developmental scale results such as Denver, Portage, etc., and criterion-referenced tests applied in the previous instruction period, and if any, student’s portfolio and portfolio development reports are also helpful and useful for getting to know the student (DM Browder et al., 2011; Gürsel, 2000; Gürsel and Vuran, 2010).

IEP planning meetings

IEP team members participate in IEP planning meetings. IEP team members consist of the educational institution’s directors, school counselor, psychological counselor, the teacher assigned for preparation of education program, educators who play a role in the education of the student outside the educational institution, and teachers, classroom teachers and/or branch teachers who have taught the student in previous years, support service professionals who provide the support needed by the student such as physiotherapists, speech-language therapists, occupational therapists, student’s parents, and the student himself/herself. IEP meetings are repeated several times during the year for exchange of information among team members and/or for assessment of the development of the student prior to preparation of IEP (Batu, 2000; Blackwell and Rossetti, 2014; Bryant et al., 2008; Gibb and Taylor, 2016; Winterman and Rosas, 2014).

Determination of performance level

Preliminary assessment

Following the collection of general information about the student, more systematic work is performed for the guidance of planning of instruction. The first study performed is preliminary assessment activity. Preliminary assessment activities are rough assessments performed without entering into details for both determining the strong and weak skills of the student in the developmental areas dimension, and identifying the units and subjects the student did or did not learn in the curriculum courses. Developmental scales providing systematic information are suggested to be used for preliminary assessment of student in developmental areas (Browder et al., 2011; Gürsel, 2000; Ireland, 2006; Siegal, 2003). Included among the main developmental scales used in Turkey are Denver Developmental Screening Inventory, Ankara Developmental Screening Inventory (AGTE), Gazi Early Childhood Assessment Tool (GEÇDA), Portage Developmental Assessment Inventory, Küçük Ad?mlar Developmental Screening Inventory, and Early Development Phases Inventory (EGE). In Turkey, education programs and performance measurement forms, published by the Special Education General Directorate of the Ministry of National Education, are used for curriculum-based preliminary assessment. The programs and forms include “Special Education and Rehabilitation Centre Mentally Disabled Individuals Support Education Program”, “Performance Measurement Form for Individuals with Speech and Language Disturbances”, “Performance Measurement Form for Individuals with Special Learning Disability”, “Performance Measurement Form for Individuals with Pervasive Developmental Disorders”. In addition, development and curriculum preliminary assessment forms prepared by the related field teachers themselves by scanning the body of literature or curriculum program and by taking into consideration the peculiarities and general levels of students of their own classes are also used.

Detailed assessment

Weak skills determined as a result of preliminary assessment are prioritized, and detailed assessment is started on skill level. Detailed assessment on skill level is performed by means of criterion-referenced tests. In criterion-referenced tests developed based on skill analysis, concept analysis, or unit analysis, a certain knowledge, skill or subject may be accepted to have been learned only if and to the extent, it meets the targeted mastery level criteria (Gürsel, 2000; Ünal, 2017). In IEP, criterion-referenced tests are used basically for two purposes. First, these tests make a significant contribution to the planning of individualized instruction by ensuring detailed assessment of the student in terms of a single skill/task, thus determining the steps of that skill/task the student can or cannot do, and identification of the level of help the student needs for fulfilment of the steps that the student could not do. Secondly, benchmarks determined in the student’s IEP make it possible to monitor the progress of the student towards annual goals and short-term objectives. Therefore, it is important for teachers entrusted with the task of preparation of IEP to know how to prepare and apply criterion-referenced tests (Browder et al., 2011; Bryant et al., 2008; Gürsel and Vuran, 2010).

Collection of information about the student, use of preliminary assessment forms and performance of detailed assessments on each of the weak skills to determine the student’s performance level is a time-consuming process.

IEP drafting

Scope of IEP

IEP covers mainly the areas of development and curriculum. Included among the main developmental areas are cognitive, social, motor, language skills, and daily life and self-care abilities. Scope of IEP changes according to student’s age and degree of effects of disability. While it is limited to only developmental areas in the early childhood period, at the preschool age range, preschool curriculum programs are also added (Browder et al., 2011; Bryant et al., 2008; Erba?, 2000). As the student grows older, in addition to the developmental areas, curriculum program areas compatible with age groups are also included in the IEP. Regardless of the age of the student, as the student is affected by disability, developmental areas which may negatively affect the student’s educational performance are included in the program (Ireland, 2006; Siegal, 2003; Winterman and Rosas, 2014). Therefore, to keep the scope of IEP of a student affected from disability limited to only curriculum areas, and to disregard the fact that there may also be deficiencies in student’s developmental areas cause the preparation of an unrealistic IEP.

Parts of IEP

IEPs, also known as complete service plans, are programs prepared to meet the needs and requirements of students affected by disability and their parents and teachers and contain the planning of all services to be provided to the students. An IEP comprises the following parts: a) present levels of educational performance, b) annual goals and short-term objectives, c) planning for personnel, location, time and duration of the special education and support services, d) planning for the level, frequency and duration of the student’s participation in general education applications, and e) methods by which the student’s development will be measured, and the method and frequency of information sharing with the parents (Downing, 2010; Gibb and Taylor Dyches, 2016; Siegal, 2003; Vuran, 2000). On the other hand, IIPs are developed based on IEP and contain detailed planning regarding instruction to be provided to the student. An IIP covers the following: a) performance level, b) annual goals, short-term objectives, benchmarks, c) instruction materials, d) instructional adaptations, e) instructional method, f) prompt levels, g) reinforcement types and schedules, and h) assessment method, frequency, and criteria (D. M. Browder et al., 2011; Fiscus and Mandell, 2002; Gibb and Taylor, 2016; Winterman and Rosas, 2014).

Preparation of IEP specifically for each student with special education needs is made a legal obligation by the Decree-Law no. 573 enacted and issued in 1997. How the IEP will be prepared is taught in the course titled “Preparation of Individualized Education and Transitory Education Programs” included in the curriculum of Special Education Departments of universities. However, due to the insufficient number of special education teachers trained in special education area, in addition to special education teachers, preschool education teachers, classroom teachers, etc. teachers from other areas are also assigned in this area. Some problems may be faced in the process of preparation of IEP. Some studies have been conducted for the identification of problems encountered in the course of preparation and application of IEP in the country. As a result, the problems encountered in the course of preparation and application of IEP have been put forth generally under the headings of teacher (Bafra and Karg?n, 2009; Camadan, 2012; Çimen and Eraltay, 2010; Pekta?, 2008; Y?lmaz and Batu, 2016), location (Avc?o?lu, 2009; Çimen and Eraltay, 2010; Çuhadar, 2006; Pekta?, 2008; Y?lmaz, 2013), material (Ayano?lu and Gür-Erdo?an, 2019; Camadan, 2012; Çimen and Eraltay, 2010; Çuhadar, 2006; Y?lmaz, 2013), parent (Ayano?lu and Gür-Erdo?an, 2019; Çimen and Eraltay, 2010; Çuhadar, 2006; Pekta?, 2008; Yaman, 2017; Y?lmaz and Batu, 2016; Y?lmaz, 2013), student (Pekta?, 2008), personnel (Avc?o?lu, 2009), and IEP team (Avc?o?lu, 2009; Çuhadar, 2006; Pekta?, 2008; Y?lmaz and Batu, 2016). These studies have already made significant contributions. However, a fairly low number of participants in these studies do not allow generalization of study findings. Therefore, the problems faced in the field need to be examined from a wider point of view on the basis of data collected about a wider sample of participants by using a questionnaire. The questionnaire will be prepared based on qualitative research results already published in this area. The methods followed in the preparation of IEP’s both by special education teachers and by teachers from other areas but assigned in the special education area, and types of problems encountered by them during this process will surely shed a light on the measures that need to be taken. It will further make it possible not only to determine the difficulties faced and the supports such as materials or education needed by teachers working in special education area in the course of preparation of IEP but also to develop suggestions for arrangement of course contents and hours in curriculum programs designed for training special education teachers.

The purpose of this study is to determine the processes of preparation of IEP by teachers working in special education area, and the problems encountered by them. Within this framework, the following study questions are asked to teachers working in special education area:

a. Which types of planning studies do they perform in order to develop IEP?

b. Which types of studies do they perform in order to determine performance level?

c. What are the scope and parts of IEP prepared by them?

d. What are the problems encountered during the preparation of IEP?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study model

In this study, cross-sectional screening research, as a quantitative research method, is used. Research covering the observation of the situation of a case or a sample at a certain time is called cross-sectional screening research. This method resembles taking a snapshot of a population because the data collection process is conducted at one time (Metin, 2014). In its meeting no. 8-19, with a date of approval of 15.09.2021, Marmara University Institute of Educational Sciences Research and Publication Ethics Committee has discussed this study, and decided by unanimous vote that this study is non-objectionable in ethical terms.

Population and sample group

The population of this study consists of teachers working in special education centers or special rehabilitation centers of the Ministry of National Education in Istanbul in 2021. The sample group consists of 1,000 volunteer teachers accessible face to face or online based on the accessibility.

Participants

Information on gender, age, education and profession of participants is as detailed below: Gender and age: 710 (71%) of participants are women, and 290 (29%) are men. Ages of participants vary from 20 to 60 (M=32.34, SD=6.39). A review of distribution of participants in ages reveals the following: 20-30 ages (n=525, 52.5%), 31-40 ages (n=328, 32.8%), 41-50 ages (n=108, 10.8%), 51-60 ages (n=27, 2.7%) and 61-70 (n=12, 1.2%). Education level and area of graduation: 6% of participants hold associate’s degrees (n= 63), 84% undergraduate degrees (n=833), 10% postgraduate degrees (n=95) and only two of them hold doctorate degrees. Distribution of areas of graduation of participants is as follows: teacher of mentally handicapped (n=320, 32%), classroom teacher (n=147, 14.7%), preschool education teacher (n=75, 7.5%), child development and education teacher (n=70, 7%), psychological counselling and guidance (n=43, 4.3%), teacher of hearing-impaired (n=36, 3.6%), teacher of visually-impaired (n=27, 2.7%) and others (music, mathematics, sociology, fine arts, physical training, history, geography, etc.) (n=282, 28.2%). Period of Service: Periods of service of participants vary from 4 months to 28 years (M=11, SD=11). A review of these periods of service reveals that 22 are less than 1 year (3%), 308 within a range of 1 to 4 years (38%), 215 within a range of 5 to 9 years (27%), 139 within a range of 10 to 14 years (17%), 55 within a range of 15 to 19 years (7%), and 65 equal to or above 20 years (8%). School Status: 75% of participants (n=750) are working in public schools, 23.5% (n=235) in private schools, and 1.5% (n=15) in foundation schools. School Types: 24.4% (n=244) of participants work in special education and rehabilitation centers, 23.2% (n=232) in special education classes, 16.7% (n=167) in special education work application centers III. Stage (high school / severe – moderate disabilities), 11.2% (n=112) in special education vocational education centre (high school / slight mental disabilities – autism), 9% (n=9) in special education school (kindergarten + primary school + secondary school), 8.1% (n=81) in special education application centers, Stage 1 (primary school / severe – moderate disabilities), and 7.4% (n=74) in special education application centers, Stage 2 (secondary school / severe – moderate disabilities).

Data collection tool

Features of and development of the questionnaire

In this study, a tripartite questionnaire titled “Identification of Processes of Preparation of Individualized Education Programs and Problems Encountered” developed by the researcher is used. The questionnaire is composed of three parts, namely demographic data, determination of processes of preparation of IEP, and determination of problems encountered during the preparation of IEP.

The first part contains demographic questions (five closed-end and four open-ended questions) aiming to determine the province and township of work, age, gender, education level, area of graduation, period of service, the status of school, and type of the school of the participant. The second part contains ten closed-end questions aiming to determine IEP preparation processes such as IEP development planning, performance level determination, and IEP drafting by participants. The third part contains seven closed-end questions aiming to determine the teacher, location, material, parent, student, personnel and IEP team sourced problems encountered by participants in preparation of IEP. Choices of answers to closed-end questions are designed based on results of interview-based research conducted in connection with the subject (Avc?o?lu, 2011; Camadan, 2012; Ç?k?l? et al., 2020; Çimen and Eraltay, 2010; Çuhadar, 2006; Pekta?, 2008; ?ahin and Gürler, 2018; Vuran, 1996; Y?lmaz and Batu, 2016, 2016b). In both parts, participants are allowed to mark more than one choice, and each question contains an “other” choice where participants may express their own opinions and comments thereon. The resulting questionnaire is sent to five special education specialists working in the field for control in terms of scope and comprehensibility, and to one measurement and evaluation specialist for eligibility check, and the required corrections are made in tandem with the opinions and other feedback received from them.

Analysis of data

Average, standard deviation, and percentage values of demographic data collected from participants are calculated. An analysis of closed-end questions included in other parts, the number of participants marking certain choices contained in questions and the percentage of this number in the total number of participants are given.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Research findings are organized under four headings, planning of IEP development, determination of performance level, IEP drafting, and problems encountered in the course of preparation of IEP. The answers given by 1000 teachers participating in the research to the questions are shown with "n", the number of participants who chose that option on the basis of each question. It is aimed to show the trends on the basis of total participants in the tables. For this reason, since it is possible for the participants to mark more than one option in the questions and it is aimed to show how many participants preferred the option among the total participants; the frequency was calculated by calculating the rate of preference for each option among the total participants, and the percentage value was determined.

Planning of IEP development

The planning work for IEP development consists of the collection of information aimed to get to know the students, and IEP team meetings held with individuals who contribute to the education and instruction of the students to determine what should be included in the contents of IEP.

Collection of information

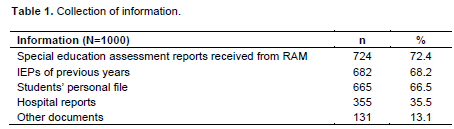

The collection of information aimed to get to know the students includes observation and interviews in addition to reviewing the student-related documents. Participants are asked: “Which records and reports do you examine and review related to the student before preparation of IEP?” (Table 1).

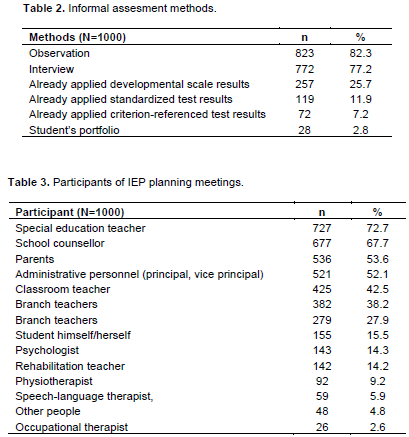

In this question, 72.4% of participants say they examine special education assessment reports received from RAM, while 68.2% refer to IEPs of previous years, 66.5% to student’s personal file, 35.5% to hospital reports, and 13.1% to other documents. Participants are asked “Which assessment work do you perform in order to get to know the student?” (Table 2)

In this question, 82.3% of participants make mention of observations, 77.2% of interviews, 25.7% of already applied developmental scale results, 11.9% of already applied standardized test results, 7.2% of already applied criterion-referenced test results, and 2.8% of student’s portfolio. Yaman (2017) argues that educational diagnosis received from RAM occasionally does not reflect the truth, is not comprehensible, and fails to inform the teacher well as to what the teacher should do. It is noted that participants used informal assessment methods such as observations and interviews but opted less to the review of already applied developmental scale, standardized test and criterion-referenced test results, or student’s portfolio. In Pekta? (2008)’ study, it is stated that teachers deem the family interview forms filled in the interviews with parents adequate for preliminary assessment and do not separately use a preliminary assessment form. Similarly, Avc?o?lu (2011a) reports that the interview is limited to the student, and only very few teachers hold an interview with parents.

Participants of IEP planning meetings

IEP planning meetings are meetings held with the IEP team in the course of the IEP development process. The purpose of these meetings is to bring those making contributions to the student’s education together to assess the student in a multi-dimensional, sophisticated and holistic manner and to decide on the contents of the student’s IEP (Table 3). Answers given to the question: “Who participates in your IEP meetings?” asked to participants are as follows: 72.7% special education teacher, 67.7% school counsellor, 53.6% parents, 52.1% administrative personnel (principal, vice principal), 42.5% classroom teacher, 38.2% branch teachers, 15.5% student himself/herself, 14.3% psychologist, 14.2% rehabilitation teacher, 9.2% physiotherapist, 5.9% speech-language therapist, 4.8% other people, and 2.6% occupational therapist.

However, it is reported in Yaz?c?o?lu (2019)’s study that according to arguments of school counsellors, IEP meetings are not organized, IEP team members do not enter into cooperation, and parents cannot play an effective role therein even though they are encouraged by the school management to participate in such meetings.

Determination of performance level

In the determination of annual goals and short-term objectives to be included in the IEP, it is fairly important to correctly measure the performance level of the student. Determining the performance level is done in two consecutive stages, preliminary assessment and detailed assessment.

Preliminary assessment

Preliminary assessment work represents the first stage of determining the performance level. Although, preliminary assessment work is fairly important in the determination of skills required for a detailed assessment, to limit the determination of performance level only by preliminary assessment work points to a serious limitation.

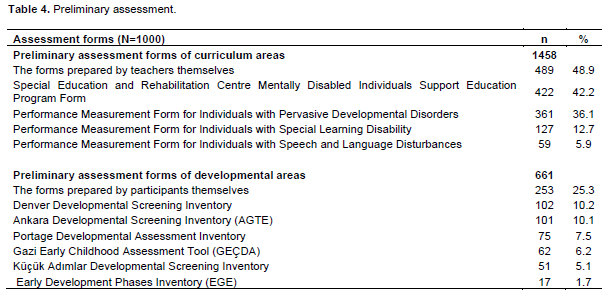

In the question containing choices of names of preliminary assessment forms commonly used in the field by participation for preliminary assessment of their students in curriculum and developmental areas, the participants are asked: “Which forms do you use to assess the curriculum and developmental areas in the course of a preliminary assessment?” (Table 4).

It is noted that participants generally use preliminary assessment forms of curriculum areas (n=1458) more than preliminary assessment forms of developmental areas. Forms most commonly used in the assessment of curriculum areas are the forms prepared by teachers themselves (48.9%), followed by “Special Education and Rehabilitation Centre Mentally Disabled Individuals Support Education Program Form” (42.2%), “Performance Measurement Form for Individuals with Pervasive Developmental Disorders” (36.1%), “Performance Measurement Form for Individuals with Special Learning Disability” (12.7%) and “Performance Measurement Form for Individuals with Speech and Language Disturbances” (5.9%). Likewise, the forms most commonly used by participants in the assessment of developmental areas are the forms prepared by participants themselves. In addition, for preliminary assessment of developmental areas, developmental scales such as Denver Developmental Screening Inventory (10.2%), Ankara Developmental Screening Inventory (AGTE) (10.1%), Portage Developmental Assessment Inventory (7.5%), Gazi Early Childhood Assessment Tool (GEÇDA) (6.2%), Küçük Ad?mlar Developmental Screening Inventory (5.1%), and Early Development Phases Inventory (EGE) (1.7%) are noted to be used.

Findings regarding the use of preliminary assessment forms by teachers are considered to be consistent with the findings of Pekta? (2008). Mentally disabled children also have disabilities in many developmental areas in varying different degrees (Browder et al., 2009; Browder, 2001; Browder et al., 2011). In the education of these children, work on the disabilities in developmental areas needs to be prioritized to be planned and carried out. A preliminary assessment made first and/or only in curriculum areas without developing their disabilities encountered in developmental areas leads to the preparation of an IEP covering only curriculum areas (Avc?o?lu, 2011; Bafra and Karg?n, 2009).

Detailed assessment

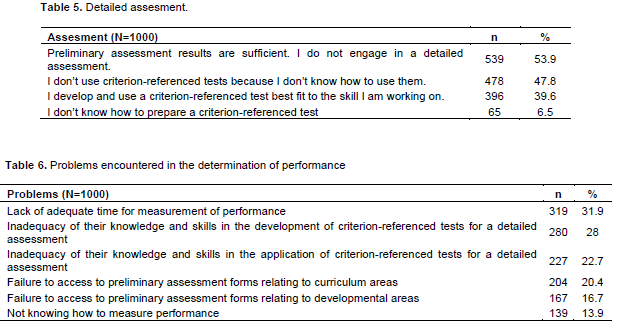

In order to determine whether participants use criterion-referenced tests, the participants are asked: “Do you use criterion-referenced tests for determination of your student’s performance level?” (Table 5).

This question is answered as “Preliminary assessment results are sufficient. I do not engage in a detailed assessment.” by 53.9% of participants, and as “I don’t use criterion-referenced tests because I don’t know how to use them.” by 47.8%, and as “I develop and use a criterion-referenced test best fit to the skill I am working on.” by 39.6%, and as “I don’t know how to prepare a criterion-referenced test. For this reason, I use ready-made criterion-referenced tests.” by 6.5%. In light of these findings, it may be opined that teachers working in special education areas are developing IEP without using criterion-referenced tests.

It is possible to say that these findings regarding the use of criterion-referenced tests are greatly similar to the results of Pekta? (2008). Pekta? (2008)’study emphasizes that 16% of graduates of a special education program and 8% of graduates of other different programs are using criterion-referenced tests.

Problems encountered in the determination of performance

Participants are asked to select from the choices of problems encountered in the determination of performance in the course of preparation of IEP (Table 6).

The problems encountered are expressed as “lack of adequate time for measurement of performance” by 31.9% of participants, and as “inadequacy of their knowledge and skills in the development of criterion-referenced tests for a detailed assessment” by 28%, and as “inadequacy of their knowledge and skills in the application of criterion-referenced tests for a detailed assessment” by 22.78%, and as “failure to access to preliminary assessment forms relating to curriculum areas” by 20.4%, and as “failure to access to preliminary assessment forms relating to developmental areas” by 16.7%, and “not knowing how to measure performance” by 13.9%.

IEP drafting

Determination of the performance of level of the students is followed by drafting of an IEP for the students. Under this heading, in addition to the scope of IEP’s prepared by participants, and the parts included in an IEP, the findings relating to IEP preparation time, method followed in drafting of IEP, and challenges faced in drafting of IEP are included.

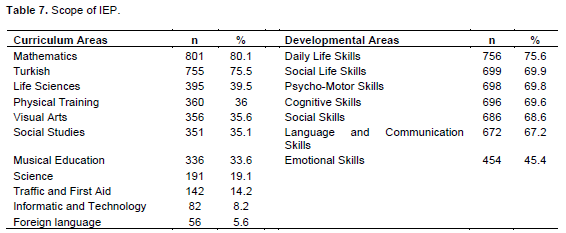

Scope of IEP

A review of scope of IEPs prepared by teachers working in special education area reveals that the most commonly used curriculum areas are mathematics (80.1%) and Turkish (75.5%), followed by life sciences (39.5%), physical training (36%), visual arts (35.6%), social studies (35.1%), musical education (33.6%), science (19.1%), traffic and first aid (14.2%), informatics and technology (8.2%) and foreign language (5.6%). A review of developmental areas inserted by participants in their IEPS reveals that the most commonly used developmental area is self-care and daily life skills (75.6%), followed by social life skills (69.9%), psycho-motor skills (69.8%), cognitive skills (59.6%), social skills (68.6%), language and communication skills (67.2%) and emotional skills (45.4%) (Table 7).

In the evaluation of these findings, if we take into consideration that the preferred forms for preliminary assessment are the forms aiming to assess curriculum areas, it may be said that IEP scope is also mainly inclined to curriculum areas. Avc?o?lu (2009)’s study reporting the opinions of RAM managers that IEP contents are not concentrated on the development of communication and social skills also supports the findings of this study.

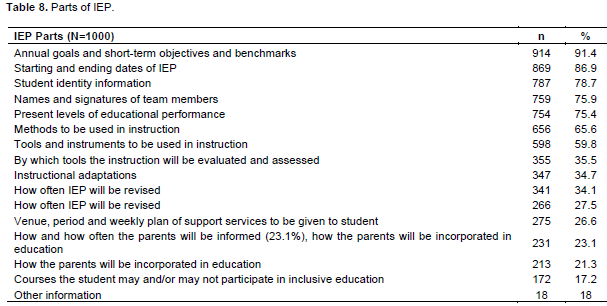

Parts of IEP

The question of “Which parts do you insert in IEP prepared by you?” asked participants are answered as follows (Table 8): annual goals and short-term objectives and benchmarks (91.4%), starting and ending dates of IEP (86.9%), student identity information (78.7%), names and signatures of team members (75.9%), present levels of educational performance (75.4%), methods to be used in instruction (65.6), tools and instruments to be used in instruction (59.8%), by which tools the instruction will be evaluated and assessed (35.5%), instructional adaptations (34.1%), how often IEP will be revised (27.5%), venue, period and weekly plan of support services to be given to students (26.6%), how and how often the parents will be informed (23.1%), how the parents will be incorporated in education (21.3%), courses the student may and/or may not participate in inclusive education (17.2%) and other information (18%).

A look at the parts of plans prepared by teachers working in special education area demonstrates that these parts mostly comprise contents of an IIP such as present levels of educational performance, annual goals and short-term objectives, benchmarks, instructional methods, materials, tools of evaluation and assessment, etc. On the other hand, it may be said that elements of an IEP such as venue, period and weekly plan of support services, how and how often the parents will be informed, and courses the student may and/or may not participate in inclusive education are less commonly used in the plans prepared by teachers.

Thus, it is concluded that these findings are also consistent with those of Avc?o?lu (2011).

IEP preparation time

The question “How much time does it take for you to prepare an IEP for a student?” asked participants is answered as one week by 28.3% of participants, one month by 24%, a few days by 23.1%, two weeks by 14% and three weeks by 13.6%.

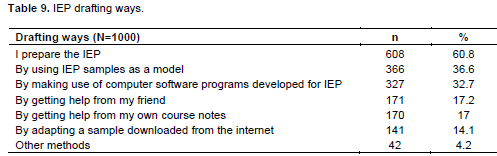

IEP drafting ways

The question “Which methods do you follow in preparation of IEP?” asked participants is answered as “I prepare the IEP.” by 60.8% of participants, “by using IEP samples as a model” by 36%, “by making use of computer software programs developed for IEP” by 32.7%, “by getting help from my friend” by 17.2%, “by getting help from my own course notes” by 17%, “by adapting a sample downloaded from the internet” by 14.1% and other methods by 4.2% (Table 9).

These findings also are greatly consistent with the results of previous studies performed (Bafra and Karg?n, 2009; Y?lmaz and Batu, 2016).

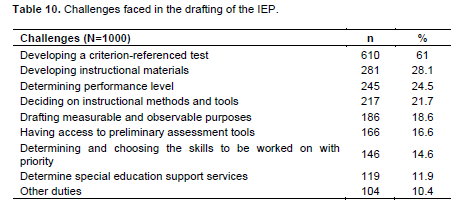

Challenges faced in the drafting of the IEP

Participants have given the following answers to the question: “What are the challenges you faced in the drafting of the IEP?” (Table 10): developing a criterion-referenced test by 61%, developing instructional materials by 28.1%, determining performance level by 24.5%, deciding on instructional methods and tools by 21.7%, drafting measurable and observable purposes by 18.6%, having access to preliminary assessment tools by 16.6%, determining and choosing the skills to be worked on with priority by 14.6%, to determine special education support services by 11.9% and other duties by 10.4%.

The findings of previous related studies may be listed as “determination of performance level” (Pekta?, 2008), development of instructional materials (Ayano?lu and Gür-Erdo?an, 2019; Pekta?, 2008; ?ahin and Gürler, 2018; Tekin and Ata, 2016), and drafting of purposes (Avc?o?lu, 2011; Kuyumcu, 2011).

Problems encountered in the preparation of IEP

Both preparatory work and IEP drafting for the development of an IEP require particular knowledge, skills, and experiences. A lot of problems may be encountered during this process. This heading deals with the findings relating to teacher, location, material, parent, student, personnel and IEP team-sourced problems encountered by participants in the process of preparation, and drafting of IEP.

Teacher

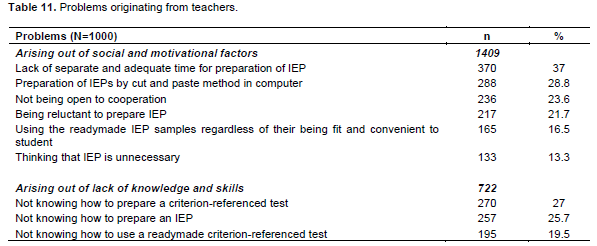

Participants are asked to select from choices of problems that may arise from a teacher in preparing the IEP (Table 11).

It is seen that the teacher-sourced problems expressed by the participants as the problems they face in preparation of IEP are focused on two main headings, arising out of social and motivational factors and arising out of lack of knowledge and skills. “Problems arising out of social and motivational factors” (n=1409) constitute the heading of problems most commonly expressed by participants. Under this heading, the problems are listed as “lack of separate and adequate time for preparation of IEP” (37%), “preparation of IEPs by cut and paste method in computer” (28.8%), “not being open to cooperation” (23.6%), “being reluctant to prepare IEP” (21.7%), “using the readymade IEP samples regardless of their being fit and convenient to student” (16.5%), and “thinking that IEP is unnecessary” (13.3%). The second group of teacher-sourced problems expressed to be encountered by participants in the preparation of IEP is composed of problems arising from lack of knowledge and skills of teachers (n=722). Included in this group are problems such as “not knowing how to prepare a criterion-referenced test” (27%), “not knowing how to prepare an IEP” (25.7%), and “not knowing how to use a readymade criterion-referenced test” (19.5%). Teacher-sourced problems expressed to be encountered in preparation of IEP by teachers working in special education area are greatly comprised of “problems arising out of social and motivational factors”. The basic reason is the “lack of separate and adequate time for preparation of IEP”, followed by “preparation of IEPs by cut and paste method on the computer”. Y?lmaz and Batu (2016a) emphasize that “not knowing how to prepare a criterion-referenced test” is the primary problem arising from the lack of knowledge and skills of teachers.

Room

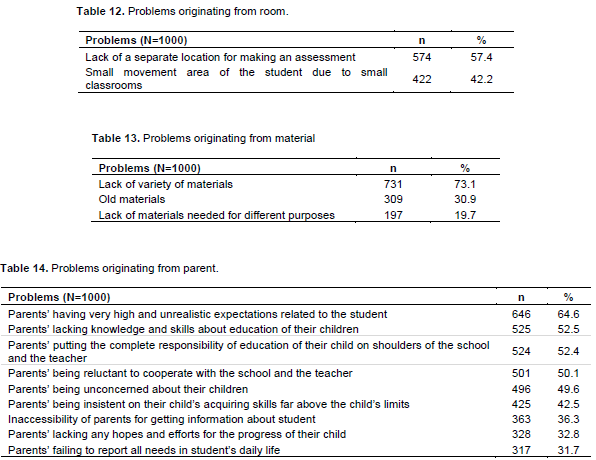

Participants are asked to select from choices of problems that may arise out of location in preparation of the IEP. Participants have expressed mainly two problems arising out of location in the process of preparation of the IEP (Table 12). They are “lack of a separate location for making an assessment” (57.4%) and “small movement area of the student due to small classrooms” (42.2%).

Material

Participants are asked to select from choices of problems that may arise from materials in preparation of the IEP (Table 13).

Participants have expressed mainly three problems arising from materials in the process of preparation of the IEP. They are “lack of variety of materials” (73.1%), “old materials” (30.9%) and “lack of materials needed for different purposes” (19.7%). These study findings are considered to be greatly consistent with results of previous related studies (Avc?o?lu, 2009; Camadan, 2012; Çimen and Eraltay, 2010; Çuhadar, 2006; Pekta?, 2008; Y?lmaz, 2013).

Parent

Participants are asked to select from choices of problems that may arise from parents in the preparation of the IEP. Participants have expressed a lot of problems arising out of parents in preparation of the IEP (Table 14).

The problems are led by “parents’ having very high and unrealistic expectations related to the student” (64.6%), and followed by “parents’ lacking knowledge and skills about education of their children” (52.5%), “parents’ putting the complete responsibility of education of their child on shoulders of the school and the teacher” (52.4%), “parents’ being reluctant to cooperate with the school and the teacher” (50.1%), “parents’ being unconcerned about their children” (49.6%), “parents’ being insistent on their child’s acquiring skills far above the child’s limits” (42.5%), “inaccessibility of parents for getting information about student” (36.3%), “parents’ lacking any hopes and efforts for the progress of their child” (32.8%) and “parents’ failing to report all needs in student’s daily life” (31.7%). It may be said that these findings are also greatly similar to the results of previous studies (Çimen and Eraltay, 2010; ?ahin and Gürler, 2018; Yaman, 2017; Y?lmaz and Batu, 2016; Y?lmaz, 2013).

Student

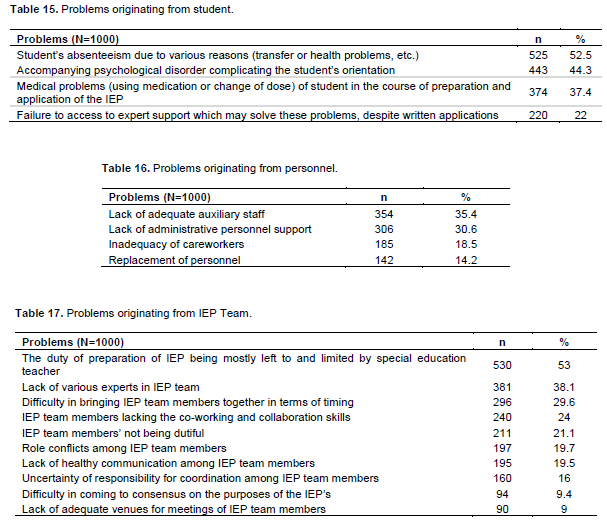

Participants are asked to select from choices of problems that may arise out of the student in the preparation of the IEP (Table 15).

Participants have expressed mainly four problems arising from the student in the preparation of the IEP. They are led by “student’s absenteeism due to various reasons (transfer or health problems, etc.)” (52.5%) and followed by “accompanying psychological disorder complicating the student’s orientation” (44.3%), “medical problems (using medication or change of dose) of student in the course of preparation and application of the IEP” (37.4%) and “failure to access to expert support which may solve these problems, despite written applications” (22%).

These findings are considered to be consistent with other study results (Camadan, 2012; Can, 2015; Çimen and Eraltay, 2010).

Personnel

Participants are asked to select from choices of problems that may arise out of personnel in preparation of the IEP. Participants have expressed mainly four problems arising from personnel in preparation of the IEP (Table 16). The personnel-sourced problems are “lack of adequate auxiliary staff” (35.4%), “lack of administrative personnel support” (30.6%), “inadequacy of careworkers” (18.5%), and “replacement of personnel” (14.2%).

IEP team

Participants are asked to select from choices of problems that may arise out of IEP team in preparation of the IEP. Participants have expressed a lot of problems arising out of the IEP team in preparation of the IEP (Table 17).

The IEP team-sourced problem most commonly marked by participants is “the duty of preparation of IEP being mostly left to and limited by special education teacher” (53%), and this problem is followed by “lack of various experts in IEP team” (38.1%), “difficulty in bringing IEP team members together in terms of timing” (29.6%), “IEP team members lacking the co-working and collaboration skills” (24%), “IEP team members’ not being dutiful” (21.1%), “role conflicts among IEP team members” (19.7%), “lack of healthy communication among IEP team members” (19.5%), “uncertainty of responsibility for coordination among IEP team members” (16%), “difficulty in coming to consensus on the purposes of the IEP’s” (9.4%), and “lack of adequate venues for meetings of IEP team members” (9%). These study findings may be said to show great similarities to the results of previous studies (Avc?o?lu, 2009; Çuhadar, 2006; Y?lmaz and Batu, 2016).

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, it may be said that the results of this study are significantly consistent with the results of other studies previously conducted in the special education area by using interview techniques based on qualitative research methods and by examining the opinions and comments of participants in depth. It is observed that although the plans prepared in practice correspond mainly to (IIP) in terms of contents, they are commonly named as (IEP), also known as Complete Service Plan. However, they do not cover support education services, information of families, and course/activity participation planning in inclusive education applications.

It is therefore required to introduce the existing preliminary assessment tools to teachers working in the special education area, and to give on-the-job training to and publish guidebooks for these teachers for skill/concept/unit analyses, preparation and application of criterion-referenced tests, drafting of present levels of educational performance of students based on results of said tests, drafting of annual goals/short-term objectives and benchmarks, and preparation of an IIP containing elements such as instructional methods, materials, prompt levels, reinforcement types, assessment methods, frequency, etc. This questionnaire to be reviewed by also making use of qualitative study findings newly introduced to the special education area may be repeated with greater numbers of participants. Furthermore, repetition of similar studies focused on special education professionals working with different child groups in need of special education, such as children with special learning disabilities, gifted children, etc. will ensure the determination of their specific requirements as well.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Avc?o?lu H (2009). Rehberlik ve Ara?t?rma Merkez (RAM) müdürlerinin tan?lama, yerle?tirme izleme, bireyselle?tirilmi? e?itim program? (BEP) geli?tirme ve kayna?t?rma uygulamas?nda kar??la??lan sorunlara ili?kin alg?lar? [Guidance and Research Center (GRC) managers' opinions about unexpected problems of identification, placement-follow up, IEP development, and integration practice]. Kuram ve Uygulamada E?itim Bilimleri Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice 12(3):2009-2031. |

|

|

Avc?o?lu H (2011). Zihin engelliler s?n?f ö?retmenlerinin bireyselle?tirilmi? e?itim program? (BEP) haz?rlamaya ili?kin görü?leri [Determination of mental handicapped class teachers' thought about learning, preparing and applying IEP]. Anadolu Üniversitesi E?itim Fakültesi Özel E?itim Dergisi [Anadolu University Faculty of Education, Journal of Special Education 12(1):39-53. |

|

|

Ayano?lu Ç, Gür-Erdo?an D (2019). School Administrators' Opinions on Preparation/Implementation of Individualized Education Plan (IEP) for Students with Special Needs. Journal of Special Education 20(4):699-706. |

|

|

Bafra LT, Karg?n T (2009). S?n?f ö?retmenleri, Rehber ö?retmenler ve Rehberlik Ara?t?rma Merkezi çal??anlar?n?n Bireyselle?tirilmi? E?itim Program Haz?rlama sürecine ?li?kin Tutumlar? ve Bu süreçte Kar??la?t?klar? Güçlüklerin Belirlenmesi [Investigating the attitudes of elementary school teachers, school psychologists and guidance research center personnel on the process of preparing the individualized educational program and challenges faced during the related process]. Kuram ve Uygulamada E?itim Bilimleri Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice 9(4):1933-1972. |

|

|

Batu ES (2000). Bireyselle?tirilmi? e?itim programlar?nda ekip çal??malar?na yer verilmesi [Team work when preparing individulaized educational programme]. In O. Gürsel (Ed.), Bireyselle?tirilmi? E?itim Programlar?n?n Geli?tirilmesi [Developing Individualized Educational Programes] Eski?ehir: Anadolu Üniversitesi Aç?k Ö?retim Fakültesi Yay?nlar?. pp. 31-44. |

|

|

Blackwell WH, Rossetti ZS (2014). The development of individualized education programs:Where have we been and where should we go now? Sage Open 4(2):2158244014530411. |

|

|

Browder D, Gibbs S, Ahlgrim-Delzell L, Courtade GR, Mraz M, Flowers C (2009). Literacy for students with severe developmental disabilities: what should we teach and what should we hope to achieve? Remedial and Special Education 30(5):268-282. |

|

|

Browder DM (2001). Curriculum and Assessment for Students with Moderate and Severe Disabilities. New York: Guilford. |

|

|

Browder DM, Spooner F, Jimenez B (2011). Standards-Based individualized education plans and progress monitoring. In D. Browder and F. Spooner (Eds.), Teaching Students with Moderate and Severe Disabilities. New York: The Guilford Press. |

|

|

Bryant DP, Smith DD, Bryant BR (2008). Teaching students with special needs in inclusive classrooms. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. |

|

|

Camadan, F. (2012). S?n?f ög?retmenleri ve s?n?f ög?retmeni adaylar?n?n kaynas?t?rma eg?itimine ve BEP haz?rlamaya ilis?kin öz- yeterliklerinin belirlenmesi [Determining primary school teachers' nad primary school pre-service teachers' self-efficacy beliefs towards integrated education and IEP preparation]. Elektronik Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi Electronic Social Science Journal 11(39):128-138. |

|

|

Can B (2015). Bireyselle?tirilmi? e?itim program? ile ilgili özel e?itim ö?retmenlerinin ya?ad?klar? sorunlar ve bu sorunlara yönelik çözüm önerileri (KKTC Örne?i)[Problems of special education teachers who are interested in individualized education program and solution proposals for these problems]. Yak?ndo?u Üniversitesi E?itim Bilimleri Enstitüsü [Near East University Atatürk Education Faculty Department of Special Education], Lefko?e. |

|

|

Ç?k?l? Y, Gönen A, Aslan Ba?c? Ö, Kaynar H (2020). Özel e?itim alan?nda görev yapan ö?retmenlerin bireyselle?tirilmi? e?itim program? (BEP) haz?rlama konusunda ya?ad?klar? güçlükler [The difficulties of teachers working in the field of special education in preparing individualized education program (IEP)]. OPUS Uluslararas? Toplum Ara?t?rmalar? Dergisi OPUS International Journal of Society Researches 15(10):1-1. |

|

|

Çimen Öztürk C, Eraltay E (2010). E?itim uygulama okuluna devam eden zihinsel engelli ö?rencilerin ö?retmenlerinin bireyselle?tirilmi? e?itim program? hakk?nda görü?lerinin belirlenmesi [Determining opinions of teachers of students with mental retardation attending an education application school on the individualized education plan]. Abant ?zzet Baysal Üniversitesi Dergisi Journal of Abant ?zzet Baysal University 10(2):145-159. |

|

|

Çuhadar Y (2006). ?lkö?retim okulu 1-5. S?n?flarda kayna?t?rma e?itimine tabi olan ö?renciler için bireyselle?tirilmi? e?itim programlar?n?n haz?rlanmas?, uygulanmas?, izlenmesi ve de?erlendirilmesi ile ilgili olarak s?n?f ö?retmenleri ve yöneticilerin görü?lerinin belirlenmesi [Determining the Views of the Form Masters and the Principals Concerning the Preparation, Implementation, Monitoring and Evaluation of the IEP for the Students that are Subject to Coalescence Education in Classes 1-5 of Elementary Education]. Zonguldak Karaelmas Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, Zonguldak. |

|

|

Downing JE (2010). Academic Instruction for Students With Moderate and Severe Intellectual Disabilities in Inclusive Classrooms. California: Corwin Press. |

|

|

Erba? D (2000). Var olan performans düzeyinin belirlenmesi ve yaz?lmas? [Determining and writing of the present levels of performance]. In: O. Gürsel (Ed.), Bireyselle?tirilmi? E?itim Programlar?n?n Geli?tirilmesi Developing Individualized Education Programmes. Eski?ehir: Anadolu Üniversitesi Aç?k Ö?retim Fakültesi Yay?nlar? pp. 69-80. |

|

|

Fiscus ED, Mandell CJ (2002). Bireyselle?tirilmi? E?itim Programlar?n?n Geli?tirilmesi (G. Akçamete, H. G. ?enel, and E. Tekin, Trans.): An? Yay?nc?l?k. |

|

|

Gibb GS, Taylor DT (2016). Guide to Writing Quality Individualized Education Programs (3rd. ed.). Boston: Pearson. |

|

|

Gürsel O (2000). Özel Gereksinimi Olan Çocuklar? De?erlendirme [Assesing The Children with Special Needs]. In: O. Gürsel (Ed.), Bireyselle?tirilmi? E?itim Programlar?n?n Geli?tirilmesi [Developing Individualized Education Programmes]. Eski?ehir: Anadolu Üniversitesi Aç?k Ö?retim Fakültesi Yay?nlar?. |

|

|

Gürsel O, Vuran S (2010). De?erlendirme ve bireyselle?tirilmi? e?itim programlar? geli?tirme. [Assessment and developing individualized education programme] In ?. H. Diken (Ed.), ?lkö?retimde Kayna?t?rma. [Inclusion at Primary School]. Ankara: Pegem Akademi. |

|

|

Ireland NCFSE (2006). Guidelines on the individual education plan process. Available at: |

|

|

Kuyumcu Z (2011). Bireyselle?tirilmi? e?itim plan? (BEP) geli?tirilmesi ve uygulanmas? sürecinde ö?retmenlerin ya?ad?klar? sorunlar ve bu sorunlara yönelik çözüm önerileri [Teachers' problems and solution they suggest related to these problems in the process of development and implementation of individualized education plan (IEP)]. Ankara Üniversitesi E?itim Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Ankara. |

|

|

Metin M (2014). Kuramdan Uygulamaya E?itimde Bilimsel Ara?t?rma Yöntemleri [Scientific Research Methods at Education From Theory to Practice]. Ankara: Pegem Akademi Yay?nc?l?k. |

|

|

Özyürek M (2004). Bireyselle?tirilmi? E?itim Program? Temelleri ve Geli?tirilmesi [Basis of Individualized Education Programme and Development] (1. Bask? ed.). Ankara: Kök Yay?nc?l?k. |

|

|

Pekta? H (2008). Özel e?itim programlar?ndan ve farkl? programlardan mezun ö?retmenlerin bireyselle?tirilmi? e?itim program? kullanma durumlar?n?n saptanmas? [The proficiency of the teachers who are graduated from the department of special education and the teachers who are graduated from departments other than special education in relation to preparing and practising individualized education schedule]. Gazi Üniversitesi E?itim Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Ankara. |

|

|

Pierangelo R, Giuliani G (2007). Understanding, developing, and writing effective IEPs: A step-by-step guide for educators. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. |

|

|

Siegal AL (2003). The Complete IEP Guide How to Advocate for Your Specila Ed Child (2nd. Edition ed.). Berkeley, CA: Nolo. |

|

|

?ahin A, Gürler B (2018). Destek E?itim Odas?nda ve Kayna?t?rma Ortamlar?nda Çal??an Ö?retmenlerin Bireyselle?tirilmi? E?itim Program? Haz?rlama Sürecinde Ya?ad?klar? Güçlüklerin Belirlenmesi [Determining the strengths of the preparation of the individual training program of teachers who are working in supporting and inclusive education]. Ad?yaman Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi Ad?yaman University Journal of Social Science Institute 29:594-625. |

|

|

Tekin ED, Ata S (2016). Okul öncesi ö?retmenlerinin bireyselle?tirilmi? e?itim program? haz?rlanmas?na ili?kin görü?leri [Preschool teachers' opinions/views on develoing the individualized education programme]. Trakya Üniversitesi E?itim Fakültesi Dergisi Trakya University Journal of Education Faculty 8(1):162-177. |

|

|

Ünal F (2017). Sosyal Bilgiler Ö?retiminin Uyarlanmas? I:Ünite Analizi ve Amaçlar?n Belirlenmesi [Modifiying teaching socail science I: Unit analsis and detemining goals]. In M. Sönmez Kartal and Ö. Toper Korkmaz (Eds.), Özel E?itimde Fen Bilgisi ve Sosyal Bilgiler Ö?retimi [Teaching Social Studies ans Science] Ankara: Pegem Akademi. |

|

|

Vuran S (1996). Bireyselle?tirilmi? ö?retim materyallerinin haz?rlanmas? [Preparing individualized instructional materials]. Anadolu Üniversitesi E?itim Fakültesi Dergisi Anadolu University Journal of Education Faculty 6(1):75-82. |

|

|

Vuran S (2000). Bireyselle?tirilmi? e?itim programlar? (BEP) [Individualized education programmes (IEP)]. In: O. Gürsel (Ed.), Bireyselle?tirilmi? E?itim Programlar?n?n Geli?tirilmesi. Eski?ehir: Anadolu Üniversitesi Aç?k Ö?retim Fakültesi Yay?nlar?. pp. 31-44. |

|

|

Winterman KG, Rosas C (2014). The IEP Checklist Your Guide to Creating Meaningful and Compliant IEPs. Baltimore, Maryland: Paulh Brookes Publishing Company. |

|

|

Yaman A (2017). Kayna?t?rma Modeli ile E?itilen Ö?renciler ?çin Bireyselle?tirilmi? E?itim Programlar?n?n Geli?tirilmesi ve Uygulanmas?na Yönelik S?n?f Ö?retmenlerinin Görü?lerinin Belirlenmesi [Determining the problems and possible solutions in the process of preparing and applying Individualized Education Plan for teachers who work in public schools which have inclusive application]. Necmettin Erbakan Üniversitesi, Konya. |

|

|

Yaz?c?o?lu T (2019). Rehberlik ö?retmenlerinin bireyselle?tirilmi? e?itim program? (BEP) biriminin i?leyi?ine ili?kin görü?leri. [The opinions of guidance teachers about functioning of unit of individaulized programme] Anemon Mu? Alparslan Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi Anemon Mu? Alpaslan University Journal of Social Science 7(5):225-234. |

|

|

Y?lmaz E, Batu ES (2016). Farkl? bran?tan ilkokul ö?retmenlerinin bireyselle?tirilmi? e?itim program?, yasal düzenlemeler ve kayna?t?rma uygulamalar? hakk?ndaki görü?leri [Opinions of primary school teachers about individualized education programme, legal regulation and inclusion implementation]. Ankara Üniversitesi E?itim Bilimleri Fakültesi Özel E?itim Dergisi Ankara University Faculty of Educational Sciences Journal of Special Education 17(3):247-268. |

|

|

Y?lmaz MF (2013). Bireyselle?tirilmi? e?itim programlar?n?n (BEP) uygulanmas?nda ilkö?retim kurumlar?nda görev yapan yöneticilerin kar??la?t?klar? engellerin incelenmesi [Investigation of the challenges primary school adninistrators face in the apllication of individulaized education programmes]. Hasan Kalyoncu Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü [Hasan Kalyoncu University Social Science Institute], Gaziantep. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0